|

|

|

|

CIAO DATE: 12/03

Searching for Sense in the Tax Cut Debate

Charles W. Calomiris and Kevin A. Hassett

On The Issues

December 2001

Long-term tax cuts have fallen out of favor because critics claim that they will lead to higher interest rates. But the evidence of both economic scholarship and recent history refute that claim. The long-term tax cuts under consideration in Congress will result in moderate deficit increases, and moderate increases have little or no effect on interest rates.

In response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, Congress and the Bush administration have considered alternative tax cut proposals to bolster the economy at a vulnerable moment. Opposing voices question which kinds of tax cuts would work best, how large the cuts should be, and whether they should be temporary or permanent. Unsurprisingly, politics has dominated economics in the debate. The controversy is generally a predictable political one between Democrats wanting to preserve room to spend more in the future and Republicans trying to return tax dollars to their source. But even the economic experts shaping the debate are not displaying serious economic thinking about tax cuts.

A consensus seems to be emerging that tax cuts should be small (in the neighborhood of $30–$60 billion) and temporary. For years, economists have pointed out that long-term tax cuts, if properly designed, more successfully stimulate growth (more on this later), but that viewpoint has fallen out of favor. According to the ostensible economic reasoning in favor of small, short-term tax cuts (advocated with special verve by Sen. Jon Corzine of New Jersey and Citicorp vice chairman Robert Rubin), larger or more permanent cuts would increase government debt, spur increases in long-term interest rates, and reduce investment. Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan's comments have lent credibility to that argument. Even President Bush and his advisers have voiced concern about the risk of boosting deficits to the point where counterproductive interest-rate hikes could result.

Support from Studies?

Given the importance of getting policy right in the current economic environment, and given the strong statements of Rubin and Corzine, one would expect careful economic analyses supporting those positions about the reactions of interest rates to moderate increases in deficits. But no such studies exist. To the contrary, every recent study published on that topic has failed to link moderate increases in deficits with increases in interest rates. As Paul Evans of Ohio State University has shown in his careful studies (1985, 1987a, 1987b) of links between deficits and interest rates in several countries, even the major deficits produced by wartime spending had no discernible effect on long-term interest rates. Other studies published since his have reached similar conclusions.

Those facts do not surprise economists for several reasons. First, as Harvard's Robert Barro has pointed out for decades (and as the great classical economist David Ricardo noted first), forward-looking taxpayers should at least partly offset government deficits with private savings if they anticipate increases in future taxes to repay the new debt. Perhaps more important, when open international capital markets allow countries to draw on each other's savings, small increases in one country's debt will be offset by savings pulled into that country from abroad, with barely changed interest rates.

Furthermore, increased private savings, domestic or foreign, may not be necessary to prevent interest rates from rising if the central bank, rather than the public, can absorb the growth in government debt without spurring inflation. In a growing economy, a central bank can do that so long as the growth of government debt does not outstrip the real growth rate of the economy. (In the early 1980s, several papers—perhaps most clearly one by Carnegie Mellon's Bennett McCallum in 1984—established the logic of this link.) As recently as early September, Fed officials and many economists were concerned that the supply of bonds available for Fed purchases would dry up. The Fed requested special new authority from Congress to purchase corporate bonds. Clearly, substantial room exists to expand the supply of government bonds that the Fed can absorb in the future without spurring inflation.

McCallum's growth condition essentially defines what is meant by a moderate deficit. If persistent deficits lead to permanent growth in government debt in excess of the real growth rate of the economy, there is no alternative to inflationary money creation to repay the growing debt. Such money creation and inflation will be anticipated and will thereby produce immediate increases in long-term interest rates. But so long as debt grows at a slower rate, it will be absorbed into the growing balance sheet of the central bank and thus pose no threat to nominal interest rates.

Debt growth that exceeded moderate deficits and forced inflation higher would affect real interest rates (that is, the real cost of borrowing, defined as the difference between nominal interest rates and expected inflation). Real interest rates are the more relevant variable in investment decisions since borrowers' incomes tend to rise with inflation. But if inflation pushed up nominal rates, real interest rates would also be affected if inflationary uncertainty were a byproduct of higher inflation (as tends to be the case). Thus "immoderate" debt growth would adversely affect real interest rates, with an implicit threat to investment from immoderate deficits. Other effects from inflation on investment could either offset or reinforce the effect of inflationary uncertainty on real interest rates. 1

In summary, moderate growth in government debt—whether "monetized" by the Fed or held by the public—will likely have little or no effect on interest rates and the cost of investing. First, compensating increases in domestic savings partly offset new government debt offerings. Second, any upward pressure on interest rates is diffused over the entire global capital market, which can absorb increased debt with much less impact on interest rates than the domestic capital market alone can. Finally, the need to grow the money supply alongside real growth in the economy also implies a substantial capacity to grow government debt without increasing the amount of debt held by the public and thus avoiding upward pressure on interest rates.

Real Interest Rates and Deficits

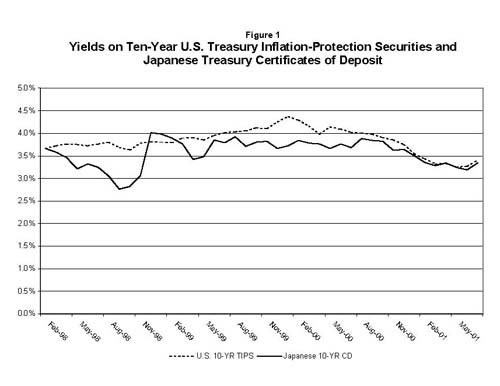

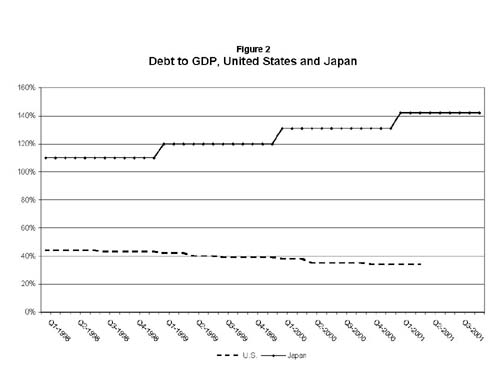

What do facts and logic tell us about the recent and future association between interest rates and moderate increases in deficits? What are the implications for tax policy today? Figure 1 plots real interest rates on ten-year government debt for the United States and Japan; figure 2 shows the debt-to-GDP ratios of the two countries for the past three years. The most striking aspect of the diagrams is the similarity between the levels of real interest rates in Japan and the United States and their trends, despite the different histories of debt-to-GDP ratios in the two countries. The main conclusion to be drawn from the diagrams is clear: Despite a substantial decline in U.S. debt-to-GDP ratios during the period and a simultaneous substantial increase in Japanese debt-to-GDP ratios, long-term real rates have remained essentially the same in the two countries and have tracked each other closely. In today's world of open capital markets, such a result is not surprising.

Nevertheless, in light of recent statements by Rubin and Corzine, those facts merit emphasis. Great changes in deficits, up or down, have not mattered for interest rates. Figures 1 and 2 are not a formal statistical test of the effects of rising domestic debt on interest rates. A more complete analysis would take account of other influences on interest rates in each country. At the same time the figures do make our basic point. It would be hard to believe that domestic deficits or surpluses in the two countries had important effects on real interest rates that are hidden because of coincidental, exactly offsetting domestic influences in each country that reduced real interest rates in Japan and raised them in the United States. 2

Prospectively the policy question of interest is how much capacity exists for increasing U.S. government debt without affecting interest rates. Congressional policymakers are considering temporary tax cut proposals that would amount to less than $100 billion in increased debt (statically scored) over the next three years, on top of emergency expenditures on airline support and disaster relief of roughly half that amount. A temporary $100 billion tax cut amounts to less than 1 percent of GDP, which when added to emergency expenditures would result in extra debt offerings of roughly 1.5 percent of GDP. Figure 1 shows that reductions in U.S. debt from 44.5 percent of GDP to 33.9 percent over the past few years had no perceptible effect on interest rates. Thus, there is most likely room for a tax cut of much greater size than 1 percent of GDP without threatening to raise real interest rates. Furthermore, only a matter of weeks has passed since the Fed appealed to Congress for new powers to purchase debts other than government bonds so that the scant future supply of government debt would not constrain money growth.

Existing government debt capacity can permit substantial tax cuts well beyond those contemplated by Congress without threatening to raise long-term interest rates. Congress should consider permanent rather than temporary tax cuts, particularly in the corporate tax rate, in light of the importance of addressing current macroeconomic risk and in the absence of any threat to interest rates from such a tax cut.

The Need for Permanent Change

Which tax cuts would be most effective for boosting economic growth? Tax policy should focus on layoffs and investment expenditures since the current recession is an investment-led decline in which a sharp contraction of expenditures and the potential for ever-growing layoffs are the main problems. Although many tax cuts targeted toward consumers are potentially useful (for example, expanding unemployment insurance would likely spur consumption), consumers without job security are unlikely to spend our way to recovery. The cure to the current recession must address the threat directly, and the measure of the relative effectiveness of prospective tax policies should be their likely immediate impact on investment and jobs. Thus tax cuts must focus on permanent changes in marginal tax rates for individuals and for corporations. Temporary tax cuts are motivated by a fear that interest rate movements might offset a tax stimulus. If no such movements are likely, then the best possible tax stimulus should be chosen. Temporary tax cuts cause significant distortions, both across time and among assets. Without an interest rate justification, the introduction of such distortions is senseless. Only permanent changes in corporate and individual tax rates can lead to immediate, and persistent, large increases in investment and job creation.

What types of permanent tax cuts are most advisable? We specifically favor a substantial, permanent reduction in the corporate tax rate (say, from 35 percent down to 25 percent). That cut would spur immediate recovery and sustainable long-term growth through two channels. First, it would permanently lower the capital costs for the purchase of new investments and raise the desired capacity of American firms. Those circumstances would immediately boost investment activity. Second, the reduction would lead to a sharp stock market rally, which would prompt a modest but significant increase in consumption activity that normally accompanies stock market advances. Even a tiny propensity to consume increased wealth could provide a consumption stimulus to GDP of more than one percentage point per year.

The lost revenue from the suggested tax cut would be scored at $60 billion a year, although appropriate dynamic scoring would imply a much lower number (perhaps half that amount). Nevertheless, existing debt capacity can easily support the reduction in revenue without any consequences for interest rates, even under the conservative static scoring assumptions of a $60 billion annual cost. The growth in Fed money alone would absorb a substantial chunk of new debt. Assume conservatively that static scoring is accurate, that real economic growth will average 3 percent, and that inflation will average 2.5 percent. The Fed holds more than half a trillion dollars in government debt. If money growth keeps pace with nominal economic growth of 5.5 percent, Fed purchases of government debt would absorb roughly half the future debt resulting from our proposed permanent corporate tax cut. The remaining amount would be a trivial addition to the global public holdings of government debt.

There is little risk right now of overheating in the short run from a tax cut—or of boosting interest rates in the long term. There is a much greater risk in doing nothing. A tax cut geared to boosting stock prices and stopping layoffs is just the medicine needed to forestall a lengthy recession. Not only would a substantial tax break have immediate pecuniary consequences for corporations and consumers, it would provide a confidence-boosting signal of government resolve and bipartisanship at this crucial moment.

References

Cohen, Darrell, Kevin A. Hassett, and R. Glenn Hubbard. 1999. "Inflation and the User Cost of Capital: Does Inflation Still Matter?" In The Costs and Benefits of Price Stability, edited by M. Feldstein. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 199–234.

Evans, Paul. 1985. "Do Large Deficits Produce High Interest Rates?" American Economic Review 75 (March): 68–87.

1987a. "Interest Rates and Expected Future Budget Deficits in the United States." Journal of Political Economy 95 (February): 34–58.

1987b. "Do Budget Deficits Raise Nominal Interest Rates? Evidence from Six Countries." Journal of Monetary Economics 20 (September): 281–300.

Feldstein, Martin, ed. 1999. The Costs and Benefits of Price Stability. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Endnotes

Note 1: Offsetting effects include the so-called Mundell-Tobin effect (encouraging investment in real assets to avoid inflation taxation) and tax-related effects through which inflation can reduce after-tax interest rates (Cohen, Hassett, and Hubbard 1999). Conversely, inflation can reduce the benefits of depreciation. For a more thorough discussion, see Feldstein 1999.

To measure long-term real interest rates for the United States, we use inflation-indexed, ten-year U.S. Treasury debt. Our method avoids the need to estimate expected inflation and subtract it from observed nominal yields. Another advantage of using indexed Treasury debt is that doing so abstracts from extreme time variation in the special liquidity premium enjoyed by nonindexed U.S. debt (the short-term demand that can be importantly affected by international flights to dollar-denominated high-quality assets, as after August 1998). Back

Note 2: We construct real yields for Japan by assuming a constant rate of expected inflation, which we set equal to 2 percent throughout the period. Our method requires some judgment about the unobserved expected ten-year inflation rate (the time period relevant for measuring real yields on ten-year debt). Actual inflation rates during the period differ greatly in Japan according to which price index one chooses; Bank of Japan studies have argued that true deflation has be&-;en higher than measured deflation in recent years as a result of flaws in price indexes. The consensus view of the recent experience is that actual deflation has been roughly 2 percent for recent years. In any case, future expected inflation or deflation over a ten-year period may differ from past inflation or deflation. Indeed long-term inflation expectations may have increased slightly in Japan in recent months, as some analysts have recently been forecasting policy changes at the Bank of Japan that would bring an end to deflation and there has been widespread discussion of targeting a zero inflation rate. Other analysts believe that the deflationary trend will continue. Our assumption of a constant 2 percent deflation rate for the period is a conservative estimate for our purposes. It is conservative because our purpose is to show that real Japanese interest rates have not risen in response to increased Japanese deficits. By assuming constant deflation (rather than assuming a decline in expected deflation in recent months), we bias the data against making our point. Back

Charles W. Calomiris and Kevin A. Hassett are, respectively, a visiting scholar and a resident scholar at AEI.