|

|

|

|

Final Report With Executive Summary

Carnegie Corporation of New York

1997

5. Preventing Deadly Conflict

The Responsibility of States, Leaders, and Civil Society

Widespread deadly conflict threatens global stability by eroding the rules and norms of behavior that states have sought to establish. Rampant human rights abuses are often the prelude to violence. They reflect a breakdown in the rule of law, and if they are allowed to continue unchecked, the result will be weakened confidence in states' commitment to the protection of human rights, democratic governance, and international treaties. Moreover, the lack of a response—particularly by states that have an obvious capacity to act—will encourage a climate of lawlessness in which disaffected peoples or opposing factions will increasingly take matters into their own hands. The effort to help avert deadly conflict is thus not only a matter of humanitarian obligation, but also of enlightened self-interest.

Major preventive action remains the responsibility of states, and especially their leaders. States must decide whether they do nothing, act alone, act in cooperation with other governments, work through international organizations, or work with elements of the private sector. It should be an accepted principle that those with the greatest capacity to act have the greatest responsibility to act.

The Commission is of the strong view that the leaders, governments, and people closest to potentially violent situations bear the primary responsibility for taking preventive action. They stand to lose most, of course, if their efforts do not succeed. The Commission believes that the best approach to prevention is one that emphasizes local solutions to local problems where possible, and new divisions of labor—involving governments and the private sector—based on comparative advantage and augmented as necessary by help from outside. The array of those who have a useful preventive role to play should extend beyond governments and intergovernmental organizations to include the private sector with its vast expertise and resources. The Commission urges combining governmental and nongovernmental efforts.

Governments ignore violent conflict, wherever it occurs, at great risk. The bills for postconflict reconstruction and economic renewal inevitably come due, and there are only a limited number of states willing and able to pay them, mainly the industrialized democracies. The Commission believes that these states should engage more constructively and comprehensively to help prevent deadly conflict, guided by international standards and their common respect for human rights, the dignity of the individual, and the protection of minorities. They could, for example, act within the UN system—together with other like-minded states—to establish and reinforce norms of fairness and nonviolent conflict resolution. As the previous chapter argued, democratic practice is linked to the prevention of deadly conflict.

The Commission recognizes that sometimes the industrialized democracies promote policies abroad that contradict their democratic values at home and thereby contribute to deadly conflict. Moreover, some democracies have been reluctant to meet their responsibilities in the United Nations and elsewhere, weakening a potentially powerful force for the international community in preventing mass violence.

At a minimum, these states must do what they can to ensure that their own development and economic expansion do not engender volatile circumstances elsewhere. Further, they should develop mechanisms to anticipate violent conflict and to formulate coordinated responses. For example, the agenda of any G-8 meeting should include a discussion of developing conflicts and ways members can help resolve them before they become violent. Leaders should make prevention a high priority on the agenda of every head of state/government summit meeting and on the agenda of all foreign and defense ministerials. They should use all of their relevant meetings to discuss circumstances of incipient violence and to formulate strategies to link bilateral, regional, and UN efforts to prevent actual outbreaks. Their summit communiques should highlight leaders' awareness of and plans for dealing with the developing crises.

Sometimes those involved in conflict ask for outside help early, but all too often they wait until long after it has become clear that they cannot possibly sort out their problems or deal with the consequences on their own. As violence escalates, rational and moderate behavior becomes increasingly difficult. The parties become more and more reluctant to resort to nonviolent dispute resolution mechanisms. In such situations, those more remote from the conflict may help to convey a realistic picture of the advantages of peaceful solutions and the disadvantages of violence, and thus persuade the combatants at last to turn away from violence (see Box 5.1). This kind of help can come from other states, intergovernmental organizations, and the nongovernmental or private sectors. Governments should refine this capacity to identify and track circumstances of potential violence—to develop reliable links between the private sector, where warning is often most apparent, and senior government decision makers with the authority to act in the face of such warning, and, in turn, to international organizations for coordinated action.

|

Increasingly, many states—often not the major powers but smaller states that are also practiced in the art of what can be achieved through coalition building and selectively focused efforts—have begun to respond to the rising tide of worldwide violence. Certain countries—the Nordics, for example—have a distinguished record of deep commitment and action in helping moderate the effects of violence around the world. Norway has organized an innovative governmental-private sector approach to international crisis that can be mobilized in short order to great effect (see Box 5.2). This so-called Norwegian Model involves close cooperation between all relevant government departments and NGOs, and a well-informed and supportive public that can yield hundreds of volunteers on short notice to participate in international humanitarian and peace initiatives. 1 The Swedish Foreign Ministry instructs its missions to relay information on human rights practices, which can be used to assess the risk of conflict. 2 This information would be used not only to strengthen the ability of Swedish institutions to respond more rapidly and effectively to emerging conflicts, but also to aid in early warning and response efforts at the international level.

|

Canada, the Netherlands, and Ireland also have long traditions of humanitarian engagement. Canadian and Dutch studies have explored ways to make a rapid reaction capability available for the United Nations, and the results of these efforts have helped advance the debate over this issue beyond theoretical argument to practical organization (see pages 65-67 for further discussion). 3 Ireland has sent humanitarian aid workers throughout Africa, including to some of the most difficult and dangerous areas, such as Somalia, Ethiopia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (Zaire).

In the United States, the Department of State established the Secretary's Preventive Action Initiative in 1994 as an internal mechanism to improve political and diplomatic anticipation of violence, and the Department of State's National Foreign Affairs Training Center has added conflict prevention training to its curriculum. The Department of Defense has for several years pursued a program of "preventive defense," tying military and nonmilitary programs together in an effort to coordinate and broaden American efforts to prevent deadly conflict. 4 In Great Britain, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office has taken steps to create a capacity to anticipate and respond to incipient violence. Australia played a conspicuous role in the Cambodian peace process, in advancing the Chemical Weapons Convention and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, and—prominently through the Canberra Commission—in making the case for the ultimate elimination of nuclear weapons.

In addition to these examples, a number of governments are engaged in a major cooperative effort, as this report is written, to institute a worldwide ban on the production, stockpiling, distribution, and use of land mines. The Commission strongly endorses this effort. 5

As states and leaders become more attentive to prevention, new policies should build on such steps and combine more effectively governmental and nongovernmental efforts. The goal is a system of conflict prevention that takes into account the strengths, resources, and limitations of each component of the system.

Pivotal Institutions of Civil Society

The record of unprecedented slaughter in the twentieth century suggests that the traditional system, if it can be called a system, in which governments and intergovernmental organizations take an exclusive role in efforts to cope with problems of conflict, mass violence, war, and peace, has not worked well. It is, therefore, necessary to look to relatively new groups to augment efforts in this vital task.

It bears repeating that governments—especially those closest to a conflict—have the greatest responsibility for preventive action. The following sections discuss the capacity for preventive action that resides in the private and nongovernmental sectors, and the following chapter discusses the preventive capacities of intergovernmental organizations. The Commission believes that much of what these various agencies and organizations can do to help prevent deadly conflict will be aided or impeded by the actions of states.

How can the contributions of various elements of the private sector—NGOs, religious leaders and organizations, the educational and scientific communities, business, and the media—contribute to the prevention of conflict? How can these various groups be strengthened in societies where violence threatens? This latter question becomes especially important in circumstances where repressive regimes stifle civil society and undermine the development of local capacities for problem solving. It is important to identify elements of civil society that can be used to reduce hatred and violence and to encourage attitudes of concern, social responsibility, and mutual aid within and between groups. Labor unions, for example, have in many circumstances helped facilitate citizen participation in peaceful democratic change. 6 Indeed, in South Africa the broader role of civil society represents an example of how this can work on a nationwide scale (see Box 5.3).

|

Many elements in the private sector around the world are dedicated to helping prevent deadly conflict and have declared a public commitment to the well-being of humanity in their various activities. They have raised considerable sums of money on the basis of this commitment, bringing them many opportunities but also great responsibilities.

Nongovernmental Organizations

Virtually every conflict in the world today has had some form of international response and presence—whether humanitarian, diplomatic, or other—and much of that presence comes from the nongovernmental community. Performing a wide variety of humanitarian, medical, educational, and other relief and development functions, nongovernmental organizations are deeply engaged in the world's conflicts, and are now frequently significant participants in most efforts to manage and resolve deadly conflict. Indeed, NGO workers are often exposed to the same dangers and hardships as any uniformed soldier.

Nongovernmental organizations, an institutional expression of civil society, are important to the political health of virtually all countries, and their current and potential contributions to the prevention of deadly conflict, especially mass violence within states, is rapidly becoming one of the hallmarks of the post-Cold War era. 7

As pillars of any thriving society, NGOs at their best provide a vast array of human services unmatched by either government or the market, and are the self-designated advocates for action on virtually all matters of public concern. 8 The rapid spread of information technology, market-driven economic interdependence, and easier and less expensive ways of communicating within and among states have allowed many NGOs—through their worldwide operations—to become key global transmission belts for ideas, financial resources, and technical assistance. In difficult economic and political transitions, the organizations of civil society are of crucial importance in alleviating the dangers of mass violence.

NGOs vary in size and mandate. They range from large global organizations, such as Oxfam, that operate in scores of countries with budgets in the hundreds of millions of dollars, to much smaller NGOs, such as the Nairobi Peace Initiative in Kenya, that focus only on one country or on one type of problem (see Box 5.4).

|

An expanding array of NGOs work at the frontiers of building the political foundations and international arrangements for the long-term prevention of conflict. They work on problems of the environment, arms control, world health, and a host of other global issues. Three broad categories of NGOs offer especially important potential contributions to the prevention of deadly conflict: human rights and other advocacy groups; humanitarian and development organizations; and the small but growing number of "Track Two" groups that help open the way to more formal internal or international peace processes.

Human rights, Track Two, and grassroots development organizations all provide early warning of rising local tension and help open or protect the necessary political space between groups and the government that can allow local leaders to settle differences peacefully. Nongovernmental humanitarian agencies have great flexibility and access in responding to the needs of victims (especially the internally displaced) during complex emergencies. Development and prodemocracy groups have become vital to effecting peaceful transitions from authoritarian rule to more open societies and, in circumstances of violent conflict, in helping to make peace processes irreversible during the difficult transitions to reconstruction and national reconciliation. The work of international NGOs and their connection to each other and to indigenous organizations throughout the world reinforce a sense of common interest and common purpose, as well as the political will to support collective measures for preventive action.

Many NGOs have deep knowledge of regional and local issues, cultures, and relationships, and an ability to function in adverse circumstances even, or perhaps especially, where governments cannot. Moreover, nongovernmental relief organizations often have legitimacy and operational access that do not raise concerns about sovereignty, as government activities sometimes do.

Some NGOs have an explicit focus on conflict prevention and resolution. They may: monitor conflicts and provide early warning and insight into a particular conflict; convene the adversarial parties (providing a neutral forum); pave the way for mediation and undertake mediation; carry out education and training for conflict resolution, building an indigenous capacity for coping with ongoing conflicts; help to strengthen institutions for conflict resolution; foster development of the rule of law; help to establish a free press with responsible reporting on conflict; assist in planning and implementing elections; and provide technical assistance on democratic arrangements that reduce the likelihood of violence in divided societies.

With conflicts raging in every part of the globe, the NGO community has become overstretched by incessant demands for engagement and resources. 9 To meet these demands, NGOs must improve coordination with other NGOs and with intergovernmental organizations and governments to reduce unnecessary redundancies among and within their own operations. Indeed, some of the global NGOs have begun to sharpen their focus on specific aspects of humanitarian relief. For example, Oxfam UK and Ireland focuses on water and sanitation, CARE on logistical operations, and Catholic Relief Services on food distribution. 10

The leadership of the major global humanitarian NGOs should agree to meet regularly—at a minimum on an annual basis—to share information, reduce unnecessary redundancies, and promote shared norms of engagement in crises. This collaboration should lead directly to the wider nongovernmental commitment to network with indigenous NGOs in regions of potential crisis, human rights groups, humanitarian organizations, development organizations, and those involved in Track Two efforts to help prevent and resolve conflict.

Because they have had to work more closely with intergovernmental organizations and with governments—particularly with the military—in dangerous, uncertain circumstances, NGOs have had to broaden their dialogue with these partners to reduce the potential for dysfunctional relationships that can further complicate already extremely complex and difficult operations. One way in which the process of information sharing can be improved is through the establishment of conflict forums (e.g., the Great Lakes Policy Forum in the United States) to exchange information in a timely fashion and craft creative approaches to nonviolent problem solving. The Commission also recommends that the secretary-general of the UN follow through with his aim of strengthening NGO links to UN deliberation by establishing a means whereby NGOs and other agencies of civil society would bring relevant matters to the attention of competent organs of the United Nations. Other ideas to strengthen the UN for prevention are presented in chapter 6.

Unlike governments, NGOs cannot compel belligerents to respect human rights or cease violent attacks. Whatever their niche, NGOs must function with cultural and political sensitivity or risk accusations of paternalism, or worse, political partiality or corruption. To avoid any sense that they might become tools or pawns in the hands of conflicting factions, NGOs have been working to establish their own code of ethics. 11

The Commission strongly endorses the important role of NGOs in helping to prevent deadly conflict. NGOs have the flexibility, expertise, and commitment to respond rapidly to early signs of trouble. They witness and give voice to the unfolding drama, and they provide essential services and aid. Not least, they inform and educate the public both at the national level and worldwide on the horrors of deadly conflict and thus help mobilize opinion and action.

Religious Leaders and Institutions

Five factors give religious leaders and institutions from the grass roots to the transnational level a comparative advantage for dealing with conflict situations: 1) a clear message that resonates with their followers; 2) a long-standing and pervasive presence on the ground; 3) a well-developed infrastructure that often includes a sophisticated communications network connecting local, national, and international offices; 4) a legitimacy for speaking out on crisis issues; and 5) a traditional orientation to peace and goodwill. Because of these advantages, religious institutions have on occasion played a reconciling role by inhibiting violence, lessening tensions, and contributing decisively to the resolution of conflict (see Box 5.5).

|

A number of religious groups are deeply committed to building bridges between factions in conflict. Since 1965, the Corrymeela Community, one of a number of groups engaged in religious reconciliation in Northern Ireland, has attempted to provide forums for interaction in the communities to dispel ignorance, prejudice, and fear and to promote mutual respect, trust, and cooperation. In the former Yugoslavia, a permanent Inter-Religious Council has been created by the leaders of four religious communities—Muslim, Jewish, Serb Orthodox, and Roman Catholic—to promote religious cooperation in Bosnia and Herzegovina by identifying and expressing their common concerns independent of politics. 12

Religious advocacy is particularly effective when it is broadly inclusive of many

faiths. A number of dialogues between religions already exist—the World Council of Churches as well as forums for Jewish/Christian dialogue, Christian/Muslim dialogue, and others—to provide opportunities for important interfaith exchanges on key public policy issues.

Religious advocacy is particularly effective when it is broadly inclusive of many

faiths. A number of dialogues between religions already exist—the World Council of Churches as well as forums for Jewish/Christian dialogue, Christian/Muslim dialogue, and others—to provide opportunities for important interfaith exchanges on key public policy issues.

When a religious community is perceived as neutral and apolitical, it may qualify as an honest broker and neutral mediator. The good offices of religious groups, active in most settings through impressive works of charity and social relief, often lend legitimacy to negotiations. This role was officially recognized in the Ottoman Empire's millet system, for example, where the religious leaders of Judaism and several Christian churches were entrusted with arbitrating conflicts among their coreligionists.

The Community of Sant'Egidio played an essential role in brokering the settlement of the Mozambique civil war. 13 It also brokered an agreement on education in Serbia's Kosovo province between Belgrade and the local ethnic Albanian leadership. For more than a year, Sant'Egidio hosted secret peace talks in Rome for the warring factions in Burundi that led to the formal intergovernmental negotiations, known as the Arusha process, chaired by former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere. The All Africa Conference of Churches has also become diplomatically active, notably in the 1997 conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo, by advocating peaceful political change, and respect for the rule of law and human rights throughout Central Africa. 14

Religious groups are simultaneously local, national, and international entities. They are on the ground, but also part of an extensive and constantly growing transnational network. Drawing on this distinctive advantage, some churches in the former Soviet Bloc kept national pride and religious consciousness alive during the Communist period by maintaining important links to the West through their ecclesiastical and ecumenical contacts. Churches in East Germany, for example, were probably crucial in averting mass violence in the transition away from dictatorial rule (see Box 5.6). Similar functions have been served during the past decade in South Africa (highlighted by the remarkable leadership of Desmond Tutu) and, as noted, the Philippines.

|

There is a need for increased interfaith dialogue, so that religious leaders can discover their common ground. The Commission believes that religious leaders and institutions should be called upon to undertake a worldwide effort to foster respect for diversity and to promote ways to avoid violence. 15 They should discuss as a priority matter, during any interfaith and intrafaith gathering, ways to play constructive and mutually supporting roles to help prevent the emergence of violence. They should also take more assertive measures to censure coreligionists who promote violence or give religious justification for violence. They can do so, in part, through worldwide promulgation of norms for tolerance to guide their faithful (see Box 5.7 for one prominent example).

|

The Scientific Community

One of the great challenges for scientists and the wider scholarly community in the coming decades will be to undertake a much broader and deeper effort to understand the nature and sources of human conflict, and above all to develop effective ways of resolving conflicts before they turn violent.

The scientific community is the closest approximation we now have to a truly international community, sharing certain fundamental interests, values, standards, and a spirit of inquiry about the nature of matter, life, behavior, and the universe. This shared quest for understanding has overcome the distorting effects of national boundaries, inherent prejudices, imposed ethnocentrism, and barriers to the free exchange of information and ideas.

Drawn together more than ever by recent advances in telecommunications, these attributes of the scientific community have been put to work in recent decades in efforts to prevent war and especially to reduce the nuclear danger. The community draws on a scientific base of accurate information, sound principles, and well-documented techniques. It acts flexibly, exploring novel or neglected paths toward conflict resolution, and it builds relationships among well-informed people who can make a difference in attitudes and in problem solving and who are taken seriously by governments.

The scientific community first and foremost provides understanding, insight, and stimulating ways of analyzing important problems. It can and must do so with regard to deadly conflict. Through their institutions and organizations, scientists can strengthen research in a variety of areas, for example, the biology and psychology of aggressive behavior, child development, intergroup relations, prejudice and ethnocentrism, the origins of wars and conditions under which they end, weapons development and arms control, and innovative pedagogical approaches to mutual accommodation and conflict resolution. Other research priorities include exploring ways to use the Internet and other communications innovations to defuse tensions, demystify adversaries, and convey information to strengthen moderate elements. The scientific community should also establish links among all sides of a conflict to determine whether any aspects of a crisis are amenable to technical solutions and to reduce the risk that these issues could provide flash points for violence.

During the decades of the Cold War, the scientific community sought ways to reduce the number of nuclear weapons and especially their capacity for a first strike. It also worked to decrease the chance of accidental or inadvertent nuclear war, to safeguard against unauthorized launch and serious miscalculation, and to improve the relations between the superpowers, partly through cooperative efforts in key fields bearing on the health and safety of humanity. One of the reasons that scientists were able to exercise influence in Cold War affairs certainly stemmed from their role in creating the technology of the nuclear age. For their part, scientists believed they had a heavy responsibility to think about the implications of the devastating weapons they had created.

A prominent example of international scientific cooperation during the among well-informed pCold War was the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1995. In the mid-1950s, Albert Einstein and Bertrand Russell issued a manifesto calling on the world's scientists to devise ways to avert the disaster threatened by the products of their science (their first meeting took place in Pugwash, Nova Scotia, in 1957). At that meeting, the participants found in scientific objectivity and in their common humanity the possible basis for solutions to the nuclear problem that could transcend national differences. After the initial meeting, a continuing series of informal discussions among the world's scientists yielded many recommendations to world governments. 16

The Cold War experience makes clear that there is an important role for the scientific and scholarly community in international conflict prevention. It has much to contribute, and governments and nongovernmental organizations, in turn, have much to learn.

All research-based knowledge of human conflict, the diversity of our species, and the paths to mutual accommodation are appropriate for education. Education is a force for reducing intergroup conflict by enlarging our social identifications beyond parochial ones in light of common human characteristics and superordinate goals—highly valued aspirations that can be achieved only by intergroup cooperation. We must seek a basis for fundamental human identification across a diversity of cultures in the face of manifest differences. We are a single, interdependent, meaningfully attached, worldwide species sharing a fragile planet. The give and take fostered within groups can be extended far beyond childhood, toward relations between adults and into larger units of organization, including international relations.

There is an extensive body of research on intergroup contact that bears on this question. For example, experiments have demonstrated that the extent of contact between groups that are negatively oriented toward one another is not the most important factor in achieving a more constructive orientation. What matters is whether the contact occurs under favorable conditions. If there is an aura of mutual suspicion, if the parties are highly competitive, if they are not supported by relevant authorities, or if contact occurs on the basis of very unequal status, then it is not likely to be helpful, whatever the amount of exposure. Contact under unfavorable conditions can stir up old tensions and reinforce stereotypes.

On the other hand, if there is friendly contact in the context of equal status, especially if such contact is supported by relevant authorities, if the contact is embedded in cooperative activity and fostered by a mutual aid ethic, then there is likely to be a strong positive outcome. Under these conditions, the more contact the better. Such contact is then associated with improved attitudes between previously suspicious or hostile groups, as well as with constructive changes in patterns of interaction between them. 17

Pivotal educational institutions such as the family, schools, community-based organizations, and the media have the power to shape attitudes and skills toward decent human relations—or toward hatred and violence. Such organizations can utilize the findings from research on intergroup relations and conflict resolution. 18 Much of what schools can accomplish is similar to what parents can do—employ positive discipline practices, teach the capacity for responsible decision making, foster cooperative learning procedures, and guide children in prosocial behavior outside the schools as well as in them. They can convey the fascination of other cultures, making understanding and respect a core attribute of their outlook on the world—including the capacity to interact effectively in the emerging global economy, a potentially powerful motivation in the world of the next century. They can use this knowledge to foster sympathetic interest across cultures, recognition of shared and valued goals, as well as a mutual aid ethic. 19 The process of developing school curricula to introduce students to the values of diversity and to break down stereotypes should be accelerated.

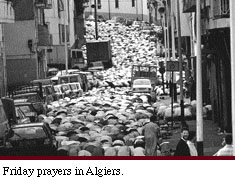

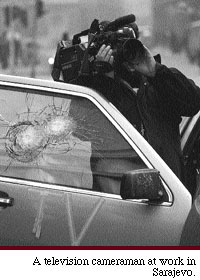

With so many post-Cold War conflicts instigated by harshly nationalist and sectarian leaders, the media's role in disseminating erroneous information or inflammatory propaganda has become an issue of great significance. Because these wars often occur in remote areas and have complicated histories, the international view of them will depend to a large extent on how international journalists present and explain the conflict. On the other hand, some of the deadliest conflicts, as in Sierra Leone, receive little mention in the global media.

A number of examples in the 1990s suggest that the impact of media reporting may generate political action. In Somalia, vivid images of a dead American soldier being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu were broadcast around the world and played a role in the precipitous American withdrawal from that country. In Bosnia, while many episodes of violence occurred over four years, those that were widely covered by the media, such as the marketplace bombing in Sarajevo in 1994, directly influenced responses from the United States, the European Union, and the UN. 20

If the linkage is as tight as these examples suggest, it raises the question of how the media should recast their own sense of responsibility when covering conflicts or crises. Whether or not the media can rightly be construed as independent entities, their influence as a whole is enormous, particularly in real time. Across the spectrum of activities, from worldwide broadcasts of violence and misery to the local hate radio that instigated killing in Rwanda and Bosnia, the media's interpretive representation of violent events has a wide and powerful impact. It is important to encourage the constructive use of the media to promote understanding, nonviolent problem solving, and decent intergroup relations, even though these issues often do not come under the heading of "breaking news."

A great challenge for the media is to report conflicts in ways that engender constructive public consideration of possibilities for avoiding violence. The media can stimulate new ideas and approaches to problems by involving independent experts in their presentations who can also help ensure factual, accurate reporting. The media should develop standards of conduct in crisis coverage that include giving adequate attention to serious efforts under way to defuse and resolve conflicts, even as they give full international exposure to the violence itself. An international press council, consisting largely of highly respected professional journalists, could be helpful in this regard, especially in monitoring and enforcing acceptable professional practices. The council could bring professional peer pressure on editors in conflict areas who might otherwise disseminate hate messages—especially if the council had a rapid reaction capability. There might be professional sanctions for promoting hate messages, such as cutting off access to international news programming and services. In addition, major networks should develop ways to expose publics to the circumstances and issues that could give rise to mass violence through regular public service programming that focuses on individual "hot spots." Such a service could be coproduced with international media collaborators and also made available to schools and other educational outlets. Models of professional standards for media in reporting on serious conflicts have recently been created and should be widely disseminated. 21

Television and radio have an unfulfilled potential for reducing tensions between countries or other disputants, and they can be used to demystify the adversary and improve

understanding. For example, the Voice of America (VOA), part of the United States Information Service, launched a Conflict Resolution Project in 1995. The project develops and produces special programs to introduce its worldwide audience to the principles and practices of conflict resolution. For this series, journalists move beyond hard news toward production of stories that explore local efforts to resolve problems, social relations, and individual and group efforts for peace. A core series of 24 documentary programs in several languages is adapted to the needs of specific audiences. It has included a lecture series on media and conflict prevention, a workbook for journalists reporting in emerging democracies, and broadcasting on conflict resolution. Activities have included journalist training in Angola and a daily radio show broadcast in the Kinyarwanda/Kirundi language aimed at Rwanda and Burundi.

22

Television and radio have an unfulfilled potential for reducing tensions between countries or other disputants, and they can be used to demystify the adversary and improve

understanding. For example, the Voice of America (VOA), part of the United States Information Service, launched a Conflict Resolution Project in 1995. The project develops and produces special programs to introduce its worldwide audience to the principles and practices of conflict resolution. For this series, journalists move beyond hard news toward production of stories that explore local efforts to resolve problems, social relations, and individual and group efforts for peace. A core series of 24 documentary programs in several languages is adapted to the needs of specific audiences. It has included a lecture series on media and conflict prevention, a workbook for journalists reporting in emerging democracies, and broadcasting on conflict resolution. Activities have included journalist training in Angola and a daily radio show broadcast in the Kinyarwanda/Kirundi language aimed at Rwanda and Burundi.

22

A Cold War example was provided by U.S.-Soviet "space bridge" programs—live, unedited discussion between citizens of the two countries made possible by communications satellites and simultaneous translation. Starting in 1983, U.S.-Soviet space bridges brought together American and Soviet citizens in an effort to overcome stereotypes, and they provided an opening to Gorbachev's policy of glasnost. Each space bridge program reached about 200 million people. Later, Internews's "Capital to Capital" program—broadcast simultaneously on U.S., Soviet, and East European television—linked members of Congress and the Supreme Soviet for uncensored debate on arms control, human rights, and the future of Europe.

Independent, pluralistic media can promote democracy by clarifying issues and helping the public to understand candidates. International election monitors should therefore observe media practices, such as candidate access, as well as the voting process itself. Mass media reporting on the possibilities for conflict resolution, and on the willingness and capacity of the international community to help, could become a useful support for nonviolent problem solving. Conflict areas need independent television and radio news channels broadcasting throughout the region. Radio can reach virtually everyone, everywhere. Independent radio was particularly effective during the UN operation in Cambodia. Radio UNTAC, as the UN's network was known, broadcast a variety of news and civic education programs to all regions of the country. The broadcasts were a vital tool for educating Cambodians about the UN's activities—particularly the electoral process established and administered by UNTAC—and for countering anti-UN propaganda. 23

The Business Community

International business has been criticized for insensitivity in matters of human rights, democracy, and conflict resolution. Yet the business community is beginning to recognize its interests and responsibilities in helping to prevent conditions that can lead to deadly conflict. Many businesses are in fact truly global in character, and violence or dangerously unstable circumstances will inevitably affect their interests (see Figure 5.1). Businesses should accelerate their work with local and national authorities in an effort to develop business practices that not only permit profitability but also contribute to community stability. This "risk reduction" approach to market development will help sensitize businesses to any potentially destabilizing violent social effects that new ventures may have, as well as reduce the premiums businesses may have to pay to insure their operations against loss in volatile areas.

|

|

Multinational corporations are under increasing pressure from consumers and shareholders to work toward economic, political, and social justice, and they have responded by developing codes of conduct for their business operations. These codes share several elements: 1) respect for human dignity and rights; 2) respect for the environment; 3) respect for stakeholders—customers, employees, shareholders, suppliers, and competitors; 4) respect for the communities in which businesses operate; and 5) maximizing value for the company. Among the corporations that have developed such codes are Levi Strauss & Company, Campbell Soup Company, and The Gap, Inc. Additionally, many companies now make corporate responsibility information available through their annual reports. The Body Shop, Ben & Jerry's, ARCO, and Ford Motor Company produce independent annual social and environmental progress reports.

The Commission believes that governments can make far greater use of business in conflict prevention. For example, governments might establish business advisory councils to draw more systematically on the knowledge of the business community and to receive their advice on the use of sanctions and inducements. With their understanding of countries in which they produce or sell their products, businesses can recognize early warning signs of danger and work with governments to reduce the likelihood of violent conflict. However, business engagement cannot be expected to substitute for governmental action.

The strength and influence of the business community give it the opportunity both to act independently and to put pressure on governments to seek an early resolution of emerging conflict (see Box 5.8). For this purpose it would be useful to reserve time at any major business gathering to discuss deadly conflict around the world and its consequences for international business.

|

The business community could also play a significant role in conflict prevention through industry's support of laboratory research in many parts of the world. The scientists and engineers who work in corporate laboratories have experience in cooperating with their peers across international boundaries, even in crisis situations. Their culture, like that of the scientific community in general, is one that relies heavily on international cooperation.

The People

Finally, what of ordinary people who may be the immediate victims of violence or citizens of countries that could prevent violence? Their choices are few and not easy to exercise. Those in conflict can, at considerable personal risk, refuse to support leaders bent on a violent course; those more removed can demand that their governments undertake preventive action and hold them accountable when they refuse. Their only real strength is in their numbers: in trade unions, community groups, and other organizations that make up civil society. The Solidarity movement in Poland is an example of this kind of citizen power (see Box 5.9). Women's movements are another potentially powerful force. Since the first International Women's Conference in Mexico City in 1995, women have been mobilizing internationally and pursuing their many shared interests throughout the world. 24

|

Mass movements, particularly nonviolent movements, have changed the course of history, most notably in India where Mohandas Gandhi led his countrymen in nonviolent resistance to British rule. Hundreds of millions were moved by the example of a simple man in homespun who preached tolerance and respect for the least powerful of India's peoples and full political participation for all. In South Africa, the support of the black majority for international sanctions and the broadly nonviolent movement to end apartheid helped bring the white government to the realization that the status quo could no longer be maintained. In the United States, the leadership of Martin Luther King, Jr., inspired whites and blacks in a massive movement for civil rights. The power of the people in the form of mass mobilization in the streets was critical in achieving the democratic revolution in the Philippines in 1986 and in Thailand in 1992.

Is it possible to harness the energy of the masses to help avert the outbreak of violence? Is it possible to turn people's energies away from violence and toward more constructive resolution of conflict? Would this require more leaders like Gandhi or Mandela or King? Would it require a new commitment by parents and schools to educate our children in conflict prevention? Following a discussion of the role that international organizations can play, this report concludes with a chapter on the possibilities for building a worldwide culture of prevention.

Notes

Note 1: Ian Smillie and Ian Filewod, "Norway," in Non-Governmental Organisations and Governments: Stakeholders for Development, eds. Ian Smillie and Henny Helmich (Paris: OECD, 1993), pp. 215-232. Back.

Note 2: Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Preventing Violent Conflict: A Study (Stockholm: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1997), pp. 44-45. See also a recent article by Sweden's Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs for reflections on enhancing the UN's conflict prevention efforts: Jan Eliasson, "Establishing Trust in the Healer: Preventive Diplomacy and the Future of the United Nations," in Preventive Diplomacy: Stopping Wars Before They Start, ed. Kevin M. Cahill (New York: Basic Books and The Center for International Health Cooperation, 1996), pp. 318-343. Back.

Note 3: See Government of Canada, Towards a Rapid Reaction Capability for the United Nations, Report of the Government of Canada, September 1995; Dick A. Leurdijk, ed., A UN Rapid Deployment Brigade: Strengthening the Capacity for Quick Response (The Hague: Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael, 1995). Back.

Note 4: The preventive defense strategy developed by former U.S. Secretary of Defense William J. Perry centers on preventing conflict through U.S. engagement with allies and former enemies. Preventive defense seeks to halt the outbreak of conflict by turning adversaries into partners. Taking the Marshall Plan as its model, preventive defense is based on enhancing alliances and bilateral relationships, regional confidence building, constructive engagement, and nonproliferation of weapons of mass destruction. Initiatives such as the Cooperative Threat Reduction (Nunn-Lugar) program, the US-Russian Commission on Economic and Technological Cooperation (Gore-Chernomyrdin), Partnership for Peace (PFP), the NATO-Russian Charter (the Founding Act), and International Military Education and Training programs with centers in Germany and Hawaii are central to promoting stability and monitoring developments in a number of regions on the brink of conflict. For example, Partnership for Peace's military exercises and civilian meetings have created an expanding network of security relationships in Europe, building confidence, increasing transparency, and reducing tensions. Likewise, maintaining strong ties with partners in Asia and engaging with China, India, Pakistan, and others to increase understanding and avert crises are vital elements of preventive defense. Similar efforts are under way in Africa and the Americas.

Continuing the focus on prevention, Secretary of Defense William Cohen emphasizes the importance of U.S. global engagement to shape the international security environment. This strategy is based on the view that maintaining order and stability requires strong U.S. leadership to promote peace, prosperity, and democracy, and for this purpose military-to-military cooperation and nonproliferation programs remain a high priority for the Department of Defense. See William S. Cohen, The Report of the Quadrennial Defense Review (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1997); William S. Cohen, Annual Report to the President and Congress (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, March 1997); William J. Perry, Annual Report to the President and Congress (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, March 1996); William J. Perry, speech at the Aspen Institute Congressional Program conference, "US Relations with Russia," Dresden, Germany, August 20, 1997. Back.

Note 5: Craig Turner, "Canada's Diplomacy Coup Amazes U.S.; Ottawa's Land Mines Fight Mixed Skill and Determination," Toronto Star, August 31, 1997, p. A1; Ved Nanda, "U.S. Wise to Join Land-Mine Ban Talks," Denver Post, August 29, 1997, p. B7. Back.

Note 6: Labor organizations have often provided a channel for broad-based constructive political expression. In the 1980s and 1990s, for example, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) was instrumental in building a politically engaged nonwhite middle class in South Africa. COSATU called for peaceful marches, held strikes, and was party to negotiations with government and employers. On a global scale, an organization that has promoted social justice and internationally recognized human and labor rights is the International Labor Organization (ILO), a UN specialized agency. The ILO along with the governments of member states and their employees have created a system of international standards in all work-related areas, such as the abolition of forced labor, freedom of association, and equality of treatment and opportunity. Alan Cowell, "The Struggle: Power and Politics in South Africa's Black Trade Unions," New York Times, June 15, 1986, p. 14; Juliette Saunders, "South African Workers to Stage Nationwide Protests," Reuters European Business Report, June 18, 1995. For more information on the International Labor Organization, see their Internet site at http://www.ilo.org./. Back.

Note 7: One observer identifies four "crises" and two "revolutions" which account for the dramatic increase in NGO activities. The crisis of the modern welfare state, the development crisis brought on by the rise in oil prices and global recession in the 1970s, global environmental damage, and a crisis of socialism have all limited or delegitimized the role of governments in meeting the needs of their citizens. Increasingly, people are turning to the private sector to fill the void left by the state. The ability for collective private action has been greatly enhanced by the revolutionary growth in communications technology, which has made possible global organization and mobilization. The second revolution was brought about by the growth of the global economy in the 1960s and early 1970s. This in turn spurred the development of a middle class in many parts of the developing world. This social class has been particularly active in developing and supporting the work of NGOs in its communities. Lester M. Salamon, "The Rise of the Nonprofit Sector," Foreign Affairs 73, No. 4 (July/August 1994), pp. 109-122; Jessica T. Mathews, "Power Shift," Foreign Affairs 76, No. 1 (January/February 1997), pp. 50-66.

As mentioned earlier, NGOs can also provide early warning of deteriorating circumstances and suggestions regarding the best approach to conflict resolution. The London-based International Alert is a prominent example of an NGO involved in early warning and monitoring of conflict situations. Formed in 1985, the organization provides training for conflict negotiators, serves as a neutral mediator, and shares information on indicators of conflict and emergency situations. For more information, see International Alert Annual Report 1994 (London: International Alert, 1995). A more recent example is the Brussels-based International Crisis Group that was formed in 1995 and focuses primarily on trying to mobilize governments and international organizations to take preventive action. Back.

Note 8: See Thomas G. Weiss and Leon Gordenker, eds., NGOs, the UN, and Global Governance (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1996). Back.

Note 9: See Larry Minear and Thomas G. Weiss, Mercy Under Fire: War and the Global Humanitarian Community (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1995), pp. 13-56; Thomas G. Weiss and Cindy Collins, "Operational Dilemmas and Challenges," in Humanitarian Challenges and Intervention, eds. Larry Minear and Thomas G. Weiss (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996), pp. 130-131. Back.

Note 10: Cyrus R. Vance and Herbert S. Okun, "Creating Healthy Alliances: Leadership and Coordination among NGOs, Governments and the United Nations in Times of Emergency and Conflict," in Preventive Diplomacy: Stopping Wars Before They Start, ed. Kevin M. Cahill (New York: Basic Books, 1996), pp. 194-195. Back.

Note 11: A number of international NGOs, including the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Oxfam, International Save the Children Alliance, and Lutheran World Relief, have subscribed to a common code of conduct to guide their mutual activities. This code is a voluntary agreement acknowledging the right to humanitarian assistance as a fundamental principle for all citizens of all countries. In addition, InterAction, an umbrella organization of 160 U.S. NGOs, established InterAction Private Voluntary Organization Standards to create a common set of values for each member agency to follow and to enhance the public's trust in the ideals and operations of its members. See International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and NGOs in Disaster Relief, http://www.ifrc.org/; and InterAction, PVO Standards (Washington, DC: InterAction, 1995, amended May 1, 1996). Back.

Note 12: Joe Hinds, A Guide to Peace, Reconciliation and Community Relations Projects in Ireland (Belfast, Northern Ireland: Community Relations Council, 1994), pp. 36-37; Mustafa Ceric, Vinko Puljic, Nikolaj Mrdja, and Jakob Finci, "Press Release," Inter-Religious Council in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Sarajevo, June 9, 1997. Back.

Note 13: For a detailed analysis of the role of the Community of Sant'Egidio, see Cameron Hume, Ending Mozambique's War: The Role of Mediation and Good Offices (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1994), pp. 3-4, 15-19, 33, 145.

The first direct contact between the leadership of the insurgents (RENAMO) and the FRELIMO government took place at Sant'Egidio in Rome on July 8, 1990. Not long thereafter, two members of Sant'Egidio were enlisted as primary mediators and served in that capacity for the ten rounds of peace talks held at Sant'Egidio headquarters in Rome before the General Peace Accord was signed on October 4, 1992. (Joining Bishop Jaime Goncalves on the mediation team were Sant'Egidio's founder and leader, Andrea Riccardi, and Don Mateo Zuppi, a parish priest in Rome. A fourth team member, Mario Raffaelli, represented the Italian government.) In concert with the Italian government and other governments, Sant'Egidio maintained a momentum for peace among the two parties until the accord was signed.

This diplomatic solution to the conflict, however, was only the beginning. The challenge after 1992 was to maintain the peace so that postwar reconstruction efforts could begin to rebuild the nation's economic infrastructure. The primary problem was a social one: reconciling old enemies and ministering to a brutalized generation were essential to successful implementation. Nearly all of "the best-informed observers" predicted the breakdown of the accords due to ill will, inefficient bureaucracy, and immobilizable resources. What they failed to predict, however, was the capacity of local people and institutions to create the framework for locally brokered cease-fire and conflict resolution procedures. As the representatives of Sant'Egidio knew, the grassroots churches were well placed to fulfill this role, both to bring RENAMO and FRELIMO together, and to mobilize people around reconciliation and rebuilding communities. After the war, local churches served as mediating institutions, facilitating the reintegration of RENAMO soldiers into Mozambican society. The churches' relief agencies then expanded their operations into areas previously occupied by RENAMO. Representatives of Sant'Egidio helped sponsor the training of "social integrators" to bring the reconciliation process into local communities. Scott Appleby, The Ambivalence of the Sacred: Religion, Violence and Reconciliation (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, forthcoming). Back.

Note 14: All Africa Council of Churches, "Recommendations of the Conference of Christian Churches of the Democratic Republic of Congo," Kinshasa, July 26, 1997; All Africa Conference of Churches, "Contribution of Christian Women at the Conference of Christian Churches of Congo," Kinshasa, July 25, 1997. Back.

Note 15: In Chicago, in 1993, for only the second time in history, a Parliament of the World's Religions was convened. This gathering passed a "Declaration Toward a Global Ethic." People from very different religious backgrounds for the first time agreed on core guidelines for behavior which they affirm in their own traditions. This statement attempted to clarify what religions all over the world hold in common and formulated a minimal ethic which is essential for human survival. See Hans Küng, "The Parliament of the World's Religions: Declaration of a Global Ethic," in Yes to a Global Ethic, ed. Hans Küng (New York: Continuum, 1996), pp. 2-96. Back.

Note 16: The Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs were founded by physicist Joseph Rotblat to eliminate the role played by nuclear weapons in international politics. The conferences are rooted in the common humanity of all peoples, rather than in national loyalties. Participants are invited in a personal capacity, not as representatives of governments or institutions. Pugwash urges scientists to consider the social, moral, and ethical implications of their work. There have been more than 200 Pugwash conferences, attracting over 10,000 scientists, academics, politicians, and military figures. Among their many contributions, they have laid the groundwork for the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963, the Non-Proliferation Treaty of 1968, and the Antiballistic Missile Treaty of 1972. Recently, the conferences have also begun to discuss poverty and environmental issues. Student Pugwash groups, which discuss these same issues in high schools and universities, have been formed in 24 nations; 50 chapters exist in the United States alone. "Pugwash Conferences Wins 1995 Peace Prize," Associated Press, October 13, 1995; "Rotblat: First Nuclear Protester," Reuters Information Service, October 13, 1995. Back.

Note 17: Other experiments demonstrate the power of shared, highly valued, superordinate goals that can only be achieved by cooperative effort. Such goals can override the differences that people bring to the situation, and often have a powerful, unifying effect. Classic experiments readily made strangers at a boys' camp into enemies by isolating them from one another and heightening competition. But when powerful superordinate goals were introduced, enemies were transformed into friends.

These experiments have been replicated in work with business executives and other kinds of groups with similar results. So the effect is certainly not limited to children and youth. Indeed, the findings have pointed to the beneficial effects of working cooperatively under conditions that lead people to formulate a new, inclusive group, going beyond the subgroups with which they entered the situation. Such effects are particularly strong when there are tangibly successful outcomes of cooperation—for example, clear rewards from cooperative learning in school or at work. They have important implications for childrearing and education. Ameliorating the problem of intergroup relations rests upon finding better ways to foster child and adolescent development, as well as utilizing crucial opportunities to educate young people in conflict resolution and in mutual accommodation. Back.

Note 18: See W.D. Hawley and A.W. Jackson, eds., Toward a Common Destiny: Improving Race and Ethnic Relations in America (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1995). Back.

Note 19: See E. Staub, The Roots of Evil: The Origins of Genocide and Other Group Violence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), pp. 274-283. Back.

Note 20: For one treatment of this linkage, see Nik Gowing, Media Coverage: Help or Hindrance in Conflict Prevention? (Washington, DC: Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict, 1997). Back.

Note 21: For example, Internews Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting international understanding through the innovative use of broadcast media, sponsors conflict prevention training programs on free media in the former Soviet Union. It contributes to developing independent media programming to aid public understanding of sustainable market reform and democracy and develops guidelines and codes of ethics to help former Soviet reporters cover conflict objectively without aggravating tensions. Internews has worked closely with local nongovernmental media to provide training, equipment, technical and organizational know-how, and news exchanges to help develop objective journalism at the national, regional, and local levels. Seminars have been initiated to strengthen television journalists' sense of responsibility, impartiality, and accuracy in reporting conflicts, and to heighten their awareness of the devastating effects of irresponsible reporting. The program consists of ten week-long seminars on the coverage of ethnic conflict, balanced news reporting, station management, and technical aspects of production.

Also working in the former Soviet Union is the Commission on Radio and Television Policy, cochaired by former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Eduard Sagalaev, president of the Moscow Independent Broadcasting Corporation. The commission is made up of 50 respected figures from the mass media, academia, and public survey institutions in the former Soviet Union, Europe, and the United States. Commissioners gather annually to debate media issues and adopt recommendations based on analyses of working groups. Prior working groups have dealt with issues such as television coverage of minorities and changing economic relations arising from democratization, privatization, and new technologies. The commission has also published two policy guidebooks which have been translated into more than a dozen languages, and are used by governmental and nongovernmental groups in the former Soviet Union, Eastern and Central Europe, the Middle East, and Ethiopia. See Television and Elections (1992) and Television/Radio News and Minorities (1994). Back.

Note 22: See Voice of America, Conflict Resolution Project Annual Report (Washington, DC: Voice of America, 1997). Back.

Note 23: Trevor Findlay, Cambodia: The Legacy and Lessons of UNTAC, SIPRI Research Report No. 9 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995); James A. Schear, "Riding the Tiger: The UN and Cambodia," in UN Peacekeeping, American Policy, and the Uncivil Wars of the 1990s, ed. William J. Durch (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996), pp. 135-191; John M. Sanderson, "Preparation for Deployment and Conduct of Peacekeeping Operations: A Cambodia Snapshot," in Peacekeeping at the Crossroads, eds. Kevin Clements and Christine Wilson (Canberra: Australian National University, 1994). According to James Schear, who served as an assistant to the head of UNTAC, Yasushi Akashi, Radio UNTAC "gained a reputation as the most popular and credible radio station in the country, and was widely listened to in Khmer Rouge areas." Back.

Note 24: The growing importance and influence of an increasingly effective women's rights movement was reflected in the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, attended by more than 30,000 women representing 189 countries. The significance of this event lies not only in its opportunity for women from around the world to meet and discuss issues of transnational concern, but also to learn ways to facilitate deeper contact. In particular, the conference emphasized electronic networking as a means by which women might gain access to information and share ideas on a worldwide basis, a resource not available a few years ago. See Human Rights Watch, Human Rights Watch World Report 1996 (Washington, DC: Human Rights Watch, 1996), p. 351; further information can be found at the UN website, Women, the Information Revolution and the Beijing Conference, http://www.un.org/dpcsd/daw/. Back.