|

|

|

|

Political Science Quarterly

Volume 114 No. 3 (Fall 1999)

Israel’s National Security and the Myth of Exceptionalism

By Gil Merom

*

GIL MEROM is assistant professor in the Department of Political Science, Tel-Aviv University, and a U2000 Fellow in the Department of Government and Public Administration, Sydney University. His most recent articles include “Strong Powers in Small Wars: The Unnoticed Foundations of Success,” and “A ‘Grand Design’? Charles de Gaulle and the End of the Algerian War.”

Members of social groups tend to develop their sense of collective identity on the basis of two kinds of perceptions: perceptions of shared attributes within the group, and perceptions of the difference between these attributes and those of other social groups. 1 Images of identity and difference, irrespective of whether they are inherent, imagined, or acquired, serve as the glue that bonds individuals into an imagined social whole. They also serve as the foundations of a sense of exceptionalism, which is pivotal in the formation and molding of religious, ethnic, and national communities, and often serve the latter for years thereafter. The British people, for example, prided themselves in the seventeenth century for being exceptionally rational and scientific, and the Americans still believe today that they are inspired by an exceptional idealist creed. 2

A sense of exceptionalism may also serve collectives, the modern nation-state included, in other instrumental ways. When married to power, a notion of exceptionalism may generate aggression and violence. National communities that became powerful often convinced themselves that their success was proof that they were culturally or otherwise exceptional, and thus entitled or even ordained to become agents of global acculturation. Moreover, in their sense of exceptionalism, they discovered a means to justify a gluttonous celebration of empire building and exploitation. Underdogs’ sense of exceptionalism is somewhat different. Usually it combines inferiority and superiority complexes. In addition to an inherent sense of distinction, it includes a sense of exceptional vulnerability. This mixture can at times serve a nation well, but it can also become a burden.

In this article I assess the claim, which is prevalent in Israel and is often accepted elsewhere, that Israel’s national security is exceptional. I first discuss the sources of the Israeli belief in exceptionalism. Second, I review various elements in the Israeli image of national security exceptionalism and their consequences. Third, I subject the realities of Israeli national security to a comparative scrutiny, discussing in particular the issues of threat and morality of conduct. Finally, I conclude with a discussion of the consequences and risks involved in perceiving Israeli national security in exceptional terms.

Before I proceed, however, a brief clarification is necessary. My argument about Israel may remind readers of Jack Snyder’s discussion in Myths of Empires. 3 Snyder’s argument is that empires overestimate the aggressive propensities of enemies and at the same time depict them as paper tigers. These myths of empires, which present expansion as both essential and inexpensively obtainable, are created and propagated by factions and institutions that seek to promote parochial interests. I argue that Israel displays a somewhat similar combination of excessive fears and self-confidence that Snyder describes. Whereas Snyder’s thesis is primarily instrumental, mine is primarily cultural. I attribute the Israeli mythology of exceptionalism to deep-rooted beliefs that are widely shared and as such conceive of it as a by-product of cultural and historical processes. 4 In short, I consider the Israeli interpretation of reality as fundamentally spontaneous or organic, though I admit that on occasions it has been used instrumentally.

The Sources of the Israeli Image of Exceptionalism

A significant part of Israeli society and leaders is convinced that the Jewish and Israeli people, their historical experience, and the security problems they face are exceptional. These perceptions of exceptionalism rest on cultural, historical, and strategic foundations.

The origin of the cultural foundations of exceptionalism are in Biblical notions that depict the Jewish people as divinely “chosen” (am nivchar). Such ideas are relatively widespread in Israel, because most Israelis were educated to think so and because most of them believe in the main tenets of Judaism. 5 The association between religious beliefs and the notion of exceptionalism takes many shapes and forms. For example, Gideon Ezra—a nonobservant parliament member from the Likud party and a former senior officer of the General Security Service (GSS)—believes in God, because “only God could have created a people so special as the Jewish people.” 6 The cultural perception of Jewish exceptionalism is also expressed in secular terms. David Ben-Gurion, the founding father of modern Israel, was never tired of making the point of Jewish distinction. In one of his speeches in 1950 he explained: “We are perhaps the only ‘non-conformist’ people in the world. . . . We do not fit the general pattern of humanity: Others say because we are flawed. I think [it is] because the general pattern is flawed, and we neither accept it nor adapt to it. . . .” 7

The sense of inherent exceptionalism, which emanates from concepts such as the chosen people, also includes the belief that the Jews would become a “light unto the nations” (or la’goyim) or a beacon to the world. Again, the words of Ben-Gurion illustrate how such deep-rooted religious concepts were incorporated into the modern secular-nationalist creed of Israelis. While Ben-Gurion emphasized that the Israelis wanted “to be like all gentiles,” he hastened to add that they also aspired “to be different from the rest of the world in [their] spiritual superiority. . . .” 8 Similarly, in a speech he delivered to Israeli youths, he masterly meshed the theme of moral exceptionalism with the idea of inherent national security exceptionalism: “You . . . know that we were always a small people, always surrounded by big nations with whom we engaged in a struggle, political as well as spiritual; that we created things that they did not accept; that we were exceptional. . . . Our survival-secret during these thousands of years . . . has one source: Our supreme quality, our intellectual and moral advantage, which singles us out even today, as it did throughout the generations.” 9

Now, while the image of inherent spiritual exceptionalism that we have reviewed this far is manifestly positive, it sometimes also acquires a negative dimension that depicts the Jewish people as wanting essential spiritual qualities as a result of a long life in a nationally-degenerating Diaspora environment. For example, Joseph Doriel finds that the Jewish strategic choice of “a method of survival rather than of expansion . . . left the Jews . . . with a biological programming that became obsolete—endangering their functioning in [their effort] to achieve collective national security under the new conditions . . .” 10 This perception of Diaspora-born weakness was part of the belief system of Zionist leaders, long before Doriel defined it so crudely. It was partly responsible for the idea that Israel, and particularly the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), must become a melting pot for the purpose of molding a new nation that will erase not only the differences between the various Jewish communities, but also the weaknesses the Jews have acquired in Diaspora life. 11

The historical foundations of the Israeli perception of exceptionalism contain references to ancient national calamities and the presumably bitter experience of Diaspora life at the mercy of Gentiles and anti-Semitism. These foundations give rise to an acute sense of solitude and abandonment. Historical events both acquire meaning from and help to shape the cultural foundation of Israeli exceptionalism. Thus, the historical experience of isolation is bolstered by the belief that the Jewish people was preordained to “dwell in loneness” (am levadad yishkon), while historical events are perceived as corroborating the notion that isolation is part of the Jewish predicament. In recent times, the sense of loneness and abandonment was greatly increased by the general indifference of the world, and the apathy of Western powers in particular, in the face of the Nazi effort to annihilate the Jews. Such a sense was also buttressed by a string of other modern-day events, among which the most salient are the following:

The strategic foundations of the Israeli perception of exceptionalism draw from both the cultural and historical sources of exceptionalism. For example, they draw on both cultural notions of isolation, cultural-historical experiences such as (the myth) of the Masada siege in the first century AD (which epitomizes the heroic struggle of the few against the many), or the historical experience of the Holocaust. Essentially, the strategic foundations of exceptionalism contain three elements: the perception of the basic imbalance of power between the Arab World and Israel, the perception of Arab declared hostile intentions, and the perception of Arab aggressive behavior.

The basic imbalance of power element refers to Israel’s inherent quantitative inferiority in the face of the demographic, budgetary, and military resources that the whole Arab World possesses, and to Israel’s geostrategic vulnerability—that is, lack of a measure of strategic depth. The intention element refers to voices in the Arab world that define the destruction of the Jewish State as the Arab strategic objective and occasionally discuss the extermination of the Jewish citizens of Israel. The behavior elements refers to the de jure state of war, occasional wars, continuous terror, and repeated efforts to deny Israel international recognition and legitimacy. 12

The Image of National Security Exceptionalismand Its Consequences

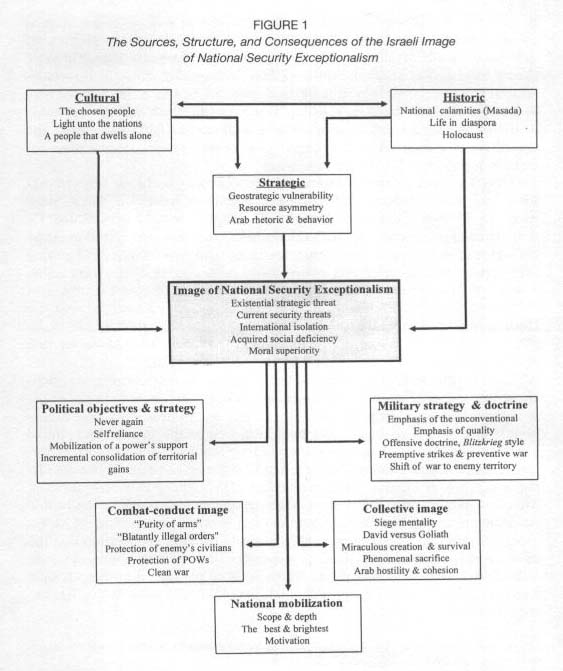

The Israeli image of exceptionalism, and in particular the interactions between elements of its strategic, historical, and cultural foundations, are at the heart of the Israeli definition of the country’s national security problem. These have helped to shape Israel’s threat perceptions, her operational definition of the national interest, and her political and military strategies. 13 They also contributed to the shaping of a number of other attitudes, self-images, and beliefs.

Most significantly, the foundations of the Israeli image of exceptionalism created a persistent sense that Israel is entangled in a conflict of unparalleled dimensions: total ideological antagonism, an almost untenable strategic relationship, and unmitigated hostile conduct. In fact, notions of national security exceptionalism percolated so deeply into Israeli society that they became integrated even into the discourse of society’s most critical minds. Indeed, exceptionalist argumentation can be found in the writings of distinguished scholars and independent opinion makers that were deeply critical of Israel’s foreign policy and rhetoric. Thus, for example, one scholar discusses “Israel’s very special security predicament . . .,” even though he argues that “Israel may not be as unique . . . as it sometimes presents itself.” 14 While another scholar finds that “Israel’s distinction in comparison to almost any of the states existing today . . .[is that it] faces a long term existential risk. . . .” 15 Similarly, in the wake of the March 1997 suicide-bomb attack in Tel-Aviv, a noted columnist of the liberal daily Ha’aretz depicted the terrorist act as one “the like of which is not to be found in the [whole] world.” 16

When Ben-Gurion and other Israelis raised the claims that “[Israel’s national] security problem [was] rather different from that of every [other] nation,” that it was “utterly unique and [without] parallel among the nations,” or “one of a kind problem, much as [Jews] are a one of a kind people,” 17 they all had one issue in mind—the existential nature of the threat Israel faces. 18 In the Israeli mind, the national security exceptionalism boiled down to one issue: “little” Israel alone faced the risk of irreversible collapse, a “destruction of the Third Temple,” 19 and the threat of genocide. Such fears were expressed in the wake of the Holocaust, but they continue to reverberate in Israeli society today. 20 In 1988, for example, forty years after the establishment of Israel, Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir explained in reference to the idea that “the Arabs want to throw the Jews to the sea” that: “If we carefully examine our reality, it has not changed. The Arabs are the same Arabs, the sea is the same sea. The objective is the same objective—the extermination of the Israeli state. . . .” 21

This acute perception of threat not only defines the Israeli-Arab conflict in total and irremediable terms, but also perceives the Arab world, as implied in Shamir’s words, as a monolith. Moreover, such perceptions lead to a formulation of the national security objective in negative and extreme terms, such as those embodied in the slogans, “never again” (which refers to the Holocaust) or “Masada shall not fall a second time.” In short, the conflict is defined in game theory language as an unalterable, iterated, zero-sum game, which includes Arab terror and insurgency in Israel and abroad. 22 In this game, Israel has to be prepared to fight and win recurring rounds of war, since any loss inevitably would mean the termination of the whole sequence, or more specifically, the end of Israel. Finally, in such a scheme of thoughts there is also no place for compromise, as it will only weaken Israel.

Naturally, such a representation of Israel’s security problems helps to preserve exaggerated perceptions of strategic threat and inferiority and a “siege mentality.” 23 During the Lebanon war, for example, Lieut. General Rafael Eitan, the chief of general staff (CGS) chastised journalists who dared question the image of Israel as a “David” struggling against an Arab “Goliath.” Ignoring the overwhelming Israeli military superiority, he argued that “the truth is that it is the other way round. . . . they [the Arabs] are Goliath: Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Iraq, Syria, the Palestinians, Libya, Algeria and all these states.” 24 Chaim Hertzog, a retired general and later president of Israel, did not hesitate to depict the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and Yasir Arafat as “the most cruel enemy the Jewish people have faced since Hitler.” 25

In any event, as Figure 1 suggests, the image of national security exceptionalism has several additional consequences. First, Israelis have been led to believe that the establishment of Israel, its survival, and its prosperity were exceptional. After all, if all three have been achieved in the face of exceptional problems and threats, then they must be exceptional too. Indeed, former Defense Minister Moshe Arens, explained in 1995 that: “The establishment of Israel was a modern miracle; an exceptional event in human history. Her survival, while constantly struggling against Arab aggression and terror in the hostile environment of the Middle East, seemed to me no less miraculous.” 26 Moreover, if that is the case, then one can also easily reach the conclusion that the capacity of Israeli society to meet its security challenges is no less exceptional. Indeed, Arens concluded that “surely, there is no parallel in history for such casualties, courage and energy of a small people that faces such overwhelming threats.” 27

The second important consequence of the image of national security exceptionalism is the conviction that Israel must devise strategic solutions that will match the level of the challenges Israel faces. Indeed, Ben Gurion had already concluded that: “We [Israelis] will not solve [our security problems] by means of simple answers, drawn from our past or adopted from other people. Whatever [solution] was adequate in the past, and for others—will not be adequate for us, since our security problem is one of a kind. . . . We will not withstand the [trying hour] unless we perceive our situation and needs in their geographic and historical singularity, and construct a security method adequate for that uniqueness.” 28

Similarly, four decades later, Ariel Sharon concluded that “Israel faces unconventional problems, and in order to continue to survive [it] must be able to devise unconventional solutions. . . .” 29 In fact, the idea that the Israeli strategic solutions, are, might, or perhaps should be exceptional was endorsed even in academia. Shai Feldman, for example, boldly suggested that Israel should establish an open nuclear deterrence against the conventional Arab threat, a choice that would be exceptional, as no other state by then dared to openly challenge the global nuclear regime of the Nonproliferation Treaty. 30

Finally, the image of national security exceptionalism gave the Israeli leadership a powerful utilitarian tool for the purpose of extracting resources and mobilizing support from society for whatever collective tasks it wanted to achieve. In the wake of the Six Day War, Yitzhak Tabenkin, a prominent figure in the activist faction within the Labor camp, referred to the instrumental value embedded in the threat component of what we term the image of national security exceptionalism as he argued that: “This feeling of solitude which resulted from the threat of extermination was one of the ‘secrets’ of our victory, and we must imprint it in our memories as a consideration in our decisions in the future.” 31

Indeed, the Israeli state cashed in on the image of national security exceptionalism when it mobilized and motivated Israeli society in general, and attracted and extracted the most from her best and brightest. Israel recruited for the backbone and spearhead of the IDF—the junior officer corps, and the top-line combat units and special operations forces—personnel from classes that in other societies often regard military service as an onus.

Israel’s National Security in a Comparative Perspective

In order to test the hypothesis that the Israeli national security problem is exceptional, I first specify an operational definition for national security. Using a deductive and relatively precise definition of the objectives of national security, which is also quite compatible with the thinking and behavior of Israel, helps to overcome the inherent ambiguity plaguing the concept of national security. 32 My definition separates two broad categories of national security: primary objectives that refer to existential and collective security issues, and secondary objectives that refer to individual security and private and public property. 33 The primary objectives of national security are the following: ensuring the survival of the state; guarding the state’s territorial integrity; maintaining the state’s political autonomy.

I discuss here solely primary objectives, as only they concern the existential question at the national level. These objectives comprise the hard core of national security. Furthermore, they are ordered hierarchically. The attainment of the first goal, survival, is more important than achieving either the second or third goals. Though, it is not clear at all whether achieving the second goal of territorial integrity is more important than achieving the third goal of political autonomy, or vice versa. 34

In any event, we can now compare the magnitude of Israel’s security problem to that of other states in terms of the nature of the threat, its severity, and its intensity. We can check whether other states in the international system and the Middle East have encountered similar or more acute threats to their survival, territorial integrity, and political autonomy. Then we can check whether such threats involved similar or worse strategic relations. Finally, we can decide whether other conflicts were as comprehensive, enduring, or demanding in terms of investment and loss.

The most general comparative review of Israel’s national security, as it appears in quantitative studies of enduring international rivalries (EIR), suggests that Israel experienced a high but not exceptional number of dyadic rivalry years (RY), militarized interstate dispute (MID) years, and war years (WY). 35 Yet the analysis of the EIR data suggests that Israel stands out as far as hostility, defined as MID to RY, is concerned. With two of its neighbors, Syria and Egypt, Israel’s MID/RY ratio is the highest among all the conflict dyads (90 percent and 94 percent respectively). The two next highest ratios of MID/RY, are those of India-Pakistan (82 percent) and of South Korea-North Korea (74 percent).

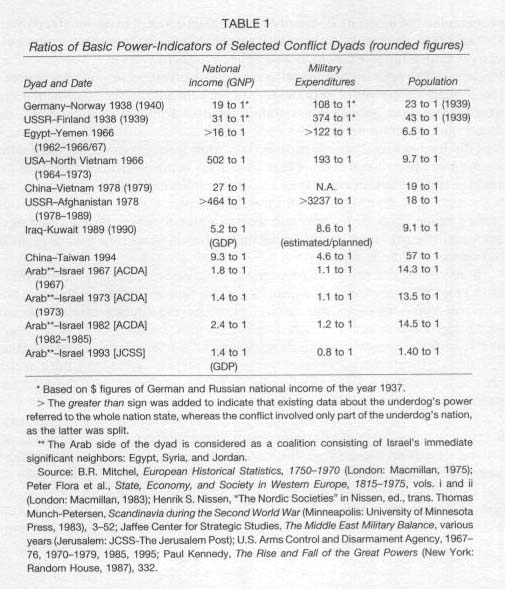

Still, the EIR data cannot indicate a real measure of Israeli national security exceptionalism, for it does not include dimensions of conflict—such as the power ratios, level of threat, or the cost and consequences of rivalry and war—which are necessary for a reliable comparative assessment of Israel’s security situation. Indeed, as Table 1 indicates, a most elementary review of dyadic power relations of actors engaged in tense and/or violent conflict clearly indicates that the security predicament of other states was or is more severe than that which Israel faces.

In order to answer the question of exceptionalism, let us consider strategic relationships in a qualitative manner, starting with a deductive argument about which strategic relationships potentially involve an equal or even worse national security threat than that which Israel has experienced. Then, let us briefly recall a few empirical cases that seem to corroborate my deductive argument.

At least three types of conflict situations—all involving actors that fall within the definition of small state 36 —involve inherently worse strategic situations and consequently potentially greater threats, risks, and costs than the Israel experience: cases involving seceding nations (usually not quite full states); cases involving states sandwiched between two powerful rivals; cases of small states living on the frontier of empires or ambitious regional powers.

States in the first and third categories (seceding and frontier) are in a worse situation, since they face mighty political units that are far more cohesive and powerful than the Arab community. States in the second category (sandwiched) are in a worse situation, because they face a dual threat over which they have no control whatsoever, since it arises from their geopolitical position.

Biafra, Bosnia, and Chechnya, are good examples of seceding nations that became involved in manifestly more threatening and demanding struggles than Israel. Examples of sandwiched states that experienced a worse strategic predicament than Israel are Poland during much of its interrupted national life, Belgium and the Netherlands during the first half of the twentieth century, and Central European states during the cold war. Examples of frontier states whose powerful and ambitious neighbors threatened, robbed, or violated their autonomy, territory, or sovereignty are Albania from birth and until the end of World War II; the Baltic states, Czechoslovakia, and Finland since shortly before World War II and up to the end of the cold war; Latin and particularly Central American and Caribbean states since the mid-nineteenth century, and Chad in the 1970s and early 1980s. 37

Some of these and other international actors—Poland, Albania, Serbia, Montenegro, the Baltic states, Biafra, and Tibet—simply ceased to exist, temporarily or permanently, as a result of other states’ aggression. For similar reasons, other potential states have never quite made it to independence. East Timor, for example, escaped Portuguese rule only to discover shortly thereafter that Indonesia “accepted” a merger with it on 17 August 1976, declaring its territory as Indonesia’s twenty-seventh province. 38 Some of the above states and provinces also experienced alien colonization designed to thwart their future secession. Even today, a few states, most notably Taiwan, have good reasons to fear dismantling.

Moreover, dire existential threats await not only small actors. In June 1950, South Korea was the victim of an offensive by its rough northern equal that would have put an end to its existence had the United States decided not to intervene. Of course, shortly thereafter, North Korea faced a similar threat that would have ended in its destruction had it not been for China’s decision to intervene. South Vietnam perished after two decades of independence, and Kampuchea was conquered by Vietnam. The superpowers have faced since shortly after the dawn of the nuclear age thermonuclear armageddon. Indeed, the citizens of Europe, the United States, and the USSR, have lived under the threat of nuclear annihilation, a threat Israelis have yet to face.

Now, though many of the states mentioned managed to retain their sovereignty, they nevertheless suffered from a significant reduction in their political autonomy and control over their territory and other affairs. For example, most East European members of the Soviet bloc (except Yugoslavia, Romania, and Albania) hardly enjoyed any measure of sovereignty as far as their foreign relations and internal political order were concerned. They had to follow the dictates of the USSR, and when they failed to obey Moscow, their sovereignty was violated and their leadership was swiftly removed (Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Afghanistan). Even less tightly controlled small neighbors of the USSR could not afford to practice full autonomy. Post-1945 Finland remained out of the Soviet institutional grip but was still deprived of much of its autonomy in foreign policy and even domestic matters (all that, after Finland had already lost vast territories in the 1939 Winter War). One must also remember that life on the frontier or under the proclaimed sphere of influence of democratic powers was not necessarily safer, at least as far as political autonomy was concerned. Communist Cuba lived under continuous American threats and economic pressure, occasionally suffering from American aggression. Other Latin American states—including Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Chile, Nicaragua, Panama, and Grenada—were also victims of American covert or overt aggression.

Finally, even within the Middle East, the national security situation of Israel seems to be relatively bearable. Some Arab states are locked in a significantly more problematic situation than Israel. They are either sandwiched between or on the frontier of states that are far stronger than them and that have occasionally become ambitious, threatening, and aggressive. Jordan is neighboring three such states—Iraq, Syria, and Israel. These neighbors have all at one time or another threatened the Jordanian regime, territorial integrity, and even existence; and they still might make Jordan the site of military collision between any two of them. Another Arab state, Lebanon, has already been a victim of such predicament. In 1982, it became the site of an Israeli-Syrian collision, and today it is virtually run by the Syrians and is de facto divided between Syria, local militias, and Israel. Bahrain is another small Middle Eastern state that should be concerned over its existence. It was claimed by both pre- and post-revolutionary Iran, whose spokesmen occasionally depicted it as their country’s fourteenth province. 39 Finally, Kuwait, as of its independence on 25 June 1961, has been claimed by Iraq, which tried and almost succeeded in annexing it in 1990. 40

In short, Israel’s security situation is better than that of other regional actors. Moreover, its depiction as a small state became inappropriate, as it is not locked anymore in acutely inferior strategic relationships with its immediate neighbors—a condition which is the very hallmark of a small state. A power-related time analysis of the dynamics of the Arab-Israeli conflict shows that Israel’s relative position vis-á-vis its Arab enemies has improved considerably and consistently over the years.

Now this dynamic of the balance of power in favor of Israel is not recent nor even a post-1967 phenomenon. Studies by Yair Evron and others reveal that the relative improvement in Israel’s position vis-á-vis its immediate Arab foes started as early as the 1950s. 41 For example, Israel’s rate of defense out-lays growth in the period 1950-1970 exceeded on average that of its Arab neighbors. 42

After 1967, the relative improvement in Israel’s security only accelerated, though initially the rate of defense outlays may not have indicated that. First, Israel’s geostrategic position improved as a result of conquest. Second, its military capabilities, and in particular superiority in terms of kinetic military power, increased as a result of the transition from French to American military technology and aid. Third, as Dan Segre and Daniel Ben-Yaakov further note, Israel’s position improved in terms of the quality of its human capital (as measured by scientific production) and economic growth that followed the “science and technology based industrial revolution” it experienced. 43 Finally, as Zeev Maoz recently demonstrated, the economic gap between Israel and its ”strategic reference group” grew further in Israel’s favor in the 1980s and 1990s, and its defense outlays grew while those of its rivals declined in the later part of the study period (1986-1994). 44

Still, in order to fully appreciate the importance of the change in Israel’s national security, our discussion needs to go beyond material dimensions and to seek to understand the actual conventional threat Israel faces as well as its political dimensions. A good starting point would be the premise that the conventional strategic threat Israel faces is a function of three related factors: geostrategy, power relations, and the probability and potential damage of a strategic surprise attack. For example, of all possible threats (excluding a massive nonconventional attack), a strategic surprise by a grand coalition (Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and Iraq) on two fronts is the worst in terms of magnitude and severity. In such a scenario, the Egyptians tie down a considerable part of Israeli forces in the southern front, while the eastern members of the coalition strike on a broad front, right into the heart of Israel, before Israel fully mobilizes or adequately deploys its forces. The second worst threat comes from a strategic surprise by the above coalition minus its Egyptian component—by a broad eastern coalition (Syria, Jordan, and Iraq). The third worst threat could be that posed by a strategic surprise by a limited two-fronts coalition (Egypt and Syria), etc. 45

What these scenarios make clear, by implication, is that the threat level that Israel faces is not simply a function of the balance-of-power and Israel’s geostrategic vulnerabilities. Rather, the threat level is also a function of regional and international politics. 46 These decide the structure of hostile coalitions, and consequently the magnitude of the threat of strategic surprise, and the potential damage carried in its wake. In short, a reliable account of the dynamics of Israel’s national security situation cannot ignore diplomatic and strategic developments in the world in general, among Arab states, and between the Arabs and Israel in particular (including possible Arab interests in Israel’s survival). 47

Adjusting the assessment of the Arab threats to Israel to regional and global politics soon reveals that Israel’s security position has improved beyond what material analysis suggests. Israel’s enemies’ patron, the Soviet Union, ceased to exist; and its two neighbors who share its longest borders, Egypt and Jordan, decided to sign peace agreements that contain important strategic arrangements that Israel sought. In short, the number of states that threaten Israel with any kind of territorial surprise attack has shrunk over time to one—Syria. Of course, Israel’s immediate neighbors can still change heart and threaten Israel. But the current and near-future threat level still remains lower than that created before the peace agreements. The change back to hostility will involve serious cost and will give Israel time to prepare for its consequences.

The improvement in Israel’s national security situation was noted by several scholars, including Jerome Slater and Zeev Maoz. 48 Maoz, for example, demonstrates that in comparison to the period 1945-1970, the Arab-Israeli conflict of the last three decades occupies a declining share of the region’s security problems, as measured by the problems’ severity. 49 Moreover, the improvement in Israeli security was indicated clearly by regional and global development. First, Israel was spared much of the pain and horror certain Arab powers inflicted on Middle Eastern nations. For example, Israelis avoided the fate of the Yemeni and the Kurds, who were subjected to gas attacks by the Egyptians and the Iraqis respectively. Similarly, Israel avoided the kind of civil and military bloodshed that Iran and Iraq inflicted on each other, and the kind of destruction Kuwait suffered at the hands of Iraq. Second, the improvement in Israel’s national security situation was reflected in the transformation of the strategic calculus of Arab states, and their readiness to establish open commercial ties, conduct peace negotiations, and conclude diplomatic relations with Israel. 50 Third, the consistent improvement in Israel’s national security was indicated by the consolidation of its international status after long years in which Israel was subject to an effective Arab delegitimation campaign.

Israel’s National Security and Moral Exceptionalism

Thus far we have not discussed a major consequence of the Israeli image of exceptionalism, which springs from the notion that the Jews were ordained to be a light unto the nations—the conviction that Israel can be a moral beacon while using its military might, and can somehow untangle the Gordian knot created by the conflict between the necessities of security and the ethics of human conduct. The Israelis believe that their presumed moral exceptionalism is a vital component of national power and of their strategy to deal with the country’s “exceptional” security situation. IDF officers and soldiers are instructed to abide by ethical rules of conduct in war, which are embodied in the Israeli concept of the “purity of firearms” (tohar ha’neshek) and the permission/instruction to refuse to obey “blatantly illegal orders” (pkudot bilti hukiot be’alil).

This central moral tenet of the Israeli image of national security exceptionalism must be approached, much as were other tenets of that image, as a proposition to be evaluated rather than a given assumption. The evaluation itself can be accomplished on the basis of a review of the Israeli conduct in two realms: international military trade (and aid), and military conduct in war and occupation.

The review of Israeli’s military trade policy suggests that Israel does not break with the prevailing patterns of the international arms and military market, which are characterized by the preponderance of utilitarian calculations over ethical considerations. In short, Israel’s military-trade and aid policy is formulated on the basis of ordinary economic, strategic, and diplomatic calculations. It has done military business with some of the most corrupt, cruel, and unjust regimes in the world including the pariah regimes of apartheid South Africa, Mobutu’s Zaire, Communist China, and Argentina’s junta (a country whose government and army were also plagued by anti-Semitism). 51

The review of Israel’s military conduct, the realm with which Israelis and a few scholars associate the country’s presumed moral exceptionalism, does not support the moral claim. 52 Let us first inform ourselves of the basic concepts of moral philosophy and international law regarding conduct in war. 53 Our departure point is that “war [remains] . . . a rule-governed activity, a world of permissions and prohibitions,” 54 a tenet that is at the root of the Western body of principles, which presumably guide warring sides that consider themselves civilized. Some of these principles have already been incorporated as binding obligations in international conventions that deal with restraints on the conduct of war.

Among these principles, two types concern restraints on combat behavior: absolutist and utilitarian. 55 Absolutist principles deal with what one is doing. They forbid “doing certain things to people, rather than bringing about certain results.” 56 Murder and torture, for example, are “the most serious of [such] prohibited acts.” 57 Utilitarian principles are concerned with consequences. They revolve round the idea that in the pursuit of legitimate military goals, one should try to minimize evil. In short, the distinction between absolutist and utilitarian principles is between what one is allowed to do to people and what merely happens to them as a result of what one does.

Absolutist restrictions are organized in two clusters of prohibitions: those concerning whom soldiers can kill; and those concerning when and how soldiers can kill. 58 Thus, certain people may not be subject to hostile treatment, while others, though legitimate targets, can be considered as such only under certain circumstances. 59 For example, noncombatants are granted immunity at all times from an attack directed at them. 60

Among utilitarian principles, the double effect principle, which concerns the fate of civilians placed in harm’s way, is central. 61 In essence, this principle defines a military act as illegitimate if its consequences include deliberate damages to civilians. According to the double effect principle, a military act might be legitimate according to utilitarian principles even if it involves the foreseen but unintended death of noncombatants. The act must still meet the somewhat vague requirements of proportionality—that is, the military benefit should surpass the evil of the unintended damage the act brings upon noncombatants.

A slightly different way to assess the morality of state acts is to measure the morality of the behavior of states according to the relations between the principle of necessity, and the principles of humanity and chivalry. 62 Necessity is defined in terms of the value of the desired military goal. However, the goal must be of immediate indispensability, limited by the principle of proportionality, directed toward legitimate military ends and achieved by legitimate military measures (that is, measures that are not prohibited by the law of war or natural law). Humanity requires that the actions should not cause unnecessary or disproportionate damage or suffering and should not violate the principles of discrimination (noncombatant immunity). Chivalry demands that the behavior be honorable, even toward the enemy.

My evaluation of the moral standing of a state can be based on the concepts discussed, but it cannot be comprehensive unless we also consider the degree of responsibility of the state for moral transgression. This responsibility is easy to define and a function of the position of the perpetrators in the state’s hierarchy. Explained inductively, I submit that a state’s culpability in the case of the murder of enemy civilians by lower ranks, on their own initiative, is smaller than when the very same act is initiated by higher authorities.

With these premises in mind we can now divide the realm of military conduct into four important issue-areas—enemy-civilians during war, POWs, occupation, and counter-insurgency and antiterrorism campaigns—and discuss ethics in terms of the severity of moral transgressions and the responsibility of the state. The severity will be measured according to the type of prohibition transgressed and the scope of transgression. The responsibility will be measured in relation to the position of the perpetrator in the state hierarchy.

The evaluation of Israel’s behavior according to these standards reveals that not all acts depicted as Israeli violations of military and combat ethics are of the same class. A few Israeli actions that ended in horrible consequences should not be considered as indicative of immorality, as they were inadvertent. For example, the bombing of an Egyptian school during the war of attrition or the 1996 Kafr Canna artillery massacre in Southern Lebanon should not a priori be considered as refuting the claim of moral exceptionalism, though the acts do bear moral responsibility. Other episodes, such as the Dir-Yasin massacre and the Sabra and Shattila massacre, which could have been easily averted or stopped early, resulted in clear transgression of moral standards and thus cast doubts on the claim of moral exceptionalism. Still, they do not clearly disprove the claim, as the immoral outcomes seem not to have been the result of premeditation or intention. A significant number of other episodes, however, seem to contradict the claim of moral exceptionalism. These episodes involved war crimes that were perpetrated by lower- and middle-level Israeli ranks who interpreted ambiguous orders in a criminal manner, or took advantage of a permissive atmosphere. In short, they involved severe transgressions of absolute or utilitarian principles of war ethics, and the responsibility involved intentional default or even design at various levels of authority. Such transgressions include the dispersed yet massive eviction—at times forced or encouraged, and all too often accepted with indifference—of Palestinian Arabs during the 1948 War of Independence (and to a lesser degree, after the 1967 Six Day War). 63

They also include a string of other cases—the 1953 Qibya reprisal; the 1955 private vengeful raid of Meir Har-Zion and friends, which ended in the arbitrary murder of five Bedouin shepherds; the 1956 Kafr Kassem summary execution of forty-seven Israeli Arabs who returned from work after curfew; the murder of Egyptian POWs during the 1956 Sinai Campaign; and several documented and undocumented instances of murder of PLO captives and other people during the 1978 Litani operation. 64 Finally, there is a class of cases that defeats the claim of moral exceptionalism most prominently, as they involved actions that were ordered by the highest authorities and that ended in the abuse of the utilitarian principle of proportionality and/or the absolute principle of discrimination. The following cases fall within this class: the June 1972 shooting down of a Libyan civilian airliner over the occupied Sinai peninsula, the artillery assault on the cities of the Suez Canal during the War of Attrition, the bombardment of Beirut during the Lebanon war, and the relentless bombardment of villages in Southern Lebanon during the 1993 Din-Ve’heshbon Operation. 65

Additional refutation of the Israeli claim of moral exceptionalism can be found in the general attitude of the Israeli society toward the Arabs and in the chronicles of Israeli behavior during the occupation of Gaza and the West Bank. 66 Most Israelis either ignored or were indifferent to the prolific documentation of collective and individual abuse of Arab human rights in the occupied territories, while many of them are even supportive of abuses of power such as beating, excessive use of deadly force, collective punishment, demolition of private residences, administrative detention without indictments or trial, torture, and deportation. If anything, only a minority within Israel seems to have realized that Israel could not overcome the inherently exploitative, unjust, and corrupting nature of occupation. Israeli society at large, it seems, mostly views the Palestinians as ungrateful for the “enlightened” Israeli occupation that presumably bestowed on them development and prosperity.

Yet the most reliable means of assessing the claim of moral exceptionalism is to check the Israeli conduct in the issue-areas of counter-insurgency and antiterrorism (issues that are also often part of the reality of occupation). These issue areas provide a particularly good opportunity to evaluate moral exceptionalism, because they both involve a high dose of frustration and are less clearly regulated than other forms of conventional warfare. 67 If Israeli moral exceptionalism exists, it should be clearly evident in Israel’s capacity to act morally in spite of the strong temptation to abuse its powers and emphasize above all else efficacy and effectiveness, and in spite of the fact that the fields of counter-insurgency and antiterrorism are relatively poorly regulated.

During the long years of the Arab-Israeli conflict, the Arabs and the Palestinians perpetrated horrible terrorist attacks against Israelis. Many of these attacks can be defined only as war crimes or other crimes. However, Israel did not adhere to what her presumed moral superiority should have dictated. Indeed, Israel has all too often adopted methods that were banned by international law, such as when its forces twice intercepted Arab civilian jets, in order to capture the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) leader George Habash. Moreover, while such failed efforts involved no morally repulsive consequences, other Israeli acts and methods of antiterrorism and counter-insurgency—including the use of torture and hit-teams—involved breaches of international ethics that did result in travesties. For example, following the Munich massacre of eleven members of the Israeli 1972 Olympic Team, Israel launched an assassination campaign against those who it suspected were responsible for the crime. In July 1973, this campaign ended in the assassination of a man who was mistakenly identified as a key Black September operative. The innocent man, an Arab waiter named Ahmed Bouchiki, was gunned down in front of his bewildered pregnant wife.

Of all “exceptions” to the presumed Israeli moral exceptionalism in the issue area of counter-terrorism, the most telling is perhaps the Bus 300 affair. This affair started on 12 April 1984, when four juvenile (17-18 years old) Palestinian terrorists highjacked an Israeli commuter bus. The bus was raided by an Israeli assault team and two of the terrorists were captured in good health. After a short brutal interrogation on the scene, the terrorists were taken by GSS officers to an interrogation center. However, while on the road, the head of the GSS Department of Operation, Ehud Yatom, received instructions from his chief, Avraham Shalom, to kill the two captives. Yatom followed the order, 68 and the official version was that all four terrorists were killed during the army assault. Shortly thereafter, the press provided proof that two of the terrorists were captured alive. The government was embarrassed by the moral side of the disclosure and by the fact that it was caught lying, and decided to limit the damage by establishing an investigation committee. For a while, senior army officer, Brigadier General Yitzhak Mordechay, later the defense minister (1996-1999), who participated in the initial brutal investigation, was suspected of the killing. However, at the end, the committee failed to reach any conclusions.

Some two years after the event, it became clear that the committee fell prey to a GSS conspiracy. Three senior GSS officers, all familiar with the details of the killing (one of them allegedly instrumental in the cover-up), disclosed the truth to the government and to the attorney general. It then became clear that the leadership and ranks of the GSS had committed perjury, conspiring to mislead the civil authorities. Eventually, GSS Chief Shalom resigned. Yet in a bizarre twist of the law and ethics, President Chaim Herzog pardoned the GSS officers who were involved in the crime, although none was found guilty or even put on trial.

In the tumult, the key moral issues were almost lost completely. The major issue became the perjury of the GSS command and ranks. The role of the officers who participated in the initial brutal beating (presumably on the basis of the ticking bomb principle) was hardly debated. The fact that presumably morally exceptional people could murder wounded captives or obey a blatantly illegal order (by Israeli conventions) and ignore an absolute prohibition (by international conventions) bothered only a few. Even of greater significance, it became clear that at least in some circumstances this sort of criminal conduct was not all that unusual, and still very few people seemed concerned. Finally, Yatom, the confessed killer, continued a successful career in the GSS for another eleven years after the murder, and no GSS officer ever protested publicly against the conduct of his fellow officers.

In short, the Bus 300 Affair, as well as other incidents, indicate that Israel does not display moral exceptionalism. Israelis have violated absolute and utilitarian ethical rules of military conduct more often and extensively than they and others have claimed. Moreover, these violations also suggest that state agents and the public at large rarely value Arab life. Israel’s morality, as opposed to the country’s moral image, concerns at best only a limited professional and intellectual elite in the Justice Department, academia, and the media.

Still, critical discussion of Israel’s proclaimed moral exceptionalism does not lead to the conclusion that Israel stands at the opposite moral pole. Israel does not display exceptional morality, but neither does it display exceptional immorality. There is nothing unprecedented or exceptional in Israeli conduct in the international arms and military market, during war and occupation, or while fighting insurgency and terrorism.

The Israeli utilitarian export of arms and know-how is no more outrageous than that of self-proclaimed moral beacons such as France, Germany, Britain, or the United States. If anything, Israel is probably in a slightly better moral position as its arm-sales are motivated by more than profit and employment consideration: to keep alive vital defense industries that serve it in an ongoing struggle. Nor has Israel violated absolute and utilitarian standards of jus in bello more often or more severely than other nations. Excessive collateral damage and attacks on civilians, forced evacuation and resettlements, killing of POWs, and other war crimes have all been integral parts of the history of war almost everywhere. Similarly, institutionalized murder, torture, deportation, and cover-up have been part and parcel of almost any counter-insurgency campaign.

Consider the following events: the Russian conduct in the war in Chechnya; the American PGM attack of a civil air-raid shelter in Baghdad during the 1991 Gulf war; the Spanish secret war against the Basque movement, ETA; the Soviet shooting down of a Korean Air Lines passenger-flight; the general British treatment of Irish Republican Army (IRA) suspects in Ireland and the 1988 summary execution of three unarmed IRA members in Gibraltar in particular; the massive American bombing campaigns in South and North Vietnam, their Phoenix anti-insurgency campaign, and the My Lai massacre; or the French conduct during the Algerian war in general and during the battle of Algiers in particular. 69

To sum up, Israel’s conduct towards its Arab enemies, be they soldiers, terrorists, or civilians, did not display an outstanding commitment to ethical or moral values. Israelis have gone down the slippery slope of brutalization in war, much as did members of other “civilized” societies before them. Still, Israel as well as other democracies are set apart from brutal regimes that perpetrate war crimes as part of their war strategy or as a means of occupation—as we have seen in ethnic conflicts such as in Bosnia or Rwanda. In short, its conduct, while not exceptionally moral, is still more ethical than that observed and expected from certain nondemocratic states, including those in the Middle East.

Conclusion

The most conspicuous conclusion one can draw from this article is that Israel is not exceptionally vulnerable nor involved in exceptionally difficult strategic relations with its neighbors. The security situation of other small states, which are or were trapped in asymmetric relationships with their neighbors, is or was worse than that of Israel. That in itself should not be all that surprising. As international relations theorists have noted, life at the mercy of international environment leaves little room for exceptionalism. States and societies face similar problems and go through a process of socialization that makes them and their conduct converge. 70 While Israel and its problems surely contain idiosyncrasies, Israel’s strategic choices and conduct are not unprecedented or exceptional. Considering Israel’s relative economic growth, the fragmentation of the Arab world, the end of bipolarity, and Israel’s improved strategic situation, it seems hardly justified to continue analyzing Israel as a small state.

All that, however, does not suggest that Israel’s national security problems are trivial or insignificant. The trajectory of middle-eastern and world developments is not necessarily monotonically positive, and thus Israel’s gains could be constrained within a temporal window of opportunity. This window may currently be starting to close, and Israel’s strategic gains may be eroding, as effective weapons of mass destruction and reliable long-range delivery systems are introduced into the Middle East. 71

If Israel’s national security problems are not all that exceptional, the derivatives of the image of exceptionalism are as worthy of endorsement as the image itself. Israel was not called upon for an unprecedented level of mobilization, nor did it pay an exceptionally high price for the purpose of achieving its objectives. Rather, an honest analysis suggests that other nations faced far greater difficulties, have sacrificed much more, and have often gained far less in the course of their struggles and sacrifices. For example, one may want to consider the levels of heroism, sacrifice, and pain in the Finnish Winter War against the USSR, the Algerians’ war for independence against France, the communist struggle in Vietnam against the United States, the Kurds’ struggle against three regional powers—Iran, Turkey, and Iraq—and the recent struggles of the Bosnians and Kosovars.

There remains the utilitarian question: Is it beneficial or harmful for Israel to believe in exceptionalism? On the positive side, a self-sense of national security exceptionalism can at times serve a nation well. Combined with a sense of urgency and necessity, it can increase a community’s capacity to achieve collective goals. In ordinary times the Israeli image of national security exceptionalism served as a means of decreasing social tensions and centrifugal tendencies within Israel. In times of peril, it provided Israelis with extra necessary strength. Society preserved its cohesion, was more ready to mobilize, its threshold of tolerance to sacrifices was raised, and it was goaded to achievements as the balance between the public and private interest was shifted in the collective’s direction.

However, since the Israeli image of national security exceptionalism distorts reality, it is also potentially harmful. Being a source for delusions, it may undercut rational analysis, for the capacity to form an accurate assessment of a means-ends relationship may be lost. It has already been argued that one dimension of the Israeli image of national security exceptionalism—the inflated perception of threat—contributed to the preponderance of military over political considerations.[ 72 It has also been argued that this and other derivatives of that image were partially responsible for inadequate responses in times of conflict and crisis and for unnecessarily costly operational decisions.

For example, in the early 1970s the inherent belief in Israeli-Jewish exceptionalism led to a general contempt towards the Arabs and their capacity to fight, and to an overconfidence in the Israeli power to deter its neighbors. In October 1973, as the Yom-Kippur War erupted, the exaggerated perception of Israel’s vulnerability and of Arab objectives led to panic and overreaction. 73

More significantly, a false sense of exceptionalism can create among leaders and their followers a psychological climate that leads to the disregard of international constraints and the experience of other communities. How can a nation or its leaders, who perceive themselves and/or the situation as exceptional, draw lessons or establish a rational process of learning from the experience of others? In short, a belief in exceptionalism can lead to a primitive interpretation of international reality and to the following arguments: no existing solution can be adopted since the problems are unprecedented; only an exceptional solution is adequate; such a solution is feasible and can overcome the circumstances or historical quasi-laws, since it is devised and executed by exceptional people.

When the most important dimensions of national security and state strategy are involved, notions of exceptionalism can lead to risky and badly calculated adventures. Thus, the renouncing of notions of exceptionalism, though difficult and costly, might at some point become essential. It could help to avoid setting over-ambitious goals and to develop irrational perceptions of ends-means relationships. It could prevent an ethical regression that can stem from the idea that “morally superior” people are entitled to follow their own standards of behavior.

In this respect, several segments in Israeli society and among the elites have already started to distance themselves from the image of national security exceptionalism. This process of sobering up and the consequent changes in the Israeli strategy, doctrine, and self-perception have already become noticeable. 74 As a result, Israel has entered a delicate process of negotiations on conflict resolution with its neighbors, a process which has replaced the strict reliance on power politics. Still, Israeli society at large is not yet ready to abandon the rhetoric of exceptionalism. Significant segments of society adhere, perhaps even more firmly than before, to various dimensions of exceptionalism. These segments include, the hard ideological core of the Herut movement, members of the Labor activist faction, a large proportion of the national-religious community, and recently a growing portion of the religious-orthodox masses. The religious sectors may find it particularly hard to give up their image of exceptionalism, as it is part of their belief system and communal identity. These sectors are convinced that they are the spearhead of Jewish and Israeli exceptionalism, and that they are living in an exceptional historical moment, the time of redemption (geula)—a time when the alleged secular laws of history can be circumvented and a Utopian dream can be achieved against all odds.

The vision generated by this brand of exceptionalism contradicts some key tenets of universal ethics and thus reduces the Israeli national capacity to mobilize the secular and liberal constituent of society. If led by such a vision, Israel may find itself aspiring to achieve extreme objectives with a severely reduced capacity to mobilize national resources. The goals will be exceptional and so perhaps would be the spirit of some Israelis. But, the ends-mean relations will become fundamentally irrational.

If in order to succeed, as Dror suggests, Israel has, to “progress on a narrow bridge between inferiority and superiority complex,” 75 unless the Israeli society and leaders abandon the belief in, and vision derived from, the notion of exceptionalism, they are likely to reap the worst of the two complexes rather than pass unharmed between them.

Endnotes:

*: The author wishes to thank Daniel Bar-Tal, Gad Barzilai, Avi Ben-Zvi, Azar Gar, Peter J. Katzenstein, Aharon Klieman, and Yossi Shain for reading, commenting, and suggesting how to improve this article. An early version of this essay was presented at the conference on Israel in a Comparative Perspective: The Dynamics of Change, University of California, Berkeley, 2-4 September 1996. Back.

Note 1: See John A. Armstrong, Nations before Nationalism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982), 5; and Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities (New York: Verso, 1991), 6-7. Back.

Note 2: On Britain, see Liah Greenfeld, Nationalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992), 78-86. On American exceptionalism, see Samuel P. Huntington, American Politics: The Promise of Disharmony (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1981); and Seymour M. Lipset’s sociological work, American Exceptionalism (New York: W. W. Norton, 1996). For a concise statement about American foreign policy exceptionalism, see Huntington, “American Ideals Versus American Institutions,” Political Science Quarterly 97 (Spring 1982): 1-37. For a critique of this idea, see Joseph Lepgold and Timothy McKeown, “Is American Foreign Policy Exceptional?” Political Science Quarterly 110 (Fall 1995): 369-84. Back.

Note 3: Jack Snyder, Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambition (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991). Back.

Note 4: Indeed, Jack Snyder doubts the relevance of “cognitive” explanations that attribute imperialist behavior to ideology or formative experiences. See ibid., 28. Back.

Note 5: See Shlomit Levy, Hanna Levinsohn, and Elihu Katz, Belief, Observance and Social Interaction among Israeli Jews (Jerusalem: The Louis Guttman Israel Institute of Applied Social Research, 1993), 12, 119. In this survey, 74 percent of Israelis thought it was “important” or “very important” to believe in God, and 79 percent described themselves as “strictly,” “mostly,” or “somewhat” observant. While 63 percent firmly believed in God, 24 percent doubted God’s existence, and only 13 percent declared that they did not believe in God. Fifty percent believed that the Jews were the chosen people, while only 20 percent did not accept this view. See ibid., 108. The majority of believers seems to include the political elite. According to a survey of the Ha’aretz daily, 75 percent of the Knesset Members (MPs) believed in God. See Ha’aretz, 25 July 1996, weekend supplement. Back.

Note 6: Ha’aretz, 25 July 1996, weekend supplement. Back.

Note 7: Quoted in David Ben-Gurion, Yihud Ve’ Yiud [henceforward Distinction and Destiny] (Tel-Aviv: Ma’arachot, 1980), 142. Back.

Note 8: Quoted from a speech to Senior IDF officers, 5 March 1959. See Ben-Gurion, Distinction and Destiny, 322. Back.

Note 9: From a speech of 10 November 1960. See Ben-Gurion, Distinction and Destiny, 354. (Emphasis added.) For similar contemporary views, see Benjamin Netanyahu, Makom Tahat Ha’Shemesh [the American edition titled A Place Among the Nations] (Tel-Aviv: Yediot Aharonot, 1995), 400, 401. Back.

Note 10: J. Doriel, Terruf Maarachot [Systems’ Madness] (Tel-Aviv: Mabat, 1981), 145-46; see also Netanyahu, Makom, 365-69, 397-98, esp. 367. Back.

Note 11: See, for example, Ben-Gurion, Distinction and Destiny, 362. Back.

Note 12: See, for example, the review in Aaron S. Klieman, Israel and the World after 40 Years (Washington: Pergamon-Brassey’s, 1990), esp. 5-17. Back.

Note 13: On the Israeli national security belief-system, see Asher Arian, Ilan Talmud, and Tamar Hermann, National Security and Public Opinion in Israel, JCSS study no. 9 (Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Post, 1988), 16-30; Michael I. Handel, Israel’s Political-Military Doctrine (Cambridge, MA: Center for International Affairs, 1973); Dan Horowitz, “The Israeli Concept of National Security” in Avner Yaniv, ed., National Security and Democracy in Israel (Boulder, CO: Lynn Rienner, 1993), 11-53; and Avner Yaniv, Politika Ve’estrategya [Politics and Strategy] (Tel-Aviv: Sifriat Poalim, 1994), 14-34. Back.

Note 14: Yaniv, National Security and Democracy, 230. Back.

Note 15: Yehezkel Dror, Estrategya Rabati Le’Israel [A Grand Strategy for Israel, henceforward Grand Strategy] (Jerusalem: Academon, 1989), 26. Back.

Note 16: Yoel Marcus, Ha’aretz, 23 March 1997. Back.

Note 17: The first two quotes are from a 5 September 1949 speech, and the third quote is from an 18 August 1952 speech. See Ben-Gurion, Distinction and Destiny, 72-73, 179. See also a speech to senior officers, 12 December 1957, in ibid., 30; and Shimon Peres’s opening statement in Kela David [David’s Sling] (Jerusalem: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1970), 1. Back.

Note 18: See Dan Horowitz, “The Israeli Concept of National Secrity,” 11. Back.

Note 19: This image was used by Moshe Dayan during the early stages of the 1973 war. See Chaim Herzog, The War of Atonement (Boston: Little Brown, 1975), 97, 116. Back.

Note 20: See Ben-Gurion’s speeches 26 August 1947, 2 January 1951, and 5 July 1955 (to IDF officers) in Distinction and Destiny, 16-17, 148, 205-206. Back.

Note 21: Quoted in Daniel Bar-Tal and Dan Jacobson, Security Beliefs among Israelis: A Psychological Analysis (Tel Aviv: The Tami Steinmetz Center, 1996), 21 from Ha’aretz, 25 January 1988. Refael Eitan, former Israeli chief of the general staff (1978-1983) and a minister in several governments since then, is of similar opinion. See Eitan (with Dov Goldstein), Sippur Shel Hayal [A Soldier’s Story] (Tel Aviv: Ma’ariv, 1985), 333; and an interview in Ha’aretz, 20 August 1996. See also Netanyahu, Makom, 185. Back.

Note 22: See Ben-Gurion’s reference in a 2 January 1956 speech and on 15 October 1956 in Distinction and Destiny, 231, 258. Back.

Note 23: On Israel’s society security creed, see Bar-Tel and Jacobson, Security Beliefs among Israelis; and Arian, Talmud, and Hermann, National Security and Public Opinion in Israel. On the scope, origins, and cultural prevalence of the siege mentality, see Daniel Bar-Tal and Dikla Antebi, “Siege Mentality in Israel,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 16 (Summer 1992): 251-75. Back.

Note 24: Yediot Aharonot, 17 September 1982. Back.

Note 25: Maariv, 9 July 1982. Back.

Note 26: Moshe Arens, Milhama Ve’shalom Ba’mizrach Ha’tichon, 1988-1992 [War and Peace in the Middle-East] (Tel-Aviv: Yediot Aharonot, 1995), 35-36. (Emphasis added.) Back.

Note 28: September 1949 to the Knesset. Ben-Gurion, Distinction and Destiny, 75. Back.

Note 29: Ariel Sharon with David Chanoff, Warrior (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1989), 531. Back.

Note 30: Shai Feldman, Israeli Nuclear Deterrence: The Strategy for the 1980s (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982). Opposing Feldman’s views are Avner Yaniv, Deterrence Without the Bomb: The Politics of Israeli Strategy (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1987); Yair Evron, Ha’dilema Ha’Garinit Shel Israel [Israel’s Nuclear Dilemma] (Tel-Aviv: Ha’kibutz Ha’meuhad, 1987); and Yehezkel Dror, Grand Strategy, 139-150. Back.

Note 31: Quoted in Arian, Talmud, and Hermann, National Security and Public Opinion in Israel, 26. Back.

Note 32: See Arnold Walfers, Discord and Collaboration (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1962), chap. 10; see also John A. Vasquez, The Power of Power Politics (London: Frances Pinter, 1983), 48-54. Back.

Note 33: See the definitions of Frank N. Trager and Frank L. Simonie, “An Introduction to the Study of National Security” in Frank N. Trager and Philip S. Kronenberg, eds., National Security and American Society (Lawrence: The University Press of Kansas, 1973), 38; Barry Buzan, “People, States and Fear: The National Security Problem in the Third World” in Edward E. Azar and Chung-in Moon, eds., National Security in the Third World (Hants, UK: Edward Elgar, 1988), 16-17; and Harold Brown, Thinking about National Security (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1983), 4. The idea of secondary national security interest has its roots in Brown’s reference to “the control of borders” as a security goal, from Walfers’s discussion of deviations from the “minimum national core values,” in Discord and Collaboration, 154, and from Bernard Brodie’s definition of vital interests as “those interests against the infringement of which we are prepared to take some serious military action.” See Brodie, “Vital Interests: By Whom and How Determined?” in Tager and Kronenberg, National Security and American Society, 63. Back.

Note 34: See also the discussion of territorial integrity and political independence in Trager and Simonie, “An Introduction to the Study of National Security,” 36-43. Back.

Note 35: Data from Table 1 in Zeev Maoz and Ben D. Mor, Satisfaction, Capabilities, and the Evolution of Enduring Rivalries, 1816-1990: A Statistical Analysis of a Game-Theoretical Model (paper presented at the 1995 annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Chicago, 31 August-3 September 1995), 23-25. Back.

Note 36: The concept of “small” state, as Yohanan Cohen argues, is inherently relative. Demographic and geographical dimensions are not sufficient in order to define states as small. We correctly consider Finland (as it faced the USSR), Czechoslovakia (as it faced Nazi Germany), and Poland (as it faced both) as small states, though Finland controlled vast territory, Czechoslovakia had 14,000,000 citizens, and Poland almost 30,000,000. According to absolute definition, which is based on population or territory, about 20-25 percent of the world’s states are small (Israel is not included in any such list!). Many of these small states are utterly indefensible, and a few of them are situated in hazardous locations such as the Middle East or Southeast Asia. See Yohanan Cohen, Small Nations in Times of Crisis and Confrontation (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 2; the UNITAR Study, Small States & Territories (New York: Arno Press, 1971), 32-33, 36-38; and Gordon W. East and J. R. V. Prescott, Our Fragmented World (London: Macmillan, 1975), 53-55. Back.

Note 37: Data from Alan J. Day, ed., Border and Territorial Disputes (Detroit: Gale Research, 1982); Cohen, Small Nations in Times of Crisis and Confrontation; Robert Schaeffer, Warpaths: The Politics of Partition (New York: Hill and Wang, 1990). Back.

Note 38: See Day, Border and Territorial Disputes, 296-302. Back.

Note 40: Ibid., 222-225. Back.

Note 41: Yair Evron, “Arms Races in the Middle East and Some Arms Control Measures Related to Them” in Gabriel Sheffer, ed., Dynamics of a Conflict (Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press, 1975), 95-135; and J. C. Hurewitz, Middle East Politics: The Military Dimension (New York: Praeger, 1969), 438-88. Back.

Note 42: See Evron, “Arms Races in the Middle East,” 114-15, tables 7-9. See also Hurewitz, Middle East Politics, 448, 450, tables 18, 19. Back.

Note 43: See Segre and Ben-Yaakov, “Powers and Power in Middle East Politics” in Sheffer, Dynamics of a Conflict, 27-36, esp. 30-32. Back.

Note 44: Zeev Maoz, “The Evolution of the Middle East Military Balance, 1980-1994” in Ephraim Kam, ed., The Middle East Military Balance (Jerusalem: JCSS-The Jerusalem Post, 1996), 66-92, esp. 69, 72, 80. The study includes both Iraq and Iran in Israel’s “reference group.” Back.

Note 45: See, for example, the discussion in Avraham Tamir, Hayal Shoher Shalom [A Soldier in Search of Peace] (Tel-Aviv: Edanim, 1988), 227-28, 234. Back.

Note 46: For a similar approach see Cohen, Small Nations in Times of Crisis and Confrontation, 2. Back.

Note 47: Colin S. Gray, for example, notes that for the Arabs to keep Israel as an enemy has the advantages of promoting inter-Arab unity, diverting domestic pressures elsewhere, and avoiding the threat of leaving the scene for full blown inter-Arab rivalry. See “Arms Races and their Influence on International Stability, with a Special Reference to the Middle East” in Sheffer, Dynamics of a Conflict, 68-69. For a study of inter-Arab discord (and collaboration) see Alan R. Taylor, The Arab Balance of Power (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1982). For an analysis of the Arab-Israeli balance of power that includes consideration of different Arab coalitions, see Alouph Hareven, War and Peace (Hebrew) (Jerusalem: Dvir, 1989), 439-48. Back.

Note 48: Jerome Slater “A Palestinian State and Israeli Security,” Political Science Quarterly 106 (Fall 1991): 411-429, esp. 419-20; and Zeev Maoz, “Regional Security in the Middle East: Past Trends, Present Realities and Future Challenges,” The Journal of Strategic Studies 20 (March 1997): 11-15. Slater notes that Israel faces a reduced threat and lower probability of an Arab attack due to political and military factors that only intensified after 1990 as a result of the Soviet decline and the defeat of Iraq in the Gulf War. These factors include a decreased Arab hostility, the strong Israeli nuclear deterrence, and the American commitment to Israel. Back.

Note 49: Maoz uses as an indicator for severity the rate of military and civilian fatalities that resulted from interstate violence. See “Regional Security in the Middle East,” in particular table 1, 11. Back.

Note 50: Avner Yaniv, “Hartaa Ve’hagana Ba’estrategia Ha’Israelit” [Deterrence and Defense in the Israeli Strategy] in Medina, Mimshal Ve’Yehasim Ben-Leumiyim 24 (1985), 56; and Tamir, Hayal Shoher Shalom, 362-3. Back.

Note 51: On Israel’s arms exports, see Aaron Klieman, Israel’s Global Reach (Washington, DC: Pergamon-Brassey’s, 1985), esp. 29-69 and 149-166. Back.

Note 52: The case in favor of Israel has been made by William V. O’Brien, Law and Morality in Israel’s War with the PLO (New York: Routledge, 1991), 148-271; Esther R. Cohen, Human Rights in the Israeli-Occupied Territories, 1967-1982 (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1985). Back.

Note 53: See Michael Waltzer, Just and Unjust Wars (New York: Basic Books, 1977); James T. Johnson, Just War Tradition and the Restraint of War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981); Thomas Nagel, “War and Massacre” in Charles R Beitz, Marshall Cohen, Thomas Scanlon, and A. John Simmons, eds., International Ethics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985), 53-74; George Mavrodes, “Conventions and Morality of War” in ibid., 75-89; and O’Brien, Law and Morality in Israel’s War with the PLO. Back.

Note 54: Waltzer, Just and Unjust Wars, 36. Back.

Note 55: See Thomas Nagel, “War and Massacre” in Charles R. Beitz et al., International Ethics, 54-56. Back.

Note 58: Waltzer, Just and Unjust Wars, 41. Back.

Note 59: Nagel, “War and Massacre,” 63. Back.

Note 60: See the discussion in Waltzer, Just and Unjust Wars, 151; and George Mavrodes, “Conventions and Morality of War” in Beitz et al., International Ethics, 76. Back.

Note 61: See the discussion of legitimacy within the “double effect” in George Mavrodes, “Conventions and Morality of War,” 77; and Waltzer, Just and Unjust Wars, 151-54. Back.

Note 62: See O’Brien, Law and Morality in Israel’s War with the PLO, 91. Back.

Note 63: See Ben-Eliezer, Derech Ha’Kavenet [Through the Gun-Sights], 252-68. Back.

Note 64: See Morris, Israel’s Border Wars, 1949-1956, esp. 227-62; Yigal Elam, Memalei Ha’pkudot [The Executors] (Jerusalem: Keter, 1990), 53-70; Eitan, A Soldier’s Story, 163-64; and Yediot Araronot, weekend supplement, 11 April 1997. Back.

Note 65: See Ze’ev Schiff and Ehud Ya’ari, Israel’s Lebanon War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984), 132-50, 195-229, esp. 211-12. Back.

Note 66: See the continuing reporting of journalist Gideon Levi in Ha’aretz, successive issues of Amnesty International Report (London: Amnesty International Publications); current reports, case studies, annual reports, and other publications of B’tselem, The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories (Jerusalem); and Ilan Peleg, Human Rights in the West-Bank and Gaza (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1995). Back.

Note 67: On the state of regulation of whatever is not included firmly within the Jus in Bello, as it applies to nonnational armies, see James Turner Johnson, Just War Tradition and the Restraint of War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), 59-69, esp. 64. Back.

Note 68: Yediot Aharonot, weekend supplement, 26 July 1996. Back.

Note 69: On French conduct, see Pierre Vidal-Naquet, Face a la raison d’etat (Paris: E©ditions La De©couverte, 1989); Rita Maran, Torture: The Role of Ideology in the French-Algerian War (New York: Praeger, 1989). Back.

Note 70: Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing, 1979). Back.

Note 71: See Ze’ev Schiff, “Israel After the War,” Foreign Affairs 70 (Spring 1991): 19-33; Mark Heller, “Coping with Missile Proliferation in the Middle East,” Orbis 35 (Winter 1991): 15-28; and Reuven Pedhatzur, “Theater Missile Defense: The Israeli Predicament,” Security Studies 3 (Spring 1994): 521-70. Back.

Note 72: See Arian, Talmud, and Hermann, National Security and Public Opinion, 24-26. Back.

Note 73: See Tamir, A Soldier in Search of Peace, 104-105, 334; and Ariel Levite, Ha’doctrina Ha’tzvait shel Israel: Hagana Ve’hatkafa [The Israeli Strategic Doctrine: Defense and Offense] (Tel-Aviv: Ha’kibutz Ha’meuhad, 1988), 109. Back.

Note 74: On past changes, see Dan Horowitz, Ha’kavua Ve’hamishtane Be’tfisat Ha’bitachon Ha’Israelit [The Constant and the Changing in Israel National Security Perception] (The Leonard Davis Institute for International Relations, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1982); and “Israel’s War in Lebanon: New Patterns of Strategic Thinking and Civilian Military Relations” in Moshe Lissak, ed., Israeli Society and Its Defense Establishment (London: Frank Cass, 1984), 83-102. On recent changes, see Efraim Inbar, “Contours of Israel’s New Strategic Thinking,” Political Science Quarterly 111 (Spring 1996): 41-64. On long-term changes in public opinion, see Asher Arian, Israeli Security Opinion, February 1996, JCSS Memorandum no. 16 (Tel-Aviv: Tel-Aviv University, 1996), 10. Back.

Note 75: Dror, Grand Strategy, 97. Back.

Figure 1:The Sources, Structure, and Consequences of the Israeli Image of National Security Exceptionalism

Table 1: Ratios of Basic Power-Indicators of Selected Conflict Dyads (rounded figures)