|

|

|

|

|

|

Lessons Learned from Former Yugoslavia

Wolfgang Biermann and Martin Vadset

Copenhagen Peace Research Institute

Report of Conference

held in Copenhagen, Denmark

12-14 April 1996

Parts of this Workshop report will be actualized and incorporated into a book by Mssrs. Biermann and Vadset entitled UN Peace-keeping in Trouble - Lessons Learned from the Former Yugoslavia. The book will be published in early 1998 by the Avebury/Ashgate publishing group.

UN Peacekeeping after the Cold War shows that options of what the international community can achieve by intervening into or after civil war-like conflicts are in reality more limited than political or moral desires may demand.

Finding out the criteria of the 'practicability' and feasibility of UN mandates is a challenging task for research as well as for political and military decision-makers. The Danish Norwegian Research Project on UN Peacekeeping (DANORP) has considered the peacekeepers themselves as a best resource to answer the question of 'practicability' of mandates they are expected to implement, and to identify political and operational "secrets of success" or "reasons for failure".

DANORP undertook several steps to achieve a comprehensive picture of the challenges peacekeepers are facing in a civil war-like environment, among them open interviews with top-level civilian and military practitioners, a questionnaire-based survey among hundreds of UNPROFOR officers and two major UN Commanders Workshops in 1995 and 1996.

NUPI and COPRI (Copenhagen Peace Research Institute) are jointly publishing a DANORP Working Paper which gives insight into the discussion of key personnel at the 2nd UN Commanders Workshop held in Copenhagen (Denmark) 12-14 April 1996.

The report gives examples of over-expectations towards UNPROFOR, but it also shows an impressing record of successful activities of the UN to contain and reduce conflict in former Yugoslavia. First results of the UNPROFOR survey (May 1995 to March 1996) reveals opinions of UN officers about what could and could not be accomplished by UN peacekeepers.

The authors, Dr. Wolfgang Biermann and Lt.Gen. Martin Vadset, are presently working at NUPI and are writing a book on "UN Lessons Learned from Former Yugoslavia."

About DANORP

The Danish-Norwegian Research Project on UN Peacekeeping (DANORP) was initiated in 1994 by a grant from the Copenhagen Peace Research Institute (COPRI). Since September 1996 it is based jointly at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Norway and at COPRI, Denmark. Project support has been provided by the Danish and the Norwegian Government and the German Friedrich Ebert Foundation. The Project Leader is Dr. Wolfgang Biermann (D) and the Senior Project Advisor is Lieutenant General Martin Vadset (N). The main aim of the project is to investigate the 'lessons learned' by practitioners regarding the applicability and possible modifications of peacekeeping principles and procedures in the context of UN missions to 'new' civil war-like types of conflict. It also touches upon issues like humanitarian aid, repatriation, human rights and mediation.

Key military and civil personnel of the UN and regional organizations have been targeted for consultation. Wide-ranging interviews have been supplemented by an international questionnaire distributed among UNPROFOR officers and by two UN Commanders Workshops which DANORP organized in Oslo (1995) and Copenhagen (1996).

The 2nd UN Commanders Workshop at Copenhagen 12 - 14 April 1996 focused on windows of opportunity and realistic options during several phases of mediation efforts in Former Yugoslavia from 1991 up to the present. In order to permit frank and open discussions of 'lessons learned', the 'Rules of Engagement' at the UN Commanders Workshops adhered to the principles of 'no quotations' attributed to individual participants and of 'no press'. The media had the opportunity to talk to participants in separate press conferences. However, this non-attributed report covers the main arguments and conclusions of the 2nd UN Commanders Workshop's discussions. It reflects and outlines the mainstream views expressed or amended by the participants.

The report has the character of a Working Paper and will be incorporated in the final DANORP research report on LESSONS LEARNED FROM FORMER YUGOSLAVIA. Therefore we are open to further amendments and proposals.

Preliminary results of the questionnaire survey are attached in Annex A. The Conference Programme and its participants are listed in Annex B.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to all the participating military and civilian leaders who contributed with their discussions and manuscripts to this report. We want to acknowledge in particular the excellent assistance of the Rapporteur, Lt.Col. Charles Dobbie (UK) and the Co-Rapporteur, Lt.Col. Willem Steijlen (NL).

We hope that this report contributes to a substantial discussion of 'lessons learned' in order to improve conditions and preparedness for UN Peacekeeping, keeping in mind, what could and - as one Workshop delegate emphasized - what should not be done in a civil war-like conflict. We hope that the report raises interest in the upcoming DANORP report on Lessons Learned From Former Yugoslavia .

| Oslo, November 1996 Dr. Wolfgang Biermann |

Lt.Gen. Martin Vadset |

Highlights from the Discussion

Peace Plans and Enforcement

“On 2 May 1993 the Vance-Owen plan was accepted. Mediators went from capital to capital of the NATO nations.... The message received was: 'You cannot count on combat forces, only peacekeepers'. There was no way to enforce anything. Planning with the UN and EU therefore had to proceed on that basis.”

Similarity of Peace Plans and the Price for Peace

“The peace agreements from Carrington in 1991 onwards were amazingly similar. It is a matter of regret that the Spring 1993 (Vance-Owen Plan) and the Autumn 1993 agreements (Stoltenberg-Owen Plan) were finally not accepted. The Dayton Agreement is similar to these agreements.... It was argued that the Bosnian Muslims should get more land area. The 1993 agreement gave them 33%. The Dayton agreement dropped it to 28%. ... It was also argued that in principle it was unacceptable to recognize land taken by force, .... that it was wrong to carve up Bosnia and that it was necessary rather to establish a multi-cultural society. But ... violation of these principles was unavoidable, in Dayton as well as in earlier peace agreements. ... High moral goals were paid for with the lives of Bosnian people. The price of a perfect peace was a long war. That should be remembered in future negotiations.”

Wrong Hopes for 'Right Medicine'

“Military thinkers would like to draw some general lessons from our collective experiences. ...As we search for principles, I want to caution against making our efforts look too systematic -- as if diplomats and military planners were able to operate like physicians, diagnosing a peace 'disease' and then applying a peacekeeping medicine -- a political/military solution of some kind. As demonstrated by previous discussions here, this analogy is blatantly wrong for the case of former Yugoslavia...”

Experimentalism

“If there is any meaning to the term 'mission creep' in this context, it is that we crept up the scale of commitment, as one thing after another did not work.

...Political realities will impair the ability of diplomats and military planners to design the 'right-size' solution and level of commitments at the beginning. For peace operations where classic peacekeeping is not feasible, and where no single national interest is at stake, we may be constrained to take a 'trial and error' approach. ...We have to go through the learning process on what works and what does not. The press will certainly enjoy criticising us during the process....”“... It is fair to say that the former Yugoslavia is the most complex peace challenge to date in the Post-Cold War world, with well-equipped warring factions, with leaderships sophisticated in negotiating with neighbouring patron states, but without major strategic consequences for any major Western power. In this situation, perhaps it was inevitable that we engaged in an experiment.”

Over-expectations

“... There was a consistent tendency for political and military authorities to overstate the efficacy and inventiveness of military forces that were given set limits to operate with. There were over-expectations on what the military would be able to achieve with various versions of peacekeeping, and combinations of peacekeeping and the threats to use force. ...

For IFOR, I would say that over-expectation is also a problem -- though not with the same impact as the earlier cases. IFOR's latitude to use force is a fact. But this does not mean that IFOR is the right tool for facilitating civil reconstruction, or introducing nation-wide law and order into B-H.”

The Way to IFOR

“I want to distinguish between peace enforcement and peace implementation, with the key difference that we put the burden of responsibility on the former warring factions, not the peace force. .... Prior to Dayton, it is debatable whether there was a peace to keep much less one to enforce. For Dayton, it was important that the Parties freely engaged in the terms and in the territorial settlement of the Peace Agreement.

There was a sense in which the environment was ripe for a peace agreement -- not only for the international community but for the Parties. The Parties had to see themselves as gaining from the Agreement.”

The Difference between UNPROFOR and IFOR

“... IFOR is implementing their Peace Agreement, not enforcing an imposed solution. This distinction underpins the whole NATO involvement and the IFOR mission, including the one-year duration and, of course, it makes NATO's job much simpler than UNPROFOR's ever was. UNPROFOR never had the benefit of such a solid agreement. ...

You will recall the sloping shoulder syndrome, the constant turning to UNPROFOR when too difficult a situation had to be faced up to, the desire to turn the UN into the scapegoat for their own failures. Now they are learning that they must solve problems themselves and we see each success as yet more evidence that each achievement makes it that bit harder for them to go back to war. For the first time recently, I have detected a genuine desire to reap the benefits of ... peace. It is very encouraging.”

Why Dayton Can Work

“The Dayton plan will work for two reasons. First it will be difficult for those who want to fight within the Former Yugoslavia to mobilize people. Any such move would be extremely unpopular. All the leaders have lost part of their authority. An international presence will discourage a resumption of hostilities. Second, as long as the US is actively involved, it will work because of the unique authority of the US to make it work.”

Responsibilities

“What did we learn in terms of general principles? If I had to point to one thing, I would say we learned something about putting the responsibility for peace on the former warring factions. Given a peace agreement, the military forces implementing the peace need to be aggressive and consistent in refusing to take responsibility for the factions' behaviour.”

Impartiality

“I promised to do my utmost to contribute to a negotiated solution and to be impartial. .... But the parties and international community often objected, asking: 'How can you be impartial to an aggressor?' ...However, It was not possible to gain a lasting peace without the agreement of each of the parties. ... Logically speaking there could be no peace agreement without impartiality. The Dayton Peace Agreement could not have been agreed upon without impartiality.”

Peacekeeping and the Use of Force

“There was an increasing pressure on the UN to use force. Close air support to defend the peacekeepers was used and worked well. Then there was pressure for major air strikes. ... Those pressing for the use of force were often not themselves involved. ... UN troops were peacekeepers. General Michael Rose was strong enough to resist pressure because of the risk to the lives of his own troops.....The hostage-taking of thinly spread peacekeepers (on one occasion 240) following air attacks proved the point.”

Preventive Deployment in Macedonia

“The UN and the US struggle with the same problems: how to select among competing crises, less willingness to deploy fewer forces, and budget shortfalls, In this environment, preventive concepts hold a weak hand. Major powers tend to deploy soldiers only where they have important or vital interests, yet UNPREDEP shows that pre-crisis diplomacy and preventive deployment are cost-effective and practical in nature. ...

On one particular occasion, the Macedonian government complained that 'their' UN commander should not contact the potential enemy, highlighting a problem of host nation "ownership" of a preventive force. Nonetheless, the commander in March 1994 began meeting with the military command in Belgrade. In June and July of 1994, a dangerous military confrontation between Serbia and Macedonia, was defused when the UN-Commander intervened and mediated a Serbian withdrawal from an incursion into Macedonia. Had the UN not been there, the confrontation could have escalated.”“... In 1994 US State Department officials identified as a significant risk the potential for a mass exodus of ethnic Albanian refugees from the Kosovo in Serbia through Macedonia to the Greek border, leading to conflict between Greece and Turkey. But UNPREDEP concluded that the risk was low, and reported its assessment regularly to UNPROFOR and to the US and Nordic governments through their unit national chains of command, and to visitors. Many US representatives admit today that they have learned a lot, and that they have a better understanding of traditional peace-keeping after serving couple of years with 'Nordics' in Macedonia. Today the co-operation between the US and Nordic Battalions can only be described as excellent. Very useful exchange of soldiers programs and joint exercises have taken place.”

Eastern Slavonia

“UNTAES could make its programme work. It all depends on the sincerity of Tudjman and Milosevic, however, since any success would have to include both presidents' willingness to support the UN's efforts. It would also depend upon the preparedness of the parties to co-operate. There are certain concerns what might happen after UNTAES.”“I am concerned that Eastern Slavonia could be forgotten. It deserves focus. There are 200,000 people there. Another raid into Eastern Slavonia is possible unless an international focus is put there. Such an attack would again complicate matters in the region. ”

EU Foreign Policy

“We must remember that the EU represents 15 foreign policies and not one (like the USA). Russia, Japan and China were not interested. US power and authority is unique. If the US and Europe ever disagree seriously that will have dramatic impact on European security. US political leadership is a blessing. ... The only way of strengthening EU foreign policy is to co-ordinate it.”

Window of Opportunity 1991/92

The Vance plan for Croatia -- Deployment of UNPROFOR

The Vance Plan.

1. On 27 November 1991, UN Security Council Resolution 721 (1991) endorsed efforts for the deployment of a UN peacekeeping operation in Croatia/Yugoslavia. 1992 heralded the Vance plan. An Implementing Accord was signed in Sarajevo on 2 January 1992. The UN was represented on this occasion by a military liaison officer and a team of civilians who were present at the signing. The UN Secretary General sent military liaison officers with the task of promoting maintenance of the cease-fire. Six weeks later, on 15 February 1992, the UN Security Council confirmed the acceptance of the Cyrus Vance Plan by all parties and agreed to establish UNPROFOR. On 21 February UN Security Council Resolution 743 approved financial support of UNPROFOR for one year.

2. The Vance plan was a result of a six-month negotiation process. There was never any question of European capitals providing combat troops for the plan. No enforcement, only peacekeeping was an available option. Planning with the UN and EU had to proceed on that basis. The plan's aims were summarized as follows:

- The demilitarization of UNPAs 2 (to protect the Serbs within the UNPAs).

- The restoration of Croatian authority in the UNPAs.

- To facilitate the return of displaced families to the UNPAs.

It was significant that the measures detailed above were agreed upon only by Tudjman and Milosevic. The Krajina Serbs objected strongly, e.g. that the UNPROFOR mandate in Croatia did not have their consent.

The UNPROFOR Mission. 3

3. UNPROFOR was initially deployed in Croatia, with a Headquarters in Sarajevo which at that time, early 1992, before the recognition of its independence, was 'peaceful'. Subsequently, with the escalation of the civil war in Bosnia, its mandate was extended to Bosnia and - as preventive deployment - to the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM). In addition, UNPROFOR had an operational mandate in Serbia and Montenegro and a liaison presence in Slovenia.

On 31 March 1995, the UNSC

4

decided to restructure and rename UNPROFOR, replacing it by three Peacekeeping operations (PKOs):

UNCRO

5

(Croatia), UNPROFOR (Bosnia) and UNPREDEP

6

(Macedonia), interlinked by the UNPF-HQ

7

in Zagreb. The UNPF-HQ was also responsible for liaison with the governments in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and other concerned governments as well as with NATO.

4. UNPROFOR had a threefold purpose:

- Second, after it was extended to Bosnia-Herzegovina, it sought to contain the conflict and mitigate its consequences by imposing constraints on the belligerents through the establishment of such arrangements as a 'No-Fly Zone', Safe Areas (SAs) and exclusion zones like the Total Exclusion Zone (TEZ) of February 1994 in Sarajevo and April 1994 in Gorazde.

- Third, UNPROFOR sought to promote the prospects for peace by negotiating local cease-fires and other arrangements, maintaining these where possible and providing support for measures aimed at an overall political settlement.

Deployment.

5. In the beginning of UNPROFOR in Croatia, UN military assets amounted to 4 battalions from Canada, Nepal, Argentina and Denmark plus 100 UN civil police (UN CIVPOL) and civilian staff. Deployment followed the arrival of the advance party on 5/6 March 1992.

UNPROFOR with its military and civilian components was deployed in areas containing significant Serb minorities where inter-communal tension had led to armed conflict.

Civil Affairs work in Sector West (Croatia) focused on dealing with local authorities and the people of the region and implementing a series of confidence-building measures - all of which sought to establish normality in daily life.

6. Major tasks of the UNPROFOR mandate included carrying out or supporting demilitarization, monitoring and overseeing the work of the local police forces, and facilitating the return of all displaced persons (for whom the lead agency was the UNHCR). The daily work of Civil Affairs in the early period tried to disseminate correct information. This involved explaining the mandate and the concept of implementation, emphasizing that UNPROFOR was not an occupation force but a neutral peacekeeping force. Still, in both, the Croat as well as Serb entities, the UN was perceived as biased.

Activities.

7. Demilitarization was the key to many activities of UNPROFOR in Croatia which included the following:

- Periodic meetings at the Demarcation Line (Zones of Separation). This included the reunion of family members.

- Village Visitation Programme. Displaced persons were allowed to visit the villages (deserted or destroyed) of their origin located in other parts of the Sector. These displaced people also undertook damage assessments and clearing-up work. Agricultural activities also took place for displaced persons in the areas controlled by the opposing faction. Visitation was an important element of normalization process.

- Economic Rehabilitation and Reconstruction: Small-scale, quick-impact projects were set up through the UN. Bilateral and multi-lateral financial arrangements were made.

- Humanitarian Assistance. This included the delivery of food packages and medical care. 40% of families were mixed Serb/Croatian.

- Human Rights. Monitoring human rights included reviewing such things as alleged harassment, employment opportunities and access to schools. The UN Civil Affairs office intervened with local and, if necessary, with central authorities.

- Repair of Physical Infrastructure. For instance through direct contacts between the parties, water was provided in Serb areas and electricity in Croat regions.

Obstacles to Implementation.

8. A variety of obstacles to the implementation of the Vance Plan were caused by UN procedures:

- Unclear Mission Objective. The mission objective was unclear. This was reflected in an inconsistent long-term strategy. There was also weak linkage between policy and implementation with no discernible connection between political negotiators and those implementing the agreement on the ground.

- Inconsistent UN Security Council Resolutions. Some were not consistent (for example, the definition of 'substantial minorities' and the basis on which the UN Protected Areasin Croatia were formed). There were also problems with the Pink Zones 8 concept.

- Weak Co-ordination and Co-operation. UNPROFOR's various components (military, Civil Affairs, UNCIVPOL and UNMOs) were not well co-ordinated.

- Lack of Dynamism. Owing to lack of regular contact with the UNPROFOR HQ in Sarajevo there were no guidelines for periods of 7 to 8 weeks for the civilian element deployed in Croatia. As a result the tendency was to focus on day-to-day problems. And that meant a lack of vision for the future and a non-dynamic approach. The mandate was viewed as a ceiling, not a floor. As a result, the spirit of the mandate was not fulfilled.

- Lack of Community Development. There was no concept for post-conflict community development. Dealings were mainly made with the authorities in a top-down approach rather than working upwards through the communities. More people should have been co-opted into joint activities. With assistance of the UN, the communities in war-torn societies needed to experience more relatively simple but noticeable improvements.

- Poor UN Media. With the exception of a few minutes of air-time per day, UN media was practically non-existent. The regional media of the parties was able to disseminate biased information and manipulate the public perception of the mandate and associated operations.

- Insufficient Involvement of Local Communities in the Peace Process. There were too few innovative ideas to tie people into the peace process. - Lack of Consistency. There was a lack of consistency in applying pressure to the parties concerned.

- Mis-match of Troop Commitments to Requirements. A continued deficiency in UNPROFOR was that in Croatia (as well as later in Bosnia) there was a significant mis-match between the estimated requirements of troop levels with the numbers that the UN Security Council actually authorized. The gap between requirement and provision was huge:

The Vance Plan was estimated to require 40,000 troops to secure the protected areas in Croatia. The UN Security Council authorized 13,000. BHC

9

required between 30,000 and 60,000 troops. The UN Security Council authorized 8,000.

UN Protected Areas (UNPAs) - Lesson Learned.

9. UNPROFOR established the UNPAs in Croatia from April 1992.

- It was pointed out by a Workshop participant that the UN had not always withdrawn in the face of attack. In the Syrian attack on Golan, the Egyptian attack on the Barlev Line along the Suez Canal, and in the face of attacks in South Lebanon, UN forces stayed in place but were overrun. - In another case, in Sector West of Croatia, the Canadian UNPROFOR troops had, in fact, deployed their heavy weapons and were ready to resist encroachments. As a result the situation was contained in that area.

The lesson was that the UN had to be firm and use tactics that would be known and understood by the parties. If that failed at least the UN would have obeyed their mission and done their best, and the UN's evident determination would create confidence.

It was not possible to co-locate with one party to the conflict and preserve impartiality.

The Unarmed Option.

10. Some Workshop participants questioned whether it might have been better not to have introduced armed troops at all. Using only unarmed personnel (UNMOs and UNCIVPOL) might have achieved the same results. It was argued that deploying troops sent the wrong signal to the parties and created false expectations. Each party regarded armed UN troops as a fighting force that might be used by them to advance their own interests.

Window of Opportunity 1993/94

Vance/Owen and Stoltenberg/Owen Plan for Bosnia-Hezergovina

General Course of Events. 10

11. In January 1993, the chairmen of ICFY, Cyrus Vance and Lord Owen presented a draft agreement (Vance-Owen Plan) on cessation of hostilities, a constitution and a map dividing BH into ten provinces. It was signed by the leaders of the Bosnian Muslims and Croats in March 1993. After - under high international pressure - Karadzic signed the plan 2 May 1993 in Athens, the Bosnian Serbs who then controlled 70% of Bosnia, rejected it in a referendum. The Bosnian Serbs had at that time no motivation to accept an agreement based on the Vance-Owen Plan. 11

12. 21 September 1993, a new peace agreement (Stoltenberg-Owen-Plan) was accepted by the leaders of each of the three Bosnian parties, but was a few days later rejected by the Bosnian Muslims parliament. 12

13. At the end of 1993, Croatia was stable. The Christmas truce in Croatia in 1993 lasted into 1994, and took also effect in parts of Bosnia. Cease-fire lines were more or less stable. All over the mission area there were weapon storage sites, signs of demilitarization, and military police replacing combat units.

14. In February 1994 the Total Exclusion Zone (TEZ) was established around Sarajevo, another one followed in Gorazde in April 1994. The Washington Framework Agreement of 1 March 1994 between Bosnian Croats and Moslems represented a breakthrough which created the Muslim/Croat Federation. This set the scene for a classic peacekeeping operation in which forces were to be separated and intense fighting brought to a conclusion.

15. Flash points were Sarajevo and the exclusion zone, Gorni Vakuf, Vares pocket, Brcko corridor, Bihac and Gorazde. Events in Gorazde in April 1994 represented a dress rehearsal for 1995. 13 There was a cease-fire in Sarajevo monitored by UNPROFOR but no-man's land was dominated by Bosnian Government forces within two days of the cease-fire being announced.

Safe Areas.

16. In April 1993, UN Security Council Resolution 824 established the new concept of Safe Areas. The aim of setting up safe areas at Sarajevo, Bihac, Tuzla, Srebrenica, Zepa and Gorazde was to protect civilians and not opposing forces deployed in the areas. The Commander of UNPROFOR, General Wahlgren, made local agreement to demilitarize the safe areas and informed HQ New York. The 'Agreement for the Demilitarization of Srebrenica' signed in Sarajevo on 17 April 1993 by General Mladic and General Halilovic under the aegis of General Wahlgren specifically excluded the presence of armed persons or units other than UNPROFOR within and around Srebrenica. Canadian troops deployed and on 22 April 1993 General Wahlgren reported that the areas were fully demilitarized and that the UN had full responsibility for them.

However, on 3 June 1993, a new UN Security Council Resolution (836) afforded specific permission to Bosnian government military and paramilitary units to remain within the safe areas. This was a blatant violation of the impartiality principle and of the safe havens principles under international humanitarian law.

14

By failing to endorse the agreement reached by the UN Force Commander in the field, the UN Security Council action led to the failure of the safe areas concept.

17. After 11 months and many incidents it was learned, in fact, that the UNSG 15 had himself suggested full demilitarization by both sides within and around the safe areas. 16 The parties involved lacked confidence in the UN - a vital requirement if areas were to be handed over to UN control. As a result the areas were abused as resting locations for troops and the UN lost its credibility. In addition, no government was willing to commit the troop levels that safe areas demanded. NATO and UNPROFOR both estimated that 32,000 troops would be required for Safe Areas. The UN Security Council authorized the deployment of 7,600.

Lesson Learned

18. Grossly insufficient numbers of troops, the absence of agreement on the boundaries of safe areas and the failure to agree their demilitarization were crucial shortcomings of the purely declamatory safe area policy. As Safe Areas were not demilitarized and the presence of the Bosnian Government forces was authorized by UN Resolution 836, they tied down Serb forces and became targets.

Windows of Opportunity

19. In the Spring of 1993 an attempt was made to establish an observation line to follow up and separate the fighting parties where they were at that time. According to some participants, the Vance/Owen plan would not allow this approach, however, and set permanent borders of its own that were non-negotiable. The Vance/Owen plan was thus inflexible and presented itself as a 'take-it-or-leave-it' option. This was one of many missed opportunities.

20. Another window of opportunity had “opened” a few months later with the achievement of bringing the - after substantial Croat and Serb concessions - three parties in Bosnia to accept the Owen/Stoltenberg Plan in September 1993. 1994 was also reckoned to be a window of opportunity for Croatia.

21. The workshop discussed that the failure of the Vance/Owen and the Stoltenberg/Owen plan could be attributed to lack of joint political back-up by major powers - something that Dayton did not lack. In critical situations the political will of the international community had to be backed up by economic, political and military force. With the lacking international support to UNPROFOR in 1993, it should have been evident that a UN Peacekeeping Operation could not perform this role.

22. Some participants wondered if a Dayton-type agreement could have been imposed in 1993 if there had been an unanimous support by the major international players to the Owen/Stoltenberg Plan as it was later given to the Hoolbroke Plan. Different from autumn 1995, the negotiation process was at that time (in 1993) overshadowed by deep disagreements in the EU and between Europe and the United States.

However, it was generally recognized that the important political-strategic shift was created by the political movement of the US in 1995.

17

Preserving the Croat/Muslim Coalition.

23. 23. The Croat/Moslem Federation changed the balance of forces and stopped fighting among themselves. But the federation agreement was a meeting of minds at the top - with differing views at ground level. The prime task was to carry forward the fragile coalition.

Hindrances to Success.

24. The following factors emerged in Workshop discussion as general hindrances to success:

- Control of Weapon Sites. There should have been a common data base and method of counting weapons. In the 4 different UNPAs in Croatia there were 4 different ways of counting weapons.

- Co-Location of Croatian Command. The establishment of Croatian command was a failure because it was incorporated into elements of the UNPROFOR headquarters. It should have been separated.

- Insufficient Planning and Preparation. A SOFA 18 had not been negotiated before deployment, and the mandate had been insufficiently analyzed. UNPROFOR's tasks did not take full account of the situation. The UN imposed territorial separation and took charge of areas. Serbs as well as Croats were happy with the status quo, but the Muslims were claiming sovereignty over BH.

- Differences in Quality of Troops. Parts of the UN Force was neither familiar with the challenging tasks in former Yugoslavia nor sufficiently trained and equipped. It was plain that good quality soldiers, especially trained for peacekeeping and familiar with the conditions in the mission area were required for the tasks described.

General Observations.

Air Power.

25. When air power was used for the purpose of air strikes, UN hostages were taken immediately. This was the case with the incidents in Sarajevo, Gorazde and at the Udbina airfield. By allowing the British out of Gorazde, Mladic lost his potential hostages. All parties tried to gain advantage out of every step the UN took. It was felt that the air-raids should have been proportional and impartial - not unbalancing one of the warring parties.

Humanitarian Relief.

26. Humanitarian relief was a double-edged sword. It also supported the belligerent armies. It was felt by some that aid should have been used as a stick. IFOR, for example, had used international meetings to link their own activities with reconstruction provision.

UNMOs.

27. UNMOs were under UN Command (not to be nationally directed) and could be a source of excellent information for the UN. However, information collected by UNMOs was from time to time slower than the media because UNMOs had to check and re-check the accuracy of their sources. UNMOs had a different political/diplomatic status which made them suitable for use to a wider extent than was normally understood. Confidence building, problem solving and finding practical solutions to a wide range of local issues are typical for successful work of an experienced UNMO.

UNCIVPOL.

28. The periods of January and September 1993 and October/November 1994 were dates long remembered by the CIVPOL who could not operate at more than 30%. From May 1995 onwards, the CIVPOL were not able to operate at all. Only two and a half paragraphs talked about CIVPOL in the mandates - a striking contrast to the Dayton Agreement which had 4 or 5 pages. It was also argued that monitoring was not understood. Problems were caused by those who came in with low ethical standards. It was felt that the UN should go and test monitors in their countries of origin to assess their fitness. It was far better to have 300 qualified monitors than 750 insufficiently trained police personnel.

Joint Commissions.

29. The Joint Commission mechanism established in Bosnia Herzegovina in 1994, 19 working from top to bottom, was a key to the authoritative, effective co-ordination of UNPROFOR activity to re-establish co-operation of the parties.

Window of Opportunity 1995/96

Holbrooke Plan, Dayton and Transition to IFOR

Holbrooke Plan.

30. Although the international community reformed itself, and was now executing a coherent plan for peace, a Workshop participant believed that the situation still represented an early stage of an experiment. Clearly an implementation force became an option because of the previous efforts that had been made. Dayton was therefore a window of opportunity that had been seized, or fallen into, based on the long previous experiment. This window had been created by strategic opportunities, election pressures and the increasing crisis within NATO itself. The Holbrooke plan was a bargained compromise and reflected all the expected contradictions. In some ways it took things back to October 1991. But it included the provisions that US Congress required to approve the deployment. The time may have been ripe on previous occasions, however, and some Workshop participants felt that the opportunity could have been seized earlier.

Holbrooke Plan Concept.

31. One of the main conditions of NATO involvement had been that there was a peace agreement. Prior to Dayton, it was debatable whether there had been a peace to keep much less one to enforce. For Dayton, it was important that the parties freely engaged in the terms and in the territorial settlement of the Peace Agreement. There was a sense in which the environment was 'ripe' for a peace agreement - not only for the international community but for the parties. The parties had to see themselves as gaining from the Agreement. This was a critical part of Mr Holbrooke's and the Contact Group's concept. Based largely on the engagement and power of the US, the parties did sign.

This meant that IFOR was implementing their Peace Agreement, not enforcing an imposed solution on the parties.

32. This distinction underpinned the whole NATO involvement and the IFOR mission, including the one-year duration. It also made NATO's job much simpler than UNPROFOR's ever was, which never enjoyed the benefit of such a solid agreement. As a workshop delegate stated, UNPROFOR never had been the butt of manipulation and had never had the opportunity that IFOR had to use the power of the press to expose the weakness, intransigence and basic dishonesty of life in the Balkans. Now, assisted by IFOR, the civil components of OSCE and the OHR

20

, the parties were themselves responsible for their positions. They now had to develop their own autonomous patterns of cooperation. They had to learn to co-operate and negotiate on their own.

IFOR had aggressively pursued and reinforced this theme of the parties' responsibility to co-operate in its actions and media efforts. In theory, what made the difference between peace enforcement and peace implementation was what made the one-year duration of IFOR feasible. If the parties' commitment to the Peace Agreement was not genuine, the theory would not hold.

33. The current situation on the ground demonstrated solid achievements in inducing such freely-entered patterns of cooperation. The Joint Military Commission 21 mechanism was working. On the civil side, slowly, at the working level, parties were learning to co-operate on some of the technical aspects of reconstruction. Formerly there had been constant reference back to UNPROFOR when too difficult a situation needed to be confronted, manifesting a desire to turn the UN into a scapegoat for the parties' own failures. Now the parties were learning to solve problems themselves. Each achievement made it harder for them to go back to war. It was felt that a genuine desire to reap the benefits of peace could be detected which was very encouraging.

Transition from UNPROFOR to IFOR.

34. June 1995 saw the beginning of a process of change for UNPROFOR and NATO as a team. Military measures, such as the introduction of the RRF 22 , gave indirectly more authority to the Force Commander UNPROFOR.

35. NATO's Operation DELIBERATE FORCE in September 1995 contributed to the change of the military balance between the parties and thus facilitated the October cease-fire, withdrawal of heavy weapons, the re-opening of Sarajevo airport and route to Gorazde. Overall, it was felt that this, in addition to Western political pressure, was an important military-strategic element for success at Dayton.

36. With respect to the implementation of the Dayton Agreement and the transition from UNPROFOR to IFOR, NATO's consensus-building and consultation/decision-making processes had worked well, especially considering its lack of experience with peace operations. Large chunks of BH were now undergoing a transfer of authority agreed upon by the parties in Dayton. By the time of the Workshop 45% of the IPTF 23 had arrived and had been inducted. A great deal of co-operation was evident. The combination of IPTF activity and IFOR's zone of security had proved effective. Not all prisoners had been released - although the parties claimed to have done so.

Prospects for the Future.

37. It was generally felt by the Workshop participants that the Dayton plan would work for two reasons.

- Secondly, the commitment and involvement of the unique authority of the US and undisputed commitments of the major powers, if continued, would make the Dayton plan work.

38. The previous month had seen Carl Bildt, the International Police Task Force (IPTF), politicians and civilians taking over more and more of the Agreement's implementation. After all the Croat, Serb and BiH troops had returned to barracks, the peace process would be able to start in earnest.

Challenges to IFOR.

Compliance.

39. Lack of compliance was a cause for concern, especially as IFOR was beginning to accept Balkan intransigence and delay as a matter of course. IFOR's military tasks were far from over. Difficulty was anticipated in achieving demobilization by D+120 - the time by which movement into cantonment areas had to be done. The lack of a proper infrastructure for the units had created unforeseen problems. There were 900 installations to watch plus many kilometres.

Brcko.

40. The Posavina corridor was also reckoned to constitute a weakness. The Serbs were re-housing a division at Brcko and also moving out their people from Sarajevo.

Post-IFOR Planning.

41. It was felt that IFOR recognized its need to shift its position in order to support the civil side. An ad hoc co-ordination group would be put together to improve work with other elements of the operation. IFOR's biggest difficulty was convincing the local people that stability would continue next year. Reconstruction demanded long-term stability. It was agreed that Post-IFOR planning needed to be conveyed to the people concerned now - otherwise IFOR might be perceived as a band-aid with no long-term end-state in view. A comprehensive package ought to be presented to the Bosnian peoples as a target and incentive for peaceful co-operation.

Negative Signals.

42. There were also negative signals. The Federation was causing major concern for the future perspectives of the Dayton Agreement - as was the distance and self-isolation of the Republik Srpska. It was still not clear that the patterns of cooperation intended by the Peace Agreement would take root.

Return of Refugees.

43. IFOR worked closely with UNHCR. A particular concern was the return of refugees and displaced persons. The possibility of returning to 1991 positions had become something of a dream. NATO was still determined that IFOR would be gone by D+366. It was wondered what Son of IFOR would look like. The Workshop was assured that SHAPE was working on this.

Summary.

44. UNPROFOR and NATO had been able to contribute to the political momentum for the current settlement and peace implementation operation. A strategic lesson might have been that NATO peace implementation should have preceded UN peacekeeping. But such a conclusion was felt to be somewhat naïve. The international community tried to apply the tools it had available during 1991 to 1995, based on what it considered to be politically reasonable levels of commitment at the time. Different tools and levels of commitment failed and the experiment continued.

45. Experimentation had turned out to be costly in human terms. The situation reached the point where the credibility of international institutions and specific nations began to be as much at stake as the actual peace itself.

46. Media coverage of bloody events had affected the integrity of NATO and leading nations. Peace in Bosnia took on dimensions larger than the achievement of peace only. That raising of the stakes and learning from successive experimentation resulted in IFOR.

47. There were significant parallels between IFOR and UNPROFOR. IFOR was conducting a peacekeeping mission. The main difference was the consent of the parties to give IFOR the right, ability and legalization by mandate to implement the Peace Agreement ending a war, while UNPROFOR peacekeepers were sent into an ongoing war in order to gain time for a peace process.

It would be fair to say that former Yugoslavia constituted the most complex peace challenge to date in the post Cold War world, with well-equipped warring factions, leaderships skilled in conducting sophisticated negotiations with neighbouring patron states, but without major strategic consequences for any major Western power. In this situation, experimentation was perhaps inevitable. As a patient, FY was in 1996 no longer in intensive care and could manage to undertake daily tasks. However, it required long-term therapy.

UN Transitional Authority in Eastern Slovenia (UNTAES)

Operations FLASH and STORM.

48. The Croatian army started "Operation FLASH" on 1 May 1995 to forcefully re-integrate the UNPA of Sector West. The operation could have been finished in 4 hours, but UNPROFOR succeeded in gaining time to allow the Serbs living in the UNPA to leave the area. Later, UNPROFOR had the obligation to protect the Serbs who could not escape.

Operation STORM to "re-integrate" the Krajina began on 4 August 1995 after the negotiations in Geneva had collapsed the previous day. The Serbs would not use the word 'reintegration'. An estimated number of 200.000 Krajina Serbs fled, and the UNSC received report about grave violations of human rights and looting of Serbian property in the "newly liberated" areas.

24

Actions took place in Sectors North and South. On 9 August UNPROFOR managed to conclude a truce in Sector North which enabled the Serbs to escape.

50. As a general observation, it was stated at the Workshop, the Vance Plan of 1991 was confounded by the stubbornness of the Krajina Serbs and the impatience of the Croatian side. The UN was therefore always behind the curve.

The present plan agreed upon 12 November 1995 sought to reintegrate Eastern Slovenia into the Republic of Croatia. This had been generally agreed. The Serbs were not really in the mood to fight and realized that there was no other way but to accept and implement this plan. This laid the ground work for the deployment of the UN peacekeeping force in Eastern Slavonia, UNTAES.

25

UNTAES - Introduction.

51. The purpose of UNTAES was to achieve a peaceful reintegration of mostly Serb-populated Eastern Slovenia into the Croatian legal and constitutional system. UN Security Council Resolution 1037 authorized the commitment of a force of up to 5,000 UN troops (Belgian, Russian, Pakistani, Jordanian, Ukrainian and Argentinean) plus civilian police with a Czech hospital and Slovak engineers. The force included 464 UNCIVPOL and 220 civilians including border monitors. The military task was to supervise and facilitate the demilitarization (expected to be voluntary) and to monitor the safe return of displaced persons and refugees to their places of origin. There were approximately 80,000 displaced Croats and 80-100,000 displaced Serbs.

52. The task of the civilian component was to establish a Temporary Police Force, define its structure and size and develop a training programme. The civil component would undertake tasks relating to civil administration and public services in addition to facilitating the return of displaced persons and refugees and co-ordinating plans for the development of economic reconstruction of the region. The first group of 20 Serb and 20 Croat policemen would be trained in Budapest the following week (after 15 April 1996). Neutral uniforms would be used for all together.

UNTAES, Concept of Operation.

53. IFOR would provide a back-up capability, including air support for the purpose of self-defence of the UN peacekeepers in Eastern Slavonia. The Transitional Administrator was basically responsible for governing the region. The Transitional Authority worked through a Transitional Council, including a representative of the Government of Croatia, the local Serbs, the local Croats and other minorities.

54. The Transitional Council was advisory in nature. Its chairman, the Transitional Administrator, had sole executive power. The Transitional Administrator ran a succession of implementation committees to facilitate reintegration and make sure that all plans were in line with Croatia's overall plan for redevelopment and reconstruction. The most important implementation committee was the one on police. The implementation committee on education and culture was also important. It sought to make the Serbs aware of possibilities to improve their situation through co-operation.

55. Other implementation committees included:

- The Public Services implementation committee included a sub-committee on economics, health, agriculture, oil, transport and telephone.

- Other implementation committees were Education and Culture (covering procedures on educational curricula and educational needs for minorities), Return of Refugees and Displaced Persons (co-ordinating their voluntary return - UNHCR was a member of this committee - with a sub-committee on property and compensation addressing ownership questions), Human Rights (covering human rights monitoring - this committee was attempting to link with the Council of Europe human rights bodies), Records (facilitating the location and authentication of records and the issue of licences) and Elections (establishing a timetable and procedures for elections).

- Each committee had representatives from all local minorities. The executive committees, like the Council, were advisory in nature. Tudjman and Milosevic appeared to support this process. The priority was demilitarization - a precondition for the success of all other tasks seeking to achieve normalization.

UNTAES, Supporting Activities.

56. The transitional process was supported by a public awareness campaign conducted through television appearances on local stations, radio shows and daily newspapers within the region. The UN also produced its own newsletters in a variety of languages explaining the aims, mandate and modus operandi of UNTAES. 25,000 copies were produced on a weekly basis. The distribution of newsletters faced opposition from the local authorities because they wanted to conceal the bad news from their people. The people seemed to be war-weary and wanted to get on with normal life.

57. With UNTAES, The UN also had a radio station. Town hall meetings addressed issues of reintegration. Brainstorming sessions on important procedural issues were conducted with the local leadership. A 'door-knocking' programme also took place to establish the mood and concerns of the people amongst the silent majority. 70 households were visited daily while UN civilians and UNCIVPOL mounted patrols throughout 170 villages.

58. In order to improve the ability to fulfill the mandate, UNTAES might improve its performance. UNTAES asked the Council of Europe to help formulate a methodology to conduct a population survey because there was a lack of reliable population data. Unemployment was high and small-scale, quick-impact projects were used to augment economic activity. The key to all these measures underpinning the post-conflict peace building efforts was economic revitalization, and UNTAES had a number of finance projects and schemes.

59. Pledges had been made which in the Spring of 1996 included $9.7 million from USAID, emergency loans from the World Bank, 3,000 housing units for displaced persons from Norway, 5 million Ecu from the EC and demining funds offered from France. UNTAES had also established a comprehensive list of NGOs in the area since they were likely to be key to freedom of movement and their involvement was vital to economic revitalization. A village visitation programme was also undertaken as a pilot project with UNHCR and the Croatian government. It was linked to some early returns of displaced persons.

Prospects.

60. It was believed that UNTAES could make their programme work. The future prospects depend heavily on the sincerity of Croatia and Serbia, however, since any success would have to include both presidents' willingness to support the UN's efforts. It would also decisively depend upon on the preparedness of the parties in Eastern Slavonia to co-operate. There are certain concerns what might happen after UNTAES. Some participants advocated a continued UN presence.

European Perspectives on Conflict Prevention

Introduction.

61. Could the international community have prevented crises from developing into open military confrontation if it had a capacity to act pre-emptively? This question was being addressed by the European Parliament decision to support a crisis prevention project initiated by former French Prime Minister Michel Rocard.

Concerning humanitarian intervention, the right to have access to victims was established in UN Security Council Resolution 43/141. However, the international community had in principle no right to intervene in internal affairs. The experience had several things to teach.

The Difficulties of Response to Crises.

62. Two or three years before Biafra and Somalia exploded, there were plenty of groups who anticipated and explicitly warned against the crisis and urged action. All this documentation was ignored. It could be assumed that none of the people who took the decisions for action would have the capacity (soldiers or finance) to spare. They were unlikely to have anyone in their team who would have studied the situation. Public pressure and the opinion of the last adviser were the main motivators in such situations. The only way to force a decision was to warn of the inevitable consequences of inaction. It was an intellectual problem.

EU Analysis Centre.

63. The proposal for a 'European Union Analysis Centre for Active Crisis Prevention' (in the following: EU Crisis Prevention Centre) before the European Parliament is aimed at early political intervention. Activities of the international community were normally taken by chancellors and foreign policy advisers. Negotiations engaged the reputation and prestige of the ministers or ambassadors concerned. In the EU there was no collective analysis unit.

The proposed EU Crisis Prevention Centre would serve the cause of preventive diplomacy and humanitarian action. In principle, The need for it was widely acknowledged and the international environment indicated its importance. In particular, there was a need to work in conjunction with NGOs, universities, the UN and other organizations.

64. The aim of a EU Crisis Prevention Centre was to change the usual procedures of political decision-making. Political leaders often spend some 70% of their time dealing with the press and would be tired of demands like 'You should do something'. The Crisis Prevention Centre should replace general appeals by substantiated recommendations for preventive action: 'There is this threat and, after appropriate analysis, we think this should be done and it will cost....'

The project also sought to counter the political cost of ignoring warnings. This cost had to be made higher. The project would require the European Parliament President to write to the UN Secretary General and others about crises. If no action was taken, the President of the European Parliament would publish the letter as a kind of warning to respective governments.

Annual Report.

65. The Centre should monitor and 'label' countries according to their performance in the field of human and minority rights. It shall under the auspices of the European Parliament publish an annual report to classify all nations indicating their human rights record, upcoming crises and general international security status. Classifications could be graded as follows:

- Class 1: Sensitivity : Monitor the country and collect information.

- Class 2: Social instability and other tensions.

- Class 3: Alarm or crisis.

- Class 4: Civil War in progress.

- Class 5: Post War re-structuring in progress.

66. The very decision to move a country to a less favourable category of the yearly report should be a signal from Europe to the country in question as well as to investors and foreign political leaders. Diplomatic and economic pressures could also be converged by setting the conditions for e.g. World Bank provisions and other economic and financial conditions. This would impart a cost to states occupying certain categories and motivate states actively to seek promotion to higher categories.

Complementing OSCE and UN.

67. The EU Crisis Prevention Centre should inform and advise the European Parliament and would make information available to other agencies like the OSCE and the UN. It was intended to complement existing bodies handling crises and -armed- conflict, rather than to replace them. Its strength could be:

- to raise the awareness of political decision-makers, and

- to recommend co-ordinated measures to be implemented.

Preventive Diplomacy and Preventive Deployment --

Lessons Learned from Macedonia

Course of Events.

68. As early as September 1988, a Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister advanced the general notion of a preventive military force with UN observers. This proposal anticipated the preventive UN peacekeeping operation which was requested by the President of the former Republic of Macedonia in a letter to the UN Secretary-General on 11 November 1992 in order to monitor its troubled borders with Serbia and Albania and avoid spreading the conflict in other parts of former Yugoslavia to the area. After recommendation by the chairmen of ICFY 26 , Vance and Owen, the UN Security Council authorized the establishment of UNPROFOR presence (FYROM 27 Command) in Macedonia on 11 December 1992.

69. The only mission of its kind in UN peacekeeping history, became an operation independent from UNPROFOR in February 1995 with a force commander and an SRSG and was renamed into UNPREDEP (United Nations Preventive Deployment Force).

The original size of the force deployed was 1,200. Its mandate was to monitor and report all developments that could undermine Macedonia's security. The host nation had invited the UN to initiate the operation and the government had been very co-operative and helpful at all times.

70. The interests and capacities of neighbouring countries never exceeded the deterrent capacity of the UN presence. The fact that Albania was too weak and poor and that the FRY was too busy elsewhere kept the situation relatively calm. FRY 28 also wished to get the UN sanctions lifted which kept them quiet. UNPREDEP possessed no mandate for the Bulgarian and Greek borders, but other factors restrained those countries from military action.

71. The Northern border of Macedonia was without demarcation and disputed in many areas. The parties had shown force and tested the limits when exercising, patrolling and flying in the border area by crossing, hostile shouting, pointing weapons, digging trenches and detaining patrols of the opposite side. The most serious situation occurred in Summer 1994 when a considerable number of soldiers opposed each other in the Cupino Brdo area in North-Eastern Macedonia. Without the UN presence and mediation the situation would probably have escalated into open hostilities. This was also the view that senior representatives of both parties had revealed in informal discussions.

There was much illegal traffic on the Albanian border - mainly linked to organized crime. Several shooting incidents, causing fatal casualties had occurred. Ethnic unrest inside Macedonia had led to open riots in February 1995 in the Tetovo area, leaving one dead and eleven wounded.

Factors for Success.

72. Although UNPREDEP was the first preventive peacekeeping mission, and was deployed on unilateral request and consent of the host country only, it could be described as traditional by means and methods. Peacekeeping techniques learned in earlier missions were valid. Significant amongst the factors contributing to success has been correct timing, a clear and feasible mandate and the consent of the host nation.

73. Operational elements of success in this kind of environment included

- good personal relations with all parties and at all levels,

- immediate reaction to incidents at a local level before the situation escalated

- and a readiness to raise issues at a higher level if necessary,

- troop readiness, reserves, good discipline and politeness, special peacekeeping training in addition to basic military training, also selecting people with the right attitude and screening out the 'Rambos', and strict impartiality.

US-Nordic co-operation.

74. The mix of participating nations also favoured success: The considerable political and military weight of the US presence had been of especial significance. The great experience of Nordic states in peacekeeping had also successfully balanced the UN presence in the area. Many US representatives admitted today that they had learned a lot and that they had a better understanding of traditional peacekeeping after two years of serving with the Nordics in Macedonia. The cooperation between the UN and Nordic battalions could only be described as excellent. Very useful exchange programmes of soldiers and joint exercises had taken place.

Other factors of success.

75. However, other factors also contributed to the absence of conflict in Macedonia including:

- international sanctions against Serbia,

- the work of international agencies (such as the OSCE, ICFY, UNHCR and others),

- relatively moderate behaviour by Macedonia's neighbours (who were not helping - but also not threatening military action), and

- Macedonia's attempts to maintain and encourage a viable multi-ethnic society.

76. All of these factors were important. Stability was enhanced, however, by the unanimous UN commitment, i.e. the undisputed support by major nations. It focused international and regional attention on Macedonia, thus moderating internal and international political friction. Presence alone was a powerful element of prevention. UNPREDEP demonstrated to regional parties that the continued peaceful existence of the Republic of Macedonia enjoyed international support. The presence of a respected international agency as a source of accurate information moderated destabilizing words and activities. Although the media took little interest in 'calm and quiet' situations, yet the UN commitment served to focus international attention on Macedonia's potential crisis.

Monitoring.

77. Monitoring contributed to de-escalation by correcting wrong risk assessment. The UN-hosted international meetings served to provide an objective political-military analysis of the situation - the importance of which could not be overstated. UNPREDEP also regularly monitored the military, political, economic and social situation - enabling it to confirm, counter or balance the reporting of other agencies.

78. For example, in 1994 the US State Department identified as a significant risk the potential for a mass exodus of ethnic Albanian refugees from the Kosovo region in Serbia through Macedonia to the Greek border, threatening conflict between Greece and Turkey. However, UNPREDEP concluded that the risk was low, submitting its assessments regularly to UNPROFOR and the US and Nordic governments through their unit national chains of command and to visitors. A second example was the belief held by some experienced journalists in March 1995 that military tension in the Southern Balkans was high and that a number of Serb units were 'massed against the border'. UNPREDEP was able to report that there were none.

Settlement of Border Disputes.

79. UNPREDEP's border identification and verification helped stabilize the region. Macedonia's boundary with Serbia had long been disputed. Initially the Macedonians and Serbs refused to co-operate with the UN commander's requests for border data. Promising secrecy, the commander and his staff obtained and used the differing border traces to propose an administrative UN boundary - at first called the 'Northern Limit of the Area Of Operations' (NLAOO), but now called the 'UN Line'.

In July 1994, both parties accepted this boundary as the Northern limit of UN patrolling. Macedonian and Serbian patrols also tended to respect the boundary, indicating that the UN solution to this practical problem established a de facto buffer between potentially hostile parties.

UN Commanders as Active Peacemakers.

80. As in traditional PKOs, notably in the Middle East, the commander in the field played the role of the diplomat. This can be seen as the irony of the preventive deployment which was perceived by the local government like a military deterrent rather than a politically active mediator.

The UN Force Commander established early contact with the Serbian General Staff in Belgrade. His broad interpretation of the preventive mandate allowed him to clarify the UN's mission with all parties, thus exercising the traditional peacekeeping principle of transparency. The Macedonian government complained about this, highlighting the potential problem of a host nation claiming 'ownership' of a preventive force. Nevertheless, meetings began in March 1994, thus enabling the UN Force Commander to settle border conflicts before they could escalate:

81. Initial visits uncovered Serbian suspicions that the UN force, especially its US battalion, foreshadowed a major deployment of US and NATO forces. The commander's personal diplomacy, bolstered considerably by a generous sharing of information turned Serb suspicion into trust and established a UN bridge of communication between the two governments. For example, in October 1994, the UN Force Commander, General Tellefsen, carried to Belgrade the good wishes of the Macedonian Minister of Defence and the Chief of Staff of the Macedonian armed forces. He reported UN monitoring in the border region, explained plans for the December rotation of a new US infantry battalion, and delivered a map of the UN deployment with all unit headquarters and observation posts plotted.

82. In return, the Serbian general reported plans to shift border units and described the state of their preparations for border commission work. He also sent his good wishes to his Macedonian counterparts. These visits bore fruit almost immediately. After only two visits, in June and July of 1994, a dangerous military confrontation in the US sector between Serbia and Macedonia was defused when the UN commander intervened, brought both General Staffs to the area and mediated a Serbian withdrawal from an incursion into Macedonia. Had the UN not been present, the confrontation could have escalated.

Despite of their initial resistance, military leaders in both governments found in UNPREDEP a reliable, neutral, non-confrontational form of communication. The UN contact confirmed non-hostile intent, finessed the lack of diplomatic recognition between governments and lessened the chances of destabilizing confrontation. In March 1995, General Engström began visits to Albanian officials. The commander now regularly travelled to both Belgrade and Tirana.

'Unilateral' Consent

83. The UN command in Macedonia used traditional peacekeeping principles and structures. But the preventive deployment in Macedonia did not require the consent of other parties than the host government prior to the deployment. The UN had to create consent with the other parties in order to prove its impartial role.

Essentially, the UN commander developed his own consent with the Serbs and Albanians by acting in an even-handed manner to overcome perceptions of partiality of the UN force. Parties in Macedonia who were being deterred and who did not consent to the deployment viewed it with suspicion. Both Albania and Serbia perceived the UN to be partial in its deterrent posture.

The success of the UN force in negotiating an end to the confrontation crisis in the US sector and the simultaneous acceptance by the parties of the UN boundary was the happy ending to a major problem that might be typical of preventive deployments. Through a wide and flexible interpretation of the mandate, the UN Commander created consent in a crisis situation. Another commander with a more cautious approach or less experience in UN Peacekeeping might not have been successful.

Further Observations.

84. The mandate was written down in a clear way - but allowed flexibility to commanders. It was a positive advantage for the commander to be distanced from superior headquarters. The force was deployed on time and was a correct proactive action. This allowed freedom of action from the beginning and before anything serious happened.

85. UNPREDEP did not meet standards for high -technology stand-off surveillance. Soldiers monitored with binoculars and foot patrols. UNPREDEP's blended approach performed a new mission with an 'old' peacekeeping force structure, deployed in due time to prevent detoriation of the situation.

86. The structure of the force was almost ideal and had been put together by experienced Nordic officers. 600 US soldiers represented an important symbolic asset. The combination of US/Nordic in this way was useful. The fact that the commander was a Nordic Brigadier-General sent the signal that this was a UN, not US, operation.

87. Freedom of action allowed the establishment of dialogue with the parties in the area. UNPREDEP facilitated dialogue between the Macedonian and Serbian governments. This dialogue fostered trust between the leaders. There was still a need for a UN presence in Macedonia. The current problems mirror to some extent those problems which had existed in 1993.

Scope for Improvement - Lessons Learned.

88. Macedonia was far from the conflict in FY and especially distant from the joint headquarters in Zagreb. Consequently, UNPREDEP's higher headquarters did not have the time to take a close interest. This, combined with a long supply route led to a slow and ineffective response to UNPREDEP's needs. Some Workshop delegates said that much procurement could have been made more quickly and cheaply from local or closer markets.

89. It would have been better if UNPREDEP had been separated earlier from UNPROFOR's organization. This would have prevented administrative difficulties. Such separation was the wish of the host government from 1994. UNPREDEP as an independent mission would have underlined the fact that Macedonia was not a party to the Yugoslav war.

National Lines of Command.

90. The unique system of the US chain of command was also to a certain extent a hindrance to smooth operation. The US battalion commander was in a difficult position, receiving orders not only from his UN commander but also through national channels.

The US battalion had several national restrictions that prevented it acting in concert with the other battalion sometimes. The only restriction left today for US troops was that they could not go closer than 300 metres to the UN line. This last restriction was not lifted because it was not seen as hindering the fulfilment of the mission. But Macedonia is a very mountainous country and ridges often obscured the view. Therefore there were times when the line had to be approached more closely. The US battalion was thus hindered from fulfilling the same tasks as its sister battalion. If a government decided to take part in a UN mission, the same rules and restrictions should apply throughout the whole mission.

Long-term assessment.

91. Long-term overall assessments is still to be made - but military assessments could be made now: Since the establishment of UNPREDEP a lot of emphasis had been put on social, economic, and humanitarian developments. Things could have escalated in Macedonia on many occasions - but never did so due to a variety of mediation efforts by the UN.

The situation on the FRY border today is much calmer. Border incidents had almost ceased. UNPREDEP had negotiated an administrative boundary, called the Northern Limit of Area Of Operations (NLAOO), later amended and renamed the 'UN line'. Although the line was not agreed by the parties as an official border, a 'gentleman's agreement' had been reached to use it as a patrolling line and to be tolerant in the border area.

92. Around the dominating hill massif of Cupino Brdo there was a UN-controlled, de-militarized buffer zone. Since Autumn 1995, meetings at working level between UNPREDEP and the FRY authorities had been accepted by the FRY General Staff. Such meetings were routine today. Before recognition, the Macedonians did not participate in the meetings. There were also regular border meetings at working level at the Albanian border - meetings in which the Macedonians took part.

93. Since the ethnic riots in Tetovo, the government had been forced to change its legislation in order to give better rights to minorities. Some tension still existed. close co-operation of UNPREDEP, CivPol and the OSCE was very helpful to improve the situation of minorities in Macedonia.

94. UNPREDEP also provided much humanitarian assistance in its area of operation. This included medical aid, transportation, assistance with water supplies and communication techniques, road-repairing, snow-ploughing and distributing Red Cross aid. These activities, and a well conceived media campaign of UNPREDEP in co-operation with local media helped to preserve good relations with the local population.

Concluding Observations.

95. There is no doubt that UNPREDEP is a very encouraging success for the United Nations. It found itself in the middle of debates about peacekeeping versus peace enforcement. War in the Southern Balkans would have been a catastrophe that could be ill-afforded. Had the FRY wished to attack and occupy Macedonia it could easily have been done militarily. However, the disadvantages and risks were too great.

The Way Ahead.

96. UNPREDEP probably requires two more years to complete its task. The Kosovo issue needed to be solved before the UN left the area. Mutual recognition of borders was necessary before withdrawal could take place. The establishment of a mutually-agreed border between Albania and Serbia we would help provide a solution to the Kosovo problem.

Lessons Learned from Questionnaires --

Opinion Survey among UN Personnel

Survey concept.

97. The multifunctional character of peacekeeping missions highlighted the enormous challenge the UN was facing in practical terms regarding the practicability and applicability of peacekeeping as a possible method of UN intervention in civil war-like conflicts:

- How are the principles interrelated to each-other in the everyday experience of peacekeepers?

- What is realistic for UN peacekeeping to achieve in the dynamic reality of 'unstable conflicts'?

98. To answer these principle questions on peacekeeping in 'new conflicts', DANORP started with a traditional approach of qualitative research like the evaluation of literature and individual open interviews with key personnel.

It soon became apparent that this method was not sufficient to provide comparable data and information if empirical conclusions for future UN operations should be drawn. Most interviewees gave very interesting answers, but their views were partly contradictory and not necessarily representative.

99. It was therefore decided to complement the qualitative research by quantitative survey methods, i.e. by means of a 'lessons learned' questionnaire among practitioners. They serve as one of the best resources to verify the practicability of mandates, principles and methods in a UN operation. DANORP sought to utilize their knowledge in order to get a representative overview about their experiences and lessons learned.

100. DANORP tested and developed, in co-operation with experienced UN peacekeepers, the UNPROFOR questionnaire. FAFO, a Norwegian institute with experience in international surveys and the Danish Armed Forces Centre of Leadership in Copenhagen, assisted in design and survey methodology. Staff of Defence Commands, Defence Ministries and UNPROFOR assisted with distribution and collection of the questionnaires distributed mainly among officers having served in former Yugoslavia.

Methodology.

101. The questionnaire survey became an important tool of the project. The quantitative (statistical) analysis of views expressed by UN personnel about their 'lessons learned' should help to verify findings from UN commander workshops, open interviews with key personnel, official reports, research or public statements.

The Project sought to concentrate on practical, operational aspects and discover reasons accounting for success in order to make practicable recommendations to improve UN operations.

The first survey was to be seen as a pilot project which did not necessarily fulfil all the criteria of a statistical representative survey. The distribution was done randomly and the methodological system (eg return control) was not fully developed. The response rate from most countries was very high (up to 80%). Background figures like age, nationality and rank would allow a closer representativity assessment.

A graphical record of some of the Project's preliminary findings is attached in Annex A.

Findings.

102. In January 1995, in his revision of the 'Agenda for Peace' the UN Secretary General reported to the Security Council that “'analysis of recent successes and failures showed that in all successes the classic peacekeeping principles of impartiality, consent and the use of force in self-defence had been respected. In most of the less successful operations one or other of such principles had not been respected”.

He went on to state that “the logic of peacekeeping flowed from political and military premises that were quite distinctive from those of enforcement and that the dynamics of the latter were incompatible with the political process that peacekeeping was intended to facilitate.”

29

By means of the questionnaire survey the project had vindicated the UN Secretary General's views.

103. Several first-hand findings emerged illustrating trends relating to key issues of peacekeeping in Former Yugoslavia. Significant findings from a sample of 589 30 UN officers included the following opinions:

Handling Peacekeeping Principles.

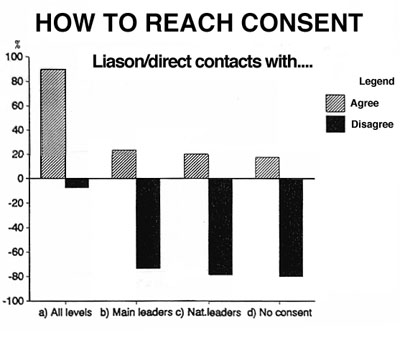

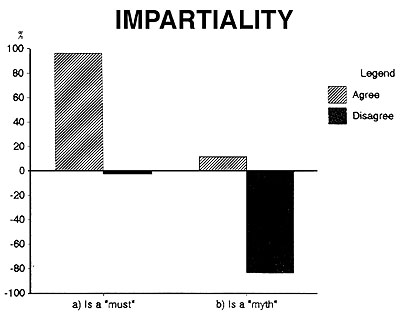

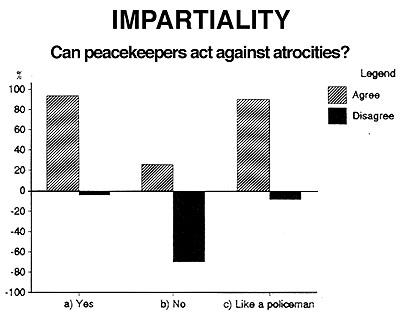

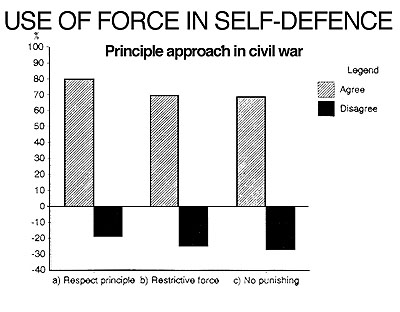

104. The Principle of Consent: