|

|

|

|

Beverly Crawford and Ronnie D. Lipschutz, (editors)

International and Area Studies Research Series/Number 98

University of California, Berkeley

1998

Nationalism: Rethinking The Paradigm In The European ContextNationalism: Rethinking The Paradigm In The European Context

Andrew V. Bell-Fialkoff and Andrei S. Markovits

Introduction

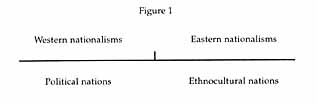

Among numerous typologies of nationalism few have won as widespread an acceptance as the division into Western and Eastern varieties. This dichotomy is based on a distinction between political and cultural nations introduced by Friedrich Meinecke at the beginning of this century (Krejčí and Velimský 1981: 22). It was further elaborated by Hans Kohn and Emerich Francis, whose “demotic” and “ethnic” nations fit the same paradigm.

Francis defined the ethnic (or “cultural”) nation as an “ethnic society which is politically organized in a nation-state and is exclusively identified with it” (1976: 387). This type of nation is based on jus sanguinis. His demotic (or “political”) nation was a demotic society coextensive with a sovereign state. (He defined demotic society as a “complex and ethnically heterogeneous society that is politically organized in such a way that all its members are, through special institutions, linked directly and without the mediation of subsocietal units to the central authority” [1976: 383]). The integration of such society is based on democratic government and cultural homogeneity (1976: 387); its identity is derived from jus soli.

The division has the advantage of simplicity and even a certain elegance (see Figure 1), but although basically sound, it has significant drawbacks. First, it reflects almost exclusively the European situation, virtually ignoring nationalisms elsewhere. The non-European nationalisms are usually assigned to the “Eastern” subdivision without much regard for the vast differences between a quasi-racial Japanese nationalism and the integrative nationalisms of Latin America. Even in Europe proper one finds “Eastern” nationalisms and, as will be demonstrated in this paper, “Western” nationalisms in the East.

Another drawback is that, in Anthony Smith’s words, it “assumes a necessary correlation between types of social structure and philosophical distinctions” (1971: 197). In other words, the social composition of a given society acquires a predictive role in the sense that certain social strata will supposedly generate a certain type of nationalism. Actually, such interrelationships are extremely complex and cannot be considered fully deterministic. Also, some nationalisms, such as Russian, Turkish, or Tanzanian, combine voluntaristic/subjectivist elements of the Western variety with the organic/objectivist elements of the Eastern kind. Finally, the two categories are called upon “to do too many jobs . . . cover too many levels of development, types of structure and cultural situations” (ibid.). They end up being cumbersome.

We believe that a reevaluation of the traditional classification of nationalisms is called for. Specifically, we think that the Western/Eastern dichotomy does not sufficiently emphasize the more fundamental issues: the interaction between ethny and state and the individual’s relationship to both, especially the mode of his/her incorporation. Our paper will build upon the foundations laid by R. D. Grillo in his work on the interrelationship between “nation” and “state” and by Pierre van den Berghe on the mode of incorporation as it relates to ethnic exclusivity/inclusivity.

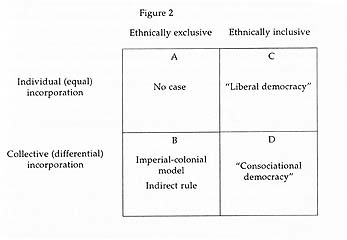

In Grillo’s scheme the distinct varieties of nationalism are the natural outcome of two complicated processes which he calls (1) the “ethnicization of the polity” (the “demotic” type in Francis’s terminology or the “statist” model in Anthony Smith’s), where a state “constructs” a nation from often heterogeneous elements, and (2) the “politicization of ethnicity” (the “ethnic” model in both terminologies), where an ethnic group strives for and achieves statehood (Grillo, ed. 1980: 7). We will also incorporate van den Berghe’s ideas concerning the correlation of ethnic monopolization of power (ethnically exclusive/inclusive) with the mode of incorporation (individual or collective) (see Figure 2, based on Schema I in van den Berghe 1981: 79). But we will redefine his postulates somewhat since individual incorporation, which typifies demotic nations, is inherently inclusive because it strives to assimilate all citizens of a given polity to the “official” culture. By contrast, collective or corporate conceptualization of ethnicity is by definition exclusive since it insists on descent as the criterion of admissibility.

This paper will continue both lines of research. Specifically, we discard the inadequate division of nationalisms into Western and Eastern varieties. Instead we will endeavor to show that virtually all types of nationalism can be found in Western as well as Eastern Europe—that it is the presence or absence of the state and the mode of incorporation which determine the nature of a particular nationalism. Our task, therefore, is to offer a new typology which takes into account both sets of variables.

We are fully aware of the fact that our paper entails a categorization in addition to an analysis. As such, all concepts developed in it are by their very nature static. But in an exercise of classification and comparative delineation stasis is not only acceptable, but it is in fact desirable. An inherent aspect of any classificatory scheme is that all concepts described therein are by necessity “ideal types” in the Weberian sense, meaning that none of them exist in their purity in the real world. But for heuristic purposes such ideal types are very useful in delineating complex realities. Such will be the case with all our categories in this paper.

We will start with definitions and categorization, continue with the traditional representation of both types of nationalism, present empirical examples of our own typology in Western and Eastern Europe, and offer our conclusions as to the validity of both typologies as well as the ongoing transformation of nationalisms which is now occurring in Western Europe. (Nationalisms of Eastern Europe are not affected by a similar transformation; they are developing within traditional parameters of the “Eastern” model.)

Typology/Categorization of Nationalisms

There are several variables determining the type of nationalism. First, the role of the state. Nationalisms enunciated and promoted by existing states will be designated as statist. These nationalisms define a nation as a territorial-political unit. Where the state is absent, the nationalism is nonstatist by definition. Proponents of the nonstatist variety see the nation as a politicized ethnic group bound together by common culture or, as anthropologists would put it, delimited by “cultural markers.” These nationalisms usually start as cultural movements.

Second, the mode of incorporation. It can be based on either the individual or the corporate entity. Here we have several subvariables. We will call nationalisms which stress individual freedoms and responsibilities of political citizenship Lockean since Locke was among the earliest proponents of individual freedom and of the legitimacy of political rule emanating from the consent of the governed. 1 As has been stated earlier, a Lockean nationalism promotes the incorporation of each citizen on an individual basis—i.e., it opens the doors to advancement and promotion to any member of a given polity as long as s/he learns the state language and adopts the state culture. In that sense it is inherently inclusive because it accepts all citizens regardless of their origin.

Conversely, we will call Herderian those nationalisms which restrict full membership to persons of a particular origin, language, and cultural diacritica, thereby excluding outsiders. 2 They are inherently exclusive. Although individuals can and do cross ethnic boundaries into Herderian entities (e.g., through marriage), in principle incorporation is based on descent and is therefore collective or corporate in character. In fact, instead of calling it “Herderian incorporation,” it would be better to refer to it as “ethnic eligibility.”

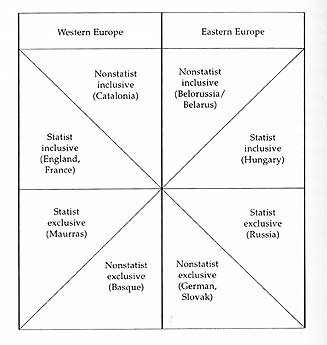

To avoid cumbersome designations we will divide nationalisms into statist and nonstatist, depending on the role of the state, and Lockean-inclusive or Herderian-exclusive to indicate the mode of incorporation and ethnic inclusivity/exclusivity. Figure 3 offers a graphic representation of our typology. We retained the basic geographical division into Western and Central/Eastern Europe. However, we attempted to find all four varieties—statist/nonstatist and Lockean-inclusive/Herderian-exclusive—in both areas. The statist Lockean-inclusive variety in the West will be represented by England and France. Catalonia will provide an example of the Lockean-inclusive nonstatist type in the same area. In the East, Hungary fits the Lockean-inclusive statist kind while Belorussia will supply an example of the Lockean nonstatist variety.

With Herderian nationalisms we will have to start in the East since it is this part of Europe that has been traditionally considered their birthplace. Also, the statist/nonstatist order we followed in examining Western Europe will be reversed since the Herderian type develops among ethnies which do not possess a sovereign state of their own. Thus Herderian nationalisms of the nonstatist kind in the East will be represented by German and Slovak nationalisms, and Russian will provide an example of the Herderian statist variety. In the West, Basque nationalism corresponds to the Herderian nonstatist type, while the “integral nationalism” of Charles Maurras in France fits, with some allowances, the mold of the Herderian statist kind. But first we must turn to brief overviews of Lockean and Herderian nationalisms.

The Traditional Representation of Lockean Nationalism

In Western Europe nationalism focused on the individual and saw the state as a commonwealth based on the freely given consent of the governed. As Locke wrote in his second “Treatise on Civil Government,” “Nothing can make any man [a member of a commonwealth] but his actually entering into it by positive engagement, and express promise and compact” (cited in Greenfeld 1992: 400). Thus in Hans Kohn’s words, “The individual, his liberty, dignity, and happiness [became] the basic element of all national life [while] the Government of a nation was a moral trust dependent upon the free consent of the governed” (Kohn 1965: 18).

Historically this was a highly unusual line of reasoning. The emphasis on the individual, at the expense of the state as a collective institution, could develop only because in the West the modern state emerged as a consequence of a struggle between the crown and the landed aristocracy. The aristocracy, entrenched in provincial assemblies, claimed to champion “national liberties” and “national rights,” which, in the context of the time, meant aristocratic privileges since the concept of “nation” did not include the lower classes.

The crown, forced to look for allies, found them in the well-to-do strata of the Third Estate. When it won, the crown proceeded to build a centralized absolutist state which required a code of communication accessible to all. In other words, the state needed a language which could be learned or imposed only through standardized education, as well as a streamlined bureaucracy and administration. The introduction of German as the language of government administration by Joseph II (Kann 1950: 53) in relatively backward Austria shows that this constituted a development which was not limited to Western Europe. As Latin lost its preeminence—in France as early as 1539 (the decree of Villers-Cotterêts)—and printing spread, it facilitated the development of vernacular literatures, which consolidated closely related dialects into closed fields of communication (in the Deutschian sense) inaccessible to outsiders. 3 This development was further enhanced by the “hardening” of borders, another consequence of the centralized state, within which a sense of commonality could better develop. (Before, frontiers were porous and permeable, not at all the linear barriers we know today; see Braudel 1986: 298).

Finally, the concept of time changed as well. In medieval Europe,

Time, calendar, and history were reckoned by the Christian scheme. . . . Current events were recorded in relation to religious holidays and saints’ days. . . . Hours of the day were named for the hours of prayer (Tuchman 1978: 54).

In other words, time was repetitive, circular, and suffused with Christian symbolism. With the Reformation this was lost. Instead, a person turned into a “sociological organism moving calendrically through homogeneous time” (Anderson 1983: 31). Thus the “script language, monarchy, temporality in which cosmology and history were indistinguishable” (Anderson 1983: 40) all changed. Anderson sees the origins of national consciousness in the interplay of decreasing linguistic diversity, technology (book printing), and capitalism, which created monoglot mass readership. 4

Politically the absolutist state hinged on the king’s divine right. But it was undermined by the Reformation almost as soon as the tendency toward absolutism appeared. Already Ulrich Zwingli and Jean Calvin insisted that the government had to conform to the laws of God. Zwingli’s successor, Henrich Bullinger, openly asserted the right to resist bad government and revolt against tyranny (Kohn 1944: 137). Once kingship was stripped of the divine right, the person of the king lost its sacred character and became a mere mortal who could be removed or even executed. This would eventually lead to the beheading of Charles I and then Louis XVI.

The delegitimation of the divine right left a void in the conceptualization of the body politic. It was eventually filled by the notion of “the people,” which was redefined as a nation by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. His nation was based on the sovereignty of the people (the “general will,” in his parlance) and full rights for each member, at least in theory. In such a nation, nationalism was the expression of the free individual’s free will. This concept was inherently anti-monarchical, anti-feudal and anti-aristocratic. It could fully develop only in the relatively open, rapidly developing societies of Western Europe and North America whose elites believed in the Enlightenment and Reason, at least in principle, and proclaimed liberty, equality, and fraternity, at least in theory. In short, it was possible only in societies which were built on constitutionalism, parliamentarism, participatory democracy, and what we would nowadays call pluralism.

Since the bourgeoisie was the rising element in these societies—economically, socially, and politically—bourgeois values—individualism, liberalism, tolerance—permeated Western nationalism. Politically and socially these attitudes were translated into the idea of a social contract, the legal concept of citizenship, the principle of individual rights and legal equality. Moreover, since nationalism in the West developed within well-established states, it was subjected to all the constraints which West European political order imposed on the state itself (Fishman 1973: 24–25). And since it was based on political citizenship which could be acquired, it was inherently inclusive. Historically it integrated ever wider masses of people into the politically defined nation, usually led by the middle classes, who sought allies in their struggle against aristocratic privilege. First with the crown against the aristocracy, then with the masses against the absolutist monarchy, the bourgeoisie mobilized the peasantry, the artisans, and the nascent industrial proletariat, transforming them into a new, integrated community which eventually coalesced into the nation.

The Traditional Representation of Herderian Nationalism

If certain characteristics of Lockean thought can be harnessed to depict an ideal type of Western nationalism, then a parallel construct using Herder’s ideas might be useful in delineating what has come to be known as Eastern nationalism. Unlike Locke, who had merely enunciated certain principles which were incorporated into the foundations of West European nationalisms, Herder was a theoretician of a new brand of nationalism. This is not to say that he was a nationalist in the modern sense. To him nationality was not a political or biological but a spiritual and moral concept (Kohn 1965: 31) (which is not to say that he disregarded the role of the state altogether: in his conception the national state was the means through which national characteristics were developed [Ergang 1966: 255]).

Yet Herder was the first to develop a comprehensive philosophy of nationalism. At a time when nationalities were regarded as obstacles on the road to a universal, rational society, Herder believed that nationality was an indispensable building block and “an essential factor in the development of humanity” (Ergang 1966: 248). He saw the ethnic group as an organic unity whose growth was regulated by natural law. The nature of nationality and national character was religious, deterministic, divine. Laws of nature were “thoughts of the Creator,” and each nationality was part of the divine plan in history (Ergang 1966: 250). In Herder’s view, ethnos was an organic growth and at the same time a self-revelation of the Divine. He believed that human civilization lived in its national and peculiar manifestations, not in the Universal. People were first and foremost members of their national communities; only as such could they be truly creative (Kohn 1965: 31). In a curious premonition of the anthropomorphic analogies made popular by vulgar Darwinism a century later Herder thought that after a period of growth each national organism matures and then sinks into senility, making way for others which pass through the same cycle. It was also implied that each national organism had its own national soul (Ergang 1966: 85).

Herder’s cultural polycentrism emphasized folklore, ritual, customs, myth, folk songs, and language—i.e., clues to a people’s collective personality and identity (Smith 1971: 182). Polycentrism is a giveaway of Herderian nationalism: two hundred years later most Russian nationalists are equally polycentric. Thus Ilya Glazunov, a well-known painter and nationalist: “I believe that world culture has nothing to do with Esperanto but is a bouquet of different national cultures” (interview in Vol’noie slovo 33 [1979]; cited in Conquest, ed. 1986: 271).

Herder believed that as the group became a single unit, a being, it acquired a unique personality which found expression in its history, language, literature, religion, customs, art, science, and law. Culture, then, was a product of the group mind (Ergang 1966: 87). Herder was not a racist in any sense. “Notwithstanding the varieties of the human form,”” he wrote, “there is but one and the same species of man throughout the whole earth” (cited in Ergang 1966: 88). “Men are formed only by education, instruction and permanent example” (cited in Ergang 1966: 91).

While Rousseau believed that legislation and common will can turn people into a community, Herder subscribed to the view that nature was “the great architect” of human society (cited in Ergang 1966: 95). His bitterness and invective were directed against “soulless cosmopolitanism,” which is somewhat reminiscent of our modern dread of anomie. 5 Herder, however, equated this pernicious cosmopolitanism with French influence, especially French education, a rather prevalent attitude in the Germany of his time. In denouncing the French, Herder overstepped the line which separates patriotism from nationalism or even chauvinism.

In many respects Herder was the spiritual founder and the intellectual cornerstone of German nationalism. His view of language as an outstanding mark of nationality, a reflection of its thought-life (Ergang 1966: 105); his belief that each nationality has a mission to develop its national characteristics and cultivate its national individuality (Ergang 1966: 112); his opinion that culture must be national in form and content (Ergang 1966: 251) (later reworked by Stalin to become “national in form, socialist in content”)—all testify to the extremely important role played by Herder in the rise of German and subsequent Herderian nationalisms. In this and in many other respects he was the precursor of Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Giuseppe Mazzini, František Palacký, Lajos Kossuth, Jan Kollár, Dositej Obradovi

Virtually all Herderian nationalisms go through several easily discernible stages. At first, a few intellectuals redefine ethnicity as a category of classification; then they have to spread their ideas among the general population and mobilize it in order to confront the state apparatus controlled by the dominant ethny; finally, after a period of struggle, their ethny either gains complete independence or settles for a limited sovereignty in a federal or consociated system.

The first stage, the redefinition of ethnicity, requires an intelligentsia. That is not to say that peasants or artisans were unaware of ethnic or religious differences. Anti-Jewish violence in medieval Europe and interdenominational massacres in France and Germany during wars of religion prove otherwise. Nor should we assume that peasants could not organize themselves: peasant wars in England, France, and Germany (and later Russia) show they could. However, only the intelligentsia with its intellectual expertise and the ability to conceptualize could make ethnic differences a major category of classification and then mobilize various interest groups in defense of an “imaginary community.” Societies where the upper classes preferred an alien language and culture facilitated the spread of Herderian nationalism. Such preferences reduced the reading public, relegated ethnic intellectuals to a secondary position, and sent thousands of ambitious ethnic intellectuals into an alien cultural milieu. In this situation language became a matter of paramount importance. And if the country was militarily weak and disunited, as was the case in the Germanies and Italies, or subject to ethnically alien rulers, as was the case everywhere else in Eastern Europe, or even if it simply suffered from a complex of cultural inferiority, as was the case in Russia, all these factors provided a strong stimulus to worshipping strength and unity.

Since even the most rabid ethnic nationalists could not simply deny the superiority of the civilization which they rejected, they could only fall back on the innate goodness of their ethny. Thus the wholesomeness, the manly virtues of their own people had to be contrasted with the degenerate character of the “western” neighbor. And westerners in general had to be represented as false, effeminate, and phony—in short, contemptible. Or as an old Flemish saying goes, “Wat wals is, vals is” (Whatever is Walloon is false). Ironically these accusations, first hurled against the French by the Germans, were later used by Slavs against Germans as the bacilli of Herderian-type nationalism penetrated further east.

Once the differences had been recognized, proto-nationalist intellectuals had to indoctrinate the people and look for allies. Although these intellectuals often found themselves close to the centers of power—as teachers of rulers’ offspring, for example—they were powerless themselves and could not effect fundamental changes on their own. Thus their indoctrination efforts were inevitably bifurcated, directed at the ruling elite on the one hand, at the lower classes on the other.

In the feudal and semifeudal absolutist states of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, where the bourgeoisie was numerically weak and politically even weaker, the nascent nationalistic intelligentsia sided with whatever allies it could find: the local gentry (as in Poland and Hungary) or even the peasantry (as in Slovenia, Bulgaria, and Serbia). While in the West nationalism developed as a political expression of the rising middle classes within the established states, in the East it developed as a cultural movement in societies which had not for the most part experienced Renaissance, Reformation, or Enlightenment.

Familiar only with authoritarian political structures, Herderian nationalism developed a strong authoritarian bent, just as Lockean-type nationalism bore the imprint of Western liberal tradition. In the West individualism suffused nationalism. In the East nationalism promoted communalism. More often than not, such communal nationalism found a natural ally in forces of reaction. This was particularly true of “satisfied” ethnic nationalism—i.e., nationalism which had achieved statehood, like Hungarian nationalism after the Compromise of 1867. Others—Croatian nationalism, for example—could flip-flop, siding with reactionary Vienna against revolutionary Hungary or with Hungary against Vienna, depending on the situation. This shows that much in nationalism’s behavior and configuration was circumstantial and not the result of some intrinsic reactionary essence.

Intellectuals espousing Herderian-type nationalism tried to overcome their strong complex of inferiority by instilling a sense of mission and messianism. This was facilitated by the fact that many contemporary (nineteenth- and early twentieth-century) East European cultures were still suffused with religious messianism and Christian universalism, an inheritance of the Middle Ages. As Nikolai Berdyaev wrote in his comments on the Russian Revolution,

The Russian people are passing from one medieval period into another. . . . The workman is not at all inclined to pass from Christian faith to enlightened rationalism and skepticism; he is more inclined to go over to a new faith and a new idol-worship” (Berdyaev 1960: 39).

Most Russian “workmen” passed from Christianity to “prophetic” Marxism to nationalism. This explains much of the fanaticism and the dogma of early Soviet communism and Stalinism and the spread of extreme nationalism in post-Communist Russia, which surprised many observers. In much of Eastern Europe, where nationalism had made earlier inroads and where (Soviet) communism was “imported” and imposed, a large proportion of the proletariat bypassed Marxism altogether. In these countries nationalism proved to be a potent antidote to Marxism, and when the Soviet domination collapsed (or was withdrawn), nationalism reappeared as a major political force.

Romantic historicism played a major role in this turnaround. As a rule, Herderian-type nationalisms idealized the past and turned it into a cornerstone of national regeneration. The idea of nationhood centered around the folk community imagined as a healthy, manly peasant society free of degenerate Townsman and Foreigner (often equated since in many areas towns were populated by people of different ethnic origin—e.g., Germans and Jews). Xenophobic and chiliastic, Herderian nationalisms sought to recreate the imagined past in the future.

Until 1848 Herderian nationalism stressed collaboration of peoples against monarchs and saw its mission in the fight for freedom and constitutionalism (Kohn 1955: 39), which made it run on a track parallel to that of the Lockean-type nationalism. However, after 1848 it turned increasingly to the glorification of the martial spirit, worship of national heroes and their deeds in war. In a sense, this is the year when Herderian nationalism came of age: from here the pedigree becomes unmistakably “Eastern,” and the line of development points increasingly in one direction: that of political intolerance and authoritarianism.

Above we delineated the position that Lockean-type nationalism is based on political citizenship in a preexisting state which promotes individual rather than communal incorporation and determines the inclusive character of Lockean nationalism. To test these assumptions we will now look for (a) statist Lockean and (b) nonstatist Lockean nationalisms in the West, as well as (c) statist Lockean and (d) nonstatist Lockean nationalisms in the East. England and France will serve as examples for case (a).

English Nationalism

United under one government since at least 1017, in possession of a common literary language and venerable historical traditions, England is considered a classical representative of Lockean-type nationalism. Of particular importance is the fact that its Parliament developed as a territorial, not a tribal, assembly (Snyder 1976: 73–74).

However, as one looks closer, one discovers features which are unexpected in a Lockean nationalism. First, English nationalism arose out of a religious matrix (Kohn 1965: 16–17), which is a Herderian trait. It was the break with Rome in 1534 that laid the Protestant foundations of English nationalism. These were reinforced by the persecution of Protestants in Queen Mary’s reign; in Liah Greenfeld’s words, “Religion and national sentiment became identified” (1992: 66). Then, under Puritan influence, the three main tenets of Hebrew nationhood were revived: the idea of a chosen people (this goes back to Milton), the Covenant, and the messianic expectancy.

Another Herderianism is only a partial acceptance of the people of the Celtic fringe. According to Geoffrey Gorer, within the internal English context, people of the Celtic fringe are regarded as un-English, almost as foreigners (cited in DeVos and Romanucci-Ross 1975: 156–72). Here there is a clearly maintained difference between being British (no one denies that the Welsh are British) and English (which they are not).

Given the presence of clearly Herderian traits in a quintessentially Lockean nationalism, what, we may ask, separates it from purely Herderian nationalisms? The important difference, according to Hans Kohn (1965: 18), is that the individual, his liberty, dignity, and happiness were the basic elements of national life. This presupposes a voluntary accession to the political community. Indeed as it gradually expanded its political franchise in the nineteenth century, English nationhood incorporated broad masses within an existing state into a cohesive whole. But, we may ask, is voluntary incorporation indispensable? Is Lockeanism possible where coercion is applied? Such indeed was often the case in France.

French Nationalism

Like its English counterpart, French nationalism is an uneasy melange of Lockean and Herderian traits. The cultural heritage of French national identity, its literary language, the continuity of history and statehood go back to at least the twelfth century.

French nationalism is unique in that we can pinpoint the beginning of Lockeanization with precision: 1254. This was the year when the king’s title was changed from rex Francorum to rex Franciae (Greenfeld 1992: 92), and the definition of Frenchness from jus sanguinis to jus soli. From that moment French identity was defined by an increasingly powerful and centralized state. The contents of identity could change drastically. In fact it metamorphosed from being a religious community, the eldest daughter of the Church, ruled by the “most Christian king” (Greenfeld 1992: 93), to a political community which owed its allegiance to the “people,” which was redefined to include the whole population of France. The state and the people of France fused into a new notion of the “nation” (imported from England, according to Greenfeld 1992: 155). The new entity was increasingly perceived in opposition to the king and, eventually, the aristocracy, which did not enter into the new Covenant, to the extent that it came to be seen as an alien race which had descended “from the forests of Franconia” (Abbé Sieyès; cited in Greenfeld 1992: 172).

Through all these metamorphoses “Frenchness” was solidly anchored within the structures of the state. This does not mean that France was a homogeneous entity. Its unity was imposed from above and concealed deep fissures in French society. In 1790 Abbé Grégoire found that while three-quarters of the population knew French, only about one-tenth could speak it (Johnson in Teich and Porter, eds. 1993: 52). In the south (langue d’oc) most people did not even understand the language (Braudel 1986: 81). And Eugen Weber showed that the French peasantry, especially in the south, did not join the major currents of national life until this century’s interwar period (Weber 1976).

But at least the framework of the state was already in place when French nationalism was born. Only one thing was left to do: turn all the inhabitants of the state into Frenchmen. This was the task of universal public education and the army, which spread the state language and implanted feelings of patriotism in the hearts of the citizens and their children.

The imposition of French was often implemented by oppressive methods, especially among ethnic minorities. Liberty, dignity, and happiness of the individual may be the cornerstones of Lockean-type nationalism, but methods used in French schools in Brittany, for example, were highly coercive. Schoolchildren caught using Breton at school were often made to wear a worn out old shoe around their necks, and the only way to get rid of it was to catch a playmate speaking Breton (Reece 1977: 31); at St. Yves School in Quimper teachers put a little ball in pupils’ mouths which passed from pupil to pupil (Reece 1977: 32). But Bretons fully conversant in French encountered no obstacles to advancement or prominence. And even unassimilated Bretons could count on equality before the law and that the law would be equitably applied to all citizens regardless of their origin.

Both the English and the French examples show that supposedly Lockean nationalisms are full of Herderian traits. Yet religious messianism and coercive incorporation do not necessarily lead to Herderianism. In fact incorporation can be quite brutal, but as long as it does not exclude citizens, it serves the purposes of inclusivity and thus Lockeanization.

In England and France we have strong, old, well-established states. But is the state framework absolutely indispensable for the formation of Lockean identity and nationalism? If we could find an example of a “stateless” ethnic entity—perhaps a province in an existing state or a federal unit—which fully conforms to the Lockean mode, we would be able to prove that Lockeanism without a state is also possible. In our opinion, we can find this kind of entity in Catalonia.

Catalan Nationalism

The Statutes of 1932 and 1979 accepted as Catalan any Spanish citizen with administrative residence in any municipality of Catalonia (Woolard 1989: 37). In the 1979 referendum on the Statute of Autonomy the key slogan during the campaign was “All those who live and work in Catalonia are Catalan” (Woolard 1989: 36). This is a quintessentially Lockean attitude based on jus soli and a political/territorial allegiance. Such an attitude was inevitable in a province where up to one-half of the population (estimates differ) is of non-Catalan origin. Catalonia simply could not afford to alienate one-half of its inhabitants and achieve autonomy. The support of immigrants to Catalonia, especially those from Andalusia and other parts of Spain’s southern regions, and their children was absolutely vital to create a politically meaningful Catalan identity. But no statute can make new members of a polity feel that they belong or share in the ethnic symbolism of their new home. Nor does it make them fully acceptable to the autochthons.

In the popular mind of both Catalonians and the immigrants four criteria determine one’s Catalanita: birthplace, descent, sentiment/behavior, and language—all Herderian parameters. This allows for highly varied, often unpredictable results. According to one survey, 55 percent of Andalusians permanently resident in Catalonia felt Catalan, but only 20 percent spoke the language (Strubell i Trueta; cited in Woolard 1989: 40). Castilian-speaking teenagers, children of immigrants, use birthplace as the main criterion. This may lead to a somewhat unusual situation where self-ascription is switched along the generational divide (“My husband and I are Andalusian, but our children are Catalan”; cited in Woolard 1989: 38).

On the other side the attitudes are no less ambiguous. Native Catalans who are culturally and linguistically Catalan do not fully accept even children of immigrants, unless they have been fully Catalanized. In common perception, a Catalan is a person who speaks Catalan like a native, particularly at home, as a first and habitual language (Woolard 1989: 39)—again a perfectly Herderian notion.

The picture is further complicated by the fact that group affiliation among immigrants and their children can be regional: Murcian, Andalusian, Aragonese, etc. Also, all Castilian-speaking immigrants, especially those of low socioeconomic status, can be called Murcians or Andalusians, a “generic” designation going back to two major waves of immigration which reached Catalonia after World Wars I and II respectively. The main division runs between Catalans and Castilians, who represent the centralized, and in the Francoist past, a highly repressive state.

Upon closer investigation, one finds that the label “Catalan” may cover a number of subdesignations: “Catalans of origin,” “old Catalans,” “Catalans of always” vs. “Catalans of immigration,” “new Catalans,” “Catalans by adoption,” “recent Catalans,” “newcomer Catalans,” and a number of others—but all Catalans nevertheless (Woolard 1989: 44). The non-Catalan also consists of a number of overlapping identities such as Spanish (i.e., neutral, non-Catalan), Castilian (i.e., centralist, repressive, and thus particularly abhorrent to nationally minded Catalans), or pseudo-regional, which covers all immigrants of low socioeconomic status. However, if the immigrant and especially his or her children learn to speak flawless Catalan and adopt Catalan mores and mentality, they are reassigned into the class of full-fledged Catalans. This, incidentally, points to the importance of language, supposedly a Herderian criterion, in the Lockean model, as does the French example. But in this case the language is a highway to full integration, unlike in the Herderian self-conceptualization (a Jew who speaks flawless German is a Jew; a Jew who speaks flawless French is almost French under “normal” circumstances).

The Catalan example shows that the official stance may not completely reflect popular attitudes. In fact there are significant Herderian elements in Catalan identity, just as there are in the English identity and nationalism. To a large extent Catalonia was forced into the Lockean mode by the political realities of a large immigrant population. However, we should not overstate the case either: under similar circumstances the Russian minorities in the more Herderian Latvia and Estonia are not accepted as full-fledged Latvians or Estonians, although citizenship will be extended if the Russians learn the local languages.

Does the Catalan example invalidate the crucial role of the state in the formation of Lockean nationalisms? We believe that it does, but only to a certain extent since Catalan identity was formed within a powerful and prosperous state which flourished in the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries and left a lasting imprint on Catalans. With the union of Aragon and Castile (in 1479) Catalonia lost its statehood (although not its parliament), but its identity, now demoted to the regional level, persists until today.

There is a long-standing and well-entrenched assumption that Lockean nationalisms are not to be found in Eastern Europe. We believe this is not the case and offer Hungary as an example of a largely Lockean mode in East-Central Europe.

Hungarian Nationalism

As in Western Europe, natio Hungarica initially included only members of the dominant class, mostly gentry, who lived within the limits of the Kingdom of Hungary. Being Hungarian thus had no ethnic connotation. All landowners, be they Magyar, German, Slovak, Romanian, Serbian, or whatever, whether they spoke Hungarian or not, were regarded as members of the Hungarian nation (Islamov 1992: 166). The State Assembly of 1764 refused a request by the Serbian Church Council for special privileges precisely because “we believe they [Hungarian Serbs] are all Hungarians” (ibid.).

Although the Hungarian language knew only one designation for the country, Magyarorszag—i.e., the land of the Magyars (Islamov 1992: 167)—historical Hungary was a political and territorial entity along Lockean lines. When, as a result of the Compromise of 1867, Hungary achieved the status of an autonomous unit within the Hapsburg Empire, less than half of its population was of Hungarian ethnic stock. It thus faced a problem similar to that of France at the end of the eighteenth century or that of Catalonia in the twentieth, although Hungary’s problem was much more severe. It is therefore hardly surprising that Hungary embarked on a policy of Magyarization, similar to France’s Francophonization seventy-five years before. Hungarian became the state language, and minority languages were gradually suppressed, despite a fairly liberal Nationalities Law of 1868 (Rusinow 1992: 252). Transylvania lost its local autonomy, and Croatia’s was severely limited. Successive governments encouraged rapid assimilation of ethnic minorities. All together, about two million non-Hungarians were Magyarized between 1850 and 1910 (Rusinow 1992: 253), an enormous figure given the Magyar population in 1853 of only 5.4 million (taken from Hain; cited in Seton-Watson 1972: 434). The reason for this success lies in the fact that any minority member could become Magyar with all the social mobility, career advancement, and advantages of citizenship as long as s/he learned Hungarian and assimilated.

Thus in its main outline Hungarian nationalism adhered to the French model. This nationalism succeeded fairly well, at least to the extent that the Magyar proportion of the total population exceeded 50 percent (51.4 percent to be precise, without Croatia) by 1900 (Hain; cited in Seton-Watson 1972: 434). That it turned away from the Lockean mode after the dismemberment of historical Hungary in 1919 merely shows that the choice of model is largely situational. The country lost huge minority populations it had tried to assimilate. Defeat and the harshness of the peace treaty led to resentment and rejection of non-Hungarians. As a result, Hungarian identity was redefined in ethno-racial terms.

So far we have demonstrated that Lockean nationalism is not confined to Western Europe but is encountered in Eastern Europe as well. We have also shown that the statist framework, although important, is not indispensable for the appearance of Lockean nationalism. An old statist identity demoted to the level of regional identity may suffice, at least in Western Europe, to produce Lockean nationalism. Thus we are left with the proposition that Lockean nationalism is largely a function of individual incorporation based on jus soli. This kind of incorporation promotes inclusivity. Moreover, it does not matter if it is promoted by coercive methods, as in France or Hungary, or is purely voluntary, as in Catalonia. Nor does the presence of occasional Herderianisms, such as messianism and a religious matrix, invalidate the Lockean character of inclusive nationalisms.

We have only one more type of nationalism to find in order to complete the matrix: a Lockean-inclusive nationalism of the nonstatist kind in Eastern Europe. We believe that Belorussian (or Belarusan, in the latest terminology) nationalism is a good example.

Belorussian Nationalism

Originally a part of the Kievan Rus’, the Belorussian lands were gradually incorporated into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Already at the end of the twelfth century some Krivichan lands (Krivichi is one of the three tribes from which the Belorussian ethny later developed) passed under Lithuanian rule (Wasilewski 1920: 264–65). By the time Lithuania captured Kiev (in 1362) virtually all Belorussian lands had become part of the Grand Duchy. The incorporation was gradual and proceeded through marriage or agreement when western Russian principalities sought Lithuanian protection against hostile neighbors (Vakar 1956: 43).

The Grand Duchy itself was Lockean: all inhabitants, whatever their ethnic stock, considered themselves Lithuanian. Lithuanian Slavs were no exception; they called themselves licviny or litoucy—i.e., Lithuanians (Zaprudnik 1993: 4). Since the Slav population of the duchy was more advanced culturally and economically, Old Russian was accepted as the language of state. Repeated intermarriage of the leading Lithuanian families with Russian princesses (sixteen toward the end of the fifteenth century; four consecutive generations of the grand dukes had Russian mothers and Russian wives [Vakar 1956: 51]) brought strong Russian influence to the Lithuanian court. The Old (Belo)russian language and culture had prestige, and gradually much of the Lithuanian upper strata were Russianized. At the time, the language of religious writings was uniform among all Eastern Slavs, but the vernacular was already beginning to diverge from other Russian dialects, largely through local developments and borrowings from Polish.

History set Belorussians apart from other Eastern Slavs. After the first union of Lithuania and Poland in 1385, the proto-Belorussian population was subjected to strong Western (largely Polish) influence. And the Reformation rendered it multiconfessional, especially among the aristocracy, with the Orthodox, Catholics, and Protestants forming part of a whole. Typically Belorussia did not know large-scale ethnic or religious strife, either during the Reformation or later. The only massacres were perpetrated by Muscovite troops, who often killed Catholics and Jews in towns they captured. Compared to most of their neighbors, Belorussians have been remarkably tolerant. Westernization was further strengthened by the organization of city life along German models (the Magdeburg law) in the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries.

As the pressure from Muscovy increased after 1550, the Lithuanian lands, including Belorussia, drew closer to Poland. For its part, the Polish crown met them half way: the anti-Catholic provisions of the Horodlo Union of 1415 were struck down (in 1562), and the country was reorganized along federal lines in 1569 (Zaprudnik 1993: 29). (The extent and degree of federalization have been hotly disputed ever since.) The retreat of the Reformation and the imposition of the Union of Brest (by which the Orthodox acknowledged papal authority and Catholic dogma in return for a compromise on the Eastern rite, services in Slavonic, and priest celibacy [Vakar 1956: 56]) put Belorussia under increasing Polish influence. Eventually this began to affect the status of the Belorussian language. The Statutes of the Grand Duchy (codes of law) in 1529, 1566, and 1588 were all written in Belorussian. It was still the language of the ducal chancellery, the courts, the chronicles, and diplomacy (Zaprudnik 1993: 37). Until the seventeenth century, when many noble families in Lithuania and Belorussia started switching to Polish, Belorussian played the same role in the Grand Duchy that Latin had played in most European countries in the Middle Ages.

With the loss of large sections of Ukraine to Muscovy in 1654, the weight of the Eastern Slav element in the Polish Commonwealth decreased while that of Poland expanded. In 1696 Polish was made the official language (Zaprudnik 1993: 39). Catholic (i.e., Polish) monasteries and religious establishments proliferated; conversion to Catholicism became an initiation into a higher form of civilization and a mark of distinction (Vakar 1956: 57). In Catholic homes first, in others later, Polish began to replace Russian, much like earlier Old Russian had replaced Lithuanian. Between 1596 (the Union of Brest) and 1795 (the Third Partition) most of the Belorussian nobility, gentry, and burghers were thoroughly Polonized (Zaprudnik 1993: 45). The process did not proceed without resistance. The Chamberlain of Smolensk called Polish culture “a dog’s flesh clothing our Russian bones” (Vakar 1956: 61) (so much for the absence of nationalist senti-ments before the eighteenth century); Orthodox fraternities were organized in towns and uprisings erupted in the countryside. In vain, Polonization continued to spread, although as late as the last decade of the eighteenth century there were still old-fashioned lords who liked to talk Belorussian among themselves (Czeczot; cited in Wasilewski 1920: 269).

The Polish partitions were justified by Russia as the in-gathering of all Rus’—i.e., regaining of the Kievan Russian patrimony. After the Second Partition a commemorative medal was minted in St. Petersburg with an inscription, “What had been torn away I returned” (Ottorzhennaia vozvratikh [Vakar 1956: 66]). Ironically the Russian governments under Paul and Alexander I were not aware of the fact that the greater part of the Belorussian Slav population were not Polish, mostly because the gentry and the other educated sections of the population with which they dealt were Polish. Catholics preserved all former privileges; local administration and education were left in Polish hands, and Polonization continued unabated. It was only after the insurrections of 1830–31 and 1863, in the context of general anti-Polish repressions, that St. Petersburg “discovered” the non-Polish character of the Belorussian peasantry. Both insurrections were widely supported in Belorussia. In 1863, for example, 18 percent of the insurgents were (non-Polish) peasants, although most insurgents—about 70 percent—originated among the heavily Polonized gentry (Zaprudnik 1993: 57). To counter Polish “subversion,” the Russian government purged Poles from local administration and banned the Polish language from schools and administration. (Ironically the use of Belorussian was also prohibited on the mistaken assumption that it was a Polish dialect [Vakar 1956: 69].) However, some leading Russian figures such as Aksakov and Katkov finally woke up to the fact that Belorussians were not Polish.

Depolonization gained momentum in 1839, when the Uniate hierarchs renounced the Union of Brest and returned to the Orthodox fold. This was the final blow to the Uniate Church: after the First Partition about 1.5 million Uniates had converted to the Orthodox faith (Vakar 1956: 68). Now the remaining 1.5 million were registered, often against their will, as Orthodox (Vakar 1956: 69). In 1840 even the names Belarus and Litva were banned; instead Belorussia became known as the Northwestern Province (Zaprudnik 1993: 50).

The insurrections precipitated a radical transformation of Belorussia. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, before the appearance of nationalism, one’

The renunciation of the Union of Brest (the Uniate denomination itself had plebeian connotations) eliminated a middle category, a no-man’s land between Orthodoxy and Catholicism, and split Belorussian Christians between Orthodox/Russian (81 percent in 1897) and Catholic/Polish camps (18.5 percent, according to Zaprudnik 1993: 63). The situation was further complicated by the fact that the vast majority of the educated and the affluent were culturally alien: as late as 1917, 97.4 percent of urban dwellers were non-Belorussian (Zaprudnik 1993: 67). In Minsk in 1897, 51.2 percent of the entire population was Jewish and 25.5 percent Russian; only 9.3 percent was Belorussian (Wasilewski 1920: 93). This is hardly surprising: the ruin of the Polish gentry after the abolition of serfdom in 1861 and the confiscations of 1863 eliminated the economic and social powers of a major Polish-leaning stratum of the population. This propelled a large section of the Jewish intelligentsia and, to a smaller extent, the business class toward Russian culture. And this introduced the Russian language into the Catholic parts of the former Grand Duchy (Wasilewski 1920: 76). Earlier, even among peasants perhaps 10 percent could read Polish while only 1 percent could read Russian (Zaprudnik 1993: 55). After 1863 Russian began to gain ground. Even Lithuanian nationalists preferred to communicate with Poles in Russian since it did not threaten the existence of the Lithuanian ethny.

By the end of the nineteenth century, when nationalism “switched” the major boundary marker from religious denomination to language, the whole structure of ascriptive categories was radically transformed. Inevitably the fluidity of linguistic and denominational boundaries led to extremes of ascriptive confusion. As Wasilewski wrote,

In Lithuania and Belorussia we have people who speak the language of one people but who ascribe themselves to another. We have Lithuanians who cannot speak a word of Lithuanian, Poles who are very much attached to the Polish people, yet who speak (i.e., whose mother tongue is) Lithuanian, Belorussian or Latvian. We have ”locals" who speak “vernacular” who define their nationality by denomination. We have families where siblings belong to two different nationalities. We have such wonders as the representative from Pinsk in the First Duma who was Polish by language and culture, came from a Lithuanian family, and considered himself Belorussian even though he grew up in Ukrainian (ethnic) territory and was closely connected with it (1920: 85).

On the other hand, such fluidity allowed the inclusion in one’s ethny of people who spoke another language and came from a different ethnic stock. This was particularly important in disputed border areas with mixed population. Here, paradoxically, acceptance and tolerance became instruments of expansion. This was particularly true in the Vilna region. Vilna had special significance for many Belorussians. Not a few still considered the city as their capital, and during the revolution of 1905 it was the first choice for convening the Belorussian Constituent Assembly (Vakar 1956: 86). The city and the vicinity were mixed in the extreme. In 1897 in the city proper 40 percent of the population was Jewish, 31 percent Polish, and 20 percent Russian. Belorussians amounted to only 4 percent and Lithuanians to barely 2 percent. In the surrounding countryside the population was even more fragmented: 26.4 percent Belorussian, 21.7 percent Jewish, 21.4 percent Lithuanian, 20.6 percent Polish, and 10.7 percent Russian (Vakar 1956: 10). The census of 1897 was conducted by Russian authorities who had an anti-Polish and anti-Jewish bias and probably listed many Belorussians as Russians. The German census of 1916 (during German occupation), which presumably was not similarly biased, found 70 percent Poles, 23.9 percent Jews, 3.5 percent Belorussians, and 2.8 percent Lithuanians (Vakar 1956: 11) (after a mass evacuation of Russians and a large-scale expulsion of Jews by the Russian authorities). Clearly the percentage of Poles in this census was greatly inflated by adding Polish-speaking Belorussians, Jews, and Lithuanians.

This trend was continued in independent Poland. As in the times of the Commonwealth, the Belorussian was considered gente Russus, natione Polonus and was called bialopolski, (White Polish). This way the total number of Belorussians in the first Polish census of 1921 was brought down from about 3.5 million (Zaprudnik 1993: 83) to 1.03 million. In other words, only Orthodox Belorussians were counted as Belorussians. Among the Roman Catholics only 60,000 registered or were allowed to register as Belorussians, the rest being added to the Polish numbers. It is interesting that in Polesie at this late date, 62.5 percent of the entire population still considered itself “local” or “undecided” (Vakar 1956: 13).

From Belorussian history, it becomes clear how Belorussian national identity managed to develop Lockean inclusivity without a statist structure. It evolved in a state based on jus soli. It belonged to the large majority of the population (as high as 80 percent in the Grand Duchy in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries). Being on a higher level of civilization, the Belorussian culture initially attracted and absorbed the upper strata of politically dominant Lithuanians. When the Belorussian-Lithuanian elites chose Polonization, the Belorussian peasantry was still nationally undecided, with religion still being the main marker of collective identity. Thus Orthodox Belorussians could be counted as Russian, while the Catholic ones could be included among Poles. By the same token, a religious conversion led to a switch in ethnic affiliation—to the extent that siblings from the same family could end up in different nationalities. Whatever their nominal nationality, they were not excluded from the Belorussian “family.” Thus the jus soli foundations of collective identity in the Grand Duchy, a long tradition of assimilation and acceptance of alien elites, confusion of denomination with ethnic affiliation, a large proportion of ethnically undecided people (the “locals”), and the desire to retain areas with mixed populations have all contributed to the creation of a nonstatist Lockean-inclusive Belorussian identity and nationalism.

In describing Lockean nationalisms, we started with classical statist models of English and French nationalisms. When we turn to Herderian nationalisms, the order should be reversed because ethnic nationalisms in Central and Eastern Europe originated and developed without the benefit of the state. In contemplating the peculiarities of Herderian nationalisms, we will start with Germany since this was Herder’s homeland and the basis for his concept of nationalism. Germany furnished the original Herderian model, which other East European nationalities were to emulate.

German Nationalism

It is often stated that until 1806 Germany knew no unified state. Strictly speaking, this is not true since the Holy Roman Empire provided the framework for pan-German unity. However, the empire was fragmented into about three hundred states and statelets which pursued their own interests, often at loggerheads with each other. But disunity did not prevent the emergence of broad cultural movements which developed across the whole of German cultural space. German nationalism was one of these movements. Its rise is inextricably linked with Romanticism.

Like their Western counterparts, German Romantics started as extreme individualists. But unlike the Western Romantics, Germans ended as collectivists. The transformation resulted from their longing for a true harmonious community, much like Rousseau’s. But where the Swiss philosopher sought an integrated political community, German Romantics dreamed of an organic folk community. They looked back to the imagined glories of the past, the days of order and security, the happy time when the Holy Roman Empire was the most powerful entity in Europe. German Romantics did not want French universalism and Weltburgertum; rather they hoped for a new Germany of valiant, truthful, pure, courageous men, a clear proof of Teutonic superiority, which the sense of cultural inferiority demanded in compensation. German Romantic nationalism was anti-French, anti-aristocratic, anti-cosmopolitan, anti-effete, anti-intellectual. As such, it appealed to virtually all social strata (Snyder 1976: 89).

The German version formulated by Herder and then elaborated by Johann Fichte, Johann Schlegel, Ernst Arndt, Friedrich Jahn, and Christoph Müller was an “organic” version. It postulated that the nation, unique, natural, and objective, was the true subject of history, propelled by the self-moving national spirit as it gradually unfolded through history. This idea emanated from the writings of Immanuel Kant. The organic vision was based on several premises: (1) cultural diversity of humankind (Herder’s idea); (2) national self-realization achievable only through political struggle (introduced by Fichte); and (3) the subordination and dissolution of an individual and his will in the will of the organic state (also elaborated by Fichte) (Smith 1971: 17).

From there German nationalism developed a philosophy built on (a) collective self-determination for each people; (b) a free expression of national character and individuality; and (c) a “vertical” (i.e., nonhierarchical) division of the world into equal nations, each living according to the dictates of its genius (Smith 1971: 23). When applied to an individual, it meant that s/he could not change his/her nationality at will, as is possible when it is based on political citizenship. Rudolf Hess formulates the Herderian concept of nationality with clarity and precision:

The German cannot and may not choose whether or not he will be German, but that he was sent into this world by God as a German. . . . The German everywhere is German—whether he lives in the Reich, or in Japan or in France or in China or anywhere else in the world (cited in Kamenka, ed. 1977: 11).

But the laws governing the acquisition of German citizenship were formulated long before Hess and the rise of Nazism. They derive from the Reichs- and Staatsburgergesetz of 23 July 1913, which specify that citizenship is passed by descent from parent to child, another consequence of Herder’s organic vision of ethnos (Klusmeyer 1993: 84). Thus the acquisition of German citizenship is based on jus sanguinis; in theory it excludes anyone who is biologically non-German. In that sense German, and by implication all Herderian nationalisms, are highly exclusive.

As for the role of the state, the German situation was somewhat different from that of most Central and East European ethnies since the German nation was not politically or culturally oppressed by alien masters. Furthermore, precisely because it was fragmented into numerous states, it had a multiple political expression denied to virtually every other ethny in the area. Its task therefore was unification, not a creation of state ex nihilo. The situation was quite different for “ahistorical” ethnies like Slovaks, who had virtually no upper or even middle classes to guide them through the process of national(istic) (re)birth.

Slovak Nationalism

Like most Herderian nationalisms which appeared among “ahistorical” people, the Slovak version developed in several stages. First, as far back as the seventeenth century, Jesuits began printing books in Slovak vernacular, in an effort to wean Protestants from the heretical faith (Brock 1976: 5). However, it was not until the 1780s that a group of Catholic intellectuals began to write in the vernacular, while a Catholic priest wrote a Slovak grammar and a dictionary. The net effect was a separation from the closely related Czech language and, therefore, community. This was the first step toward the delimitation of the Slovak ethnos. However, these proto-nationalists did not dispute that the Slovak gentry belonged to natio Hungarica. As Brock put it, “The feeling of separate ethnic identity is not . . . the same as consciousness of separate national identity” (1976: 7). Or in the words of Matej Bel, a Slovak intellectual of that time, an educated Slovak was someone who was “lingua Slavus, natione Hungarus, eruditione Germanus” (Brock 1976: 15–16).

In the second stage, members of the Protestant (and pro-Czech) intelligentsia influenced by German linguistic nationalism began to assert Slovak cultural and linguistic separateness, but still within the political framework of the Hungarian state. The leader of this circle, Jan Kollár, was profoundly influenced by Herder; it was from his studies at the University of Jena that he brought notions of cultural and linguistic nationalism (Brock 1976: 21). It is interesting that Kollár started as a pan-Slavist and regarded his people as members of a Slav nation. In this, he totally divorced nation and state, leaving language as the main determinant of nationality. Potentially his teaching could be used to advocate pan-Slavic unity, much like the idea of German unity was beginning to take hold across the German cultural continuum.

It was these early proto-Czechoslovak nationalists who extricated the Slovak ethnos from natio Hungarica because in their view only a common language created a nation (Brock 1976: 36). Then in the mid-1840s another group of Protestants, led by Stur, rejected the “Czechophiles” and advocated a Slovak language and nationality. This was probably a reaction to the introduction of Magyar as the national language in 1844 (Brock 1976: 39) (it replaced Latin) and the rise of Magyar assimilationist pressures, although theoretically they should have sought salvation in a closer cooperation with Czechs. Like Herder and Glazunov, Stur was an adherent of ethnic polycentrism. He even coined a special term for it, kmenovitost’ (Brock 1976: 48), from kmen’, tribe, by which he meant the (praiseworthy) ability of the Slav nation to subdivide into tribes, of which Slovaks were one.

With their Romanian and Serbian counterparts, early Slovak nationalists used language to separate (or save) the Slovak ethnos from Magyarization. They helped explode the unity of the historic Hungarian state and then preserved Slovak distinctiveness in another, less oppressive, but potentially even more dangerous union with the Czechs. From the struggle against Magyarization, the Slovak path led to the incorporation into Czechoslovakia as a nominal state nation (already in 1837 Slovaks, Czechs, and Moravians were grouped together under the heading “Czechoslovak section” in Safarik’s work on Slav antiquities [Brock 1976: 27]), nominal independence under Hitler, federal status in 1968, and finally full independence on 1 January 1993. With some modifications this was the path taken by other Herderian nationalisms.

So far we have been dealing with classically Herderian, nonstatist nationalisms of Central and Eastern Europe. If we could find a statist Herderian nationalism in the same area, we would have one more example, from the other side of the Lockean/Herderian divide, that the state’s involvement, framework, and structure are important determinants of the type of nationalism. To explore this possibility let us turn to Russia/the Soviet Union.

Russian Nationalism

From its beginnings in the eighteenth century the Russian national idea defined the nation as (1) a collective individual (2) formed by ethnic, primordial factors such as blood, soil, and language, and (3) characterized by the enigmatic soul or spirit (Greenfeld 1992: 261). In this, Russian national identity, as conceptualized by the Russian elite, was no different from its German, Slovak, or other Herderian counterparts, although the importance attached to a specific component might have differed from nationalism to nationalism and from epoch to epoch. As in many other aspects, the former Soviet Union retained and continued, through all the ideological permutations, the Russian national idea.

The USSR was unique among (semi)-European countries in that it had an official ethnic nationality inscribed in one’s internal passport, along with citizenship, which was of course Soviet. At age 16, when the Soviet citizen acquired an internal passport, s/he had to choose his/her nationality. S/he had no choice if both parents were of the same nationality but could choose either parent’s nationality if they came from different ethnic backgrounds. Thus a person of full Armenian ancestry was a Soviet citizen of Armenian nationality. If one of his/her parents was Russian, s/he could choose to become Russian. In practice it often led to an absurd, in Herderian terms, situation, where “real” nationality did not correspond to the official one inscribed in the passport. For example, an Armenian with a Russian grandmother could be officially Russian if his/her Russian/Armenian parent chose the Russian nationality. In large cities or any multiethnic areas one could often encounter people whose official ethnic nationality was inherited from one grandparent, or even a great-grandparent, rather than the immediate parent. Occasionally different siblings within the same family of mixed ethnic origin chose different nationalities so that a brother could be Russian while his sister chose to be Armenian (a reminder of the Belorussian situation, but there the context was entirely different).

The official recognition of ethnic nationality and a division of ethnic and state nationality puts the Soviet Union at the extreme end of Herderian nationalisms. Presumably Russian nationalism should be classified accordingly. And yet there are some features which militate against it. First, as Milovan Djilas noted, “Muscovy (the state) came first—the Russian sense of nationhood came later” (cited in Diuk and Karatnycky 1990: 195). The precedence of statehood points to the Lockean model.

Another Lockean trend, the tendency toward ethnicization, known in Russia as Russification, has also been present throughout recent Russian and Soviet history. Already in 1870, the minister of education, Dmitriy Tolstoy, wrote that “the final objective of education to be provided . . . to the non-natives . . . is undoubtedly their Russification” (cited in Carrère d’Encausse 1992: 6). But then a similar situation existed in France, Germany (in regard to Posen Poles), and Hungary—in fact in any multiethnic state with large ethnic minorities.

What rendered Russian and later Soviet nationalisms decidedly Herderian was their nonacceptance, officially and on the popular level, of non-Russians. Before 1919, a non-Hungarian who adopted the Hungarian language and culture was accepted as Hungarian. A non-Russian who adopted the Russian language and mentality remained, according to his internal passport, non-Russian. This, we think, goes a long way toward explaining the rigidity and enmity in interethnic relations in the Soviet Union. The whole elaborate federal structure of the former Soviet Union was Herderian in character. It (a) gave collective self-determination to each people, (b) offered an institutionalized expression of ethnic character and individuality, and (c) allowed vertical (i.e., nonhierarchical) form to an intrinsically hierarchical relationship between various ethnies within the empire.

The sources of Russian Herderianism should be sought in the religious foundations of Russian identity. “The Russian people in their spiritual makeup are an Eastern people,” wrote Nikolai Berdyaev (1960: 7). Its culture was “the culture of the Christianized Tartar Empire. . . . (Its) soul was molded by the Orthodox Church—it was shaped in a purely religious mold” (1960: 8). This is hardly surprising. Russia for several centuries was the only independent Orthodox polity on earth. It had a mission, a messianic vocation, to lead the Orthodox people and to protect the faith. One could not be Russian and non-Orthodox, any more than one could be Soviet and anti-Communist. Moscow the Third Rome was replaced by Moscow the Capital of the World Proletariat. Forms changed; messianism remained.

But, as mentioned above, religion molded the earliest French identity, and messianism was no less pronounced in the Lockean English nationalism. Perhaps we should seek the explanation in the Russian emphasis on commonality—i.e., communal spirit (sobornost’) or, in Leo Tolstoy’s word, roievost’ (beehiveness). In practice these concepts implied that the individual’s will had to be absorbed or lost in that of the community, the village mir, which was later enlarged and redefined as a religious community of the organic state. That is, incidentally, a major factor in making the Russian people receptive to totalitarian ideologies of all stripes. From the village commune and on to the Communist collective, a Russian and a Soviet person was supposed to be a member of the community. Such community could be easily redefined in völkisch terms, as the national community, the collective of collectives. Endowed with a sense of mission, such a community could easily develop an intolerant and highly ideological Herderian nationalism.

It is no accident that the controversy about the Russian mission molded the emerging Russian nationalism. The question of national mission was raised by Schelling and Hegel, who asked what each major country had contributed to the advance of civilization. Compared to the West, at least until the early nineteenth century, Russia had contributed very little; hence the feelings of cultural inferiority which marked Russian (indeed all) Herderian nationalisms. The controversy which ensued split the Russian intelligentsia into two camps—the Slavophiles, some of whom later drifted into ethnic exclusivity and rabid nationalism (often with a pan-Slavic bend), and the Westernizers, who looked toward Europe.

The West, according to Slavophiles, was poisoned with rationalism. Russia drew its strength from sobornost’. In the West the foundations of organized life were individualistic and legalistic. Russians, thanks to Orthodoxy, managed to retain “integral” personalities. A Westerner is “alienated.” In Russia every individual is submerged in the community (Pipes 1974: 267). Slavophiles were “organicists”—i.e., they admired organic development, which, ironically, made them profess great admiration for what they believed was the English organic development, as opposed to the “artificial” French and German varieties.

Narodnost’, national outlook, was introduced as early as 1832, virtually simultaneously with the appearance of Slavophilism, by the minister of education, Count Uvarov, who enunciated the “truly” Russian . . . principles of Autocracy, Orthodoxy and “Narodnost’” (Seton-Watson in Conquest, ed. 1986: 20). But both Nicolas I and Alexander II resisted narodnost’ because of its populist implications. Only under Alexander III, under the onslaught of recently imported socialism, did nationalism finally get the stamp of official approval. However, Russian nationalism of the time was intermingled with imperialism, and here Russian was on a par with other imperial nationalisms—English, French, even American. The trend continued in the Soviet Union. And although individual non-Russians did achieve the highest levels of power—Stalin, for example—the party apparatus and the army remained predominantly an ethnic Russian preserve, with a minor addition of other Eastern Slavs.

Nothing betrays the Herderian character of Russian nationalism better than the campaign against bezrodnyie kosmopolity, “footloose cosmopolitans,” in the late 1940s and early 1950s. It was directed mostly against Jews, who—in the eyes of the nationalists—stood for everything negative, unnatural, un-Russian: rootless, international in outlook, pro-Western. At the same time, in a bizarre twist of Orwellian doublespeak, the concept of “internationalism” came to imply, in certain contexts, the willingness of non-Russians to live with the Russian Big Brother (in “fraternal agreement”), eventually leading to voluntary Russification.

As one surveys the last three centuries of Russian and Soviet history, one is struck by the multiplicity of Russian nationalisms: the Slavophile nationalism based on Orthodoxy, the “racial” chauvinism of the Black Hundreds, the official Soviet and unofficial Russian Soviet nationalisms. But they all extolled the organic commonality, the link with the sacred Russian soil, and the power and expanse of the enigmatic Russian soul, which puny, rational, individualistic Westerners cannot hope to fathom. And virtually all varieties of Russian nationalism were—and still are—heavily anti-Semitic. From the Black Hundreds of the 1880s to Pamiat’ of our time, the Jew has always been the symbol of everything un-Russian: urban, mobile, skeptical, international in outlook, and ultimately dangerous.

To summarize: Russian nationalism is an extremely complex phenomenon. Although Herderian, it displays discernible Lockean tendencies due mainly to the precedence of Russian statehood. Its Lockean side has been obscured because of the large-scale (mis)appropriation of German nationalist vocabulary in the first half of the nineteenth century, the Herderian excesses of the Slavophile wing, and the relunctance of successive tsarist governments to utilize nationalist concepts because of their populist (and implicitly democratic) overtones. (When the government finally did, in an attempt to stop the spread of socialism, it was too late.) Still, despite the presence of strong Lockean traits, virtually all types of Russian and Soviet nationalism are thoroughly Herderian, much as English nationalism and identity remain Lockean despite numerous Herderian features. So far we have been able to find both statist and nonstatist Herderian nationalisms in Eastern Europe. We must now try to do the same in Western Europe. Of the nonstatist variety there are several: Flemish, Ulster-Protestant, Breton. We will take Basque, in close proximity to nonstatist Lockean Catalan nationalism, and two rigid statist Lockean ones, French and Spanish, to illustrate our point.

Basque Nationalism

Like their East European counterparts, Basques base their identity on language and culture (Payne 1975: 9). To be Basque, one has to have been born in the Basque country, speak Euskera, have at least four Basque surnames to indicate four Basque grandparents—i.e., purity of descent—and come from the countryside, which is supposed to be “purely” Basque (M. Heilberg in Grillo 1980: 46).

Basque history starts with resistance to Muslim invaders. Along with Asturia, the Basque country was the only part of Iberia which had successfully resisted the conquest. Although the Basques had never formed a unified polity, Basque identity was forged in constant warfare against the other religion, Islam.

The incorporation of various Basque principalities into the Spanish state was a gradual process and did not generate a “nationalistic” Basque-against-Castilian type of reaction. Until the eighteenth century Basque society remained the most traditionalist on the peninsula, in contrast to Catalonia, which had been the most advanced region since as early as the thirteenth century. Economic development, which started in the late eighteenth century, transformed the Basque country into another most advanced area of the kingdom. Yet socially it remained the most Catholic and conservative.