CIAO DATE: 11/01

Combating Terrorism: Comments on H.R. 525 to Create a President's Council on Domestic Terrorism Preparedness

Statement of Raymond J. Decker

Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

United States General Accounting Office

May 9, 2001

Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Economic Development, Public Buildings, and Emergency Management, Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, House of Representatives

Mr. Chairman and Members of the Subcommittee:

We are pleased to be here to discuss a bill introduced by Representative Gilchrest of the full committee—the Preparedness Against Domestic Terrorism Act of 2001 (H.R. 525). The bill would create a new President's Council on Domestic Terrorism Preparedness to coordinate and increase the effectiveness of federal efforts to assist state and local emergency response personnel in preparation for domestic terrorist attacks.

We view this hearing as a positive step in the ongoing debate about the overall leadership and management of programs to combat terrorism and the nation's effort to reach consensus on the best approach. As you know, there are several other proposals to improve overall management of programs to combat domestic terrorism. While H.R. 525 proposes several changes to the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act,1 our comments, as agreed with your staff, are limited to a discussion of subtitle C that creates the new council. Many of the issues we raise should be familiar to the subcommittee because of our recent testimony before you on H.R. 525 and related bills and proposals. 2

Summary

We agree with the basic purpose of H.R. 525 to improve federal assistance to state and local personnel in preparing for and responding to domestic terrorist attacks. We also agree in principle with major actions required by the bill. Based upon the problems we have identified during five years of GAO evaluations, these major actions include the need to (1) create a single high-level federal focal point for policy and coordination, (2) develop a comprehensive threat and risk assessment, (3) develop a national strategy with a defined outcome to measure progress against, (4) analyze and prioritize governmentwide budgets to identify gaps and reduce duplication of effort, and (5) coordinate implementation among the different federal agencies. There are other proposals similar to H.R. 525 that would create a single focal point for terrorism. Some of these proposals place the focal point in the Executive Office of the President (like H.R. 525) and others place it in a Lead Executive Agency. Both locations have potential advantages and disadvantages.

H.R. 525 Would Address Key Actions Needed to Combat Terrorism

To improve federal efforts to assist state and local personnel in preparing for domestic terrorist attacks, H.R. 525 would create a single focal point for policy and coordination—the President's Council on Domestic Terrorism Preparedness—within the Executive Office of the President. The new council would include the President, several cabinet secretaries, and other selected high-level officials. An Executive Director with a staff would collaborate with executive agencies to assess threats; develop a national strategy; analyze and prioritize governmentwide budgets; and provide oversight of implementation among the different federal agencies.

In principle, the creation of the new council and its specific duties appear to implement key actions needed to combat terrorism that we have identified in previous reviews.3 Following is a discussion of those actions, executive branch attempts to implement them, and how H.R. 525 would address them.

H.R. 525 Would Create Single Focal Point in New Council

In our May 2000 testimony, we reported that overall federal efforts to combat terrorism were fragmented.4 There are at least two top officials responsible for combating terrorism and both of them have other significant duties. To provide a focal point, the President appointed a National Coordinator for Security, Infrastructure Protection and Counterterrorism at the National Security Council.5 This position, however, has significant duties indirectly related to terrorism, including infrastructure protection and continuity of government operations. Notwithstanding the creation of this National Coordinator, it was the Attorney General who led interagency efforts to develop a national strategy.

H.R. 525 would set up a single, high-level focal point in the President's Council on Domestic Terrorism Preparedness. In addition, H.R. 525 would require that the new council's executive chairman—who would represent the President as chairman—be appointed with the advice and consent of the Senate. This last requirement would provide Congress with greater influence and raise the visibility of the office.

H.R. 525 Would Require Threat and Risk Assessment

We testified in July 2000 that one step in developing sound programs to combat terrorism is to conduct a threat and risk assessment that can be used to develop a strategy and guide resource investments. 6 Based upon our recommendation, the executive branch has made progress in implementing our recommendations that threat and risk assessments be done to improve federal efforts to combat terrorism. However, we remain concerned that such assessments are not being coordinated across the federal government.

H.R. 525 would require a threat, risk, and capability assessment that examines critical infrastructure vulnerabilities, evaluates federal and applicable state laws used to combat terrorist attacks, and evaluates available technology and practices for protecting critical infrastructure against terrorist attacks. This assessment would form the basis for the domestic terrorism preparedness plan and annual implementation strategy.

H.R. 525 Would Require Council to Develop National Plan

In our July 2000 testimony, we also noted that there is no comprehensive national strategy that could be used to measure progress. The Attorney General's Five-Year Plan represents a substantial interagency effort to develop a federal strategy, but it lacks desired outcomes. 7 The Department of Justice believes that their current plan has measurable outcomes about specific agency actions. However, in our view, the plan needs to go beyond this to define an end state. As we have previously testified, the national strategy should incorporate the chief tenets of the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 (P.L. 130-62). The Results Act holds federal agencies accountable for achieving program results and requires federal agencies to clarify their missions, set program goals, and measure performance toward achieving these goals.

H.R. 525 would require the new council to publish a domestic terrorism preparedness plan with objectives and priorities, an implementation plan, a description of roles of federal, state and local activities, and a defined end state with measurable standards for preparedness.

New Council Would Analyze and Review Budgets

In our December 1997 report, we reported that there was no mechanism to centrally manage funding requirements and to ensure an efficient, focused governmentwide approach to combat terrorism. 8 Our work led to legislation that required the Office of Management and Budget to provide annual reports on governmentwide spending to combat terrorism. 9 These reports represent a significant step toward improved management by providing strategic oversight of the magnitude and direction of spending for these programs. Yet we have not seen evidence that these reports have established priorities or identified duplication of effort as the Congress intended.

H.R. 525 would require the new council to develop and make budget recommendations for federal agencies and the Office of Management and Budget. The Office of Management and Budget would have to provide an explanation in cases where the new council's recommendations were not followed. The new council would also identify and eliminate duplication, fragmentation, and overlap in federal preparedness programs.

New Council Would Coordinate Implementation

In our April 2000 testimony, we observed that federal programs addressing terrorism appear in many cases to be overlapping and uncoordinated. 10 To improve coordination, the executive branch has created organizations like the National Domestic Preparedness Office and various interagency working groups. In addition, the annual updates to the Attorney General's Five-Year Plan track individual agencies' accomplishments. Nevertheless, we have still noted that the multitude of similar federal programs have led to confusion among the state and local first responders they are meant to serve.

H.R. 525 would require the new council to coordinate and oversee the implementation of related programs by federal agencies in accordance with the domestic terrorism preparedness plan. The new council would also make recommendations to the heads of federal agencies regarding their programs. Furthermore, the new council would provide written notification to any department that it believes is not in compliance with its responsibilities under the plan.

H.R. 525 Is One of Several Proposals to Provide a Single Focal Point

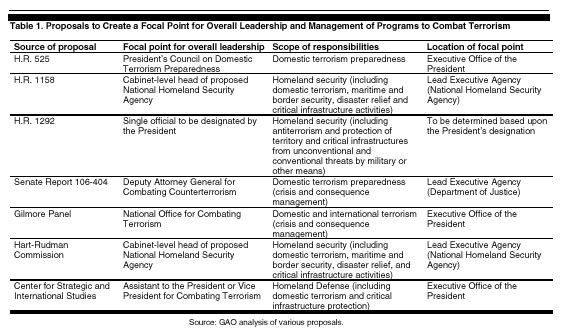

Federal efforts to combat terrorism are inherently difficult to lead and manage because the policy, strategy, programs, and activities to combat terrorism cut across more than 40 agencies. Congress has been concerned with the management of these programs and, in addition to H.R. 525, two other bills have been introduced to change the overall leadership and management of programs to combat terrorism. On March 21, 2001, Representative Thornberry introduced H.R. 1158, the National Homeland Security Act, which advocates the creation of a cabinet-level head within the proposed National Homeland Security Agency to lead homeland security activities. On March 29, 2001 Representative Skelton introduced H.R. 1292, the Homeland Security Strategy Act of 2001, which calls for the development of a homeland security strategy developed by a single official designated by the President.

In addition, several other proposals from congressional committee reports and various commission reports advocate changes in the structure and management of federal efforts to combat terrorism. These include Senate Report 106-404 to Accompany H.R. 4690 on the Departments of Commerce, Justice, and State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies Appropriation Bill 2001, submitted by Senator Gregg on September 8, 2000; the report by the Gilmore Panel (the Advisory Panel to Assess Domestic Response Capabilities for Terrorism Involving Weapons of Mass Destruction, chaired by Governor James S. Gilmore III) dated December 15, 2000; the report of the Hart-Rudman Commission (the U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century, chaired by Senators Gary Hart and Warren B. Rudman) dated January 31, 2001;11 and a report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (Executive Summary of Four CSIS Working Group Reports on Homeland Defense, chaired by Messrs. Frank Cilluffo, Joseph Collins, Arnaud de Borchgrave, Daniel Goure, and Michael Horowitz) dated 2000.12

The bills and related proposals vary in the scope of their coverage. H.R. 525 focuses on federal programs to prepare state and local governments for dealing with domestic terrorist attacks. Other bills and proposals include the larger issue of homeland security that includes threats other than terrorism, such as military attacks.

H.R. 525 would attempt to resolve cross-agency leadership problems by creating a single focal point within the Executive Office of the President. The other related bills and proposals would also create a single focal point for programs to combat terrorism, and some would have the focal point perform many of the same functions. For example, some of the proposals would have the focal point lead efforts to develop a national strategy. The proposals (with one exception) would have the focal point appointed with the advice and consent of the Senate. However, the various bills and proposals differ in where they would locate the focal point for overall leadership and management. The two proposed locations for the focal point are in the Executive Office of the President (like H.R. 525) or in a Lead Executive Agency.

Table 1 shows various proposals regarding the focal point for overall leadership, the scope of its activities, and it's location.

Based upon our analysis of legislative proposals, various commission reports, and our ongoing discussions with agency officials, each of the two locations for the focal point—the Executive Office of the President or a Lead Executive Agency—has its potential advantages and disadvantages. An important advantage of placing the position with the Executive Office of the President is that the focal point would be positioned to rise above the particular interests of any one federal agency. Another advantage is that the focal point would be located close to the President to resolve cross agency disagreements. A disadvantage of such a focal point would be the potential to interfere with operations conducted by the respective executive agencies. Another potential disadvantage is that the focal point might hinder direct communications between the President and the cabinet officers in charge of the respective executive agencies.

Alternately, a focal point with a Lead Executive Agency could have the advantage of providing a clear and streamlined chain of command within an agency in matters of policy and operations. Under this arrangement, we believe that the Lead Executive Agency would have to be one with a dominant role in both policy and operations related to combating terrorism. Specific proposals have suggested that this agency could be either the Department of Justice (per Senate Report 106-404) or an enhanced Federal Emergency Management Agency (per H.R. 1158 and its proposed National Homeland Security Agency). Another potential advantage is that the cabinet officer of the Lead Executive Agency might have better access to the President than a mid-level focal point with the Executive Office of the President. A disadvantage of the Lead Executive Agency approach is that the focal point—which would report to the cabinet head of the Lead Executive Agency—would lack autonomy. Further, a Lead Executive Agency would have other major missions and duties that might distract the focal point from combating terrorism. Also, other agencies may view the focal point's decisions and actions as parochial rather than in the collective best interest.

Passage of H.R. 525 May Warrant Changes in Existing Organizations

H.R. 525 would provide the new President's Council on Domestic Terrorism Preparedness with a variety of duties. In conducting these duties, the new council would, to the extent practicable, rely on existing documents, interagency bodies, and existing governmental entities. Nevertheless, the passage of H.R. 525 would warrant a review of several existing organizations to compare their duties with the new council's responsibilities. In some cases, those existing organizations may no longer be required or would have to conduct their activities under the supervision of the new council. For example, the National Domestic Preparedness Office was created to be a focal point for state and local governments and has a state and local advisory group. The new council has similar duties that may eliminate the need for the National Domestic Preparedness Office. As another example, we believe the overall coordinating role of the new council may require adjustments to the coordinating roles played by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Department of Justice's Office of State and Local Domestic Preparedness Support, and the National Security Council's Weapons of Mass Destruction Preparedness Group in the policy coordinating committee on Counterterrorism and National Preparedness.

Conclusion

In our ongoing work, we have found that there is no consensus—either in Congress, the Executive Branch, the various commissions, or the organizations representing first responders—as to whether the focal point should be in the Executive Office of the President or a Lead Executive Agency. Developing such a consensus on the focal point for overall leadership and management, determining its location, and providing it with legitimacy and authority through legislation, is an important task that lies ahead. We believe that this hearing and the debate that it engenders, will help to reach that consensus.

This concludes our testimony. We would be pleased to answer any questions you may have.

GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgment

For future questions about this statement, please contact Raymond J. Decker, Director, Defense Capabilities and Management at (202) 512-6020. Individuals making key contributions to this statement include Stephen L. Caldwell and Krislin Nalwalk.

Notes:

Note 1: 42 USC section 5121 et. seq. Back.