|

|

|

|

Final Report With Executive Summary

Carnegie Corporation of New York

1997

7. Toward A Culture Of Prevention

This report emphasizes that any successful regime of conflict prevention must be multifaceted and designed for the long term. To deal with imminent violence, we need better warning and more ways of responding with preventive diplomacy, sanctions, inducements, or the use of force. To deal with the root causes of violence, we need structural approaches that ensure security, well-being, and justice for the almost six billion people on the planet. Civil society in its broadest sense—including nongovernmental organizations, religious leaders and institutions, the educational and scientific communities, the media, and the business community—must play an important role in the regime. The United Nations and regional organizations are essential for marshaling the resources of the international community.

The urgency of the task should be clear. This report describes the many forces that are pushing groups into conflict: for example, irresponsible leaders, historic intergroup tensions, population growth, increasing crowding in cities, economic deterioration, environmental degradation, repressive or discriminating policies, corrupt or incompetent governance, and technological development that increases the gap between rich and poor. In the vast majority of cases, however, these forces need not lead inevitably to violence.

The urgency of the task should be clear. This report describes the many forces that are pushing groups into conflict: for example, irresponsible leaders, historic intergroup tensions, population growth, increasing crowding in cities, economic deterioration, environmental degradation, repressive or discriminating policies, corrupt or incompetent governance, and technological development that increases the gap between rich and poor. In the vast majority of cases, however, these forces need not lead inevitably to violence.

The inescapable fact is that the decision to use violence is made by leaders to incite susceptible groups. The Commission believes that leaders and groups can be influenced to avoid violence. Leaders can be persuaded or coerced to use peaceful measures of conflict resolution, and structural approaches can reduce the susceptibility of groups to arguments for violence.

Beyond persuasion and coercion, however, we must begin to create a culture of prevention. Taught in secular and religious schools, emphasized by the media, pursued vigorously by the UN and other international organizations, the prevention of deadly conflict must become a commonplace of daily life and part of a global cultural heritage passed down from generation to generation. Leaders must exemplify the culture of prevention. The vision, courage, and skills to prevent deadly conflict—and the ability to communicate the need for prevention—must be required qualifications for leaders in the twenty-first century.

In our world of unprecedented levels of destructive weaponry and increased geographic and social proximity, competition between groups has become extremely dangerous. In the century to come, human survival may well depend on our ability to learn a new form of adaptation, one in which intergroup competition is largely replaced by mutual understanding and human cooperation. Curiously, a vital part of human experience—learning to live together—has been badly neglected throughout the world.

It is not too late for us to develop a radically new outlook on human relations. Perhaps it is something akin to learning that the Earth is not flat. Through concerted educational efforts, such a shift in perspective throughout the world might at long last make it possible for human groups to learn to live together in peace and mutual benefit.

There is a very long evolutionary connection between human groups and their survival.

1

This basic fact has implications for conflict resolution and intergroup accommodation. During the past few decades, valuable insights have emerged from both field studies and experimental research on intergroup behavior. Among the most striking is the finding that the propensity to distinguish between in-groups and out-groups and to make harsh, invidious distinctions between "us" and "them" is a pervasive human attribute. Although these easily learned responses may have had adaptive functions beneficial to human survival, they have also been a major source of conflict and human suffering.

There is a very long evolutionary connection between human groups and their survival.

1

This basic fact has implications for conflict resolution and intergroup accommodation. During the past few decades, valuable insights have emerged from both field studies and experimental research on intergroup behavior. Among the most striking is the finding that the propensity to distinguish between in-groups and out-groups and to make harsh, invidious distinctions between "us" and "them" is a pervasive human attribute. Although these easily learned responses may have had adaptive functions beneficial to human survival, they have also been a major source of conflict and human suffering.

Is it possible for groups to achieve internal cohesion and self-respect and sustain legitimate and effective political communities without promoting hatred and violence in the process? The immense human capacity for adaptation should make it possible for us to learn to minimize harsh and hateful distinctions. A great deal of laboratory and field research tells us that we can indeed learn new habits of mind, in spite of our evolutionary legacy.

There are countless examples of human tolerance and cooperation. What are the conditions under which group relations can go one way or another? If we could answer such questions better, perhaps we could learn to tilt the balance toward cultures of peace.

We might begin by strengthening research on child development, to better understand the causes of prejudice and the dynamics of intergroup relations. This sort of inquiry can help achieve a deeper understanding of human behavior that bears upon the ultimate problems of war and peace.

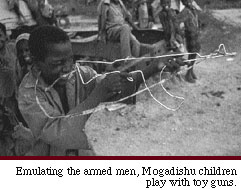

Current research is exploring practices within schools that can create a positive atmosphere of mutual respect and cooperative interactions among peers, as well as between students and teachers. In chapter 5, the valuable potential of educational institutions for preventing deadly conflict is emphasized. Teaching children the values of cooperation and toleration of cultural differences helps to overcome prejudicial stereotypes that opportunistic leaders routinely use for their own destructive ends. Tapping education's potential for toleration is an important and long-term task. It is necessary not only to strengthen the relevant curricula in schools and universities, but also to use the educational potential of popular media.

The Mass Media

A strong emphasis must be placed on freedom of the press—or the media in the broadest sense—with fair access for all parties, particularly for minority groups, and full freedom of political and cultural expression. This freedom also includes the opportunity to investigate governmental activities and to criticize all parties, even though the harshness of such criticism is often unpleasant and sometimes quite unfair.

How can the international community foster a mass media that is devoted to combating intergroup prejudice and ethnocentrism, as well as communicating the values and skills of conflict resolution? We are by now all too familiar with political entrepreneurs who use the media to exploit intergroup tensions—actions which often make their own constituencies as vulnerable as the groups that they target. Can these publics be reached by independent media? Radio is a relatively low-cost and widely accessible medium. As discussed in chapter 5, the international community should support radio and other independent media that combat divisive mythmaking by providing accurate information about current events, intergroup relations, and actual instances of conflict prevention.

Religious Institutions

Despite the fact that a belief in peace and brotherhood is professed by a wide variety of faiths, religious leaders frequently support and even incite intergroup violence. Today, we note with deep concern a growing fringe in many religions that is characterized by self-glorification on the one hand, and a bigoted, often fanatical, deprecation of "outsider" groups on the other. While clearly dangerous, such extremist orientations are seldom dominant. Indeed, both historically and today, the core creed of most religions tends to support social tolerance, respect for others, concern for the vulnerable, and the peaceful resolution of disputes. Moreover, as noted earlier, religious leaders throughout the world enjoy extensive popular confidence and influence in educational institutions.

Religious education has tended to focus narrowly on indoctrination in the history and theology of the faith. Typically, however, there also has been an ethical content that could serve as the basis for expanded efforts to address the moral and practical necessity for groups to learn to live together amicably. The international community should challenge religious leaders and institutions to examine these issues in their own way—in their schools, from their pulpits, and in their organizations.

The United Nations

Education for the peaceful management of conflict must not be confined by national boundaries. Here, the international community can play a decisive role in broadening public education on a whole range of problems associated with intergroup violence.

The UN is already the world's premiere institution for conflict resolution and is likely to become even more active in the decades ahead. Various UN organizations can provide invaluable leadership in educating policymakers and the general public about resolving conflicts without violence. It would be ambitious and unprecedented, but not entirely fanciful, for the UN to sponsor, for example, leadership seminars in cooperation with major universities or research institutes to which would be invited new heads of state, new foreign ministers, new defense ministers, and parliamentarians of varying groups and parties. On an on-going basis, such seminars could educate leaders about how the UN and other international organizations can help them establish more effective and inclusive institutions for addressing disputes. Given the contemporary climate, it is singularly important that such seminars deal with the problems of nationalism, ethnocentrism, and violence, and that they do so in a way that takes account of all available knowledge about conflict prevention.

The UN is already the world's premiere institution for conflict resolution and is likely to become even more active in the decades ahead. Various UN organizations can provide invaluable leadership in educating policymakers and the general public about resolving conflicts without violence. It would be ambitious and unprecedented, but not entirely fanciful, for the UN to sponsor, for example, leadership seminars in cooperation with major universities or research institutes to which would be invited new heads of state, new foreign ministers, new defense ministers, and parliamentarians of varying groups and parties. On an on-going basis, such seminars could educate leaders about how the UN and other international organizations can help them establish more effective and inclusive institutions for addressing disputes. Given the contemporary climate, it is singularly important that such seminars deal with the problems of nationalism, ethnocentrism, and violence, and that they do so in a way that takes account of all available knowledge about conflict prevention.

Through these seminars, as well as through its publications program and the wider media, the UN can make more accessible the world's accumulated experience with conflict and conflict prevention. In particular, the UN could serve as a storehouse of information about specific conflicts; the responsible handling of weapons of mass destruction; the likely consequences of unregulated weapons buildups; the skills, knowledge base, and prestige properly associated with successful conflict resolution; effective strategies for economic development, including innovative uses of science and technology for development; and lessons from cooperative behavior in the world community, including the peaceful management of disputes at the international level.

The UN system can make these resources and skills accessible to the world by creating a comprehensive information program in which important knowledge is provided to key policymakers on a regular basis. In the same vein, the UN can build an information network among community groups, nongovernmental organizations, academic institutions, and the corporate sector. In this way, accurate and credible information can be provided on both intergroup and interstate conflicts as well as on ways of managing them constructively.

One illustration of the potential for educational innovation is an initiative launched by UNESCO in May 1996 to promote tolerance, cooperation, and conflict prevention and resolution in schools. 2 The "Culture of Peace" has developed a conceptual framework that participating educational institutions in countries around the world will use to design their own education strategies. In addition to educational materials, curricula guides, and teacher training, the project emphasizes the importance of the values, attitudes, and behaviors of a culture of peace by ensuring that they are built into the social relations of the learning process itself. Pilot activities are focused on peaceful conflict resolution in schools serving communities where children live in violence-prone conditions. This effort could serve as a model for more widespread international initiatives. There is an urgent need for local, national, and international ingenuity in this field.

The international community can expand the range of favorable contacts between people of different groups and countries. A greater comprehension of other, often unfamiliar, cultures is essential to the reduction of negative preconceptions. To this end, educational, cultural, and scientific exchanges can have lasting value and should be encouraged. Likewise, the international community should seek to develop joint projects that allow more sustained cooperation across political and cultural borders. If only on a small scale, such endeavors offer the practical experience of working together in the pursuit of a superordinate, commonly beneficial goal. There are a number of ways to overcome antagonistic attitudes between groups and, preferably, to prevent them from arising in the first place. Thus far, however, societies have been remarkably inattentive to these possibilities.

Those who have a deep sense of belonging to groups that cut across ethnic, national, or sectarian lines may serve as bridges between different groups and help to move them toward a wider, more inclusive social identity. Building such bridges will require many people interacting across traditional barriers on a basis of mutual respect. Developing a personal identification with people beyond one's primary group has never been easy. Yet, broader identities are possible, and in the next century it will be necessary to encourage them on a larger scale than ever before.

Time and again, the Commission has returned to the indispensability of leadership. Without effective and responsible leadership, it would not be possible to implement the strategies and use the practical tools for preventing deadly conflict.

Mikhail Gorbachev, former president of the Soviet Union, reflected on his years of intense interaction with political leaders all over the world.

3

One of his more noteworthy observations was the pervasive tendency among leaders to view "brute force" as their ultimate source of validation. Gorbachev highlights the continuation of a long-standing—and historically deadly—inclination of leaders to reduce the art of leadership to being tough, aggressive, and even violent. Indeed, for all too many leaders, projecting an image of physical strength is still the essence of leadership. Although Gorbachev controlled a vast nuclear arsenal, as well as immense power in conventional, chemical, and biological weapons, he was wise enough not to interpret his own authority in terms of "brute force." Gradually, Gorbachev, as had then-U.S. President Ronald Reagan, took a great step forward by replacing the old security concept of nuclear superiority with an explicit endorsement of the principle that nuclear war can never be won and must never be fought.

Mikhail Gorbachev, former president of the Soviet Union, reflected on his years of intense interaction with political leaders all over the world.

3

One of his more noteworthy observations was the pervasive tendency among leaders to view "brute force" as their ultimate source of validation. Gorbachev highlights the continuation of a long-standing—and historically deadly—inclination of leaders to reduce the art of leadership to being tough, aggressive, and even violent. Indeed, for all too many leaders, projecting an image of physical strength is still the essence of leadership. Although Gorbachev controlled a vast nuclear arsenal, as well as immense power in conventional, chemical, and biological weapons, he was wise enough not to interpret his own authority in terms of "brute force." Gradually, Gorbachev, as had then-U.S. President Ronald Reagan, took a great step forward by replacing the old security concept of nuclear superiority with an explicit endorsement of the principle that nuclear war can never be won and must never be fought.

It will take unprecedented leadership skills to move the world toward the elimination of nuclear weapons. We still must confront the fact that a misjudgment or miscalculation brought about by the interplay of personal and mechanical foibles could lead to a nuclear disaster. As long as these weapons exist, so does this threat.

Although the prevention of deadly conflict requires many tools and strategies, bold leadership and an active constituency for prevention are essential for these tools and strategies to be effective. One of the central objectives of this Commission has been to help leaders to become better informed about the problems at hand and to suggest useful ways to respond to them. However, we recognize that raising leaders' awareness, although necessary, is not sufficient. We have also sought to offer practical measures by which leaders can be motivated, encouraged, and assisted to adopt a preventive orientation that is supported by the best knowledge and skills available.

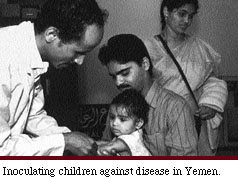

We believe that lessons learned in other contexts can be usefully applied to the prevention of deadly conflict. In the sphere of public health, the application of the concept of prevention is familiar. We believe this view of the prevention process offers a useful practical analogy. In much the same way that sustained medical research and conscientious public health practices have eliminated many deadly epidemics, we believe that the security and well-being of millions of people could be improved where knowledge, skill, and dedication are placed in the service of preventing deadly conflict.

We urge leaders to develop an explicit focus on prevention, not only elected officials, but also leaders in business, media, religion, and other influential communities. By virtue of both their power and public prominence, these leaders bear a serious responsibility for utilizing their public influence for constructive purposes. In both word and deed, they can shape an agenda for cooperation, caring, and decent human relations.

What kind of leadership are we talking about? While leadership for preventing deadly conflict is the specific focus of this report, we also have in mind a broader notion of leadership that encompasses effective, democratic governance, humanitarian values, and justice.

Lessons of World War II

In this century, we have witnessed abundant examples of leadership that was brutal and effective, as well as leadership that was decent but ineffective. The events leading to the carnage of World War II serve well to illustrate both of these variants of maladaptive leadership.

In the early 1930s, there were unmistakable signs that there would be a reign of terror if the National Socialists came to power in Germany. Adolf Hitler did not hide his brutality. He elaborated his foreign policy views in speeches and made his view on war especially clear in Mein Kampf in 1924. There were moments during Hitler's rise to power and in the years following when the international community could have taken preventive action. The atrocities of Hitler's storm troopers in his first months in office should have been a powerful warning: a regime that massively violates domestic law and egregiously violates human rights will create a similarly lawless foreign policy.

Why, then, in light of all these warnings, did leaders and publics around the world miscalculate, tolerate, and fatally fail to react to the danger posed by Hitler's rise to power in 1933? Why did the representatives of the leading democracies not make the connection between Hitler's brutal domestic and foreign policies? Why were they unwilling to confront the formidable danger posed by Hitler, despite his explicit threats and overt actions?

In part, the democracies did not react quickly to the early aggressive acts of totalitarian states because of their preoccupation with the Depression and the severe domestic hardships it created. The massive loss of life in World War I made leaders, especially of the established democracies, particularly anxious to avoid another war at almost any cost. Leaders readily invented excuses for acts of international lawlessness as well as for their own aversion to taking action to stop them. They deluded themselves with the idea that Hitler simply desired a revision of the Versailles Treaty and the restoration of Germany's 1914 boundaries. Once these terms were met, they hoped that Hitler would become a law-abiding citizen or that he would be a short-lived political phenomenon. Some thought he was capable of fomenting ill-will but not of ruling and that he would be replaced by more moderate power groups once the economic and political crisis in Germany was overcome. Citizens in democracies did not want to be burdened with additional problems, and they largely supported their leaders' passivity or appeasement.

Overall, world leaders blinded themselves to the acts of aggression, thereby actually enhancing the probability of another world war. There is a powerful lesson in the ubiquitous human capacity for wishful thinking in the face of danger. Tragically, such thinking led the world to neglect numerous opportunities to prevent the horrific catastrophes of genocide and war that followed.

The grim lessons of prewar diplomacy alert us to the profoundly important and sometimes negative role played by the responses of leaders to early warning. Fanatical, ruthless, and otherwise highly dangerous leaders must be checked before they become so powerful that stopping them requires massive armed intervention. With strong responses to Hitler's aggression, World War II and the Holocaust could have been prevented.

The Vision of Nelson Mandela

Yet there are many leaders who are capable of learning, of acting creatively and effectively in the face of new dangers and new opportunities, and of accommodating the legitimate concerns of rival groups. 4 There is perhaps no better example of this kind of courageous and visionary leader than Nelson Mandela.

During his many years as a political prisoner, Mandela experienced firsthand what it meant to have legitimate aspirations constantly frustrated by arbitrary power. He had ample reason for anger and a tempting motive for retaliation. Indeed, he could have pursued his political aims through violent means. Instead, reflection led him to a different conclusion: while violent struggle might indeed destroy his adversaries, in the process it might also destroy his own people—physically as well as morally. As we noted in chapter 2, Mandela thus came to embrace reconciliation, negotiated solutions to political differences, and the joint creation of mutually beneficial arrangements. From a different starting point, F.W. de Klerk underwent a transformation of his own. Together, the two men were able to generate a process of peaceful regime change in South Africa that avoided massive violence, despite the social and political tensions that apartheid had created.

During his many years as a political prisoner, Mandela experienced firsthand what it meant to have legitimate aspirations constantly frustrated by arbitrary power. He had ample reason for anger and a tempting motive for retaliation. Indeed, he could have pursued his political aims through violent means. Instead, reflection led him to a different conclusion: while violent struggle might indeed destroy his adversaries, in the process it might also destroy his own people—physically as well as morally. As we noted in chapter 2, Mandela thus came to embrace reconciliation, negotiated solutions to political differences, and the joint creation of mutually beneficial arrangements. From a different starting point, F.W. de Klerk underwent a transformation of his own. Together, the two men were able to generate a process of peaceful regime change in South Africa that avoided massive violence, despite the social and political tensions that apartheid had created.

The same kind of leadership was responsible for the peaceful conclusion of the Cold War. The evolution of relations between Reagan and Gorbachev was similar to that of Mandela and de Klerk. During the course of their complicated—and often uneasy—negotiations, they too moved to embrace mutually supportive positions. Both of these examples are highly suggestive of the decisive role that bold and enlightened leadership can play in avoiding catastrophe and building better relations, both between and within states.

Especially at a time when many countries are struggling with the new and uncertain challenges of democratization, the international community must champion the norm of responsible leadership and support opportunities for leaders to engage in negotiated, equitable solutions to intergroup disputes. Leaders who demonstrate good-will and who engage in these practices should be recognized and rewarded. By the same token, conditions should be fostered that would allow electorates to hold their leaders accountable when and where they depart from democratic norms of peaceful conflict resolution. The international community must expand efforts to educate publics everywhere that preventing deadly conflict is both necessary and possible. To miss the opportunity for preventive action is a failure of leadership.

Both the complexity and risk of taking action in many dangerous situations today highlight the need to share burdens and pool strengths. The task can be made more feasible by strengthening institutional arrangements to improve decision-making processes.

Both the complexity and risk of taking action in many dangerous situations today highlight the need to share burdens and pool strengths. The task can be made more feasible by strengthening institutional arrangements to improve decision-making processes.

In the search for sound and meaningful policies, certain trade-offs are inevitable. There are two competing constraints in particular that impinge on leadership choices and that very often create insoluble policy dilemmas. To be effective, leaders must be sensitive to these constraints and use careful judgment. The first constraint is the need to create and sustain a modicum of policy consensus, both within the various branches of government and among the public at large. A second constraint stems from the finite nature of policymaking resources, both tangible financial and personnel resources and more intangible resources such as time and clear mandate. The careful, systematic search for a comprehensive policy should not preclude a timely decision; an unduly protracted search could reduce the likelihood of a successful outcome. Likewise, any investment of time and policymaking resources in support of one policy may interfere with the implementation of other, often equally important, measures.

Organizational, procedural, and staff arrangements that support decision making can be institutionalized in ways that foster these problem-solving processes. The many recommendations emerging from studies of effective policymaking apply to efforts to prevent deadly conflict. 5 These studies suggest there are ways to ensure that leaders receive high-quality information, analysis, and advice, and avoid omissions in surveying objectives and alternatives.

There are five tasks that must be well executed within a policymaking system if the leader is to receive information, analysis, and advice of high quality.

6

These procedures do not guarantee high-quality decisions, but they increase their probability. The first task is to ensure that sufficient information about the current situation is obtained and analyzed adequately. Second, the policymaking process must facilitate consideration of all the major values and interests affected by the policy issue at hand. Third, the process should ensure a search for a relatively wide range of options and a reasonably thorough evaluation of the expected consequences of each. Fourth, the policymaking process should carefully consider the problems that might arise in implementing the options under consideration. Finally, the process should remain receptive to indications that current policies are not working: it is important to retain the capacity to learn rapidly from experience.

These procedures do not guarantee high-quality decisions, but they increase their probability. The first task is to ensure that sufficient information about the current situation is obtained and analyzed adequately. Second, the policymaking process must facilitate consideration of all the major values and interests affected by the policy issue at hand. Third, the process should ensure a search for a relatively wide range of options and a reasonably thorough evaluation of the expected consequences of each. Fourth, the policymaking process should carefully consider the problems that might arise in implementing the options under consideration. Finally, the process should remain receptive to indications that current policies are not working: it is important to retain the capacity to learn rapidly from experience.

In crisis situations requiring operational prevention, where decisions must be made quickly in response to unanticipated threats, decision-making hazards are often amplified. Crisis decision making normally encounters a variety of additional constraints, including the moral complexity of making life-or-death choices and the psychological stress of working with incomplete information in changing and uncertain conditions, where time and viable options are scarce. Very often, the gravity of the crisis means that long-term consequences are discounted in favor of short-term objectives.

To overcome these obstacles, leaders should seek to mobilize the best available information by relying on well-informed advisers with different perspectives and encouraging an atmosphere of candid expression. In this way, they can ease the difficulties of differentiating between possible and probable courses of action, of appraising the costs and benefits of alternative policies, and of distinguishing relevant from irrelevant information. Thus, decision makers can be better equipped to cope with ambiguity, to refrain from impulsive action, and to respond flexibly to new developments.

It is important for leaders to take into account the powerful phenomenon of wishful thinking, in which individuals hear what they want to hear because they deeply wish it were true. Crisis situations are almost always complex and ambiguous. This ambiguity can be read in wishfully inaccurate ways and with wildly disappointing results. World War I, for example, began with an anticipation on both sides of quick and glorious victories, only to end several years later in the unprecedented destruction of Europe.

Naturally, in deciding whether and how to participate in preventive efforts, leaders must consider national interests. Traditionally, national interests have been narrowly conceived in terms of vital geopolitical or military advantage and have been invoked to defend against clear and present military or economic threats.

The Commission believes that, on the eve of the twenty-first century, there is a need for a broader conception of national interests, one which encompasses both enlightened self-interest and a realistic appraisal of the contemporary world. When every violent conflict is dismissed as distant and inconsequential, we run the risk of allowing a series of conflict episodes to undermine the vitality of hard-won international norms. In a world of increased economic and political interdependence, in which national well-being increasingly depends on the security and prosperity of other states and peoples, indifference of this sort could have corrosive and consequential effects for everyone. Rather than rely on obsolete notions of national interest, leaders must develop formulations that reflect this new reality.

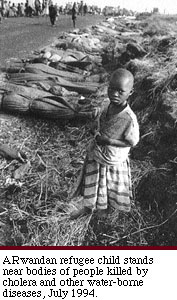

We have noted earlier the risks of mass violence growing out of degraded conditions: the fostering of hatred and terrorism, of infectious pandemics, of massive refugee flows, of dangerous environmental effects. All these risks must be taken into account in a world of unprecedented proximity and interdependence. They will have a bearing on realistic appraisals of national interest and the interest of the international community in the next century.

From this perspective, the Commission strongly believes that preventing deadly conflict serves the most vital human interest—that of survival. Clearly, any effort to promote the norms of tolerance, mutual assistance, responsible leadership, and social equity is valuable in its own right. But the prevention of deadly conflict has a practical as well as a moral value: where peace and cooperation prevail, so do security and prosperity. Witness the steps taken after World War II, which laid the groundwork for today's flourishing European Union. Leaders such as Jean Monnet and George Marshall looked beyond both the wartime devastation and the enmities that had caused it, and envisioned a Europe in which regional cooperation would transcend adversarial boundaries and traditional rivalries. Correctly, they foresaw that large-scale economic cooperation would facilitate not only the postwar recovery but also the long-term prosperity which has helped Europe to achieve a degree of peace and security once thought unattainable. Postwar reconstruction is an excellent example of building structural prevention by creating conditions that favor social and economic development and peaceful interaction. A long-range vision and a broad view of regional opportunities can be exceedingly constructive.

Realizing this vision was not easy. It required constant and creative efforts to educate the public, mobilize key constituencies, and persuade reluctant partners. Moreover, maintaining this support required the prudent use of scarce political and social capital. To take just one example, the Marshall Plan initially enjoyed very little support among the American public. Had it not been for the determination and skill of President Harry Truman, the program that made the single most important contribution to Europe's postwar reconstruction and development would probably never have been implemented. The Marshall Plan is a model of what sustained international cooperation can accomplish; no less, it is an extraordinary illustration of the decisive importance of visionary and courageous leadership.

One of the greatest obstacles to the creation of an enduring framework for preventive action is the human aversion to risk. Indeed, as with every new policy initiative, the prevention of conflict involves uncertainty and risk. Even the most well-designed and carefully coordinated preventive action can fail to achieve every objective. Very often, the results of prevention may be difficult to measure or may take considerable time to materialize. This means that leaders who bear the risk of undertaking new initiatives may no longer be in power when the time comes to claim the rewards of their success. Especially in pluralistic polities, leaders must in the meantime confront accusations that preventive missions waste resources or place military personnel in conditions of unnecessary risk, while achieving little. In view of all these hazards, how can leaders summon the determination and maintain the political will to act preventively?

One way is for leaders to focus on generating a broad constituency for prevention. With a public that is aware of the value of prevention and informed of the availability of constructive alternatives, the political risks of sustaining preemptive engagement in the world are reduced. In practical terms, an enduring constituency for prevention could be fostered through measures that: identify latent popular inclinations toward prevention; reinforce these impulses with substantive explanations of rationales, approaches, and successful examples; make the message clearer by developing analogies from familiar contexts such as the home and community; and demonstrate the linkage between preventing deadly conflict and vital public interests. Such efforts are more likely to succeed if leaders can mobilize the media, the business community, and other influential and active groups in civil society.

Among the general public, there are already a range of dispositions, interests, and organizations that can be tapped for support. For example, as mentioned earlier, in a variety of democratic countries, a strong constituency for prevention in medicine and public health has emerged over the last several decades. Public awareness campaigns and the provision of information about health risks and preventive behavior have led to remarkable improvements in public health. Concepts like "an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure" have taken hold in the public imagination and are reflected positively in improved rates of immunization, better diet and exercise practices, and reduced cigarette smoking. In short, sustained public efforts at disease prevention have proven highly effective. This model of dedicated leadership and public education can be usefully applied to the prevention of deadly conflict. Earlier in this century, for example, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt employed a similar approach, utilizing familiar examples, to make the imperative of international cooperative security during and after World War II meaningful for the American people. This strategy helped the United States to overcome domestic isolationist sentiments.

Community fire prevention provides another useful analogy. To put out fires early, one needs operational tools like fire alarms, reliable telephones, adequate supplies of water and firefighting equipment, and well-trained professionals. When it comes to the structural conditions under which fires are likely to occur, still other tools are needed—for example, specialized knowledge about hazardous substances and the skills to dispose of them safely, and public education about the perils of high-risk behavior. In short, effective firefighting requires both a ready stock of skills and tools as well as a long-term culture of prevention. The Commission is interested in putting out the fires of deadly conflict when they are small, before they get out of hand. But we are also concerned with eliminating conditions that make these fires likely in the first place.

In the past few years, there has been some concern about the United States reverting to the isolationist posture of the post-World War I era and forsaking the active internationalist role that it has performed so successfully since World War II, when U.S. leadership was instrumental in the creation of the UN, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and NATO. Yet, careful analysis of recent survey research shows that popular opinion does not warrant this conclusion. 7 As in a number of other countries, the public is deeply aware of the wider world and is urging the government to assume greater international responsibilities.

Survey research indicates that the American public is not becoming parochial and isolationist in the post-Cold War era—a large majority of Americans continues to support U.S. involvement in international affairs. 8 But the American public does not support the idea of America acting as the "world's policeman" or global hegemon. Americans would prefer to see a revival of the kind of cooperative leadership and collective security that the United States demonstrated in supporting the creation of the UN.

Americans also support the development of the United Nations as the primary vehicle for international action. 9 They believe that the protection of human rights and the maintenance of global security are best achieved through collective efforts. Indeed, most Americans wish to see the United States assume a shared leadership role in multilateral organizations, including, where needed, participating in multilateral military interventions. Polls also show that Americans support foreign aid, particularly when it is used for humanitarian purposes. 10

In the United States, as in many other countries, a nascent constituency for preventing deadly conflict already exists. To develop this constituency, leaders and their publics need an improved understanding of both the problems and the range of available solutions addressed by this Commission. These solutions—it bears repeating—call for the pooling of each country's respective strengths and an equitable sharing of burdens.

Consideration of contemporary public attitudes in the U.S. has led one scholar to elaborate a practical strategy for constituency building. 11 The key component of this strategy is the creation of an educational program that expressly addresses popular concerns about international involvement. As with people everywhere, most people in the industrialized democracies are concerned with the economic and social problems of daily life. They are perplexed by the rapid changes in the global economy and fearful of the potential for greater unemployment and a widened gap between rich and poor. They also tend to be suspicious of leadership priorities, believing that leaders are often more interested in advancing their own political careers than in promoting public interests. Many people are uneasy about international commitments because of concerns that the costs may be too high and the problems too difficult. Thus, leaders must work to clarify the links between the prevention of deadly conflict and domestic well-being. They must demonstrate to the public that preventive action, whether operational or structural in focus, is both cost-effective and able to generate desired results.

The twentieth century has witnessed some of the bloodiest, most destructive wars in recorded history. As the world approaches the eve of the third millennium, many unresolved intergroup and interstate conflicts continue to fester and to claim a massive toll in human lives and resources. For too long now, we have deluded ourselves with the complacent belief that the events in faraway lands are not our concern, that the problems of other peoples do not have consequences for us all. This short-sighted view has left us ill prepared to deal with conflicts when they occur. It has condemned us to muddle through from crisis to crisis, applying emergency first aid where what is most urgently needed are more fundamental solutions. This report has endeavored to show that we can indeed prevent deadly conflict—perhaps not easily, perhaps not quickly, but the capacity is within our grasp.

The record of this century also provides a compelling basis for hope. The decline of tyranny and the expansion of representative and responsive government, the protection of human rights, and the promotion of social justice and economic well-being—imperfect and incomplete though they are—suggest what human ingenuity can accomplish. If we are to lessen the destructiveness of humankind, we must pool our strengths to extend these achievements in the century to come. By placing the promise of prevention squarely at the forefront of the world's agenda, it is the hope of this Commission that leaders and publics will take up the challenges of education, leadership, and communication. Perhaps then we can achieve together the peace that has so far eluded us separately.

Notes

Note 1: This section draws upon research into human conflict and education over the past several decades. See, for example, David Hamburg, "An Evolutionary Perspective on Human Aggression," in The Development and Integration of Behavior: Essays in Honor of Robert Hinds, ed. P. Bateson, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991); B. Smuts, D. Cheney, et al., Primate Societies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986); M. Brewer and R. Kramer, "The Psychology of Intergroup Attitudes and Behavior," Annual Review of Psychology 36 (1985), pp. 219-243; A. Bandura, Aggression: A Social Learning Analysis (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1973); D. T. Campbell, " Ethnocentric and Other Altruistic Motives," in Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, ed. D. T. Campbell (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965); G. Allport, The Nature of Prejudice (New York: Doubleday, 1958); J. Groebel and R. Hinde, Aggression and War: Their Biological and Social Bases (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989); W. D. Hawley and A. W. Jackson, eds., Toward a Common Destiny: Improving Race and Ethnic Relations in America (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1995); E. Staub, The Roots of Evil: The Origins of Genocide and Other Group Violence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989); M. Deutsch, The Resolution of Conflict (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1973). Back.

Note 2: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, "A Culture of Peace and Nonviolence within Educational Institutions: Elements for the Launching of an Interregional Project," draft paper prepared November 23, 1995. UNESCO publishes newsletters and other information on the Culture of Peace programs on its website: http://www.unesco.org/cpp/ Back.

Note 3: Mikhail Gorbachev, "On Nonviolent Leadership," in Leadership (Washington, DC: Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict, forthcoming). Back.

Note 4: Boutros Boutros-Ghali, "Leadership and Conflict," in Leadership (Washington, DC: Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict, forthcoming). Back.

Note 5: For a sampling of the literature regarding bureaucratic decision making, primarily in the U.S., see Carnes Lord, The Presidency and the Management of National Security (New York: The Free Press, 1988); Robert L. Pfaltzgraff, Jr. and Jacquelyn K. Davis, National Security Decisions: The Participants Speak (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1990); D.A. Welch, "The Organizational Process and Bureaucratic Politics Paradigms: Retrospect and Prospect," International Security 17 (Fall 1992), pp. 112-146; Scott Sagan, "The Perils of Proliferation," International Security 18 (Spring 1994), pp. 66-107; E. Rhodes, "Do Bureaucratic Politics Matter?" World Politics 47 (October 1994), pp. 1-41; Irmtraud N. Gallhofer and Willem E. Saris, Foreign Policy Decision-Making (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1996); Irving L. Janis, Crucial Decisions: Leadership in Policymaking and Crisis Management (New York: The Free Press, 1989), pp. 28-33. Back.

Note 6: Alexander L. George, Presidential Decisionmaking in Foreign Policy: The Effective Use of Information and Advice (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1980), pp. 1-12. Back.

Note 7: Steven Kull, "What the Public Knows that Washington Doesn't," Foreign Policy 101 (Winter 1995-1996), pp. 102-115. Back.

Note 8: Steven Kull and I.M. Destler, An Emerging Consensus: A Study of American Public Attitudes on America's Role in the World: Summary of Findings (College Park, MD: Program on International Policy Attitudes, Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland, 1996), p. 1. Back.

Note 9: Catherine McArdle Kelleher, "Security in the New Order: Presidents, Polls, and the Use of Force," in Beyond the Beltway: Engaging the Public in U.S. Foreign Policy, eds. Daniel Yankelovich and I.M. Destler (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1994), pp. 238-239. Back.

Note 11: Daniel Yankelovich and John Immerwahr, "The Rules of Public Engagement," in Beyond the Beltway: Engaging the Public in U.S. Foreign Policy, eds. Daniel Yankelovich and I.M. Destler (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1994), pp. 43-77. Back.