|

|

|

|

Final Report With Executive Summary

Carnegie Corporation of New York

1997

6. Preventing Deadly Conflict

The Responsibility of the United Nations and Regional Arrangements

The UN is a unique, comprehensive forum for collective security and world dialogue. Serving not as a world government but as a clearinghouse for a worldwide network of human services on behalf of all people—the affluent as well as the desperately poor—the UN today is on the threshold of a new period in its history: no longer a hostage to Cold War bickering, it has moved to establish a fresh sense of its role and purpose.

The UN has already made considerable progress toward fulfillment of some of the aspirations of member states—greater security between states, decolonization, economic and social development, protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms, and, in general, cooperation among nations on common approaches to global problems. The UN has served to legitimize the engagement of member states in coping with crises, and, on occasion, has undertaken challenging responsibilities that member states cannot or will not shoulder individually.

The UN has already made considerable progress toward fulfillment of some of the aspirations of member states—greater security between states, decolonization, economic and social development, protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms, and, in general, cooperation among nations on common approaches to global problems. The UN has served to legitimize the engagement of member states in coping with crises, and, on occasion, has undertaken challenging responsibilities that member states cannot or will not shoulder individually.

The UN has, at times, however, appeared to be little more than a discordant association of sovereign states. Both in practical endeavors and in efforts to reform the organization, the UN has frequently come up against governments' concern to protect national sovereignty and a deep, if unexpressed, reluctance to countenance any development in the direction of supranationalism.

These two images of the UN—a successful, practical (indeed, necessary) organization or a group of quarreling states—again point up one of the fundamental conclusions of this report. The main responsibility for addressing global problems, including deadly conflict, rests on governments. Acting individually and collectively, they have the power to work toward solutions or to hinder the process. The UN, of course, is only as effective as its member states allow it to be.

The UN can be an an essential focal point for marshaling the resources of the international community to help prevent mass violence. No single government, however strong, and no nongovernmental organization can do all that needs doing—nor should they be expected to. To be sure, the involvement of the UN in conflict management in the post-Cold War period has brought it much criticism, both just and unjust. 1 In Rwanda, for example, as was discussed in the prologue to this report, the Security Council withdrew forces at perhaps the worst possible moment. But some of the failings of the UN reflect, among other things, the very real concerns of member states regarding unwanted intrusion into national sovereignty. These concerns have sometimes inhibited efforts to anticipate and respond to incipient violence, especially within states. In particular, these concerns have played a role in thwarting attempts so far to set up a standing rapid reaction force. One of the UN's greatest challenges is whether and how to adapt its mechanisms for managing interstate disputes to deal with intrastate violence. If it is to move in this direction, it must do so in a manner that commands the trust of the membership and their voluntary cooperation.

Strengths of the UN

As the sole global collective security organization, the UN's key goals include the promotion of international peace and security, sustainable economic and social development, and universal human rights. Each of these goals is relevant to the prevention of deadly conflict.

The global reach and intergovernmental character of the UN give it considerable influence, especially when it can speak with one voice. The Security Council has emerged as a highly developed yet flexible mechanism to help member states cope with a remarkable variety of problems. The Office of the Secretary-General has considerable prestige, convening power, and the capacity to reach into problems early when they may be inaccessible to governments or private organizations. Many of the UN's functional agencies, such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the World Food Program (WFP), the World Health Organization (WHO) and, for that matter, the Bretton Woods financial institutions—the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (more commonly known as the World Bank) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—conduct effective programs of great complexity around the world.

The UN system is vital to any effort to help prevent the emergence of mass violence. Its long-term programs to reduce the global disparity between rich and poor and to develop the capacity of weak governments to function more effectively are of fundamental importance to its role.

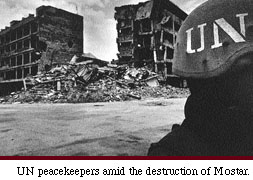

Member states have often used the Security Council, and sometimes the General Assembly, to address rapidly unfolding crises. In the Middle East, Africa, Cyprus, South Asia, Cambodia, Central America, and elsewhere, the UN has developed a number of innovative practices—observer missions, peacekeeping, massive humanitarian actions, special representatives of the secretary-general, election organization and monitoring, and human rights support—to address a wide range of potentially deadly disputes. Partly as a result of these efforts, the UN has had important successes in averting crises, preventing the further deterioration of crises, and ending hostilities. 2

The UN gives a voice to all member states, large and small, and provides a forum for their voices to be heard on a wide range of concerns. In addition, many critical issues—such as apartheid and Palestinian rights—have been kept alive and debated at the UN in the search for a solution.

Providing an open forum gives the UN an early awareness of incipient troubles, a possibility for warning that those troubles may be taking a turn for the worse, a means—through dialogue and information sharing—to clarify dangerous situations, and ways, through the Security Council, the General Assembly, the Office of the Secretary-General, and the various UN agencies, to develop effective responses. The UN has also proved valuable as an organization through which states could deal with many kinds of problems that transcend national and regional boundaries and that lay beyond the capacity of any single member to handle alone. In this way, the UN has addressed such global concerns as disarmament and arms control, the environment, population, health, illegal drugs, the plight of children, the inequality of women, and human rights. Global agreement in many of these fields has emerged from UN initiatives, and the UN remains heavily engaged in the ongoing work (see Box 6.1). 3

|

In 1996, for example, UNICEF launched its "Anti-War Agenda" to lessen the suffering of children as a result of mass violence. The agenda's top priority is prevention with special emphasis on the protection of girls and women, rehabilitation of child soldiers, a ban on recruitment of children under 18 years of age, a ban on land mines, aggressive prosecution of war crimes, establishment of "zones of peace" to create humanitarian outposts in conflict, and a requirement that a "child impact statement" be drafted before sanctions are imposed. The agenda also stresses the need to prevent and treat the psychological trauma that children suffer as a result of war and the importance of education to promote tolerance and peaceful means of dispute resolution. 4

The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees was created in 1951 primarily to protect individuals forcibly displaced by World War II and the creation of the Iron Curtain. For its first 40 years, UNHCR operated essentially in countries of asylum, but by the mid-1980s it was increasingly being asked to assist internally displaced persons (IDPs), those in refugee-like situations who had not crossed an international frontier. These humanitarian crises, which averaged five per year until 1989, suddenly jumped to 20 in 1990 and to 26 in 1994. By the end of 1996, there were an estimated 20 million IDPs worldwide and about 16 million refugees, and UNHCR's budget over the past 20 years has increased twentyfold. 5

UNHCR is under constant pressure by governments to do more. As its responsibilities have expanded, its traditional mission of protection has come under strain from the demands of providing relief and repatriation, as was painfully evident in the so-called safe havens in Bosnia and the terrorized Rwandan refugee camps of Eastern Zaire. High Commissioner Sadako Ogata has called on governments to strengthen the UN's capacity to protect and care for refugees and IDPs, including, where necessary, providing multilateral security forces to protect UN-mandated humanitarian operations—steps the Commission endorses.

Its intergovernmental character gives the UN real value and practical advantages for certain kinds of early preventive action—such as discreet, high-level diplomacy—that individual governments do not always have. Here, the Office of the Secretary-General has proven particularly valuable on a wide array of world problems in need of international attention. The secretary-general has brought to the attention of the Security Council early evidence of threats to peace, genocide, large flows of refugees threatening to destabilize neighboring countries, evidence of systematic and widespread human rights violations, attempts at the forcible overthrow of governments, and potential or actual damage to the environment. The secretary-general has also helped forge consensus and secure an early response from the Security Council by deploying envoys or special representatives, assembling a group of "friends" to concentrate on a particular problem, and by speaking out on key issues such as weapons of mass destruction, environmental degradation, and the plight of the world's poor (see Box 6.2). 6

|

Limitations of the UN

The features that give the UN its potential often come at a price. Its global reach often demands some sacrifice of efficiency and focus, and the UN is, of course, fully dependent on its membership for political legitimacy, operating funds, and personnel to staff its operations and carry out its mandates (see Box 6.3). Moreover, it is ironic that many states, while quick to turn to the UN to seek consensus for action in a crisis, are slow to provide resources for the action they demand and the missions they develop.

|

For its part, the Security Council can have a powerful voice in legitimizing or condemning state action. Yet, some aggressive states remain defiant, a situation that results from an erosion of the authority of the Security Council, and sometimes the consequences of ill-conceived, underfunded, underequipped, or poorly executed operations. This erosion of authority points to the need to reform the Security Council by making it more representative of the member states of the UN and worthy of their trust.

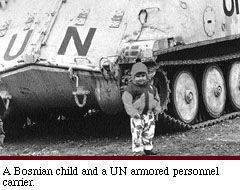

While member states seem in broad agreement that the UN should be concerned with a wide range of issues, there is far less agreement on what exactly the organization should do. Many countries, including some of the most powerful, use the UN as a fig leaf and a scapegoat, to blur unwanted focus, to defuse political pressure, or to dilute or escape their own responsibilities. States—again, even the most powerful—make commitments in the abstract, yet fail to honor them in practice. The 1993 resolution by the Security Council to protect several cities in Bosnia as "safe-areas" is a case in point. Against the advice of many experts and the warning of the secretary-general, the Security Council resolved to protect Gorazde, Sarajevo, Srebrenica, and several other cities and towns, and it authorized UNPROFOR under Chapter VII of the UN Charter to use "all measures necessary" to keep citizens secure. But it refused to provide the forces or the resources to carry out this mission, and the results were disastrous. 7 Assigning difficult missions but failing to provide adequate resources or authority for their implementation must not continue if the UN is to remain useful as an instrument of preventive action. 8

Despite the lack of agreement on engagement in domestic conflicts by international organizations, the UN has been required to intervene in several. It shepherded the transition from war to peace in Cambodia, helped broker solutions to conflicts in new states such as Bosnia and Georgia, marshaled an unprecedented humanitarian relief effort in Somalia, and dealt with refugees from the mass slaughter in Rwanda.

With the increasing number of conflicts within states, the international community must develop a new concept of the relationship between national sovereignty and international responsibility. As former Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali has observed:

| Respect for [states'] fundamental sovereignty and integrity [is] crucial to any common international progress. The time of absolute and exclusive sovereignty, however, has passed; its theory was never matched by reality. It is the task of leaders of states today to understand this and to find a balance between the needs of good internal governance and the requirements of an ever more interdependent world. 9 |

Echoing this theme, the Commission on Global Governance has noted:

| Where people are subjected to massive suffering and distress...there is a need to weigh a state's right to autonomy against its people's right to security. Recent history shows that extreme circumstances can arise within countries when the security of people is so extensively imperilled that external collective action under international law becomes justified. 10 |

The Commission on Global Governance has proposed a specific UN Charter amendment to authorize such action. However, as we already noted, there has been some tacit willingness in recent years to rely on liberal interpretations of the Charter language of "threats to international security," reinforced by the concept of "human security" and placing particular emphasis on human rights responsibilities. Nonetheless, questions of sovereignty and the role of outsiders remain extremely sensitive and controversial in many countries. The existing language of Article 2 (7) of the UN Charter written 50 years ago, states an important principle:

Nothing contained in the present Charter shall authorize the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state or shall require the Members to submit such matters to settlement under the present Charter; but this principle shall not prejudice the application of enforcement measures under Chapter VII.

This provision was one of the features of the Charter that made it possible for a wide range of governments to endorse it in 1945. While states at that time recognized the role that the most powerful among them might play to help prevent a third World War (hence the inclusion of Chapter VII provisions for "all means necessary"), they also recognized that weaker states needed a safeguard against encroachments by the strong. Now with the current waning of interstate conflict and the massive increase of intrastate violence, the demand for action has forced states to reinterpret, in practice at least, the meaning of this provision.

This provision was one of the features of the Charter that made it possible for a wide range of governments to endorse it in 1945. While states at that time recognized the role that the most powerful among them might play to help prevent a third World War (hence the inclusion of Chapter VII provisions for "all means necessary"), they also recognized that weaker states needed a safeguard against encroachments by the strong. Now with the current waning of interstate conflict and the massive increase of intrastate violence, the demand for action has forced states to reinterpret, in practice at least, the meaning of this provision.

The contradiction between respecting national sovereignty and the moral and ethical imperative to stop slaughter within states is real and difficult to resolve. The UN Charter gives the Security Council a good deal of latitude in making such decisions, but it also lays out a number of broad principles to guide the application of these decisions. The responsibility for determining where one principle or the other is to prevail resides with the Security Council and the member states on a case-by-case basis. Again, it is precisely the sensitivity of such a responsibility that has led to the growing demand for reform of the Security Council in order to make it more representative of the membership and more legitimate in the discharge of its responsibilities.

Strengthening the UN for Prevention

The Commission believes that the UN can have a central, even indispensable, role to play in prevention to help governments cope with incipient violence and to organize the help of others. Its legitimating function and ability to focus world attention on key problems, combined with the considerable operational capacity of many of its operating agencies, make it an important asset in any prevention regime. Yet certain reforms are necessary to strengthen the UN for preventive purposes. In a major statement on reform, Secretary-General Kofi Annan acknowledged this key responsibility of the UN and the need for a comprehensive approach to adapting the organization to meet this responsibility.

| The prevalence of intra-state warfare and multi-faceted crises in the present period has added new urgency to the need for a better understanding of their root causes. It is recognized that greater emphasis should be placed on timely and adequate preventive action. The United Nations of the twenty-first century must become increasingly a focus of preventive measures. 11 |

He outlines a number of measures to strengthen the UN to assume this role, including, for example:

More is necessary, however. The Commission believes that the secretary-general should play a more prominent role in preventing deadly conflict through several steps: more frequent use of Article 99 to bring potentially violent situations to the attention of the Security Council and, thereby, to the international community; greater use of good offices to help defuse developing crises; and more assertive use of the considerable convening power of the Office of the Secretary-General to assemble "friends" groups to help coordinate the international response.

In addition, the Commission believes that:

|

Such measures, together with those offered by the secretary-general and others contained in this report, would go a long way toward establishing a prevention orientation in the international community and laying the groundwork to develop standard practices that link UN actions with those of governments and NGOs.

Reform of the Security Council

There is a compelling need to enlarge and modernize the Security Council to ensure that its membership reflects the world of today rather than 1945. * There is almost universal agreement to that effect among the UN member states, but agreement about how precisely this objective might be accomplished has so far proved elusive for several reasons: the Security Council must not be unworkably large; there is no readily achievable consensus as to which major countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America should have permanent membership status; and the existing five permanent members are not likely to abandon or dilute their present veto power. One promising proposal is that put forward by Malaysian Permanent Representative, Tan Sri Razali Ismail, during his term as president of the General Assembly (see Box 6.4). The Commission proposes to remove the prohibition on election of any new nonpermanent members for successive terms from the Charter, enabling other major powers with aspirations to continuous or recurring membership to negotiate their reelection on a continuous or rotating basis.

|

On July 17, 1997, the Clinton administration joined the debate on Security Council reform by announcing a proposal to add five new permanent members—Germany and Japan plus three developing countries—to be selected by an unspecified process. As in the Razali proposal, none of the new members would be allowed a veto. The United States would, however, limit the size of the Council to no more than 20 or 21 seats, at least three less than the total recommended by Ambassador Razali.

On July 17, 1997, the Clinton administration joined the debate on Security Council reform by announcing a proposal to add five new permanent members—Germany and Japan plus three developing countries—to be selected by an unspecified process. As in the Razali proposal, none of the new members would be allowed a veto. The United States would, however, limit the size of the Council to no more than 20 or 21 seats, at least three less than the total recommended by Ambassador Razali.

In the Commission's view, the addition of new members should reflect not only the world's capacities but also the world's needs. The Commission believes that any arrangement should be subject to automatic review after ten years. The use of size, population, GDP, and level of international engagement (measured, for example, through such indices as participation in UN peacekeeping) might serve as criteria for permanent membership (see Table 6.1). The language of Article 23 of the UN Charter is worth recalling also, in its statement of appropriate criteria for any member of the Security Council, requiring that due regard be paid "for the contribution...to the maintenance of international peace and security and to the other purposes of the organization and also to equitable geographical distribution."

|

The Commission is under no illusion that any model will satisfy every member state. Despite the difficulties, it is crucial for agreement on reform to be reached quickly. Every year that the Security Council continues with its present structure, the UN suffers because the increasingly apparent lack of representativeness of the council membership diminishes its credibility and weakens its capacity for conflict prevention.

The Commission is under no illusion that any model will satisfy every member state. Despite the difficulties, it is crucial for agreement on reform to be reached quickly. Every year that the Security Council continues with its present structure, the UN suffers because the increasingly apparent lack of representativeness of the council membership diminishes its credibility and weakens its capacity for conflict prevention.

The UN's Role in Long-Term Prevention

The long-term role of the UN in helping to prevent deadly conflict resides in its central purposes of promoting peace and security, fostering sustainable development, inspiring widespread respect for human rights, and developing the regime of international law. Three major documents combine to form a working program for the UN to fulfill these roles: An Agenda for Peace, published in 1992; An Agenda for Development, published in 1995; and An Agenda for Democratization, published in 1996. Each report focuses on major tasks essential to help reduce the global epidemic of violence, preserve global peace and stability, prevent the spread of weapons of mass destruction, promote sustainable economic and social development, champion human rights and fundamental freedoms, and alleviate massive human suffering. Each is an important statement of the broad objectives of peace, development, and democracy, as well as a valuable road map to achieving those objectives. In combination, they suggest how states might use the UN more effectively over the long term to reduce the incidence and intensity of global violence.

An Agenda for Peace and the Supplement to An Agenda for Peace (published in 1993) emphasize the need to identify at the earliest possible moment the circumstances that could produce serious conflict and to try through diplomacy to remove the sources of danger.

13

While putting a high priority on such early attention to and engagement in potential crises, the basic report also discusses the necessity of dealing at later stages with peacemaking, peacekeeping, or peace building for the long run. It also stresses the need to address the deepest causes of conflict: economic despair, social injustice, and political oppression. An Agenda for Peace and the Supplement point the way for states to apply their considerable experience in managing interstate conflict to the pressing demands of the increasing numbers of wars within states.

An Agenda for Peace and the Supplement to An Agenda for Peace (published in 1993) emphasize the need to identify at the earliest possible moment the circumstances that could produce serious conflict and to try through diplomacy to remove the sources of danger.

13

While putting a high priority on such early attention to and engagement in potential crises, the basic report also discusses the necessity of dealing at later stages with peacemaking, peacekeeping, or peace building for the long run. It also stresses the need to address the deepest causes of conflict: economic despair, social injustice, and political oppression. An Agenda for Peace and the Supplement point the way for states to apply their considerable experience in managing interstate conflict to the pressing demands of the increasing numbers of wars within states.

An Agenda for Development recognizes that accelerated economic growth and widespread economic opportunity help generate positive social and technological transformations. 14 Economic growth should be pursued to provide employment, educational opportunities, and improved living standards for ever wider segments of the population. Traditional approaches to development that have given little regard to the political systems of developing countries have fallen into disfavor, and experts now generally agree that political progress toward representative government and economic progress toward market mechanisms with provisions for a social safety net are inextricably linked. It is also best to consider emergency relief and development jointly. An Agenda for Development helps channel the now-considerable interest that exists in rethinking and strengthening the UN's role in facilitating sustainable development.

An Agenda for Democratization makes clear that the UN can, when called upon, play a useful role in helping states establish and solidify a hold on democracy. 15 The right of the governed to a say in how they are governed has gained greater currency around the world as states have shed totalitarian pasts and as existing democracies cope with the burgeoning—and perhaps previously disregarded—needs of all citizens. Many models of democracy exist as do many paths to that end. UN action to promote democratic practices rests on the principles outlined in three core documents; the UN Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. Today, the UN, together with its member states, offers a wide range of assistance to help build the political culture necessary to sustain democratic practices.

The International Financial Institutions

Although many people may have forgotten it, the international financial institutions (IFIs) created at Bretton Woods—led by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—are part of the UN system. These institutions remained aloof from the UN and its other agencies during the Cold War, but today, together with regional financial institutions, the Bank and the IMF have a major interest and role to play in helping to prevent or cope with mass violence. Peace agreements need to be strengthened with economic development, and the Bank and the IMF have begun to focus on reconstruction to help prevent violence from reemerging.

The leverage of the IFIs could be used even more widely to provide incentives for cooperation in tense regions. Investment may act as a restraint on the causes of violence, and conditional assistance might be used to show that loans and grants are available to those who cooperate with their neighbors. In fact, the IFIs have experimented as far back as the 1950s with programs to demonstrate that economic growth could be achieved only through intergroup or regional cooperation. Moreover, with large investments in many conflict-prone countries, the Bank and the IMF have become concerned with both the need for good governance and the dangers of instability and violence. In 1997, for example, the World Bank signaled a major shift in its willingness to address issues of governance by devoting its annual flagship publication, World Development Report, to the theme "The State in a Changing World." But before these organizations can be more truly effective, they must also become more sensitive to local conditions, acquire and develop the necessary staff for dealing with critical social and political issues, and be more responsible for the advice they give (see Box 6.5). 16

|

The Commission believes that governments should encourage the World Bank and the IMF to establish better cooperation with the UN's political bodies so that economic inducements can play a more central role in early prevention and in postconflict reconstruction. 17

Every major regional arrangement, or organization, draws its legitimacy, in part, from the principles of the UN Charter. 18 Regional organizations are linked to the UN, not least because most UN member states are also members of regional organizations. Chapter VIII of the UN Charter urges regional solutions to regional problems, and nearly all of the major regional organizations cite the Charter in their own framing documents. These organizations vary in size, mandate, and effectiveness, but all represent ways in which states have tried to pool their strengths and share burdens. 19

Regional organizations have important limitations. They may not be strong enough on their own to counter the intentions or actions of a dominant state. Even if they are strong enough, regional organizations may not always be the most appropriate forum through which states should engage in or mediate an incipient conflict because of the competing goals of their member states or the suspicions of those in conflict. Nonetheless, if these organizations are inert or powerless in the face of imminent conflict, their functions as regional forums for dialogue, confidence building, and economic coordination will also be eroded. The potential of regional mechanisms for conflict prevention deserves renewed attention in the next decade.

Regional organizations, in all their diversity, can be divided into three groups: 1) security organizations of varying degrees of formality, such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the Organization of American States, the Organization of African Unity, the Western European Union, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Regional Forum; 2) economic organizations, again, of varying degrees of formality, such as the European Union, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation group, the North American Free Trade Agreement, the Mercado Común del Sur (MERCOSUR), and the Gulf Cooperation Council; and 3) general dialogue groups or political/cultural associations, such as the Commonwealth, La Francophonie, the Nonaligned Movement, the Organization of the Islamic Conference, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Appendix 2 lists selected regional organizations with brief discussions of their conflict prevention activities).

Security Organizations

Regional security organizations have some distinct advantages. 20 They are well situated to maintain a careful watch on circumstances and respond early and discreetly when trouble threatens. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), for example, has evolved increasingly active prevention mechanisms over the past several years (see Box 6.6). In Europe the Office of the High Commissioner on National Minorities has played an important role in resolving conflicts, often involving minority rights, before they turn violent.

|

Economic Organizations

The connections that underpin the global economy make regional economic organizations potentially important vehicles for harnessing states' prevention efforts. A number of examples in which the EU has become active have already been discussed. In addition, the April 1996 near-coup in Paraguay demonstrated that through creative preventive diplomacy, neighboring states can avert a downward spiral into violent conflict. When General Lino Oviedo tried to force President Juan Carlos Wasmosy to step down, Argentina and Brazil stepped in, threatening to expel Paraguay from MERCOSUR. Their dominant economic status in the region and influence on Paraguayan business gave Buenos Aires and Brasilia considerable leverage that they translated into immediate and effective preventive action. 21

Dialogue and Cooperation Groups

There are, of course, other regional and subregional organizations and partnerships through which states pursue common interests—in addition to the OSCE, the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC), the Gulf Cooperation Council, the Black Sea Economic Cooperation zone, and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) are examples of the increasing tendency of states to pursue common interests regionally in ways that complement their bilateral strategies.

Such efforts to promote cooperation, dialogue, and confidence building are, in many cases, still in the early stages. The histories of these organizations reflect a continual process of adapting to regional and global exigencies. Today, the greatest of these exigencies is violent conflict within the borders of states. No region is unaffected by this phenomenon. If regional organizations are to be helpful in coping with these changing circumstances, member states must be prepared to commit the resources and demonstrate the political will necessary to ensure that the regional efforts succeed.

The Commission believes that regional arrangements can be greatly strengthened for preventive purposes. They should establish means, linked to the UN, to monitor circumstances of incipient violence within the regions. They should develop a repertoire of diplomatic, political, and economic measures for regional use to help prevent dangerous circumstances from coalescing and exploding into violence. Such a repertoire would include developing ways to provide advance warning to organization members and marshaling regional support, including the necessary logistics, command and control, and other support functions for more assertive efforts authorized by the UN.

Notes

*: As noted in the prologue, Commission member Sahabzada Yaqub-Khan dissents from the Commission's view on Security Council reform. In his opinion, the additional permanent members would multiply, not diminish, the anomalies inherent in the structure of the Security Council. While the concept of regional rotation for additional permanent seats offers prospects of a compromise, it would be essential to have agreed global and regional criteria for rotation. In the absence of an international consensus on expansion in the permanent category, the expansion should be confined to nonpermanent members only. Back.

Note 1: Jesse Helms, "Saving the U.N.," Foreign Affairs 75, No. 5 (September/October 1996), pp. 2-7; James Holtje, Divided It Stands: Can the United Nations Work? (Atlanta, GA: Turner Publishing, Inc., 1995); Peter Wilenski, "The Structure of the UN in the Post-Cold War Period," in United Nations, Divided World: The UN's Roles In International Relations, eds. Adam Roberts and Benedict Kingsbury (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), pp. 437-467. Back.

Note 2: For an insightful examination of many of the United Nations' early efforts and innovations in peace and security operations, as examined through the life of United Nations diplomat Ralph Bunche, see Brian Urquhart, Ralph Bunche: An American Life (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1993). See also William J. Durch, ed., The Evolution of UN Peacekeeping: Case Studies and Comparative Analysis (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1993); United Nations, The Blue Helmets: A Review of United Nations Peace-keeping (New York: United Nations Department of Public Information, 1996). Back.

Note 3: The United Nations undertakes a number of tasks in addition to its more publicized work in areas such as peace and security, development, and human rights. Table N.2 identifies many of these fields and corresponding United Nations agencies. A Council on Foreign Relations study highlighted many of these roles as they relate to the U.S. national interest in an effective United Nations. See American National Interest and the United Nations: Statement and Report of an Independent Task Force (New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 1996).

|

Note 4: United Nations Childrens Fund, State of the World's Children 1996 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996). Back.

Note 5: United States Mission to the United Nations, "Global Humanitarian Emergencies 1996" (New York: February 1996), pp. 3-4; U.S. Committee for Refugees, World Refugee Survey 1997 (Washington, DC: Immigration and Refugee Services of America, 1997), pp. 5-6; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, The State of the World's Refugees 1995 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 255; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, "UNHCR by Numbers 1996" (Geneva: UNHCR Public Information Section, July 1996), p. 12. Back.

Note 6: For varying perspectives on the role of the United Nations secretary-general, see Thomas E. Boudreau, Sheathing the Sword: The U.N. Secretary-General and the Prevention of International Conflict (New York: Greenwood Press, 1991); Boutros Boutros-Ghali, "Challenges of Preventive Diplomacy: The Role of the United Nations and Its Secretary-General," in Preventive Diplomacy: Stopping Wars Before They Start, ed. Kevin M. Cahill (New York: Basic Books, 1996), pp. 16-32; Thomas M. Franck and Georg Nolte, "The Good Offices Function of the UN Secretary-General," in The UN and International Security after the Cold War: The UN's Roles in International Relations, eds. A. Roberts and B. Kingsbury (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), pp. 143-182; James Holtje, Divided It Stands: Can the United Nations Work? (Atlanta: Turner Publishing, Inc., 1995), pp. 97-124; Giandomenico Picco, "The UN and the Use of Force: Leave the Secretary-General Out of It," Foreign Affairs 73, No. 5 (September/October 1994), pp. 14-18; Brian Urquhart, "The Role of the Secretary-General," in U.S. Foreign Policy and the United Nations System, eds. Charles William Maynes and Richard S. Williamson (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996), pp. 212-228. Back.

Note 7: David Owen, Balkan Odyssey (London: Victor Gollancz, 1995), see especially pp. 354-355; Peter James Spielmann, "U.N. Chief Considers Reconvening Peace Talks on Bosnia," Associated Press, May 28, 1993. Back.

Note 8: See Olara Otunnu, "The Peace-and-Security Agenda of the United Nations: From a Crossroads into the Next Century," in Peacemaking and Peacekeeping for the Next Century, report of the 25th Vienna Seminar cosponsored by the Government of Austria and the International Peace Academy, March 2-4, 1995 (New York: International Peace Academy, 1995), pp. 66-82. Back.

Note 9: Boutros Boutros-Ghali, An Agenda for Peace, 2nd ed. (New York: United Nations, 1995), p. 44. Back.

Note 10: Commission on Global Governance, Our Global Neighborhood (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 71. Back.

Note 11: Kofi Annan, Renewing the United Nations: A Programme for Reform (New York: United Nations, 1997), para. 110. Back.

Note 12: Ibid., see especially para. 67, 76-79, 111-116, 180-184, 198. Prevention is an element of several other areas of interest in the secretary-general's report, including: drug control, crime prevention, and counterterrorism, para. 143-145; improving UN coordination with civil society, para. 207-216; and general managerial reform to streamline UN operations to eliminate duplication and enhance cooperation and information sharing, Annex. Back.

Note 13: Boutros Boutros-Ghali, An Agenda for Peace, 2nd ed. (New York: United Nations, 1995). Back.

Note 14: Boutros Boutros-Ghali, An Agenda for Development (New York: United Nations, 1995). Back.

Note 15: Boutros Boutros-Ghali, An Agenda for Democratization (New York: United Nations, 1996). Back.

Note 16: See John Stremlau and Francisco Sagasti, Preventing Deadly Conflict: Does the World Bank Have a Role? (Washington, DC: Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict, forthcoming). The only international financial institution that has a mandate to support the internal political development of borrowing states is the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. See Melanie H. Stein, "Conflict Prevention in Transition Economies: A Role for the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development?" in Preventing Conflict in the Post-Communist World: Mobilizing International and Regional Organizations, eds. Abram Chayes and Antonia Handler Chayes (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 1996), pp. 339-378. Back.

Note 17: In his report to the General Assembly, Secretary-General Kofi Annan has recommended that a commission be established to study the need for fundamental change in the system at large. The Commission supports this call for the reasons outlined herein. Kofi Annan, op. cit., para. 89. Back.

Note 18: This section draws on a study prepared for the Commission by Connie Peck of the United Nations Institute for Training and Research, Sustainable Peace: The Role of the UN and Regional Organizations in Preventing Conflict (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1997). For further discussions on the relative strengths and weaknesses of regional organizations, see Charles Van der Donckt, Looking Forward by Looking Back: A Pragmatic Look at Conflict and the Regional Option, Policy Staff Paper No. 95/01, Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, September 1995; Ruth Wedgwood, "Regional and Subregional Organizations in International Conflict Management," in Managing Global Chaos: Sources of and Responses to International Conflict, eds. Chester A. Crocker and Fen Osler Hampson, with Pamela Aall (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1996), pp. 275-285. Back.

Note 19: The charters and treaties of many regional organizations explicitly acknowledge the importance of the United Nations and the primacy of the principles embodied in the UN Charter. The Organization of African Unity Charter (1963) states that one of the group's purposes is "to promote international cooperation, having due regard to the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights." The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) highlights the necessity of "adherence to the principles of the United Nations Charter" in the Bangkok Declaration (1967) and the Singapore Declaration of 1992 affirms ASEAN's "commitment to the centrality of the UN role in the maintenance of international peace and security as well as promoting cooperation for socioeconomic development." The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe in the Charter of Paris for a New Europe (1990) reaffirms the "commitment to the principles and purposes of the United Nations as enshrined in the Charter and condemn[s] all violations of these principles. We recognize with satisfaction the growing role of the United Nations in world affairs and its increasing effectiveness...." The European Union's Maastricht Treaty seeks "to preserve peace and strengthen international security, in accordance with the principles of the United Nations Charter." The oldest of the regional organizations, the Organization of American States, resolves "to persevere in the noble undertaking that humanity has conferred upon the United Nations, whose principles and purposes they solemnly reaffirm." Even the Treaty of Washington that led to the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) takes full cognizance of the UN Charter and its principles as well as the rights and responsibilities of the Security Council and member states of the UN. Back.

Note 20: Ruth Wedgwood, "Regional and Subregional Organizations in International Conflict Management," in Managing Global Chaos: Sources of and Responses to International Conflict, eds. Chester A. Crocker and Fen Osler Hampson, with Pamela Aall (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1996), pp. 276-278. Back.

Note 21: Richard Feinberg, "The Coup That Wasn't," Washington Post, April 30, 1996, p. A13. Back.