|

|

|

|

|

|

CIAO DATE: 11/00

The Imposition of Governance: Transforming Foreign Policy through EU Enlargement

Thomas Diez

August 2000

1. The South-Eastern Puzzle

Driving me through Ankara only a couple of hours after I disembarked the plane, my Turkish colleague points to the latest apartment buildings and a hypermodern shopping mall further down the road. These places, he points out, would be ready for the EU. If only all of Turkey would already look like them - but eventually, it will. Only give us some time. And indeed, the economic change over the past decade seems remarkable. Then Prime Minister Turgut Özal's final abandonment of statism, one of the six pillars of Kemalism, in favour of a widespread, although still restricted, liberalisation strategy, looks like bearing visible fruits. Despite the Turkish economy nonetheless still experiencing a great deal of difficulties (inflation in 1999 was still above 60%, and that already was a huge improvement on previous years), my conversations in the following week centre on a different issue - Turkey's foreign policy. With its 40,000 soldiers in northern Cyprus, its continually problematic relationship with Greece, its ventures into northern Iraq and threatenings towards Syria, Turkey's foreign policy is, together with human rights issues, one of the central stumbling blocs for starting membership negotiations after the acknowledgement of candidate status in Helsinki. In Cyprus's southern part, the economic problem of the day is its overheated stockmarket. My friend multiplied his assets within half a year. More and more villas are mushrooming in beautiful settings, and the younger generation in particular is very well off. Accordingly, Cyprus is the forerunner in the enlargement negotiations, with a GNP per capita above some of the current EU member states (Pace 2000: 122). No wonder then that my conversation again focus on what most Cypriot politicians regard a domestic issue, but which at least has a strong foreign policy aspect to it: its policy towards the northern part of the island, 'under Turkish occupation' as the official labelling goes, and thereby also to Turkey. Despite Cyprus's status in the negotiations, its probable future membership is thus overshadowed by the conflict on the island.

Both Turkey and Cyprus do not figure prominently in the literature on the current enlargement round. Although there are some studies dealing with them individually, or addressing the next round of Southern enlargement, there is hardly any theoretically informed analysis situating these two membership candidates within the larger context of the current negotiations. Comparing Turkey and Cyprus to the other membership candidates may, however, yield some insights into the conditions under which state identities change as an effect of first the enlargement process and then membership. In this paper, I cannot perform such a comparison. Instead, my aim is to clear some conceptual ground, using Turkey and Cyprus as my illustrative examples. My basic argument is as follows:

The imposition of governance through enlargement should include not only domestic changes, but also foreign policy behaviour. This is of practical relevance since the EU has been seen as an important part of the Western European 'peace community', which would be severely challenged if member states did not conform to basic foreign policy norms. Although rational actors dominate the enlargement process, securing the outcome of enlargement depends on effective socialisation, understood as a transformation of state identities, rather than a stable equilibrium of interests. Such a transformation, in turn, depends on a number of conditions at least some of which fall in the realm of discourse. These discourses are easier to change if there is already a trace of divergent behaviour on which new practices can build. Such a trace may be implanted in the negotiation period, or needs to come from outside the enlargement process.

My argument runs counter to the widespread characterisation in both the academic literature and the public debate that the EU can impose its system of governance on the membership candidates because of a strong power asymmetry in the negotiation process based on both material and ideological superiority of the West (Schimmelfennig 2000b: 124). The Southeastern candidates direct our attention to possible differences both between countries and between policy areas. The basic question, however, could also be investigated through different comparisons: (a) through historical comparison with earlier enlargements, and in particular Greece; (b) through interorganisational comparison with NATO, and in particular its influence on Greek-Turkish relations. Recently growing resistance to membership within some Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs) such as Poland indicates that there are differences within and between the CEECs, too. Furthermore, as David Allen (1998: 110-6, 123) suggests, the CEECs, and in particular those with an infant foreign policy machinery, may be more willing to subscribe to CFSP than some of the large member states, but they also have their own security agenda that often sits uneasily with current EU objectives.

My choice of Turkey and Cyprus is pragmatic more than anything else: It reflects my previous research interest, and that I became interested in the question at hand through this previous research. The option of a comparison with NATO suggests, though, that my argument may be of wider relevance for the theory of international organisation, where the issue of the relevance of socialisation processes is still high on the agenda (see e.g. Paul and Hall 1999).

The paper is divided into four parts. The next section will establish foreign policy behaviour as a part of supranational governance. This is followed by a short review of the EU's relation with Cyprus and Turkey, and their foreign policies. The central argument is then presented in section four. It distinguishes a rationalist and two constructivist propositions about the imposition of governance as an effect of membership negotiations and membership itself. I will argue that these different paths of transformation are related, but that for the transformation to be stable in the long term, the constructivist variable of state identity is crucial, leading to a change of the mode in which foreign policy is conducted. The conclusion will then play out various scenarios for the cases of future Cypriot and Turkish membership, and reflect on the theoretical implications of the argument.

2. Foreign Policy Behaviour and Governance

2.1. A sociological understanding of governance

Not too long ago, the term governance was hardly used in International Relations literature. Today, it is omnipresent, and accordingly, its usage differs widely and is often theoretically unreflected. For the context of this paper, it is useful to distinguish two basic understandings of governance:

A first, organisational one sets governance apart from government. Whereas the latter implies a more or less hierarchical and centralised political rule of a clearly demarcated society, and is therefore tied to the modern territorial state, governance stands for modes of political organisation in which decision-making processes leading to results that are binding for all members do not presuppose such an hierarchical structure. The traditional realist argument, tied to the modern state, is that order in international relations is always problematic, because it would otherwise have to rest on a sort of world government, which is an unlikely and maybe also unwanted event. Therefore, government is confined to the domestic space of states, whereas the international system is seen as anarchical by definition. Against this, the governance literature starting to spread from the second half of the 1980s has argued that world government is not a necessary condition for effective and binding decision-making in the international realm. Instead, there could be 'governance without government' (Rosenau and Czempiel 1992). As such, this literature can be seen as an offshoot of the literature on international regimes showing that through 'sets of implicit or explicit principles, norms, rules and decision-making procedures' (Krasner 1983: 2), international co-operation is possible even in the absence of an hegemon imposing such co-operation (e.g. Krasner 1983; Keohane 1984; Kohler-Koch 1989; Hasenclever, Mayer and Rittberger 1999). This governance terminology has also gained prominence in the 'governance school' literature on European integration, where the EU has been analysed as a distinctive system of governance that is not a classical modern state, nor will it necessarily and in the foreseeable future develop into one (Kohler-Koch and Eising 1999; Jachtenfuchs and Kohler-Koch 1996; see also Diez 2001; and Friis and Murphy 1998 for a similar distinction between 'soft' and 'hard' governance).

Whereas this organisational distinction between government and governance is a rather simple one, the second, sociological understanding of governance is more complex. Here, governance is seen as a structure that 'governs' individuals by making them conceptualise the world in specific ways and regard certain forms of action appropriate. Such a definition is actually not too far from the above definition of regimes as sets of principles, norms, rules and procedures, but emphasises the structural quality of these 'sets'. There are two major sources of such an understanding of governance. The first one is Michel Foucault's concept of governmentality, a particular modern 'mentality' to govern through a decentralised web of regulation techniques (Foucault 1991). Nikolas Rose and Peter Miller build on this concept when they define government as 'the historically constituted matrix within which are articulated all those dreams, schemes, strategies and manoeuvres of authorities that seek to shape the beliefs and conduct of others in desired directions' (Rose and Miller 1992: 175). According to this definition, authorities 'govern' citizens, while they are at the same time themselves bound up with a 'governing' matrix. To distinguish this matrix from the authorities themselves, 'governance' seems to be the more appropriate term than 'government' used by Rose and Miller. A second source for the sociological understanding can be found in systems theory. Jan Kooiman (1993: 258) conceptualises governance as the systemic structure that evolves from the actions of socio-political agents. From such a perspective, governance can be seen as a system within society that follows its own specific codes, which are simultaneously enabling and being reproduced through agency. Both Kooiman and Rose and Miller thus see governance not as a term for a different type of organisation but as a structure that governs the behaviour of those embedded in it in the socio-political realm.

From a traditional perspective in which the domestic is clearly demarcated from the international sphere, foreign policy is performed by governments, but has nothing to do with governance. In most European integration literature, the discussion of foreign policy is therefore separate from analyses of governance. If we allow for the possibility of transnational governance without a government, however, foreign policy may at least be crucially linked to governance. Furthermore, from a sociological perspective, foreign policy is part of the socio-political system, and foreign policy behaviour should thus be seen as being embedded in a system of governance, which is not bound by national borders. Research on security communities suggests, for instance, that in pluralistic but 'tightly coupled' security communities, 'authority and legitimacy' are dependent on the 'normative structure' of the community, and 'states come to defend a regional point of view' rather than their own (Adler 1997: 266-7).

This linking of foreign policy to a sociological understanding of governance ties in nicely with the puzzle set out in the introduction. NATO as a security community, for instance, could be seen as providing a system of governance for the foreign policy behaviour of its members. The question would then be how successful this system of governance is. In other words, we would have to assess the capability of that system 'to govern itself' (Kooiman 1993: 259). For the more specific question of EU enlargement to be tackled here, enlargement may be defined as a process of 'gradual and formal horizontal institutionalisation', where 'institutionalisation' is defined as 'the process by which the actions and interactions of social actors come to be structured and patterned by norms and rules' (Schimmelfennig 2000a: 3). EU Enlargement thus involves both the extension of institutions of supranational governance to new member states (organisational) and the socialisation of new member states into a governance structure guiding their behaviour (sociological). This includes their foreign policies, and it does so to an increasingly important extent, as was in fact implicitly recognised by the member states in their linking of enlargement to a European security order (Friis and Murphy 1999: 220-1).

2.2. Two norms of European foreign policy

In contrast to the view from an intergovernmentalist perspective, foreign policy has for long been seen as part of the integration process, and thereby, according to the above logic, of the evolving system of European governance, by social constructivist and neofunctionalist approaches. These have stressed three transformation processes. For one, a change in the self-construction of the diplomats tied to the EPC/CFSP system towards a community we-feeling. Second, the development of a 'coordination reflex' that makes unilateral foreign policy declarations the exception from the rule. Third, an increasing number of previous common declarations and stances, amounting to an 'acquis politique' (Ginsberg 1999: 444; Glarbo 1999; Jørgensen 1997; Øhrgaard 1997). In such a perspective, we therefore witness a process of political integration far beyond the realm of economic and social policy (Øhrgaard 1997). A crucial ingredient of integration, however, is a process of (international) socialisation (ibid.: 3), which in turn is 'directed toward a state's internalisation of the constitutive beliefs and practices institutionalised in its international environment' (Schimmelfennig 2000b: 112). Foreign policy becomes part of a European system of governance.

Recent developments indicate that foreign policy will in the future play an even more important and more obvious role in this system of governance. While CFSP was only very cautiously inserted in the Maastricht Treaty, the Treaty of Amsterdam reformed and consolidated the CFSP structure, adding to it the dimension of a European Strategic and Defence Identity (ESDI). With the crises in former Yugoslavia as a catalyst, though, the developments beyond the formal treaty revisions seem to be even more important, having led by now to the Helsinki decision to install a rapid deployment force for the intervention in humanitarian crises.

If foreign policy is thus an increasingly important part, or in fact subsystem, of the European system of governance, what are the central rules and norms that make it work? I propose two, one organisational, the other one relating to the content of foreign policy.

The organisational norm has already been mentioned: co-ordination. As opposed to a classical intergovernmental system, European foreign policy is not built around the norm of preserving autonomy, counterexamples notwithstanding. A widely quoted counterexample might illustrate the point: Germany's early recognition of Croatia and Slovenia in early 1992. Situated in a larger context, this example rather shows the workings of the co-ordination norm as the rule. On the one hand, the move was contested and widely criticised within Germany itself with reference to the co-ordination norm, and the German government on later occasions refrained from repeating its unilateralism (Banchoff 1999). On the other hand, this incidence was not used by the other member states to follow suit with further unilateral actions. Instead, they, too, criticised the German government's behaviour by reference to the co-operation norm, while sticking to it themselves.

The content norm refers to the aims of foreign policy, and I propose that desecuritisation in the classical field of political and military security is central here. Following the terminology of Ole Wæver, securitisation is a speech act that represents an issue as an existential threat for a referent object, 'requiring emergency measures and justifying actions outside the normal bonds of political procedure' (Buzan et al. 1998: 23-24). Desecuritisation, accordingly, is aimed at bringing a securitised issue back into the realm of 'normal politics' (Wæver 1995). The Cold War was a typical situation in which securitisation was central to the foreign policies of states in both East and West. Oversimplified, the other side was threatening to destroy 'us' and 'our' system, therefore it was crucial to keep or improve nuclear arsenals, and those who dispute this are traitors.

Similarly, Europe before 1945 was characterised by securitisations as the norm of foreign policy. Since then, though, the picture has changed. EU-internal relations have become a classic case of desecuritisation, establishing Europe as a 'peace community' in which contemporary issues are normally not phrased in security terms - a situation of 'asecurity' (Rasmussen 1998; Wæver 1998). The first and foremost threat articulated in securitisations within the EU is Europe's own past (Wæver 1998: 90; Buzan et al. 1998: 187). But does this hold for Europe's relations with its external environment, too?

The answer is, I propose, a qualified Yes. Traditionally, the EC/EU has been regarded as a 'civilian' rather than a military superpower, and gained part of its recognition as an international actor by being identified with 'peace and reconciliation' (Feldman 1999: 84; see Duchéne 1972; Ginsberg 1999: 445; Hill 1990; Whitman 1998; but see Bull 1982 for an assessment to the contrary). Advocates of European integration during the Cold War have repeatedly called for Europe to become a third force in the international system, mediating between the superpowers. One of the first successful acts of EPC was to bring CSCE on its way (Urwin 1995: 149). Even the response to the Yugoslavian crisis can be interpreted as a result of such a conceptualisation as civilian power. It is telling that one thing the EU stands for is the governing of Mostar as a multicultural town, even though this has not been very successful. The latest developments may change this characterisation to the extent that a 'civilian power' is conceptualised as an internationally influential actor lacking a military dimension (Twichett 1976: 8 quoted in Ginsberg 1999: 445). But even then it would be remarkable that the EU would be the only superpower that constitutionally binds her military involvement to international organisations, and in particular the United Nations (Art. 11 TEU).

This is not to say that the EU is not engaged in securitisations in other sectors of international relations, such as in the fields of economics ('trade war') and societal security ('immigration threat'). But in the 'classic' foreign policy fields of political and military security, her constitutive norm seems to be desecuritisation. Neither is this to say that European actors are not, and sometimes heavily, involved in military conflicts through the sale of arms, the provision of other military means, or mercenary armies. But in all of these cases, the involvement is not through an active foreign policy by securitisation.

As far as the individual member states' foreign policies are concerned, a number of counterexamples may come to mind: Britain's Falkland war, or France's repeated military engagement in its former colonies. But note the opposition of the other member states to such involvement. Furthermore, all of these incidences were connected to historical legacies, and were not directed at states territorially adjacent. The exception is Greece's rivalry with Turkey, which repeatedly brought the two countries to the brink of war, again being condemned by the other EU members. These examples, though, show that the system of governance in foreign policy is precarious. Although the desecuritisation norm rules the foreign policy behaviour of member states to a large extent, there are a number of critical exceptions indicating that integration in this field is less than perfect.

If the argument in this section is accepted, the discussion about the imposition of governance cannot exclude an assessment of the likely effects of enlargement on the foreign policy behaviour of prospective member states. Given the growing importance of the foreign and security pillar within the EU structure, the membership candidates need to be brought into the EU's system of foreign policy governance in order to avoid future conflicts within, or being drawn into conflicts outside EU territory. The Greek example may serve as a warning in this respect. Taken up as a member primarily out of political considerations, Greece later proved to be a particularly difficult partner not only in its behaviour towards Turkey, but also in other foreign policy areas such as the recognition of Macedonia (Allen 1998: 112). The chapter on CFSP within the membership negotiations is thus as important as those chapters relating to EC matters. And it is here where the cases of Cyprus and Turkey are, or may become problematic.

3. EU Enlargement and Cypriot and Turkish Foreign Policy

3.1. Cyprus

As stated above, Cyprus has in many ways been an 'ideal' applicant. In contrast to the CEEC's, its economy had not just recently been transformed when the negotiations started, and the Association Agreement of 1972 and an accompanying Protocol of 1987 towards a Customs Union had already prepared the country for the implementation of the acquis communautaire. Of the fifteen chapters originally opened in the negotiations, ten could provisionally be closed by the end of 1999, i.e. Cyprus is regarded 'fit' for membership in these matters. The five open chapters are Fisheries, Company Law, Competition Policy, Free Movement of Goods - and CFSP.

As far as CFSP is concerned, the picture is ambiguous. On the one hand, and despite the domestic opposition against the intervention in Kosovo and some doubts about Cyprus following the embargo of Yugoslavia, the Commission's progress report concludes that the country 'has regularly aligned itself with the Union's statements, declarations and démarches, including in the context of the UN and OSCE'. It also stresses that Cyprus 'strives to contribute to regional stability in the framework of the Euro-Mediterranean dialogue' (European Commission 1999a: 3.8). One official in Brussels could thus not understand why some of the member states blocked the provisional closing of the CFSP chapter. In principle, he argued, the Cyprus problem is as much relevant to any other chapter as it is to CFSP (personal interview, Brussels, April 1999; interviewee does not wish to be identified).

This may be true, but on the other hand foreign policy is an issue that has been and still is dominated by the conflict on, and about the island. Most of the energy in Cypriot foreign policy has been spent on internationalising the conflict, and thereby gaining support in the international community. Even membership, in the absence of clear indications of economic benefit, has been promoted as a political tool in that it would have a 'catalytic effect' towards conflict resolution (Diez 2000).

Thus, even though the Commission's Progress Report evaluates Cypriot foreign policy positively, it is nonetheless dominated by one particular issue in which the securitisation of Turkey and 'the North' as an essential threat to the existence of the Cypriot state plays a central role. The identity of the current Republic of Cyprus is very much built on this securitisation, as is visible in the place it is given in nearly any publication, or in the hindrances for alternative forces to engage in intercommunal contacts (Constantinou and Papadakis 1999).

3.2. Turkey

Regarding Turkey's foreign policy as problematic for European governance is at odds with the prevailing view that the country's EU membership is would be beneficial for strategic reasons. But such argumentation is shortsighted.

Turkey is a unique case in the sense that it is a member of NATO and has the oldest Association Agreement with the EU, which already in 1963 opened up the conditional perspective of membership. But, although eventually given candidate status in Helsinki in December 1999, the country is as yet still far from even the opening of formal membership negotiations. The history of this process is well known (see e.g. Müftüler-Bac 1997), and so are the basic hindrances, of which a regionally uneven economy and extraordinarily high inflation are perceived as only minor ones. More central to the current discussion is Turkey's human rights record, its treatment of the Kurdish issue, and the influence of the military on domestic politics through the National Security Council.

Some of these hard issues are directly linked to foreign policy (Jung and Piccoli 2000: 93). The Kurdish issue, for instance, continues to spill over into the power vacuum of Northern Iraq, where Turkish forces have been persecuting PKK-activists. Similarly, it is one of the issues of conflict with Syria, which brought the countries to the brink of war in late 1998. The military has a strong say in all aspects of foreign policy, as is illustrated by the Chief of Staff being higher in protocol than the Minister of Defence. It is omnipresent as a 'peace force' in Northern Cyprus - and to guard Turkey's 'southern flank'. Even its role as the 'guardian of the constitution' has foreign policy aspects. Part of the core of Turkish constitutionalism, the principles of Kemalism, is secularism and republicanism. Both are tied to a long-standing attempt to 'Westernise' the country from the Ottoman Empire to a modern secular republic as part of the European system.

But what is understood here as the European system is more reminiscent of a concert of powers than an integration process. In the mind of many Turkish politicians, Turkey has a right to be part of Europe because it defended Europe for more than 40 years against the Communist threat (Andersen 2000). 'To be part of Europe' often seems to be of utmost political symbolism, but there seems to be little preparedness to let others have a say in Turkish affairs (Jung and Piccoli 2000: 102). In a recent survey of Turkish elite attitudes to European integration, the focus was on economic benefits, with the political effects of membership grossly underplayed (McLaren 2000). In other words, the perspective of becoming part of a supranational system of governance seems as yet far out, while securitisations are deeply interwoven with its foreign policy, and the 'West' is conceptualised mostly in military-strategic terms (Buzan and Diez 1999).

Central to Turkish foreign policy is the sense of living in a 'tough neighbourhood' (Olgun 1999). The following extract from a contribution to an internet discussion list on Cyprus may only be the private statement from a private person, but it matches the official rhetoric quite well: 'Turkey is not surrounded by the peaceful water of Mediterranean sea. We are a neighbour of Iran, which is trying to export his regime and has already involved with the massacre of many valuable journalists in Turkey since they are secularists! Also we have to live right next to Iraq whose leader's craziness is a fact known by the whole world.' (Cyprus Forum, 25 May 00, www.cyprusforum.com). This construction of the region is typical of what Dietrich Jung and Wolfango Piccoli (2000: 93) have called the 'Sèvres syndrome' of Turkish politicians: The constant 'sense of encirclement' and of an 'international conspiracy to weaken and divide Turkey'.

True, Turkey has traditionally followed a cautious approach in the Middle East. But the ventures into Iraq, the alliance with Israel, and the general foreign policy rhetoric suggest that this Sèvres syndrome is nonetheless a crucial pillar of Turkish foreign policy behaviour. Similarly, Turkey engages in a number of foreign policy activities that may fall under the label of desecuritisation, ideologically underpinned by the Kemalist 'peace at home, peace abroad' principle (Kazan 2001). As such, Turkey has been very active in founding and promoting the Black Sea Economic Cooperation Council (BSECC), it has tried to build regional links between the Turkic countries of Central Asia, and more lately in the Caucasus, and it has proposed to provide its water resources to further peace in the Middle East (Müftüler-Bac 1997: 42-46). But just like its military partnership with Israel, these initiatives may be seen as falling within the realm of traditional foreign policy to advance national interests.

The Commission's progress report on Turkey consequentially is more sceptical than towards Cyprus. It notes, for instance, the 'strained relations' to Syria and Iraq, and the lack of progress on the Cyprus issue (European Commission 1999b: 3.3.). It also refers to the 1998 report and its conclusion that 'Turkey must make a constructive contribution to the settlement of all disputes with various neighbouring countries by peaceful means in accordance with international law' (ibid.: 1.).

As in the case of Cyprus, Turkish national security is predominantly constructed in military terms (Jung and Piccoli 2000: 102) and military and political securitisation plays a crucial role in Turkey's self-construction. From a systemic perspective, Turkey currently insulates two regional security complexes in the Middle East and Europe (Buzan and Wæver, 2001). Should it become a member of the European Union without a change in its foreign policy, the EU may well be drawn into the conflicts at Turkey's South-Eastern borders (Buzan and Diez 1999: 52). Of course, relations in the Middle East may well change, but that also in part depends on a change in Turkish foreign policy norms.

4. Conceptualising Enlargements

4.1. Imposing governance

In the enlargement literature, there is a broad consensus that the EU is in a unique position to impose its system of governance on the CEEC membership candidates. In some respects, the EU even seems to be able to enforce more strict criteria for candidates than for current members (Grabbe 1999: 6, 9). The puzzle most often posed is therefore not related to the applicants, but to why the EU would want enlargement (Schimmelfennig 2000a: 30). For the CEECs, it is assumed that there are overwhelming reasons to do whatever possible to become part of the EU: economic and political pull-factors to become part of a prosperous and stable, democratic zone of peace, and push factors related to history and identity - the effort to leave the 'Eastern' past behind and become part of the 'West', and therefore to distance oneself as far as possible from Russia, and indeed from one's Eastern neighbour (Neumann 1998).

Once in the negotiation process, though, the EU can dictate its conditions because of a strong power asymmetry between the EU and the candidates, so that the latter can only try to keep their adjustment costs as low as possible (Schimmelfennig 2000b: 123). In the process, the EU is able to export governance to the applicant states both in its organisational and in its sociological form, and often even before it issues formal requests (Friis and Murphy 1999: 220). This export involves formal agreements, the implementation of which is permanently screened, as well as an informal 'teaching' route through bureaucratic and private sector contacts and the EU's role as a model for the applicant states (Grabbe 1999: 10-14). As long as no final agreement is made, the EU at least in theory can threaten not to take up the respective applicant because of insufficient transformation.

This understanding of the enlargement process has, however, a bias to which I will have to return below. Apart from the efforts to keep transformation cost down, it relegates applicants to pure objects of EU enlargement policy. On a superficial level, this looks like a fair description of current events. The CEECs are forced to liberalise their markets, close down nuclear plants (Lithuania), or change their citizenship law (Latvia and Estonia). The resistances and conflicts surrounding the latter issue, though, are indications that just as member state governments, the applicants have their own agenda, and may as well interpret certain rules in their own way and use them for their own purposes. Both Cyprus and Turkey thus may, just as Greece, be staunch supporters for the further development of ESDI, but they may do so for their own, and indeed for reasons incompatible with those of other member states, not to speak between themselves.

The theoretical problem lurking behind this issue is that power-constellations are never one-way streets. The objectification of other actors is a common phenomenon in situations similar to the enlargement process, where one actor tries to impose a certain way of doing things onto another one - development is a classic case (Ferguson 1990). Hardly ever, though, do things work out the way they should, because in the end implementation processes can never be fully controlled, and policies are given a different meaning by actors 'on the ground' (Clarke and Smith 1989; in relation to EU enlargement: Grabbe 1999: 18). Indeed, it is now a commonplace to state that the EU after enlargement will not be the same as before, but this is often only related to the effects of size, i.e. in an organisational view (e.g. Ginsberg 1999: 446; see Allen 1998: 118). It may though well be that the EU system of governance is also transformed in the sociological sense of the term (for a similar argument, see Friis and Murphy 1999: 212).

This is why the study of the effects of enlargement is such a crucial undertaking. In the absence of a large number of cases, though, one is left more with theoretically informed speculation than with detailed studies, although the historical cases mentioned in the introduction may help to elucidate this issue further. Nonetheless, as I will show in the following, our theoretical tools already allow us to formulate some expectations about the processes and conditions of the imposition of governance.

4.2. A rationalist argument

The conventional view of enlargement is largely, if often only implicitly, based on the assumption of rationality of the actors involved. Frank Schimmelfennig (2000b), for instance, has convincingly shown that in the negotiation process, all actors in principle behave according to their own preference structure under the avoidance of high cost. This matches the liberal-intergovernmentalist theory of integration processes, which are essentially conceptualised as bargaining situations in which actors with a mandate as an outcome of domestic preference formation try to find an equilibrium of their preferences, consisting both of coinciding or complementary preferences and of package deals (Moravcsik 1998).

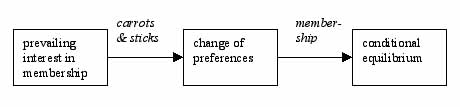

In this bargaining situation, governance can be imposed through a strategy of carrots and sticks if EU membership as such is the prime aim, although the only real 'stick' the EU holds in its hands is the denial of the carrot of membership. In other words, applicants, as the above examples have illustrated, can be forced to change their policies in areas that they regard as less important than membership itself if they are given enough incentives to do so. Alternatively, politically sensitive issues such as the four freedoms in the case of Cyprus may be approached as a purely technical matter, which, however, imply political changes (see Diez 2000). In this case, applicant countries may not be fully aware of the consequences of a seemingly technical decision, or they may eventually again weigh the negative consequences lighter than the positive ones. Thus, Cyprus agreed for instance to allow Turkish ships back into Cypriot harbours, and thus fulfilled the EU-Turkish Association Agreement, probably calculating that not many Turkish ships would make use of that option anyway. Additionally, applicant states may only superficially speak the 'supranational talk', while de facto continuing their 'national walk' (Grabbe 1999: 17 quoting Jacoby 1998: 12).

The outcome then is what I call a 'conditional equilibrium'. It is an equilibrium of preferences that holds as long as the actors' preferences do not change. It is thus conditional on the absence of change, for instance in the international system that would create a reassessment of preferences. In the realm of foreign policy, this outcome would be coinciding or complementary securitisations and desecuritisations. Thus, some member states may want to strengthen ESDI as a way to enhance the EU's political identity, legitimising their move with the securitisation of the past, while Greece, Cyprus and Turkey, for instance, may want to strengthen ESDI in order to achieve a strong commitment for territorial integrity, legitimising their move with the securitisation of their respective 'bad neighbours'.

The example illustrates the limits of such a rationalist approach. Although it seems to be able to explain the immediate change in foreign policy behaviour on the side of the applicant countries (but not necessarily of the Western institutions, see Schimmelfennig 2000a: 25) if such a change is necessary, it does not fundamentally alter foreign policy behaviour. In other words, the conditional equilibrium is an outcome of temporary coincidence or complementarity of securitisations, but not a general shift towards a new norm of desecuritisation in foreign policy. The enlargement outcome may thus be seen as unstable in the long run. Even those who argue for its stability, have to rest their argument on there being 'no incentive to deviate from the institutionalised norms' (Schimmelfennig 2000b: 119), which is the case as long as the international structure remains the same. To achieve, however, the 'reproduction of the liberal international order', such a rationalist argument has to bring in constructivist factors such as norms internalisation (ibid. 121). Worse, though, the conditional equilibrium is not a change of the system of governance sociologically speaking. Neither the norm of co-ordination nor the norm of desecuritisation is playing a role in these purely rationalist considerations.

Figure 1: A rationalist account of enlargement effects

4.3. Constructivist alternatives

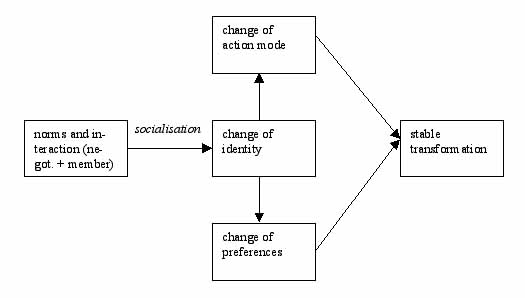

The constructivist critique of the rationalist model is twofold: It ultimately cannot explain how preferences are formed, but has to impute a specific logic from the outside; and it does not take into account that there are two different modes of action, following two different logics. In the conceptualisation of alternatives as answers to these criticisms, norms play a crucial role.

There is by now an extensive literature on the role of norms on state behaviour. In this literature, norms are conceptualised to have two possible effects. First, they affect the identity of actors. In the following, this identity is defined as the self-construction of political actors in relation to the country they seek or are supposed to represent. These actor identities are embedded in wider discourses of national identity, which they in turn reproduce. Norms transform the actors' preference structure if and to the extent to which they, as parts of the wider discourses in which actors are embedded, transform actor identities (Finnemore 1996: 5-7; Wendt 1999: 113-136). In this model, the basic assumption of rationality is not fundamentally questioned. The preference structure of actors, however, is itself problematised - it is 'endogenised' into the analysis.

The second influence of norms is more radical in that actors according to this model do not follow norms because of a change in their preference structure, but because in their actions they are guided not by a logic of consequentiality, but of appropriateness (March and Olsen 1989; Finnemore 1996: 29). In other words, their actions are not outcomes of cost/benefit calculations. Instead, actors do things in a specific way because this is the way things are done in their context. They accept the norm in question and therefore take it to be appropriate to follow it. This norm-acceptance implies that actors define their identity in ways that integrate the norm. In other words, for the logic of appropriateness to set in, identities need to change if they were previously at odds with the norm in question. There is an alternative possibility of superficial norm-following not based on considerations of appropriateness but rationality, which nonetheless leads to routinisation and a change of identity. This is, however, I contend, not a direct influence of norms in the constructivist tradition outlined here, but a discursive feedback effect from the rationalist conditional equilibrium to which I will turn below.

Figure 2: A constructivist account of enlargement effects

In both of these constructivist alternatives, the effect of enlargement, and to some extent already of sustained interaction during the enlargement process (Allen 1998: 115; Grabbe 1999: 17-18), would be that through socialisation, applicant states change their identity in terms of their self-construction. Typically, this would involve integrating 'Europe' in national identity articulations (Wæver 1998: 94), or identifying with the ideal of Europe as a force for peace. Such a transformation would shift foreign policy preferences towards, say, a stress on common European engagement in conflicts as an alternative to American omnipresence. Through such a transformation of preference structures, an equilibrium could possibly be built that focuses on desecuritisation rather than coinciding securitisations. In the second constructivist alternative, the effect of enlargement would be a proper 'imposition of governance' in that the norms of co-ordination and desecuritisation would, again through socialisation, replace cost/benefit considerations as the central motivation for foreign policy.

Both of these effects would be more stable than the conditional equilibrium effect in the rationalist scenario. Changes of identity and action mode can be seen as transformations of 'deeper' layers of human behaviour that cannot as easily be changed as preferences. These constructivist alternatives may thus account for a fundamental alteration of foreign policy behaviour as an effect of enlargement.

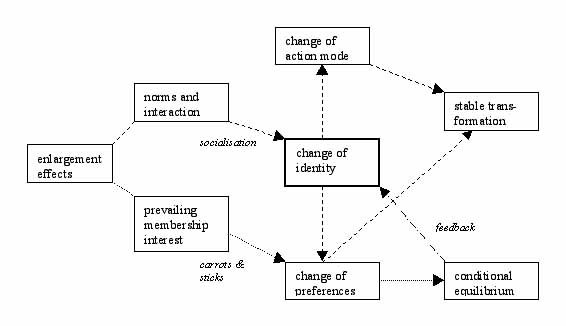

4.4. A combined model

The alternatives of enlargement effect on foreign policy behaviour of applicants or new member states reconstructed above are ideal types to clarify the three different logics underlying them. In practice, they are intertwined so that they may be combined into a general model (Figure 3).

Figure 3: A combined model of enlargement effects

As indicated above, the rationalist change of preferences through a carrot and stick strategy may result in feedback that contributes to a change of identity. A first feedback effect is predominantly actor-oriented. This is an effect that is best captured in the 'spiral model' within the literature on human rights (Risse and Sikkink 1999: 17-35). This model suggests that the process from repression to human rights consistent behaviour begins with regimes that violate human rights making tactical concessions to attain benefits such as financial aid. These concessions perfectly match the change in foreign policy preferences suggested in the model above. They are done to attain a good that is valued higher than the cost of transformation, in particular since this transformation may be regarded as purely rhetorical. The result is a conditional equilibrium as outlined above.

In the spiral model, this is, however, not the end of the story. From a discursive perspective, this equilibrium involves a change of human rights or foreign policy practices. Even if these were only meant as paying lip-service, while continuing the 'national walk', they nonetheless produce a platform that enables other actors to make legitimate claims that advance an identity transformation. In the case of human rights, this includes first and foremost human rights activists within the country and supported by transnational networks of human rights advocates. In the case of foreign policy, it is again a mixture of civil society agents from anti-militarist NGOs to university intellectuals and newspapers that may advance, for instance, a conciliatory stance towards Cyprus in the case of Turkey and vice versa.

Note that this feedback is produced through actors advancing their own preferences, but that it rests on a discursive transformation that enables them to do so. Their actions, in turn, and as the spiral model suggests, may eventually result in a change of action mode - the stage in which state behaviour is consistent with international norms not because of cost-benefit calculations, but because the norms are accepted as such.

A second feedback effect is less driven by conscious efforts of specific actors. Instead, its central mechanism is the routinisation of those superficial practices agreed to attain the material benefits of membership. Such routinisation has the potential to undermine existing identities in that it makes the norms expressed in 'superficial' policies stick. Political actors may thus find their identities transformed through routinisation processes without ever having deliberately agreed to such an identity change. Maybe even more importantly, new generations are brought up for whom norms that were originally only paid lip service to are a 'normal' part of life and therefore integrated into their identities so that the logic of appropriateness can set in. Whereas the spiral model thus delineates an actor-driven feedback effect, we may characterise this second feedback as predominantly discursive and thus incorporating structural elements.

The combined model suggests that to arrive at a more stable change of foreign policy behaviour, state identity needs to be transformed. Enlargement influences on state identity can be both direct and indirect. The reformulation of the constructivist part of the model suggests that state identity is transformed through socialisation as an enlargement effect, in turn leading to a change of preferences and/or action mode. The reformulation of the rationalist part of the model argues that actors may provide the ground for feedback effects on identity as a result of their rationalist behaviour in the enlargement process.

State identity thus stands out as the crucial factor in the process of the imposition of governance. The EU's power to impose its system of governance is therefore not only reliant on the applicant states' material interests, but to a considerable degree on their political self-identification as being part of and sharing basic norms and values of an international society with the EU at its centre (Diez and Whitman 2000). While its transformation leads to more stable outcomes, it is however, also much harder to change than to achieve tactical concessions in negotiations. This insight is not new (Mouritzen 1993; Wæver 1998: 99), and the example of Greece's foreign policy behaviour after becoming a member may indicate that socialisation processes as an effect of membership take place over rather long time periods.

The more successful strategy is thus not to hope for socialisation effects alone, but to achieve as many concessions as possible already in the enlargement process in order to set free the ghost that may later haunt those who resist change (for a similar argument in relation to why EU and NATO opted for enlargement, see Fierke and Wiener 1999). In practical terms, this means that the carrot of membership needs to be held out as long as possible; that one needs to push during membership negotiations for as many transformations as possible; and that the overall aim should always be to strengthen and enable those civil society agents that share basic norms to make legitimate claims against those resisting transformation. And indeed, the EU has so far been engaged in governing 'through the prospect of membership' (Friis and Murphy 1999: 226), rather than relying on later socialisation effects only.

4.5. Conditions for the transformation of state identity

This discussion about the link of domestic structure and foreign policy behaviour is part of the final and crucial issue to be addressed if state identity is identified as the central factor influencing the stable change of foreign policy behaviour: the facilitating conditions of state identity transformation. Besides domestic political structure, there are at least three further important factors.

a) Discursive translatability. A central variable in the literature on norms and international relations is the resonance between international and domestic norms (e.g. Risse et al. 1999: 156; Diez 1999b: 84-5). While the negotiation process may result in the installation of discursive traces on which actors may build, the resonance hypothesis points to already existing elements of domestic discourse that 'resonate' with international norms. In other words, even if the overall foreign policy discourse is dominated by practices of securitisation, there may be arguments used within this discourse that are at least not opposed to a norm of desecuritisation. The existence of such arguments makes it easier to build bridges to international norms and promote the latter by reference to the former. In Turkey, for instance, the Kemalist principle of 'peace at home, peace abroad' as well as regionalist projects in the Turkic states of the former Soviet Union would enhance the translatability of the desecuritisation norm into Turkish foreign policy discourse (Kazan 2001).

b) The representation of international structure. As mentioned above, power asymmetry is taken to explain why the CEEC's would follow the conditions set by the EU during the enlargement process. But asymmetry may also be expected to influence enlargement effects. In both cases, though, what is decisive is not material power as such, but its discursive representation. This argument is known from the English School definition of a Great Power - it is not only material resources that define a Great Power, but the recognition of a state as such that is important (Bull 1977: 202; Buzan 2000). Current member states may thus see Turkey in terms similar to the CEEC's, while Turkish politicians may see much less of an asymmetry, referring to the strategic importance of Turkey and its membership of other European organisations and NATO, and may therefore be less willing to adjust (Andersen 2000). At the other end of this spectrum, if the asymmetry is constructed as too strong, changes may be resisted to make clear that 'we are still important'. Both in Cyprus and in Turkey, such voices have been raised over the past years. The structure of CFSP still allows countries to bloc common actions, although constructive abstention according to Art. 23 TEU would be the 'normal' path. Similarly, geopolitics may matter not because of geographic determinism but because of the representation of space. Turkey may, for instance, refer to its 'bad neighbourhood', Cyprus to its importance as a European outpost in the Middle East.

c) Statecraft. Although all of the conditioning factors mentioned so far were structural in nature, I have stressed their discursive component: domestic structures enable civil society actors to make claims; norms may be translated into domestic discourse; international structure is represented in a particular way. All of these thus condition practice, but they are also dependent on practice to make a difference (Milliken 1999: 230; Diez 2001). Drawing on poststructuralist work as well as Classical Realism, Ole Wæver (1994) argues that those articulating foreign policy are of particular importance here, since they stand between the international and the domestic discourse. It is they who link these discourses, and who through these linkages insert new identities into the debates. In a sense, this is a rereading of the classical notion of statecraft, although of course 'state' may be a characterisation of diminishing adequacy. It reminds us that despite all these structural factors, there is always space for creativity to articulate identity, although of course such creative practice is never independent of structure; but the same is true vice versa. In the case of Turkey and Cyprus, there may thus also be a need for a person with such a creativity to rearticulate state identity (Salih 2000) - given his critical speeches in the past, Turkey's new president Ahmet Necdet Sezer may turn out to be such a person.

A final caveat relates to the issue of power as a two-way street mentioned above. In these considerations, my concern was still mostly with the question of an 'imposition' of governance. But the discussion of the conditions has now opened up routes through which identity may also be transformed the other way round. Norms from the applicant country discourses may be translated into European Union foreign policy discourse; geopolitical representations may be taken over by the EU as a whole; and creative practitioners may give the EU a new course - imagine Vaclav Havel as president of a EU member state! The mechanisms through which enlargement effects can work the other way round are worth further analysis that cannot be performed here. Suffice it to say at this point that what has been separated here for analytical purposes should be thought together, and that constructivism gives us some ideas about how these effects may come about.

5. Scenarios for the Future

5.1. Three scenarios

Returning to the issue of Turkey's and Cyprus's foreign policy in the context of future EU membership, there are only three realistic scenarios as long as the alternatives are either membership or non-membership. In the first two scenarios, Cyprus is taken up as a member, with the Cyprus conflict either solved (scenario 1) or not (2). In the third scenario, both Cyprus and Turkey become EU members. In this latter option, some solution for Cyprus is implied, since the EU has repeatedly stated this as a condition for Turkish membership, and since it is unlikely that Greece will agree to Turkey being taken up without such a solution. It is also unlikely that none of the two states will become a member, given Cyprus's strong overall standing in the negotiations, and its strong support by Greece within the EU.

(1) Cyprus becomes a member with the conflict solved. This would be an ideal scenario for the time being. Since the major factor of securitisation within Cypriot foreign policy was the Cyprus conflict itself, this factor would disappear. Furthermore, one of the obstacles for Turkish entry would be removed. The initial step would be taken, and the EU, through socialisation, could help to stabilise the changed state identity, with new foreign policy preferences and possibly a shift to a new action mode in which desecuritisation is the central norm. Unfortunately, the realisation of this scenario is not in the EU's hands. Without both Cypriot and Turkish membership, the catalytic effect, for a number of reasons, is unlikely to set in unless it is helped by developments outside the EU realm (this is elaborated in Diez 2000). Although these cannot be excluded, there is as yet little development towards such a solution.

(2) Cyprus becomes a member with the conflict remaining unresolved. At present, this seems to be the most likely scenario. But it is also the scenario in which the imposition of governance in the foreign policy realm is of utmost importance. The above model suggests that in this situation the EU would have to insist on a softening of Cypriot foreign policy towards Turkey, but also of its policy towards the Northern part. This would then ideally strengthen forces in Cypriot civil society (on both sides) to promote intercommunal activities without state regulation, thereby eventually undermining the de-facto border, which may initially be reified through a de-facto membership of only the Southern part of the island. The strengthening of alternative forces would also mean a furthering of a change in state identity. The chances of such a change will depend on the factors mentioned above, which are, however, hard to assess at this point. There are, for instance, competing discourses on the island which would be translatable into a desecuritisation discourse (Diez 2000: 25-6); they are, however, overwhelmed by a strong official representation. Should the latter prevail, would the EU run the risk of internalising a conflict that would threaten to undermine its own foreign policy governance (Allen 1998: 122; Brewin 1999: 163-4; Friis and Murphy 1999: 221; Smith 1996)

(3) Both Turkey and Cyprus become members. This scenario would not necessarily mean simultaneous membership, but Turkey would at least have to be on a clearly delineated path to membership. In this scenario, securitisations surrounding the Cyprus conflict would play a minor role. Here, the EU could again through socialisation effects help to transform state identity and achieve stability. Instead, the foreign policy behaviour of Turkey would be in the limelight. As far as its relations with Greece are concerned, it can be assumed that the same expectations would hold as for Turkish-Cypriot relations. The focus would thus be on Turkey's South-Eastern border, and again the EU would have to attempt to achieve as many concessions as possible in the negotiation process. This seems to be vital, since it would already undermine the military's influence, which, however, would also make the negotiation process as such rather tough. Again, the chances for the transformation of state identity seem to be rather open. On the one hand, the candidacy itself seems to have already strengthened a number of civil society forces, although the agenda of most of them is predominantly domestic. On the other hand, given Turkey's self-conception as a regional power vital to European interests, politicians may resist change with reference to their status. The conception as a regional power may, though, be turned into a positive force if the Kemalist 'peace at home, peace abroad' principle can be linked up with the European desecuritisation norm.

These three scenarios do not take into account a possibility that is becoming more and more likely in an EU with an increasing number of member states: an increasing flexibilisation and differentiation of membership through a softening of the EU's institutional borders (Croft et al. 1999: 80-82; Friis 1999: 211; Friis and Murphy 1999: 219, 227). In such a case, Turkey would become fully part of some integration sectors, but may be only associated with others (Buzan and Diez 1999: 52-55). It is unlikely that Turkish politicians would be satisfied with such a solution at this point, but since the general trend of integration points into this direction, such a possibility may sound more 'normal' and less like degradation in the future. Such a scenario would complicate things even further. In general, however, the above considerations could still be expected to hold. Before Turkey would be fully integrated into the CFSP area, for instance, it could (as is likely because of its NATO membership) be associated with the Council of Foreign Ministers to further socialisation, while at the same time it should be clear that as a condition for full membership, basic desecuritisation measures must be in place.

There is a limit to such a strategy, however. For one, it needs to be a hidden strategy, since if it is played open, applicants may not want to allow the imposition of governance to happen. Furthermore, it cannot be extended endlessly. There must always be a somewhat realistic chance for the applicant state to eventually become a member, since otherwise the membership carrot (and the stick of membership denial) is worthless (Wæver 1996). In the discussion about Turkey, this leaves only two options in the long run: Either both Turkey and the EU agree on clear targets and commitments, or they need to think about alternatives to EU membership openly.

5.2. Theoretical implications

Besides these policy-relevant conclusions, the considerations above also carried with them a number of implications for theorising enlargement, and beyond that for IR Theory in general. First and foremost, there was no doubt that the applicant states act 'rationally' in the sense that they follow their own subjective preference structure and try to advance what they perceive as to be in their national interest. Nonetheless, I have argued that constructivism plays a crucial role in analysing the imposition of governance. First, it turns our attention to the definition of rationality in a given context. This puts into question the dichotomy of interests versus ideas and leads to a focus on the discourses that establish specific purposes, and the ranking amongst them. Socialisation as an enlargement effect is then to be seen as a change in the dominant discourses, and consequentially a change in state identity and preferences. Paying closer attention to these processes may then also result in a critique of the underlying discourses and their specific world constructions; a path that was beyond the scope of this paper, but is nonetheless important to bear in mind (Diez 1999a).

The dichotomy of rationalism and constructivism was not only problematic as far as the opposition of ideas and interests was concerned. Using previous constructivist work in the human rights area, I have also shown how rationalist behaviour in the negotiation process leads to an initial change in discourse that may enable other actors to further this discursive change, and eventually lead to a transformation of state identity. Such a transformation I regarded to be more stable than a conditional equilibrium of preferences because of the sedimented and thus more 'stubborn' quality of state identity. In addition, it was in such a transformation that a change of the action mode towards a logic of appropriateness rather than consequentiality might lie.

In all of this, the point is that although authors such as Schimmelfennig (2000b: 116) are right in their assertion that 'it can be rational choice to behave appropriately', and that therefore enlargement as a process of international socialisation can easily be explained on the basis of rationalist assumption within institutionalist constraints, they underrate the importance of constructivist factors. These factors are not mere constraints to actors; they define the actors in the first place. Therefore, it is not surprising that Schimmelfennig (2000b: 132-4) eventually has to refer to 'the primacy of domestic conditions' when assessing the 'prospects of internalisation'. My argument in this paper was that this step, rather than the actors' behaviour in the negotiation process, is the more interesting and challenging one. And it is here that the cases of Cyprus and Turkey remind us of the importance of foreign policy behaviour when we analyse 'internalisation' as an effect of enlargement. Looking at these cases, the imposition of governance is a much more complicated process than the willingness of some CEECs to adjust their domestic structures may at first suggest.

References

Adamson, Fiona B. (2000) "Democratisation and the Domestic Sources of Foreign Policy: Turkey in the 1974 Cyprus Crisis", in: Political Science Quarterly, forthcoming.

Adler, Emanuel (1997) "Imagined (Security) Communities: Cognitive Regions in International Relations", in: Millennium: Journal of International Studies 26 (2), pp. 249-277.

Allen, David (1998) "Wider but Weaker or the More the Merrier? Enlargement and Foreign Policy Cooperation in the EC/EU", in: John Redmond and Glenda G. Rosenthal (eds.), The Expanding European Union: Past, Present, Future (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner), pp. 107-124.

Andersen, Ellen Ø. (2000) "Tyrkiet i tvivl om EU", in: Politiken, 30 May 2000, 1st section, p. 14.

Banchoff, Thomas (1999) "German Identity and European Integration", in: European Journal of International Relations 5 (3), pp. 259-289.

Brewin, Christopher (1999) "Turkey, Greece and the European Union", in: Clemens H. Dodd (ed.), Cyprus: The Need for New Perspectives (London: Eothen), pp. 148-173.

Bull, Hedley (1977) The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics (New York: Columbia University Press).

_____ (1982) "Civilian Power Europe: A Contradiction in Terms?", in: Journal of Common Market Studies 21 (1), pp. 149-170.

Buzan, Barry (2000) "Reflections on the Meaning of 'Great Power'", manuscript under review.

______; Diez, Thomas (1999) "The European Union and Turkey", in: Survival 41 (1), pp. 41-57.

______; Wæver, Ole; de Wilde, Jaap (1998) Security: A New Framework for Analysis (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner).

______; Wæver, Ole (2001) Regions and Powers (forthcoming).

Clarke, Michael; Smith, Steve (1989) "Perspectives on Foreign Policy Systems: Implementation Approaches", in: Michael Clarke and Brian White (eds.), Understanding Foreign Policy: The Foreign Policy Systems Approach (Aldershot: Edward Elgar), pp. 163-184.

Constantinou, Costas; Papadakis, Yiannis (1999) "The Cypriot State(s) in Situ: Cross-Ethnic Contact and the Discourse of Recognition", manuscript under review.

Croft, Stuart; et al. (1999) The Enlargement of Europe (Manchester: Manchester University Press).

Diez, Thomas (1999a) "Riding the AM-Track through Europe; or, The Pitfalls of a Rationalist Journey through European Integration", in: Millennium: Journal of International Studies 28 (2), pp. 355-369.

_____ (1999b) Die EU lesen: Diskursive Knotenpunkte in der britischen Europadebatte (Opladen: Leske+Budrich).

______ (2000) "Last Exit to Paradise? The EU, the Cyprus Conflict, and the Problematic 'Catalytic Effect'", COPRI-Working Papers 4-2000 (Copenhagen: Copenhagen Peace Research Institute). To appear in: Thomas Diez (ed.), Modern Conflict, Postmodern Union: Cyprus and the European Union (Manchester: Manchester University Press), 2001.

_____ (2001) "Europe as a Discursive Battleground: The Study of Discourse and the Analysis of European Integration Policy", in: Cooperation and Conflict 36, forthcoming.

_____, and Richard Whitman (2000) "Analysing European Integration, Reflecting on the English School: Scenarios for an Encounter", COPRI-Working Papers, forthcoming.

Duchéne, François (1972) "Europe's Role In World Peace", in: Roger Mayne (ed.), Europe Tomorrow: Sixteen Europeans Look Ahead (London: Fontana), pp-pp.

European Commission (1999a) Reguar Report from the Commission on Progress towards Accession: Cyprus - October 13, 1999; http://www.europa.eu.int/comm/enlargement/cyprus/rep_10_99/index.htm.

_____ (1999b) Reguar Report from the Commission on Progress towards Accession: Turkey - October 13, 1999; http://www.europa.eu.int/comm/enlargement/turkey/rep_10_99/index.htm.

Feldman, Lily Gardner (1999) "Reconciliation and Legitimacy: Foreign Relations and Enlargement of the European Union", in: Thomas Banchoff and Mitchell P. Smith (eds.), Legitimacy and the European Union: The Contested Polity (London: Routledge), pp. 66-90.

Ferguson, James (1990) The Anti-Politics Machine: 'Development', Depoliticization and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Fierke, Karen M.; Wiener, Antje (1999) "Constructing Institutional Interests: EU and NATO Enlargement", in: Journal of European Public Policy 6 (5), pp. 721-742.

Finnemore, Martha (1996) National Interests in International Society (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press).

Foucault, Michel (1991) "Governmentality", in: Graham Burchell, Colin Gordon and Peter Miller (eds.), The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality (Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf), pp. 87-104.

Friis, Lykke (1999) An Ever Larger Union? EU Enlargement and European Integration (Copenhagen: DUPI).

_____; Murphy, Anna (1999) "The European Union and Central and Eastern Europe: Governance and Boundaries", in: Journal of Common Market Studies 37 (2), pp. 211-232.

Ginsberg, Roy H. (1999) "Conceptualizing the European Union as an International Actor: Narrowing the Theoretical Capability-Expectations Gap", in: Journal of Common Market Studies 37 (3), pp. 429-454.

Glarbo, Kenneth (1999) "Wide-awake Diplomacy: Reconstructing the Common Foreign and Security Policy of the European Union", in: Journal of European Public Policy 6 (4), pp. 634-651.

Grabbe, Heather (1999) "The Transfer of Policy Models from the EU to Central and Eastern Europe: Europeanisation by Design?", Paper for the 1999 APSA Annual Meeting, Atlanta, 2-5 September 1999.

Hasenclever, Andreas, Mayer, Peter; Rittberger, Volker (1999) Theories of International Regimes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Hill, Chris (1990) "European Foreign Policy: Power Bloc, Civilian Model, or Flop?", in: Reinhard Rummel (ed.), The Evolution of an International Actor: Western Europe's New Assertiveness (Boulder, CO: Westview), pp.-pp.

Jachtenfuchs, Markus; Kohler-Koch, Beate (1996) "Regieren im dynamischen Mehrebenensystem", in: Markus Jachtenfuchs and Beate Kohler-Koch (eds.), Europäische Integration (Opladen: Leske + Budrich), pp. 15-44.

Jacoby, Wade (1998) "Talking the Talk: The Cultural and Institutional Effects of Western Models", Paper for the conference "Post-Communist Transformation and the Social Sciences: Cross-Disciplinary Approaches", Berlin, 30-31 October 1998.

Jung, Dietrich; Piccoli, Wolfango (2000) "The Turkish-Israeli Alignment: Paranoia or Pragmatism", in: Security Dialogue 31 (1), pp. 91-104.

Jørgensen, Knud Erik (1997) "PoCo: The Diplomatic Republic of Europe", in: Knud-Erik Jørgensen (ed.), Reflective Approaches to European Governance (Basingstoke: Macmillan), pp. 167-180.

Kazan, I_il (2001) "Turkey and the Eastern Mediterranean", to appear in: Thomas Diez (ed.), Modern Conflict, Postmodern Union: Cyprus and the European Union (Manchester: Manchester University Press).

Keohane, Robert O. (1984) After Hegemony (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

Kohler-Koch, Beate (ed.) (1989) Regime in den internationalen Beziehungen (Baden-Baden: Nomos).

Kohler-Koch, Beate; Eising, Rainer (eds.) (1999) The Transformation of Governance in the European Union (London: Routledge).

Kooiman, Jan (1993) "Findings, Speculations and Recommendations", in: Jan Kooiman (ed.), Modern Governance: New Government-Society Interactions (London: Sage), pp. 249-262.

Krasner, Stephen D. (1983) "Structural Causes and Regime Consequences: Regimes as Intervening Variables", in: Stephen D. Krasner (ed.), International Regimes (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press), pp. 1-21.

March, James G.; Olsen, Johan P. (1989) Rediscovering Institutions (New York: The Free Press).

McLaren, Lauren M. (2000) "Turkey's Eventual Membership of the EU: Turkish Elite Perspectives on the Issue", in: Journal of Common Market Studies 38 (1), pp. 117-129.

Milliken, Jennifer (1999) "The Study of Discourse in International Relations: A Critique of Research and Methods", in: European Journal of International Relations 5 (2), pp. 225-254.

Moravcsik, Andrew (1998) The Choice for Europe: Social Purpose and State Power from Messina to Maastricht (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press).

Mouritzen, Hans (1993) "The Two Musterknaben and the Naughty Boy: Sweden, Finland, and Denmark in the Process of European Integration", in: Cooperation and Conflict 28 (4), pp. 373-402.

Müftüler-Bac, Meltem (1997) Turkey's Relations with a Changing Europe (Manchester: Manchester University Press).

Neumann, Iver B. (1998) "European Identity, EU Expansion, and the Integration/Exclusion Nexus", in: Alternatives 23 (3), pp. 397-416.

Olgun, Mustafa Ergün (1999) "Turkey's Tough Neighbourhood: Security Dimensions of the Cyprus Conflict", in: Clemens H. Dodd (ed.), Cyprus: The Need for New Perspectives (London: Eothen), pp. 231-259.

Pace, Roderick (2000) "Small States and the Internal Balance of the European Union: The Perspective of Small States", in: Jackie Gower and John Redmond (eds.), Enlarging the European Union: The Way Forward (Aldershot: Ashgate), pp. 107-122.

Paul, T.V.; Hall, John A. (eds.) (1999) International Order and the Future of World Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Rasmussen, Mikkel Vedby (1998) "Post War: Reflections on the Integration of the European Security Community", in: Anders Wivel (ed.), Explaining European Integration (Copenhagen: Copenhagen Political Studies Press), pp. 78-99.

Risse, Thomas; Sikkink, Kathryn (1999) "The Socialization of International Human Rights Norms into Domestic Practices", in: Thomas Risse, Stephen C. Ropp and Kathryn Sikkink (eds.), The Power of Human Rights: International Norms and Domestic Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 1-38.

Rose, Nikolas; Miller, Peter (1992) "Political Power beyond the State: Problematics of Government", in: British Journal of Sociology 43 (2), pp. 173-205.

Rosenau, James; Czempiel, Ernst-Otto (eds.) (1987) Governance without Government: Order and Change in World Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Russett, Bruce (1993) Grasping the Democratic Peace: Principles for a Post-Cold War World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Salih, Khaled (2000) "Turkey, the EU and the question of democratisation in Turkey" (Paper, Odense University, June 2000).

Schimmelfennig, Frank (2000a) The Enlargement of European Regional Organizations: Questions, Theories, Hypotheses, and the State of Research (Paper prepared for the workshop 'Governance by enlargement', TU Darmstadt, June 2000).

_____ (2000b) "International Socialization in the New Europe: Rational Action in an Institutional Environment", in: European Journal of International Relations 6 (1), pp. 109-139.

Smith, Michael (1996) "The European Union and a Changing Europe: Establishing the Boundaries of Order", in: Journal of Common Market Studies 43 (1), pp.5-28.

Twitchett, Kenneth J. (1976) Europe and the World: The External Relations of the Common Market (London: Europa).

Urwin, Derek W. (1995) The Community of Europe: A History of European Integration since 1945; second edition (London: Longman).

Wendt, Alexander (1999) Social Theory of International Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Whitman, Richard G. (1998) From Civilian Power to Superpower? The International Identity of the European Union (Basingstoke: Macmillan).

Wæver, Ole (1994) "Resisting the Temptation of Post Foreign Policy Analysis", in: Walter Carlsnæs and Steve Smith (eds.), European Foreign Policy: The EC and Changing Perspectives in Europe (London: Sage), pp. 238-273.

______ (1995) "Securitization and Desecuritization", in: Ronnie D. Lipschutz (ed.), On Security (New York: Columbia University Press), pp. 46-86.

_____ (1996) "Europe's Three Empires: A Watsonian Interpretation of Post-Wall European Security", in: Rick Fawn and Jeremy Larkins (eds.), International Society after the Cold War (Basingstoke: Macmillan), pp. 220-260.

______ (1998) "Insecurity, Security, and Asecurity in the West European Non-War Community", in: Emanuel Adler and Michael Barnett (eds.), Security Communities (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 69-118.

Øhrgaard, Jakob C. (1997) "'Less than Supranational, More than Intergovernmental': European Political Cooperation and the Dynamics of Intergovernmental Integration", in: Millennium: Journal of International Studies 26 (1), pp. 1-29.