|

|

|

|

Final Report With Executive Summary

Carnegie Corporation of New York

1997

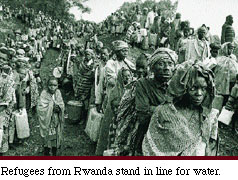

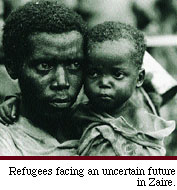

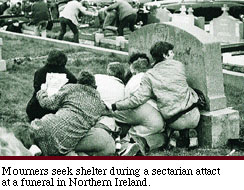

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, over four million people have been killed in violent conflicts. In January 1997, there were over 35 million refugees and internally displaced persons around the world. 1 The violence that generated this trauma has been in some cases chronic. In others, there have been tremendous spasms of destruction. For example, the 1990s have witnessed protracted violent confrontation in Bosnia and Chechnya and a massive genocide in Rwanda. The circumstances that led to the 1994 Rwandan genocide provide an extraordinary and tragic example of the failure of the world community to take effective preventive action in a deadly situation. With well over one-half million people killed in three months, this has been one of the most horrifying chapters in human history. 2

Hopes for a better and saner world raised by the end of the Cold War have largely evaporated. Despite a massive and protracted effort toward global nuclear disarmament, no comprehensive approach to preventing a nuclear catastrophe has been articulated by governments, much less put in place. Although the nightmare of deliberate nuclear war has, for the time being, been dispelled, the risk of deliberate use of nuclear weapons by terrorists remains very much with us. Because of the degrading of stockpile controls, the danger of inadvertent use of nuclear weapons is now greater than it was during the Cold War.

Hopes for a better and saner world raised by the end of the Cold War have largely evaporated. Despite a massive and protracted effort toward global nuclear disarmament, no comprehensive approach to preventing a nuclear catastrophe has been articulated by governments, much less put in place. Although the nightmare of deliberate nuclear war has, for the time being, been dispelled, the risk of deliberate use of nuclear weapons by terrorists remains very much with us. Because of the degrading of stockpile controls, the danger of inadvertent use of nuclear weapons is now greater than it was during the Cold War.

Violent conflict continues at an alarming level, albeit now nearly exclusively within states. As a result, both policymakers and scholars have sought to go beyond the traditional ideas of containing and resolving conflict. While governments are understandably reluctant to become involved, either singly or collectively, in distant disputes that are both bloody and seemingly intractable, they recognize that they may nevertheless become embroiled in the widespread repercussions of these disputes. Therefore, a strong common interest has grown in recent years to find better ways to prevent violent conflict, with the immediate goal of identifying relatively modest measures which, if taken in time, could save thousands of lives.

Violent conflict can be traced to historical events, long-held grievances, economic hardship, attitudes of pride and honor, grand formulations of national interest, and related decisions by leaders or groups inclined to pursue their objectives by violence. Struggle, domination, and conflict have been recurrent features of human history, but mass violence with modern weapons does not, and thus should not, have to be a fact of life. Deadly conflict is not inevitable. The Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict does not believe in the unavoidable clash of civilizations or in an inevitably violent future. War or mass violence usually results from initial deliberate political calculations and decisions. This observation is perhaps the most significant lesson of the events in Rwanda in 1994.

At this writing, the 1994 slaughter in Rwanda still reverberates in that country, in the region, and in capitals around the world. For the international community, the chief legacy of Rwanda is the knowledge that mass violence rarely happens without warning and that the absence of external constraints allows genocide to occur. Article II of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide (1948) defines genocide as

| Many of the following acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: (a) Killing members of the group; (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; [and] (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. |

The history of politically motivated animosity between Hutu and Tutsi in Rwanda dating back to colonial rule was widely known. A dramatically new situation was created when the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), supported by Uganda, invaded Rwanda in October 1990. The human rights group Africa Watch warned in 1993 that Hutu extremist leaders had compiled lists of individuals to be targeted for retribution—individuals who the next year were among the first victims. 3 The implication of the RPF invasion and intensified warnings of a genocidal plot, received months before the plane crash that killed President Habyarimana of Rwanda and President Ntaryamira of Burundi, went unheeded by countries and international organizations in a position to thwart the plot. When the plane crash triggered the genocide, the reaction of the United Nations Security Council was to distance itself from the situation. The Security Council voted to withdraw all but 250 of the 2,500 troops of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), which had been authorized a year earlier by the Council to play a traditional peacekeeping role in support of the stillborn peace process. UNAMIR's mandate was so narrowly drawn and the force remaining in place so small that it could not intervene to halt the genocide.

It took four months for the UN to reverse itself and decide to send 5,000 peacekeeping troops to Rwanda with a mandate to protect civilians at risk and to provide security for humanitarian assistance.  But member states took no concrete steps to act on their decision—no new UNAMIR troops were forthcoming—in part because troop-contributing countries had fresh memories of the bitter experience in Somalia. Meanwhile, perhaps 800,000 Rwandans had been slaughtered before an invading force of Tutsi-led exiles from neighboring Uganda routed the perpetrators of the genocide and sent two million Hutus fleeing into Zaire, Tanzania, and Burundi. Interspersed among the refugees were armed Hutu militia who had committed the genocide. They took control of the refugee camps, stole supplies intended for humanitarian relief, and embarked on an insurgency against the new government in Rwanda.

4

UN appeals for assistance to prevent further conflict went

unheeded, and the violence spread and escalated, particularly in eastern Zaire. When Rwanda and other neighboring countries sent military forces into eastern Zaire, they set in motion an insurrection that eventually toppled the government of dictator Mobutu Sese Seko. We now know that while the world watched the dramatic march across Zaire of the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (ADFL), thousands of Hutu refugees were being systematically hunted down and slaughtered. These events only extended the cycle of deadly conflict within the region.

5

But member states took no concrete steps to act on their decision—no new UNAMIR troops were forthcoming—in part because troop-contributing countries had fresh memories of the bitter experience in Somalia. Meanwhile, perhaps 800,000 Rwandans had been slaughtered before an invading force of Tutsi-led exiles from neighboring Uganda routed the perpetrators of the genocide and sent two million Hutus fleeing into Zaire, Tanzania, and Burundi. Interspersed among the refugees were armed Hutu militia who had committed the genocide. They took control of the refugee camps, stole supplies intended for humanitarian relief, and embarked on an insurgency against the new government in Rwanda.

4

UN appeals for assistance to prevent further conflict went

unheeded, and the violence spread and escalated, particularly in eastern Zaire. When Rwanda and other neighboring countries sent military forces into eastern Zaire, they set in motion an insurrection that eventually toppled the government of dictator Mobutu Sese Seko. We now know that while the world watched the dramatic march across Zaire of the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (ADFL), thousands of Hutu refugees were being systematically hunted down and slaughtered. These events only extended the cycle of deadly conflict within the region.

5

Since 1994, many knowledgeable people, including the commander of UNAMIR at the time, have maintained that even a small trained force, rapidly deployed at the outset, could have largely prevented the Rwandan genocide. 6 But neither such a force nor the will to deploy it existed at the time (see Box P.1). The Organization of African Unity (OAU) was incapable of such a preventive action, and no North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member was prepared to take such a step as part of a NATO intervention or on its own. When concerned governments finally turned to the United Nations and to the Security Council, there was neither a credible rapid reaction force ready to deploy nor the moral authority or will to assemble one quickly enough. The situation was not helped by the fact that France and the United Kingdom were heavily involved militarily on the ground in the UN force in Bosnia; in the case of the United States, the political legacy of Somalia still seemed to haunt decision makers.

|

International relief and reconstruction efforts over the three years following the slaughter cost the international community more than $2 billion. Yet, according to one study, the estimated costs of a preventive intervention would have been one-third of this amount and would have very likely resulted in many thousands fewer casualties. 7

The Rwandan tragedy is the kind of situation that is likely to recur when a great human disaster looms in a region of little strategic or economic concern to the major powers who currently constitute the crucial permanent membership of the Security Council. To help prevent such mass violence, the Commission is convinced that reform of the Security Council to strengthen its legitimacy and efficacy in prevention is urgent. The Commission believes that Security Council membership needs to be expanded to reflect more accurately the distribution of power in the regions of the world of the twenty-first century (see pages 140-143). In the Commission's view, an expanded Security Council will be better able to finance and sustain measures necessary to prevent deadly conflict, including a Security Council rapid reaction capability. 8

The Commission also believes that as part of that capability, a rapid reaction force is needed, the core of which should be contributed by sitting members of the Security Council. 9 The nucleus of such a force would be composed of a well-trained, cohesive infantry brigade with its own organic weapons, helicopters for in-country transportation, and compatible logistical and communication support. It would need the ability to react rapidly in potentially violent intrastate situations or in certain types of interstate crises but would not be a substitute for the normal range of UN peacekeeping operations. A more detailed discussion of this issue and recommendations that bear directly on the international community's ability to respond to circumstances of imminent mass violence can be found on pages 65-67.

The Commission recognizes that its commitment to the possibilities and value of preventive action is not universally shared. Skeptics argue that preventing the outbreak of mass violence will often be difficult, costly, and hazardous—perhaps even futile. Preventive measures must be applied in time in order to be effective, but no one can predict in advance the point at which a crisis will take an irreversible turn for the worse. On the receiving end, countries closest to the conflict may not want preventive assistance at a stage when it could be most effective. Countries involved in intrastate disputes often oppose the intervention of other states because they distrust their intentions or fear the consequences of intervention. Many countries resent intrusion into what are viewed as domestic affairs—maintaining law and order is still universally regarded as essentially a domestic problem. Countries often invoke the principle of national sovereignty as a barrier to early engagement, an issue this report takes up in greater detail in chapter 6.

For their part, the governments of states most capable of offering assistance—the wealthy industrialized countries—often perceive little or no national interest in engaging in some conflicts. There often may be no immediate imperative or strong interest for major states to act, aside from a strong humanitarian impulse. There is also a danger that frequent response can lead to "intervention fatigue."

The members of the Commission do not share the pessimism that underlies these views. While preventive efforts are certainly difficult, they are by no means impossible. They have been effective in a number of cases discussed throughout this report. Many preventive efforts are not well-known because they were undertaken quietly. As UN Secretary-General U Thant said of the preventive negotiations over the future of Bahrain in the late

1960s, the perfect preventive operation "is one which is not heard of until it is successfully concluded, or even never heard of at all."

10

And indeed, intervention fatigue is itself an argument for more effective preventive action. Such action should be taken as early as practicable: the earlier the steps to avert a crisis, the lower the costs of engaging.

The members of the Commission do not share the pessimism that underlies these views. While preventive efforts are certainly difficult, they are by no means impossible. They have been effective in a number of cases discussed throughout this report. Many preventive efforts are not well-known because they were undertaken quietly. As UN Secretary-General U Thant said of the preventive negotiations over the future of Bahrain in the late

1960s, the perfect preventive operation "is one which is not heard of until it is successfully concluded, or even never heard of at all."

10

And indeed, intervention fatigue is itself an argument for more effective preventive action. Such action should be taken as early as practicable: the earlier the steps to avert a crisis, the lower the costs of engaging.

For every violent conflict under way today, there are many more disputes between deeply divided peoples and in deeply divided societies that have not escalated to warfare. This study is an attempt, in part, to understand why. In any event, the lack of an explicit, systematic, sustained focus on the prevention of deadly conflict means in practice that a preventive approach as recommended by the Commission has scarcely been tried.

Toward a New Commitment to Prevention

Preventive action to forestall violent conflict can be compared to the pursuit of public health. Thirty years ago, we did not know precisely how lung cancer or cardiovascular disease developed or how certain behavior, such as smoking or high-fat, high-cholesterol diets, increased the likelihood of contracting these diseases. With the advances in medicine and preventive health care over the past three decades, we have more accurate warning signs of serious illness, and we no longer wait for signs of such illness before taking preventive measures. So too in the effort to prevent deadly conflict, we do not yet completely understand the interrelationship of the various factors underlying mass violence. We know enough, however, about the factors involved to prescribe and take early action that could be effective in preventing many disputes from reaching the stage of deadly conflict.

This report points the way to a worldwide coordination of efforts toward this goal. This effort is, of course, only a beginning. By initiating discussions throughout the world and through a variety of publications, the Commission hopes to stimulate thinking and action on the prevention of deadly conflict. Our aim is to lift the task of prevention high on the world's agenda and to encourage the investment of both public and private resources in this vital endeavor. The Commission believes that all governments and peoples have a stake in helping to prevent deadly conflict, and that it is possible—indeed essential—to develop, in the light of experience, better and more effective approaches to this problem.

Conflict, war, and needless human suffering are as old as human history. In our time, however, the advanced technology of destruction, the misuse of our new and fabulous capacity to communicate, and the pressure of rapid population growth have added monstrous and unacceptable dimensions to the old horrors of human conflict. We must make a quantum leap in our ability and determination to prevent its deadliest forms because they are likely to become much more dangerous in the next several decades.

Preventing the world's deadly conflicts will be a highly complex undertaking requiring a concerted effort by a wide range of parties. Prevention will never be an easy, instinctive, or costfree cure for the global blight of mass violence. Preventing such violence requires early and concerted reaction to signs of trouble, and deliberate operational steps to stop the emergence and escalation of violence. Prevention will also require long-term policies that could reduce the likelihood of conflict by encouraging democratization, economic reform, and cross-cultural understanding. Prevention entails action, action entails costs, and costs demand trade-offs. The costs of prevention, however, are minuscule when compared with the costs of deadly conflict and the rebuilding and psychological healing in its aftermath. This report seeks to demonstrate the need for a new commitment—by governments, international organizations, opinion leaders, the private sector, and an informed public—to help prevent deadly conflict and to marshal the considerable potential that already exists for doing so.

Notes

Note 1: Berto Jongman, "War and Political Violence," in Jaarboek Vrede en Veilegheid 1996 (Yearbook Peace and Security) (Nijmegen: Dutch Peace Research Center, 1996), p. 148. See also European Conference on Conflict Prevention, From Early Warning to Early Action, A Report on the European Conference on Conflict Prevention (Amsterdam: European Conference on Conflict Prevention, 1996), pp. 11, 15; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and International Peace Academy, Healing the Wounds: Refugees, Reconstruction, and Reconciliation, Report of the Second Conference Sponsored Jointly by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the International Peace Academy, June 30-July 1, 1996, p. 1. See also, Francis M. Deng, Protecting the Dispossessed: A Challenge for the International Community (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 1993), p. v. Back.

Note 2: See U.S. Committee for Refugees, World Refugee Survey 1997 (Washington, DC: Immigration and Refugee Services of America, 1997), p. 84. Back.

Note 3: Federation Internationale des Droits de l'Homme, Africa Watch, Union Interafricaine des Droits de l'Homme et des Peuples, Centre International des Droits de la Personne et du Developpement Democratique, Rapport de la Commission Internationale d'Enquete sur les Violations des Droits de l'Homme au Rwanda Depuis le 1er October 1990 (New York: Africa Watch, 1993), pp. 62-66; Charles Trueheart, "U.N. Alerted to Plans for Rwanda Bloodbath," Washington Post, September 25, 1997, p. A1. Back.

Note 4: See, for example: Humanitarian Aid and Effects, The International Response to Conflict and Genocide: Lessons from the Rwanda Experience, Study 3 (Copenhagen: Steering Committee on the Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda, 1996), p. 52; Barbara Crossette, "Agencies Say U.N. Ignored Pleas on Hutu," New York Times, May 28, 1997, p. A3; "Open Wounds in Rwanda," New York Times, April 25, 1995, p. A22; John Pomfret, "Aid Dilemma: Keeping It from Oppressor," Washington Post, September 23, 1997, p. A1. Back.

Note 5: Eleanor Bedford, "Site Visit to Eastern Congo/Zaire: Analysis of Humanitarian and Political Issues," USCR Site Visit Notes (Washington, DC: U.S. Committee for Refugees, 1997), pp. 4-7. Back.

Note 6: The question of whether a rapidly deployed UN force could have dramatically reduced the level of violence in Rwanda was the focus of a conference, "Rwanda Retrospective," cosponsored by the Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict, the Institute for the Study of Diplomacy, Georgetown University, and the U.S. Army, January 23, 1997. For a brief review of the conference, see Scott R. Feil, "Could 5,000 Peacekeepers Have Saved 500,000 Rwandans?: Early Intervention Reconsidered," ISD Reports III, No. 2, Institute for the Study of Diplomacy, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, April 1997. See also the full conference report, Scott R. Feil, Rwanda Retrospective, Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict, Washington, DC, forthcoming. Former UNAMIR commander Major General Romeo Dallaire asserted, "I came to the United Nations from commanding a mechanized brigade group of 5,000 soldiers. If I had had that brigade group in Rwanda, there would be hundreds of thousands of lives spared today." See "Rwanda: U.N. Commander Says More Troops May Have Saved Lives," Inter Press Service, September 7, 1994. Others have also made this point. See Brian Urquhart, "For a UN Volunteer Military Force," New York Review of Books, June 10, 1993. Back.

Note 7: The costs of relief and reconstruction are drawn from, Rebuilding Post-War Rwanda, The International Response to Conflict and Genocide: Lessons from the Rwanda Experience, Study 4 (Copenhagen: Steering Committee of the Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda, March 1996), p. 32. Costs of prevention are estimated in Michael E. Brown and Richard N. Rosecrance, eds., The Cost-Effectiveness of Conflict Prevention (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, forthcoming). Back.

Note 8: The Commission's view is spelled out in chapter 6. Commission member Sahabzada Yaqub-Khan dissents from the Commission's view on Security Council reform. In his opinion, the addition of permanent members would multiply, not diminish, the anomalies inherent in the structure of the Security Council. While the concept of regional rotation for additional permanent seats offers prospects of a compromise, it would be essential to have agreed global and regional criteria for rotation. In the absence of an international consensus on expansion in the permanent category, the expansion should be confined to nonpermanent members only. Back.

Note 9: The rotating members of the Security Council would retain their contribution for at least one year after their period on the Council so as to cover political commitments entered into while a member. Back.

Note 10: Brian Urquhart, Ralph Bunche: An American Life (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1993), pp. 427-429, 474. The dispute over Bahrain's future—then a British protectorate—became increasingly virulent in the late 1960s, threatening the delicate peace in the region. In 1969, British and Iranian officials asked United Nations Secretary-General U Thant for UN mediation to determine a mechanism to resolve the issue of Bahrain's sovereignty in accordance with Bahraini views. Representing the UN's good offices, Ralph Bunche engaged the parties in discreet and unpublicized negotiations that enabled the sensitive talks to progress. In 1970, their agreement on Bahrain's independence was approved by the UN Security Council. For further information on the Bahraini negotiations or Ralph Bunche, see Brian Urquhart, "The Higher Education of Ralph Bunche," in Journal of Black Higher Education (Summer 1994), pp. 78-85. See also Husain al-Baharna, "The Fact-Finding Mission of the United Nations Secretary-General and the Settlement of the Bahrain-Iran Dispute, May 1970," International and Comparative Law Quarterly 22 (1973), pp. 541-553. Back.