Foreign Policy

Winter 1998–99

What Russia Can Learn from Cuba

By Ana Julia Jatar-Hausmann *

For most purveyors of conventional wisdom in the early 1990s, the collapse of the Soviet Union meant the imminent fall of Castro’s Cuba. Few thought that the Western Hemisphere’s final communist stronghold could survive without subsidies, aid, and preferential trade treatment from the Soviet bloc. That conviction deepened with Cuba’s failure to follow Russia down the path of market democracy.

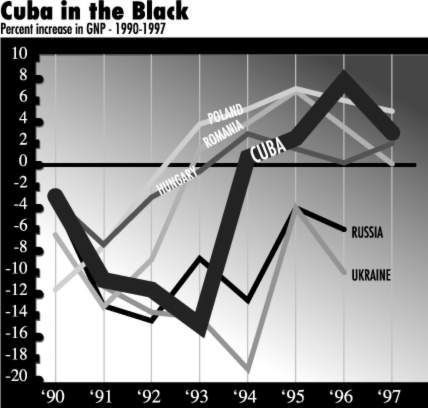

Nevertheless, to the surprise of all, disappointment of many, and joy of a few, Russia today is the world’s leading economic charity case, and Cuba has become the lone soldier of state socialism. Even as Russia’s GDP shrunk by a staggering 42.5 percent between 1989 and 1997, Cuba’s economic output—after plunging initially by 35 percent between 1989 and 1993—has managed to recover and grow every year since then. What happened? Why has Cuba “succeeded” where Russia has “failed?”

Russia’s decision to forsake communism for market democracy won it badly needed political and economic support from the United States and its partners in the Group of Seven. Cuba, in contrast, confronted a post-Soviet world that was more bleak than brave. Its trading relationships with other members of the former Soviet economic bloc—which accounted for 87 percent of Cuba’s trade—rapidly disintegrated, as did its annual Soviet subsidy, which averaged $2.1 billion for three decades. And instead of multilateral assistance, Cuba has faced unilateral sanctions from the United States.

The resulting economic free fall between 1990 and 1993 opened the door to reform in Cuba. As Fidel Castro said in July 1993, “[L]ife, reality ... forces us to do what we would have never done otherwise ... we must make concessions.” Cuba’s economic initiatives, launched in mid-1993-and implemented in fits and starts during the past five years-have aimed to increase the flow of foreign exchange, reduce government expenditures, and increase the supply of goods and services. Moreover, these goals have had to be achieved without jeopardizing the political continuity of the regime.

Cuba legalized dollar holdings, which enabled Cubans to spend dollars freely for the first time and thereby spur the flow of remittances, and created state-owned dollar retail stores. The government also encouraged foreign investment in a bid to attract hard currency. In May and June of 1994, Cuba set out to reduce the fiscal deficit by cutting subsidies to state enterprises; jacking up prices on cigarettes, gasoline, alcohol, electricity, and other goods and services; and—for the first time since the revolution—establishing a tax system. To increase the supply of food, big state-owned farms were converted into cooperatives whose members set their own goals and shared in profits. Cuba also legalized self-employment in more than 170 different occupations, collecting fees and taxes from the self-employed.

Since the implementation of reforms, Cuba’s economy has been growing and is likely to continue to do so. Its GDP has expanded by 15 percent since 1994, with 4 percent growth expected for 1999. Despite the distorted official exchange rate of 1 peso per dollar, the black market rate has stabilized at 19 pesos per dollar, and the fiscal deficit has been kept at 2 percent of GDP. Of course, as the Cuban and Russian transition experiences each show, searching for the invisible hand is inherently difficult. What lessons can be drawn from the Cuban experience?

First, introduce fiscal austerity measures before exchange rate liberalization. Prior to balancing its budget, Russia freed exchange rates and induced hyperinflation. Cuba, however, initiated an aggressive and unpopular fiscal adjustment and has not yet unified the exchange rate, allowing the dollar to stabilize.

Second, accept that abandoning socialism will inevitably result in economic decline, at least temporarily. Unlike Russia, Cuba has chosen to create opportunities for investment and growth before dismantling its existing system.

Third, when privatizing inefficient public enterprises, change the incentive structure before the ownership structure. Russia’s laissez-faire capitalism has allowed managers to exploit enterprises under their control. Absent a strong enforcement capacity, Mafia-like groups have come to dominate important sectors of the economy. In Cuba, the alliance between government and foreign investors has created market-oriented incentives while keeping out organized crime.

Fourth, harness military power behind reforms. In the absence of market institutions, the military can provide an efficient alternative mechanism for coordinating business during the transition. But as the recent experience of China shows, weaning the military off its reliance on commercial ventures can be a delicate political task.

There is one central lesson, however, that Russia has for Cuba, even if it is expressed in the negstive: Avoid total-victory scenarios. Seven years after Boris Yeltsin stood atop a tank to symbolize the end of Russian communism, the finality of the U.S. triumph seems much less obvious. Resolving the continuing civil war between Cuba’s exiles and its inhabitants is bound to prove more successful than attempting to achieve “total victory,” as the Russian experience suggests. If an armistice took place that eliminated the potential for outright victory by either side, the reform process in Cuba could naturally continue building a country that is more prosperous and more democratic.

|

| Sources: World Tables, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995). Poland: The Path to a Market Economy (Washington: IMF, October 1994). Banco Nacional de Cuba Monthly Bulletin of Statistics, (New York: United Nations, 1998) |

An Exceptionally Blunt Instrument

Cuba’s Long-Distance Civil War

Further Reading

Anders Åslund’s How Russia Became a Market Economy (Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 1995)

Julio Carranza Valdés, Luis Gutiérrez Urdaneta, and Pedro Monreal González’s Cuba: Restructuring the Economy: A Contribution to the Debate (London: Institute of Latin American Studies, University of London, 1996)

Jorge Castañeda’s Compañero: The Life and Death of Che Guevara (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997)

Evelyn Cohn and Alan Berlin’s “European Community Reacts to Helms-Burton” (New York Law Journal, August 4, 1997)

Cuba in the Americas: Breaking the Policy Deadlock, the second report of the Inter-American Dialogue Task Force on Cuba, (Washington: IAD, September 1995)

“Cuba Survey” (The Economist, April 1996)

Jorge Dominguez’s “U.S.-Cuban Relations: From the Cold War to the Colder War” (Journal of Inter-American Studies and World Affairs, Fall 1997)

La Economia Cubana: reformas estructurales y desempeño en los noventa (Mexico City: CEPAL, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1998)

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s Transition Report 1995, 1996, and 1997 (London: EBRD)

Maurizio Giuliano’s El Caso CEA, Intelectuales e Inqusisidores en Cuba, Perestroika en la Isla? (Miami: Ediciones Universal, 1998)

“Key Cuba Foe Claims Exiles’ Backing” (New York Times, July 12, 1998)

Ana Julia Jatar-Hausmann’s The Cuban Way: Communism, Capitalism and Confrontation (West Hartford: Kumarian Press, forthcoming)

Carmelo Mesa-Lago, ed., Cuba after the Cold War (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh University Press, 1993)

Jorge Pérez-Lopez, ed., Cuba at a Crossroads: Politics and Economics after the Fourth Party Congress (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1994)

OECD Economic Surveys: Russian Federation (Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 1997)

Tad Szulc’s Fidel: A Critical Portrait (New York: Avon Books, 1987)

Endnotes

*: Ana Julia Jatar-Hausmann is a senior fellow at the Inter-American Dialogue in Washington and author of The Cuban Way: Capitalism, Communism and Confrontation (West Hartford: Kumarian Press, forthcoming). Back.