|

|

|

|

Final Report With Executive Summary

Carnegie Corporation of New York

1997

4. Structural Prevention

Strategies To Address the Root Causes of Deadly Conflict

Structural prevention—or peace building—comprises strategies to address the root causes of deadly conflict, so as to ensure that crises do not arise in the first place, or that, if they do, they do not recur. Those strategies include putting in place international legal systems, dispute resolution mechanisms, and cooperative arrangements; meeting people's basic economic, social, cultural, and humanitarian needs; and rebuilding societies that have been shattered by war or other major crises.

It will be seen that peace-building strategies are of two broad types: the development, by governments acting cooperatively, of international regimes to manage the interactions of states, and the development by individual states (with the help of outsiders as necessary) of mechanisms to ensure bedrock security, well-being, and justice for their citizens. Too often in the past, these activities have been given less attention than they deserve, partly because their conflict prevention significance has been less than fully appreciated.

It will be seen that peace-building strategies are of two broad types: the development, by governments acting cooperatively, of international regimes to manage the interactions of states, and the development by individual states (with the help of outsiders as necessary) of mechanisms to ensure bedrock security, well-being, and justice for their citizens. Too often in the past, these activities have been given less attention than they deserve, partly because their conflict prevention significance has been less than fully appreciated.

This chapter discusses both the international and national dimensions of structural prevention. It argues that, while there are no vaccines to immunize societies against violence, a number of measures promote conditions that can inhibit its outbreak. By and large, these measures must be generated and sustained in the first instance within states, through a vibrant social contract between societies and their governments. This positive interaction allows citizens to thrive in a stable environment based on equity and justice in their political and economic lives, and it is characteristic of successful states. The central argument of this chapter is that such states are less likely to succumb to widespread internal violence and less likely, as well, to fight other states.

There are many international laws, norms, agreements, and arrangements—bilateral, regional, and global in scope—designed to minimize threats to security directly. 1 Numerous arms control treaties exist, as do legal regimes like the Convention on the Law of the Sea, and dispute resolution mechanisms like the International Court of Justice and that in the World Trade Organization. These various regimes help reduce security risks by codifying the broad rules by which states can live harmoniously together and by putting in place processes by which they can resolve disputes peacefully as they arise. They also provide institutional frameworks through which states can engage in dialogue and cooperate more generally on matters affecting their national interests. As noted earlier, in 1997 no open hostilities existed between states; the peace that prevails is in part due to the effectiveness of these regimes. 2

This report argues that whatever model of self-governance societies ultimately choose, and whatever path they follow to that end, they must meet the three core needs of security, well-being, and justice and thereby give people a stake in nonviolent efforts to improve their lives. Meeting these needs not only enables people to live better lives, it also reduces the potential for deadly conflict.

People cannot thrive in an environment where they believe their survival to be in jeopardy. Indeed, many violent conflicts have been waged by people trying to establish and maintain their own security.

There are three main sources of insecurity today: the threat posed by nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction; the possibility of conventional confrontation between militaries; and internal violence, such as terrorism, organized crime, insurgency, and repressive regimes.

Nuclear Weapons

As Presidents Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev made clear, any use of nuclear weapons would be catastrophic. Moreover, the proposition that nuclear weapons can be retained in perpetuity and never be used—accidentally or by design—defies credibility. As already pointed out with respect to nuclear proliferation, the retention of nuclear weapons by any state stimulates other states and nonstate actors to acquire them. Given these facts, the only durably safe course is to work toward elimination of weapons within a reasonable time frame, and for this good purpose to be achieved, stringent conditions have to be set to make this feasible with security for all. These conditions must include rigorous safeguards against any nuclear weapons falling into the hands of dictatorial and fanatical leaders. Steps that should be taken promptly in this direction include developing credible mechanisms and practices: 1) to account for nuclear weapons and materials; 2) to monitor their whereabouts and operational condition; and 3) to ensure the safe management and reduction of nuclear arsenals.

As the Canberra Commission on the Elimination of Nuclear Weapons pointed out in 1996, "The opportunity now exists, perhaps without precedent or recurrence, to make a new and clear choice to enable the world to conduct its affairs without nuclear weapons" (see Box 4.1). 3 The work of the Canberra Commission represents a major step forward and deserves serious consideration by governments working to reduce the nuclear threat.

|

The Committee on International Security and Arms Control of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences has called for extensive improvements in the protection of nuclear weapons and fissile materials. It underscored the call for aggressive efforts to promote transparency—that is, open practices—with respect to the production, storage, and dismantling of nuclear warheads, and for efforts to ban nuclear weapons completely from specific regions and environments. In addition, the committee placed a premium on developing diplomatic strategies to clarify and to allay the legitimate security concerns of undeclared nuclear states in order to freeze, reduce, and eventually eliminate undeclared programs (see Box 4.2). 4

|

The Commission takes note of these calls, especially at this time when real progress in arms control has all but come to a complete halt, a development that raises deeply troubling issues regarding the possibility of an inadvertent nuclear attack during a crisis. As chapter 1 observed, while the threat of deliberate use of nuclear weapons by one of the major nuclear states has greatly diminished, the threat of inadvertent use has actually risen—largely due to the serious gaps that exist in control of the Russian nuclear arsenal and associated weapons-grade materials. But Russia cannot reasonably be expected to reduce the number of its warheads as long as the United States maintains its current levels. Major reductions would be beneficial for both countries and for their worldwide influence in reducing the nuclear danger.

An equitable outcome with respect to the ultimate force levels of these two nuclear powers, therefore, must be a priority. Unless it is, the arms reduction process on which the continuing viability of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) depends will remain in jeopardy.

Perhaps of greater urgency, the current operational conditions of much of the Russian inventory cannot be safely sustained. Starkly put, Moscow simply has little capacity to maintain 1,000 warheads, much less the several thousands now permitted under existing START I and START II agreements. This situation must be addressed.

Since nuclear arms are the deadliest of weapons, they create an especially critical problem of prevention. The Commission believes that preventive efforts against violence with conventional or other weapons of mass destruction would be strongly reinforced if fuller efforts were made to control the nuclear danger.

The world would be a safer place, and the risks of deadly conflict would be reduced, if nuclear weapons were not actively deployed. Much of the deterrent effect of these weapons can be sustained without having active forces poised for massive attack at every moment. The countries that maintain these active forces are the ones most threatened by the active forces of other countries, but the entire world is exposed to the consequences of an operational accident or an inadvertent attack. As long as any active deployments are maintained, moreover, the incentive and opportunity for proliferation will remain. The dramatic transformation required to remove all nuclear weapons from active deployment is feasible in technical terms, but substantial changes in political attitudes and managerial practices would be necessary as well. The Commission endorses the ultimate objective of elimination long embodied in the Non-Proliferation Treaty and recently elaborated in the reports by the Canberra Commission and the National Academy of Sciences. Precisely because of the importance of that objective, we wish to emphasize the conditions that would have to be achieved to make elimination a responsible and realistic aspiration.

In a comprehensive framework to achieve that objective, the foremost requirement would be an international accounting system that tracks the exact number of fabricated weapons and the exact amounts of the fissionable materials that provide their explosive power. This accounting is now done individually by the five countries that maintain acknowledged nuclear weapons deployments and presumably by the three countries that are generally believed to have unacknowledged weapons inventories or capability. These countries do not provide enough details to each other or the international community as a whole to the extent that would be required to determine how many nuclear weapons and how much fissionable material actually exists, where it is, and what the arrangements for its physical security are. Unless these basic features are known and monitored with reasonable confidence by an agreed mechanism, it will not be possible to reach agreement on removing nuclear weapons from active deployment.

For technical as well as political reasons, it will inevitably require a considerable amount of time to develop an accounting system that could support a general agreement to eliminate active nuclear weapons deployments. The requisite accuracy is not likely to be achieved until such a system has been in operation over a substantial period of time. The Commission strongly recommends that efforts be initiated immediately to create such a system as a priority for the prevention of deadly conflict.

Concurrently, governments should eliminate the practice of alert procedures (e.g., relying on continuously available weapons) and set an immediate goal to remove all weapons from active deployment—that is, to dismantle them to the point that to use them would require reconstruction. In addition, the major nuclear states should reverse their commitment to massive targeting and establish a presumption of limited use. Finally, as this process proceeds, multilateral arrangements will need to be made to ensure stability and the maintenance of peace and security in a world without nuclear weapons. 5

Regional Contingencies

Managing the volatile relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War rested on high-quality deterrence and avoiding the conditions that could lead to a massive accident. It was important that the two superpowers were not immediate neighbors in any meaningful sense and—with the important exception of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962—never posed any direct threat to each other. The geographic distance between Washington and Moscow was an important component of the deterrent relationship. It helped account for the fact that circumstances never arose to produce the simultaneous mobilization of forces against each other that could have led to a nuclear attack.

In several regions of the world today, however, volatile circumstances involve neighbors, one or more of which may possess nuclear weapons. These circumstances give added impetus to developing improved methods of accounting and safeguarding nuclear weapons and materials. The aim must be to remove the specter of nuclear weapons far to the background of any conventional confrontation. For this to happen, the nuclear states must demonstrate that they take seriously Article VI of the NPT (which calls for signatories to make good faith progress toward complete disarmament under strict and effective international control). Movement along the lines discussed above can help send that message throughout the world.

Biological and Chemical Weapons

Although there have been numerous protocols, conventions, and agreements on the control and elimination of biological and chemical weapons, progress has been slowed by a lack of binding treaties with provisions for implementation, inspection, and enforcement. 6 The 1972 Biological Weapons Convention, for instance, includes no verification measures, and the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention has yet to be ratified by a number of the major producers, including Russia.

As chapter 1 argued, it is impossible to control completely or deny access to materials and information regarding biological weapons. But it may be possible to gain greater control through mechanisms to monitor the possession and the construction of facilities for the most dangerous pathogens. A registry could be established in which governments and other users would register strains under their control and detail the purposes of experimentation. Registrants would be required to publish the results of their experiments. This registry would seek to reinforce the practice of systematic transparency and create a legal and professional expectation that those working with these strains would be under an obligation to reveal themselves. In addition, the professional community of researchers and scientists must engage in expanded and extensive collaboration in this field and establish close connection to the public health community. Here too, the United States and Russia should set an example for others.

The Commission believes that governments should seek a more effective categorical prohibition against the development and use of chemical weapons. The international community needs systematic monitoring of chemical compounds and the size of stockpiles to ensure transparency and to guard against misuse. 7

If progress on these fronts is to be made, complex disagreements within both the international community and individual states must be addressed. Notwithstanding its shortcomings, the experience gained on the nuclear front has created important expectations of transparency, accountability, and reciprocity, and may help improve the control of biological and chemical weapons (see Box 4.3). 8

|

Conventional Weapons

As noted in earlier chapters, violent conflict today is fought with conventional weapons. The Commission recognizes that all states have the right to maintain adequate defense structures for their security and that achieving global agreement on the control of weapons will be difficult. Nevertheless, progress should be possible to control the flow of arms around the world. The global arms trade in advanced weapons is dominated by the five permanent members of the UN Security Council and Germany. Jointly, they account for 80-90 percent of such activity. 9 The Middle East remains the largest regional market for weapons, with Saudi Arabia the largest single purchaser. East Asia, with even wealthier states modernizing their defense forces, is also a huge weapons market. To date, few efforts to control the flows of conventional weapons have been undertaken (see Box 4.4).

|

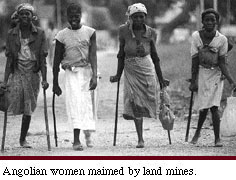

The trade in small arms and ammunition—which account for the majority of deaths in today's conflicts—remains largely unregulated, a condition that is also exploited by private arms dealers and transnational criminal elements, including narcotics cartels. 10 The first step toward regulation has been documenting arms transfers, notably the UN Register of Conventional Arms and the Wassenaar Arrangement.

The UN Register of Conventional Arms, established in 1991, provides for the voluntary disclosure of national arms transfers of major conventional weapons systems. Although a valuable source of information on arms transfers, the register's effectiveness suffers as a result of shortcomings, most notably the failure of many countries to submit information on transfers: some states failed to respond after the first two years, while others filed "nil returns," indicating no such arms exchanged. 11 In short, the quality and quantity of information in the register is not adequate to provide true transparency for conventional armaments.

|

The Wassenaar Arrangement for Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies was created in 1995 as a follow-on to the NATO-based Coordinating Committee on Multilateral Export Controls (COCOM). Named after the suburb of The Hague where the agreement was signed, the arrangement includes 33 participating countries and seeks to avoid destabilizing transfers of weapons and sensitive technologies through the coordination of national export control policies. To date, it has focused nearly exclusively on major weapons systems and not on small arms, but one option under discussion is to restrict all conventional arms transfers into certain areas at risk for renewed violent conflict or under UN sanctions.

Again, the results have been less than promising. The group concluded its December 1996 plenary session without reaching its goal of enhancing new export control guidelines. However, participation in the exchange of conventional arms and dual-use technology transfer information between members has greatly improved since the first exchange in September 1996. 12 Nevertheless, without ongoing consultations or veto powers for its members, it is unclear whether the Wassenaar Arrangement can effectively serve as a forum for resolving disputes over transfers of conventional weapons and dual-use technology (see Box 4.5).

|

The Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty (CFE) is the only international agreement to impose limits on conventional arms. In force in 1992, the CFE limits five types of conventional weapons: tanks, armored combat vehicles, artillery, attack helicopters, and combat aircraft. A side agreement known as CFE-1A places limits on manpower in Europe. The treaty provides for a multilayered verification system consisting of on-site inspections and national and multinational technical means. More than 50,000 pieces of military equipment have been destroyed or converted to other uses under the treaty. The states party to the treaty engaged in CFE Treaty Review Conferences to adapt the treaty to the changing security situation of Europe. 13

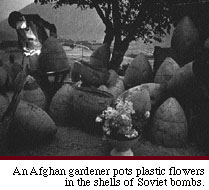

Within countries, some efforts to rein in small arms through exchange or buy-back programs have met with a measure of success. Nations such as El Salvador, inundated with weapons acquired during civil war, have initiated gun buy-back programs. 14 In Mozambique, a small church-based buy-back program provides farms tools, sewing machines, and other essential household items in return for guns and armaments. 15 These models may be adaptable to other regions by governments committed to controlling conventional weapons.

As previously mentioned, the momentum behind steps to reduce and restructure conventional military establishments will likely continue for many states. Governments must keep conventional arms control near the top of their national and multilateral security agendas to preserve the gains that have been made. NATO and other regional arrangements that offer the opportunity for sustained dialogue among the professional military establishments will help, and in the process promote important values of transparency, nonthreatening force structures and deployments, and civilian control of the military.

Cooperating for Peace

Around the globe, national military establishments in many—but not all—regions are shrinking and their role has come under profound reexamination as a result of the end of the Cold War and the sharp rise of economic globalization. With the end of the confrontation between East and West, military establishments in the former Warsaw Pact are being reconfigured and the forces of NATO and many Western nations are being reduced. Moreover, rapid and widespread global economic competition has put pressure on governments to redirect resources away from military expenditures toward social programs and other initiatives to accelerate economic growth, and this appears to be the likely course for many states for the foreseeable future.

The Commission recognizes, of course, that this phenomenon is not universal. A noteworthy exception to this trend is East Asia, where many nations have increased their military expenditures.

16

Some states continue to support disproportionately large military establishments at huge cost. In North Korea and the former Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro), for example, military spending accounts for more than 20 percent of the gross domestic product.

17

The Commission believes, however, that the general trend toward force reduction and realignment, the current absence of interstate war in the world, and the continuing development of international regimes form a foundation from which states can continue to reduce the conventional military threat that they pose to one another.

The Commission recognizes, of course, that this phenomenon is not universal. A noteworthy exception to this trend is East Asia, where many nations have increased their military expenditures.

16

Some states continue to support disproportionately large military establishments at huge cost. In North Korea and the former Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro), for example, military spending accounts for more than 20 percent of the gross domestic product.

17

The Commission believes, however, that the general trend toward force reduction and realignment, the current absence of interstate war in the world, and the continuing development of international regimes form a foundation from which states can continue to reduce the conventional military threat that they pose to one another.

One important regional initiative to help improve the security climate is NATO's Partnership for Peace (PFP). This program, formalized by the North Atlantic Council in January 1994, allows non-NATO states, particularly the former Communist nations of Eastern Europe, to enter into bilateral agreements with the North Atlantic Alliance, provided that they agree to the principles of the North Atlantic Treaty. PFP invited these states to participate in political and military bodies of NATO to widen and deepen European security and cooperation. Twenty-seven states participated in PFP in 1997. This ambitious program has helped underscore the importance and viability of three essential factors to reduce conventional military threats: transparency—that is, mutual awareness of defense expenditures and force composition—nonoffensive force structures and deployments, and civilian control of the military as an essential feature of democratic governance. The goals of the Partnership for Peace are also reinforced through bilateral programs of major NATO members. 18

Beyond NATO, other regional organizations have an active agenda to reduce threats and build confidence. In Asia, the ASEAN Regional Forum was created for just such a purpose and now brings together some 20 nations for regular consultations. 19 The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) has in the past two decades proved to be a valuable forum for confidence building in Europe.

Finally, many states pursue a number of specialized military-to-military initiatives, tailored to their specific circumstances, to help reduce external threats. The South African government, for example, has undertaken military cooperation programs with other nations of the Southern African Development Community, many of whom were involved in military confrontations with South Africa during the apartheid era. Israel and Egypt have maintained a peaceful border (albeit with significant outside help) for over 20 years. Brazil and Argentina have created the Argentinean-Brazilian Agency for Accounting and Control of Nuclear Materials (ABACC) and established a Common System of Accounting and Control of Nuclear Materials (SCCC). These steps have proven an invaluable means of developing trust and cooperation between Brazil and Argentina and have spawned a number of agreements, safeguards, protocols, and subsidiary organizations. 20

But while the general international environment is moving to greater stability between states—indeed many countries exist today in regions or subregions with absolutely no fear of outside military exploitation—in many countries a major risk still arises from internal threats.

Security within States

Intrastate violence can result from active insurgencies, political terrorism, or organized crime. Four essential elements provide a framework for maintaining a just regime for internal stability: a corpus of laws that is legitimately derived and widely promulgated and understood; a consistent, visible, fair, and active network of police authority to enforce the laws (especially important at the local level); an independent, equitable, and accessible grievance redress system, including above all an impartial judicial system; and a penal system that is fair and prudent in meting out punishment. 21 These basic elements are vitally significant yet hard to achieve, and they require constant attention through democratic processes.

Of course, not all states are democratic; some are centralized and repressive while others have weak or corrupt central governments. In such cases, this framework will not be used until major reform is undertaken. It is often the case that precisely because chances for such reforms are so remote that internal violence erupts and can last for years. Later in this chapter we discuss transitions from authoritarian to democratic government.

Important factors contributing to internal security can be derived from peace agreements that ended civil wars in Guatemala, El Salvador, Lebanon, Mozambique, and Nicaragua. These agreements have several common elements: a focus on devising

and implementing long-term change; the promotion and establishment of mechanisms for national consensus building (e.g., constituent assemblies); provisions for the maintenance of a close and ongoing relationship between the former warring parties, including the establishment and maintenance of acceptable power-sharing arrangements; and an emphasis on cooperating on long-term arrangements for economic opportunity and justice. 22

Other governments, international organizations, and private agencies operating internationally have important roles to play in maintaining internal security. The UN contributed greatly to building peace in several of the countries mentioned above. In general, outsiders can help by

Promoting norms and practices to govern interstate relations, to avoid and resolve disputes, and to encourage practices of good governance

Reducing and eventually eliminating the many military threats and sources of insecurity between states, including those that contribute to instability within states

Not exacerbating the interstate or intrastate disputes of others, either on purpose or inadvertently. The history of third-party intervention is replete with examples of interventions that were unwarranted, unwanted, or unhelpful.

Existing in a secure environment is only the beginning, of course. People may feel relatively free from fear of attack, but unless they also believe themselves able to maintain a healthy existence and have genuine opportunities to pursue a livelihood, discontent and resentment can generate unrest.

What is the relationship between economic well-being and peace? If the relationship is clearly positive, what strategies to promote economic prosperity work best under what conditions? We have learned important lessons from successes and failures in Africa, Asia, and Latin America during the past half-century.

Too many of the world's people still cannot take for granted food, water, shelter, and other necessities. Why are there still widely prevalent threats to survival when modern science and technology have made such powerful contributions to human well-being? What can we do to diminish the kind of vulnerability that leads to desperation? The slippery slope of degradation—so vividly exemplified in Somalia in the early 1990s—leads to growing risks of civil war, terrorism, and humanitarian catastrophe.

Basic well-being entails access to adequate shelter, food, health services, education, and an opportunity to earn a livelihood. In the context of structural prevention, well-being implies more than just a state's capacity to provide essential needs. People are often able to tolerate economic deprivation and disparities in the short run because governments create conditions that allow people to improve their living standards and that lessen disparities between rich and poor. To this extent, well-being overlaps with political and social justice, discussed below.

Basic well-being entails access to adequate shelter, food, health services, education, and an opportunity to earn a livelihood. In the context of structural prevention, well-being implies more than just a state's capacity to provide essential needs. People are often able to tolerate economic deprivation and disparities in the short run because governments create conditions that allow people to improve their living standards and that lessen disparities between rich and poor. To this extent, well-being overlaps with political and social justice, discussed below.

The Commission believes that decent living standards are a universal human right. Development efforts to meet these standards are a prime responsibility of governments, and the international community has a responsibility to help governments through development assistance. Assistance programs are vital to many developing states, crucial to sustaining millions of people in crises, and necessary to help build otherwise unaffordable infrastructure. But long-term solutions must also be found through states' own developmental policies, attentive to the particular needs of a society's economic and social sectors. In addition, the careful management of existing natural resources is becoming increasingly vital to the welfare of all societies.

Helping from Within: Development Revisited

For a variety of reasons, many nations in the global South have been late in getting access to the remarkable opportunities now available for economic and social development. They are seeking ways to modernize in keeping with their own cultural traditions and distinctive settings. How can they adapt useful tools from the world's experience for their own development?

The general well-being of a society will require government action to help ensure widespread economic opportunity. Whether and how to undertake such strategies is controversial and should be decided and implemented democratically by societies on their own behalf. The Commission emphasizes, however, that economic growth, by itself, will not reduce prospects for violent conflict and could, in fact, be a contributing factor to internal conflicts. The resentment and unrest likely to be induced by drastically unbalanced or inequitable growth may outweigh whatever prosperity that growth generates. In contrast, equitable access to economic growth and, importantly, economic opportunity inhibits deadly conflict. 23

Unfortunately, the current international economic environment is not particularly sympathetic to this view, emphasizing instead short-term bottom-line performance as a measure of economic competitiveness and vitality. Clearly, in many states economic growth must sharply increase to meet the needs of burgeoning populations. But if this complex equation is to be managed with as little potential for deadly violence as possible, governments must reorient their thinking away from an overemphasis on short-term performance. Otherwise, there will be an avoidable excess of human suffering—with associated resentment and hence the seedbed for hatred and violence, even terrorist movements.

Fundamentally, the distribution of economic benefits in a society is a function of political decisions regarding the kind of economic system a society will construct, including the nature and level of governmental engagement in private sector activity. Poverty is often a structural outgrowth of these decisions, and when poverty runs in parallel with ethnic or cultural lines, it often creates a flashpoint. Peace is most commonly found where economic growth and opportunities to share in that growth are broadly distributed across the population.

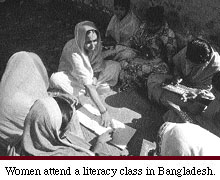

There is great preventive value in initiatives that focus on children and women, not only because they are the main victims of conflict, but also because women in many vulnerable societies are an important source of community stability and vitality. For children, this emphasis entails a two-pronged approach that stresses, on the one hand, broad opportunities for education and basic health services, and on the other, policies that prohibit the recruitment of child soldiers and the industrial exploitation of child labor. For women, this entails national programs that encourage education for girls, women-operated businesses, and other community-based activities.

A growing body of evidence shows that the education of women and girls is a remarkably promising route for developing countries. The need to improve the educational attainment and status of women is an objective of intrinsic value, but it has the added practical value of far-reaching significance in widening women's skills and choices as well as in improving their health and nutrition. It is an investment in future economic growth and well-being even when women do not participate in wage employment. Most girls in developing countries become mothers, and their influence on their children is crucial. Health studies show that the more educated the mothers, the less likely that their children will die, regardless of differences in family income. Education helps delay marriage for women, partly by increasing their chances for employment, and educated women are more likely to know about and use contraceptives. 24

Almost all countries committed themselves to the goal of eradicating severe poverty at the World Summit for Social Development in 1995.

25

Daunting though this aim is, the opportunities of the global economy and the lessons learned in development make this a reasonable goal in the next few decades. The UN Development Program's Human Development Report 1997 formulates six priorities for action:

Almost all countries committed themselves to the goal of eradicating severe poverty at the World Summit for Social Development in 1995.

25

Daunting though this aim is, the opportunities of the global economy and the lessons learned in development make this a reasonable goal in the next few decades. The UN Development Program's Human Development Report 1997 formulates six priorities for action:

Everywhere the starting point is to empower women and men—and to ensure their participation in decisions that affect their lives and enable them to build their strengths and assets.

Gender equality is essential for empowering women—and for eradicating poverty.

Sustained poverty reduction requires "pro-poor" growth in all countries—and faster growth in the 100 or so developing and transition countries where growth has been failing.

Globalization offers great opportunities—but only if it is managed more carefully with more concern for global equity.

In all these areas, the state must provide an enabling environment for broad-based political support and alliances for "pro-poor" policies and markets.

Special international support is needed for special situations—to reduce the poorest countries' debt faster, to increase their share of aid, and to open agricultural markets for their exports. 26

A complementary approach to economic development is made in the World Bank's World Development Report 1996. It derives lessons of experience from economies in transition from central planning to market-based operation—as they build essential institutions to support efficient markets with adequate social safety nets.

What can these countries learn from each other? What does the experience of transition to date suggest for the many other countries grappling with similar issues of economic reform? What are the implications for external assistance—and for the reform priorities in the countries themselves? The World Bank's report observes:

Consistent policies, combining liberalization of markets, trade and new business entry with reasonable price stability, can achieve a great deal—even in countries lacking clear property rights and strong market institutions.

Differences between countries are very important, both in setting the feasible range of policy choices and in determining the response to reforms.

An efficient response to market processes requires clearly defined property rights—and this will eventually require widespread private ownership.

Major changes in social policies must complement the move to the market—to focus on relieving poverty, to cope with increased mobility, and to counter the adverse intergenerational effects of reform.

Institutions that support markets arise both by design and from demand.

Sustaining the human capital base for economic growth requires considerable reengineering of education and health delivery systems. International integration can help lock in successful reforms.

These judgments reinforce the Commission's belief that diligent programs that help cultivate the human resources of a country, in ways that ensure widespread access to economic opportunity, will help create conditions that inhibit widespread violence.

Making Development Sustainable

Global population and economic growth, along with high consumption in the North, have led to the depletion, destruction, and pollution of the natural environment. Science and technology can contribute immensely to the reduction of environmental threats through low-pollution technologies. Greater effort is required to develop sustainable strategies for social and economic progress; in fact, sustainability is likely to become a key principle of development and a major incentive for global partnerships.

In at least three clear ways, the use and misuse of natural resources lie at the heart of conflicts that hold the potential for mass violence: 1) the deliberate manipulation of resource shortages for hostile purposes (for example, using food or water as a weapon); 2) competing claims of sovereignty over resource endowments (such as rivers or oil and other fossil fuel deposits); and 3) the exacerbating role played by environmental degradation and resource depletion in areas characterized by political instability, rapid population growth, chronic economic deprivation, and societal stress.

Serious issues of international equity will be posed by the desire of the North to preserve global climate stability and biodiversity and that of the South to secure a greater share of global resources and economic growth. Environmental problems plaguing the industrialized countries also pose equity issues, with domestic minority ethnic groups and the poor usually bearing the brunt of pollution. In the aftermath of environmental deterioration, national security systems are likely to be challenged by massive immigration to more favorably situated states.

If security analysts can be thoroughly informed about environmental problems, and if environmental analysts can come to understand the tools and experiences of the security community, there could be advances in ways to approach international environmental agreements. An example may help to clarify the nature of the problem. A critical environmental challenge of the day is limiting the emissions of carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuel. The lion's share of such emissions comes from the developed countries. But increasing numbers of people in the developing world are demanding improved standards of living, and that will lead to dramatically higher levels of combustion of fossil fuels. China's economic growth rate, for example, currently exceeds ten percent per year, and unless new energy technologies are introduced, this growth will rapidly raise the average level of carbon dioxide emissions from developing countries. Because Western standards of living have been built on inefficient uses of fossil fuels, it is likely that many developing countries will repeat that pattern as they industrialize. This will complicate North-South negotiations to attain environmentally sustainable development.

If security analysts can be thoroughly informed about environmental problems, and if environmental analysts can come to understand the tools and experiences of the security community, there could be advances in ways to approach international environmental agreements. An example may help to clarify the nature of the problem. A critical environmental challenge of the day is limiting the emissions of carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuel. The lion's share of such emissions comes from the developed countries. But increasing numbers of people in the developing world are demanding improved standards of living, and that will lead to dramatically higher levels of combustion of fossil fuels. China's economic growth rate, for example, currently exceeds ten percent per year, and unless new energy technologies are introduced, this growth will rapidly raise the average level of carbon dioxide emissions from developing countries. Because Western standards of living have been built on inefficient uses of fossil fuels, it is likely that many developing countries will repeat that pattern as they industrialize. This will complicate North-South negotiations to attain environmentally sustainable development.

Experience from past international environmental and security negotiations may be found to guide the achievement of arrangements to control carbon dioxide emissions. The Montreal Protocols of 1987 limiting production of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbon compounds involved primarily the industrialized world. But when they were extended in the London agreements two years later, substantial interest on the part of the developing countries produced significant technical aid commitments from the industrialized countries.

Economists Sudhir Anand and Amartya Sen point out that the human development perspective translates readily into a critical recognition of the need for active international efforts to preserve the quality of the environment in which we live. They write: "We have to see how the human developments we have achieved in the past, and what we are trying to achieve right now, can be sustained in the future—and further extended—rather than be threatened by pollution, exhaustion of natural resources and other deteriorations of local and global environments. But this safeguarding of future prospects has to be done without sacrificing current efforts towards rapid human development and the speedy elimination of widespread deprivation of basic human capabilities. This is partly a matter of cooperation across the frontiers, but the basis of that collaboration must take full note of the inequalities that exist now and the urgency of rapid human development in the more deprived parts of the world." 27

Helping from Outside: Development Assistance

Promoting good governance has become the keynote of development assistance in the 1990s, along with the building of fundamental skills and local capacity for participation in the modern global economy. Compared with the overarching economic priorities of previous decades—reconstruction in the 1950s, development planning in the 1960s, meeting basic human needs in the 1970s, or structural adjustment in the 1980s—current policies of the major donors are more directly supportive of structural prevention. The new approach requires a state, at a minimum, to equip itself with a professional, accountable bureaucracy that is able to provide an enabling environment and handle macroeconomic management, sustained poverty reduction, education and training (including of women), and protection of the environment.

The Commission believes that more strenuous and sustained development assistance can also reduce the risk of regional conflicts when it is used to tie border groups in one or more states to their shared interests in land and water development, environmental improvement, and other mutual concerns. Nearly every region of the world has a major resource endowment that will require multiple states to cooperate to ensure that these resources are managed responsibly. In North America, the Rio Grande Valley and the Great Lakes region are prominent examples. In Russia and Central Asia, disputes over the Caspian Sea and the Fergana Valley have already proven this point. In the Middle East, no state is immune to a deep and abiding concern regarding the distribution of fresh water.

The emphasis on good governance has also encouraged a more robust and responsible private sector development in many countries. There is rising economic activity in the private sector around the world. Over the next ten years, the World Bank projects that developing economies will grow at over twice the rate of industrialized economies. 28

Sustained growth requires investment in people, and careful programs must be crafted if deep, intergenerational poverty is not to become institutionalized. Foreign assistance to poor countries can include transitional budgetary support, especially for maintenance and to buffer the human cost of conversion to market economies. Extensive technical assistance, specialized training, and broad economic education are all badly needed. So too is the building of indigenous institutions to sustain the vital knowledge and skills for development.

In sum, improving well-being requires a multifaceted approach. It means mobilizing and developing human capacities; broadening and diversifying the economic base; removing barriers to equal opportunity; and opening countries to participation in the global economy and the international community.

|

When citizens are treated fairly and offered equal access to opportunities under the law, this, in turn, creates the political space necessary for people to fulfill their aspirations without the need to deprive others of the same opportunity. Based on the principles outlined in the UN Charter, governments should work to promulgate norms of behavior within and between states that strengthen and widen not only security and well-being, but also justice.

An understanding of and adherence to the rule of law is crucial to a healthy system of social organization, both nationally and internationally, and any effort to create and maintain such a system must itself rest on the rule of law. The rule of law is both a goal—it forms the basis for the just management of relations between and among people—and a means. A sound legal regime helps ensure the protection of fundamental human rights, political access through participatory governance, social accommodation of diverse groups, and equitable economic opportunity.

Justice in the International Community

States should develop ways to promote international law with particular emphasis in three main areas: human rights; humanitarian law, including the need to provide the legal underpinning for UN operations in the field; and nonviolent alternatives for dispute resolution, including more flexible intrastate mechanisms for mediation, arbitration, grievance recognition, and social reconciliation.

Human Rights

Norms that call for the protection of fundamental human rights are contained in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 29 The Universal Declaration bans all forms of discrimination, slavery, torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment and guarantees every human's right to life, liberty, nationality, freedom of movement, religion, asylum, marriage, assembly, and many other fundamental rights and liberties. One hundred thirty states have become signatories to the Universal Declaration since its adoption by the General Assembly on December 10, 1948. The Universal Declaration is joined by the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights with its two Optional Protocols to form the International Bill of Rights, the cornerstone of the United Nations "worldwide human rights movement" established in the Charter. 30

Many regional organizations include the International Bill of Rights in their charters and proceedings; some even add additional human rights provisions. For example, the Helsinki Accords (the founding document of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe [CSCE]) provide, as in the Universal Declaration, for freedom of thought, conscience, religion, and belief.

31

These human rights provisions were later expanded by the Charter of Paris, which undertook to protect the ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and religious identity of national minorities.

32

Many regional organizations include the International Bill of Rights in their charters and proceedings; some even add additional human rights provisions. For example, the Helsinki Accords (the founding document of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe [CSCE]) provide, as in the Universal Declaration, for freedom of thought, conscience, religion, and belief.

31

These human rights provisions were later expanded by the Charter of Paris, which undertook to protect the ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and religious identity of national minorities.

32

States have only begun to use these criteria to shape their bilateral relations. 33 Despite the unprecedented range and volume of formal endorsements that states have given human rights since the founding of the United Nations, they have been reluctant to hold each other accountable for living up to these principles. Ensuring the protection of human rights requires active engagement by responsible governments. The guidelines, political will, and international capacity for such engagement are developing very slowly, however, in the absence of a clear consensus among states that efforts on behalf of human rights are in their national interest.

Yet, the original decision to enshrine a commitment to uphold human rights in the UN Charter reflected more than a humanitarian or idealist impulse of member governments. The founders of the UN were primarily interested in preventing another world war, and many had concluded that the terrible human rights abuses by the Nazis were the early warning signs of a potential aggressor. Had the international community acted to stop Hitler and his followers, World War II might have been prevented. On this much they agreed, but they could not agree on how to prevent wars. With the onset of the Cold War, prevention reverted to more traditional strategies of deterrence and balance of power. But in the 1990s, states face new problems of collective security that give human rights greater political salience.

As the UN's High Commissioner for Refugees so often reminds governments: "Today's human rights abuses are tomorrow's refugee movements."

34

Human rights, in this sense, are gaining significance not only as a moral imperative, but also as a tool of analysis and policy formation—with their violation an early warning of worse problems to come. Situations in which governments do not respect the rights of their own citizens could be a warning that refugee flows and other troubles might spiral into costly humanitarian emergencies. Human rights are thus becoming, properly, a rationale for preventive diplomacy and collective security.

As the UN's High Commissioner for Refugees so often reminds governments: "Today's human rights abuses are tomorrow's refugee movements."

34

Human rights, in this sense, are gaining significance not only as a moral imperative, but also as a tool of analysis and policy formation—with their violation an early warning of worse problems to come. Situations in which governments do not respect the rights of their own citizens could be a warning that refugee flows and other troubles might spiral into costly humanitarian emergencies. Human rights are thus becoming, properly, a rationale for preventive diplomacy and collective security.

Several regional initiatives have been attempted in recent years to strengthen the value of human rights practices and other measures as essential factors for stability. The European Court of Human Rights and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights work within their respective regions to respond to intrastate and interstate oppression. The European Court, an organ of the Council of Europe, was founded by the European Convention on Human Rights (1953) and has proven in recent years to be one of the most successful instruments of international law. The Inter-American Court, founded by the Organization of American States in 1979, has also become a powerful voice in human rights law, both regionally through its decisions and globally through its issuance of advisory opinions. The Court is mandated to promote respect for and to defend human rights—together with the Inter-American Commission, which determines the admissibility of petitions to the Court, engages in fact-finding missions, and attempts to arrange friendly settlements. 35

One building block for promulgating humanitarian norms especially important to internal conflict is Article Three in each of the four Geneva Conventions. Common to all these conventions, it applies to all armed conflict of a "noninternational" character occurring in the territory of a signatory state. It calls for the humane treatment of noncombatants and others who do not take up arms, and prohibits violence of any type against these persons—including humiliating or degrading treatment, the taking of hostages, and all forms of extrajudicial punishment. Moreover, it requires that protections be accorded medical personnel and medical transport for the wounded and sick, and that arrangements for the dead be respectful.

But for societies wracked by years of conflict, overcoming years or even generations of violence, discrimination, and deprivation will not come easily. People must work to put the past behind them without creating a new basis for future violence. To do so, they often need the help of mediation or arbitration mechanisms.

Nonviolent Dispute Resolution

A wide array of approaches to mediation and arbitration exists to help broker disputes in nonviolent ways. Arbitration, the more limited of the two mechanisms, seems to work best under conditions of defined legal relationships such as international trade agreements. Arbitration clauses are often laid out in treaties and charters where members or signatories agree, in advance, to arbitrate disputes before a conflict escalates. This form of conflict resolution is limited by the fact that it takes place in a confrontational and defined framework within a judicial or quasi-judicial environment. The presence of appointed representatives and a decisive third-party role minimizes direct communication between the parties in conflict. 36 The Court of Conciliation and Arbitration, established by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in 1994, offered dispute resolution between consenting states in Europe and the former Soviet Union. Its rulings are legally binding on signatories to the Convention on Conciliation and Arbitration, and its conciliation procedures make it an attractive alternative for the settlement of disputes. 37

Mediation, on the other hand, enjoys a higher rate of success in international application. It requires no advance commitment, allows conflicting parties to communicate directly, and has as its goal simply to settle the conflict to the satisfaction of all parties. Mediation has been used extensively as a tool for dealing with both interstate and internal conflicts. The civil wars in El Salvador and Mozambique and the dispute between Greece and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia were resolved through mediation. 38

Less promising for the management and prevention of violent conflict is the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Its weak record on issues of conflict and peace is well documented. Over its life, it has decided about 100 cases, and only a handful have related to serious security issues. Controversies leading to deadly conflict are not often disputes about legal rights and obligations; they are political disputes involving perceived national interests, and countries have proven consistently unwilling to expose themselves to external adjudication. Many of the states that accept the Court's jurisdiction have reservations that exclude disputes involving national security and similar cases. The Court's relevance to intrastate conflict is severely limited by the fact that only states may be parties to cases brought before it. By their nature, the ICJ's legal proceedings intensify the confrontational and adversarial aspects of disputes, at least in the short run. Over the years, interesting suggestions have been made to strengthen the Court, e.g., in the appointment and functioning of judges and in greater use of advisory opinions. It remains to be seen whether the Court could become more effective in preventing deadly conflict.

Notwithstanding the limitations of the Court, the Commission believes that it has a role in helping to clarify contentious issues and legitimate norms of behavior among states. Governments should take steps to strengthen the Court for these purposes.

Justice within States

There is perhaps no more fundamental political right than the ability to have a say in how one is governed. Healthy political systems reflect a shared contract between the people and their government that, at its most basic, ensures the ability to survive free from fear or want. Beyond basic survival, however, participation by the people in the choice and replacement of their government—democracy—assures all citizens the opportunity to better their circumstances while managing the inevitable clashes that arise. Democracy achieves this goal by accommodating competing interests through regularized, widely accessible, transparent processes at many levels of government. Sustainable democratic systems also need a functioning and fair judicial system, a military that is under civilian control, and a police and civil service that are competent, honest, and accountable. 39

Effective participatory government based on the rule of law reduces the need for people to take matters into their own hands and resolve their differences through violence. It is important that all groups within a society believe that they have real opportunities to influence the political process. 40 The institutions and processes to ensure widespread political participation can vary widely.

A state's internal political system influences its dealings with other states. It is now commonplace to note that democratic states tend not to fight one another. Despite some constraints and qualifications, this basic thesis stands up remarkably well to scrutiny. 41 Democratic states do not agree on everything, but their habits of negotiation and tolerance of domestic dissent tend to resolve conflicts well short of military action. In their dealings with each other, these states sometimes create new institutions and processes to meet new demands, such as the dispute resolution mechanisms in global economic organizations (some of which were discussed in chapter 3).

Transition to Democracy

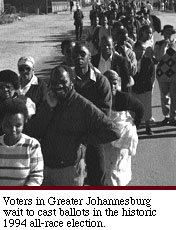

Where the practice of democracy is lacking, how can it be created peacefully? This question is crucial for the many countries on several continents that are moving toward participatory government. Across Africa, arduous transitions are now under way in what UN Secretary- General Kofi Annan describes as a "Third Wave" of lasting peace based on democracy, human rights, and sustainable development. During five tumultuous decades, Africans first struggled with decolonization and apartheid, followed by a second wave of civil wars, the tyranny of military rule, and economic stagnation. But by the late 1990s difficult and diverse democratic transitions were under way in Benin, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and elsewhere.

Engineering transitions to participatory governance, or restoring legitimate governance following conditions of anarchy, may require temporary power sharing. Many forms of power sharing are possible, but all provide for widespread participation in the reconstruction effort, sufficient resources to ensure broad-based access to educational, economic, and political opportunities, and the constructive involvement of outsiders (see Box 4.6). 42 Strong civil society has been important to the transition process in Eastern Europe. The transition to democracy in states with long or severe repression of civil society (e.g., Albania, Belarus, and Bulgaria) has been much more difficult than the transition in states where social cohesion and institutions of civil society have been stronger (e.g., the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland). In some extreme cases, Albania in 1997, for example, the transition to democracy may require temporary international intervention to reestablish law and order.

|

In transitions from military rule—in Argentina (1983), Chile (1989), Haiti (1995), and Turkey (1983)—the key to avoiding widespread bloodshed was a combination of a politically weakened core of military rulers and strong internal and external pressures. A military regime may be unable to deal simultaneously with dramatic political, institutional, and economic change (as was the case in Chile), or growing popular support for democracy combined with military overextension or failure (as was the case in Argentina). 43 Other characteristics of transformation from military to civilian rule include growing uneasiness within the military about its own legitimacy in power, a failure to win over the public, the widespread disrepute of single-party regimes, and increased pressures from international financial institutions and the business community for greater openness. Also important are a willingness to expand political participation and constant public pressure supported by other governments, international organizations, and NGOs. 44

In the aftermath of authoritarian regimes or civil wars characterized by atrocities, the legitimacy of the reconciliation mechanisms is paramount. At least three ways exist to bring perpetrators to justice and help move societies forward: aggressive and visible use of the existing judicial system; establishment of a special commission for truth and reconciliation; or reliance on international tribunals. For example, Germany, after unification, remanded those accused of criminal behavior to the existing systems of justice. In Argentina, Chile, El Salvador, and South Africa, truth and reconciliation commissions have proven essential for airing grievances and bringing criminals to justice (see Box 4.7). 45 Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia have relied on the establishment of an international tribunal.

|

International tribunals serve important accountability, reconciliation, and deterrence functions, inasmuch as they provide a credible forum to hear grievances and a legitimate process through which individuals rather than an entire nationality are held accountable for their transgressions. Notwithstanding a number of serious problems, the tribunals do, according to one scholar, challenge any notion leaders may have that they can precipitate mass violence or genocide with impunity, and they have set important precedents on such key legal issues as competence and jurisdiction. 46 The Commission believes that the United Nations should move to establish an international criminal court, and it welcomes the secretary-general's proposal that an international conference be held in 1998 to finalize and adopt a treaty to establish such a court. 47

Many institutions of civil society have a key role to play in reconciliation, including religious institutions, the media, community organizations, and educational institutions. Though lacking the binding force of law, their efforts can be decisive. The following chapter discusses the role of these institutions in greater detail.

Proliferation of organized political parties demonstrates one way in which political participation can be expanded. A number of other elements are at least of equal importance to the democratizing process: a free and independent media through which citizens can communicate with each other and their government; equitable access to economic opportunities—including civil service and other state employment—fair and balanced taxation systems; an independent judiciary; constitutional or statutory national institutions to promote and protect human rights (see Box 4.8); equitable representation in high-level government positions; and uniform rules for conscription to military service to preserve the legitimacy of the official military arm of the state. 48

|

In short, the right to a say in how one is governed is a fundamental human right and the foundation of a political framework within which disputes among groups or their members can be brokered in nonviolent ways. But merely giving people a say will not, of itself, ensure political accommodation. People must believe that their government will stay free of corruption, maintain law and order, provide for their basic needs, and safeguard their interests without compromising their core values.

Social Justice

While democratic political systems strive to treat people equally, this does not mean that they treat all people the same. Just as efforts are made to accommodate the special needs of the very old, the very young, the poor, and the disabled, it is usually necessary to acknowledge explicitly the differences that may exist among various groups within a society and accommodate to the greatest extent possible the particular needs these groups may have. Among the most important needs are the freedom to preserve important cultural practices, including the opportunity for education in a different language, and freedom of religion.

These issues are politically explosive, even in such open societies as Canada and the United States. The "English only" debate in the United States, for example, reveals the extent to which some people perceive that providing entitlements for one group—in this case most notably, Spanish-speaking Americans—would erode their own. In Canada, the Quebec separatist movement was put into a wider context, in part, by the prospect that the province itself might be subject to further division from native Indians and Inuit seeking their own cultural autonomy. 49

One solution is to permit cultural and linguistic groups to operate private educational institutions. Another is to mandate dual-language instruction. In South Africa, for example, in an effort to ensure cultural self-

determination of groups in the country, the new constitution recognizes 11 official languages, and students have the right to an education in the language of their choice. In India, where English is widely used, the constitution lists 18 official languages, all of which are indigenous to the country. Belgium has adopted many laws and practices to accommodate its linguistic communities—broad authority over cultural, educational, and linguistic matters has been granted to "communities" representing the Flemish, French, and German-speaking populations of the country. 50 Switzerland has successfully maintained national unity while protecting four distinct cultures and three linguistic groups within its boundaries. Canada enacted a policy of bilingualism and multiculturalism in 1971. In the United Kingdom, the Welsh Language Act of 1993 granted Welsh equal status with English in Wales. 51

On the other hand, use of a single language can have a unifying effect in certain circumstances. In Tanzania, for example, notwithstanding many other problems the country faces, the dozens of ethnic groups now all speak Swahili—giving all of Tanzania's peoples a sense of national cohesion.

Scholars and policymakers alike are still trying to understand post-Communist rule in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Of particular importance, in addition to the role of leaders and social cohesion, has been the accommodation of minority groups (see Box 4.9), especially those with ethnic kin states bordering their host countries, such as ethnic Albanians, Armenians, Hungarians, Russians, and Serbs in Europe. One scholar, after a comprehensive examination of disadvantaged minority groups throughout the world, concludes: "The most important spillover effects in communal conflict occur among groups that straddle interstate boundaries" (see Box 4.10). 52 Circumstances of minorities abroad demand open channels of dialogue between capitals, channels that can also help keep tension between these states at a low level.

|

|

The ability of groups to engage in cultural or religious practices that differ from the majority of the population must also be preserved. Many states have created an environment in which people can demonstrate and benefit from mutual respect for different cultural and religious traditions. In Cyprus, to cite a small but instructive example, where Greek and Turkish Cypriot leaders remain unable to resolve their own differences, the small population of Maronite Christians is able to travel across the Green Line in Nicosia and practice its faith.

Simply put, vibrant, participatory systems require religious and cultural freedom. As Hans Küng noted: "The survival of humanity is at stake. . . . There will be no peace among the nations without peace among the religions." 53

It is worth repeating the fundamental point of this chapter: security, well-being, and justice not only make people better off, they inhibit the tendency to resort to violence. But how are these conditions achieved? What are the roles of governments, international organizations, and civil society in improving security, well-being, and justice, and what are their roles in helping to prevent deadly conflict? The following chapter examines these questions.

Notes

Note 1: The role of international regimes in conflict prevention is further developed in Gareth Evans, Cooperating for Peace (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1993), pp. 39-51. Back.

Note 2: International organizations and regimes have a long history of peaceful dispute settlement. The United Nations has functioned as a forum for international dispute resolution since its establishment; for example, see the discussion of the case of Bahrain in the prologue. The World Trade Organization (WTO) and European Union (EU) have well-established dispute resolution mechanisms. The WTO's Dispute Resolution Body (DRB) rules continually on a number of trade conflicts between member states, including, for example, a complaint against the United States by Venezuela and Brazil over U.S. gasoline regulations, settled in 1996, and a complaint against Japan by the United States, EU, and Canada over alcoholic beverages, also settled in 1996. The EU has been a force for peaceful resolution of conflict in political as well as economic disputes. The Conference on Stability in Europe, established in May 1994, brought more than 40 European states together to resolve disputes over borders and the treatment of minorities. Only two months later, Hungary renounced territorial claims against Romania and Slovakia. (Nicholas Denton, "Hungary Acts on Borders," Financial Times, July 15, 1994, p. 2; Patrick Worsnip, "Talks on Stability Fan Old Enmities," The Independent, May 28, 1994, p. 7.) A number of states with sea-going interests, including those at critical maritime locations with heated disputes such as Yemen, Eritrea, Qatar, and Bahrain, have agreed to have their differences settled according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. For instance, in 1995, Guinea-Bissau and Senegal settled their dispute over territorial waters through the International Court of Justice and the Convention on the Law of the Sea. (More information on the dispute settlement mechanisms of the WTO and the Law of the Sea may be found at their websites: http://www.wto.org/wto/dispute/dispute.htm, and http://www.un.org/depts/los) Back.

Note 3: Canberra Commission on the Elimination of Nuclear Weapons, Report of the Canberra Commission on the Elimination of Nuclear Weapons (Canberra Commission on the Elimination of Nuclear Weapons, August, 1996), p. 7. Back.

Note 4: Committee on International Security and Arms Control, National Academy of Sciences, The Future of the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Policy (Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1997), pp. 1-10. Back.

Note 5: At the urging of the United Nations General Assembly, the International Court of Justice offered an advisory opinion, issued in 1996, on the question "Is the threat or use of nuclear weapons in any circumstance permitted under international law?" The Court observed that a threat or use of force by means of nuclear weapons that is contrary to Article 2, paragraph 4, of the United Nations Charter and that fails to meet all the requirements of Article 51 is unlawful. Further, the Court found that the threat or use of nuclear weapons must be compatible with the requirements of the international law applicable in armed conflict, particularly those of the principles and rules of international humanitarian law, as well as with specific obligations under treaties and other undertakings which expressly deal with nuclear weapons. Yet the Court could not reach a definitive conclusion as to the legality or illegality of the use of nuclear weapons by a state in an extreme circumstance of self-defense, in which its very survival would be at stake. The Court suggested that international law and the stability of the international order, which it is intended to govern, will suffer from the continuing difference of views with regard to the legal status of weapons as deadly as nuclear weapons. As a result, it unanimously agreed that an obligation exists to pursue and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament in all aspects under strict and effective international control. "Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons," Advisory Opinion, International Court of Justice, General List No. 95, July 8, 1996. Back.

Note 6: There are five major documents which address chemical and biological weapons identified in international law: 1) "Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare," February 8, 1928, Treaties and Other International Acts Series (T.I.A.S.) no. 9433; 2) "Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, and Stockpiling of Bacterial (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction," March 26, 1975, T.I.A.S. no. 9433; 3) "Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction," April 29, 1997, 32 International Legal Materials (I.L.M.) 932 (1993); 4) "Agreement Between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on Destruction and Non-Production of Chemical Weapons and on Measures to Facilitate the Multilateral Convention on Banning Chemical Weapons," 29 I.L.M. 932 (1990); 5) "Declaration on the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons," 28 I.L.M. 1020 (1989). Back.

Note 7: For discussions of some of the issues which have slowed progress on chemical and biological arms control, see Committee on International Arms Control and Security Affairs of The Association of the Bar of the City of New York, Achieving Effective Arms Control: Recommendations, Background and Analysis, The Association of the Bar of the City of New York, 1985, pp. 115-118; Frederick J. Vogel, The Chemical Weapons Convention: Strategic Implications for the United States, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, Carlisle Barracks, PA, 1997, pp. 8-11. For general and up-to-date information on the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), implementation and enforcement of the CWC and the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), see Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, The OPCW Home Page, http://www.opcw.nl/, updated June 10, 1997. Back.