|

|

|

|

Final Report With Executive Summary

Carnegie Corporation of New York

1997

2. When Prevention Fails

How and Why Deadly Conflict Occurs

Understanding Violent Conflict

In the post-Cold War era, most violent conflict can be characterized as internal wars fought with conventional weapons, with far greater casualties among civilians than soldiers. None is spontaneous: someone is leading the groups that are willing to fight. This harsh reality may help us understand a simple truth: war remains primarily an instrument of politics in the hands of willful leaders.

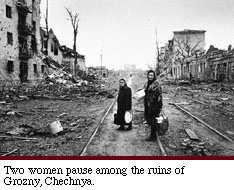

Yet in many parts of the world, diverse peoples coexist in peace. Cultural distinctions, religious differences, or ethnic diversity may sharpen disagreements, but these factors do not alone determine why these differences become violent. Serbs, Croats, and Bosnians coexisted in relative calm since World War II, and in some respects even for centuries, before the violence erupted in the former Yugoslavia in 1991. Chechens had declared independence from Russia three years before the shelling of Grozny began in 1994.

Yet in many parts of the world, diverse peoples coexist in peace. Cultural distinctions, religious differences, or ethnic diversity may sharpen disagreements, but these factors do not alone determine why these differences become violent. Serbs, Croats, and Bosnians coexisted in relative calm since World War II, and in some respects even for centuries, before the violence erupted in the former Yugoslavia in 1991. Chechens had declared independence from Russia three years before the shelling of Grozny began in 1994.

While disputes between groups are common, the escalation of these disputes into lethal violence cannot be explained merely by reference to sectarian, ethnic, or cultural background. Indeed, in the Commission's view, mass violence is never "inevitable." Warfare does not simply or naturally emerge out of contentious human interaction. Violent conflict is not simply a tragic flaw in the cultural inheritance and history of certain groups.

Violent conflict results from choice—the choice of leaders and people—and is facilitated through the institutions that bind them. To say that violent clashes will inevitably occur and can only be managed, a view implicit in much of the contemporary literature on mediation and conflict resolution, will not do. 1 The factors that lead to the choice to pursue violence are numerous and complex, and this chapter seeks to illuminate how they emerge. What are the political, economic, and social circumstances that lie behind decisions for violent action? Why do leaders and groups choose deadly conflict? Can anything be done to make them choose differently?

Many of the factors that can lead to violent conflict—between and within states—are in fact sufficiently well understood to be useful in prevention. The causes of war in general and specifically of war in the pre-Cold War period have been well studied. What do these studies suggest about the causes of conflict?

Violent conflict has often resulted from the traditional preoccupation of states to defend, maintain, or extend interests and power. 2 A number of dangerous situations today can be understood in these terms. The newly independent states of the former Soviet Union harbor thinly veiled concerns that Russia's active interest in disputes that lie beyond its present borders may lead to intervention. In the Middle East, much of the maneuvering among the various governments reflects calculated efforts to maximize power and minimize vulnerability. In East and Southeast Asia, some states are wary of their territorial disputes with a resurgent China, fearing that they could become unmanageable. In South Asia, the long festering dispute over Jammu and Kashmir has bedeviled relations between India and Pakistan, impairing the economic and social development of almost one-fifth of humanity. Greece and Turkey have come dangerously close to war several times over the past decades, and border disputes between Ecuador and Peru and Nigeria and Cameroon have led to repeated though relatively minor violence.

Yet, remarkably, no significant interstate wars rage in 1997. Since the end of the Cold War, most states have managed—often with help from outside—to stay back from the brink.

The fact that there are fewer instances of interstate war in the post-Cold War period is remarkable in view of the number and size of states around the world in the throes of profound political, social, and economic transition, especially where large groups of one country's population have close cultural and ethnic ties with another country. In many cases the transition process is painful and protracted and has created a volatile political climate, sometimes because of the absence of established political institutions that have the confidence of the public and the flexibility to absorb the shock of radical changes. Many economies are in disarray, and social cohesion is severely strained.

The absence of major interstate conflict is all the more remarkable given the existence of the many familiar motives that have fueled interstate conflict in the past. Disputes over territory and boundaries, profitable natural resources such as oil or necessities such as water, kindred populations across borders, and the complicating factor of national honor, still chafe relations between neighbors. Yet states now appear to work hard to prevent these continual sources of friction from turning violent. Moreover, as the Cold War recedes, war between or among the most powerful countries appears, for the time being at least, to be unlikely. However, and ironically, as interstate wars wane, violent intrastate conflict has exploded.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Conflict within States

The internal conflicts of the post-Cold War period have involved both states in transition (about a dozen) and established states, many with long histories of internal discord (some 25 in all).

A significant source of conflict is to be found in the competition to fill power vacuums, especially during times of transition within states and often as a result of the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union. 3 During the Cold War, many regimes around the world maintained power through repressive measures made possible by substantial help from major powers on opposite sides of the East-West divide. Powerful states helped maintain these repressive regimes, in part to ensure that the other side in the Cold War did not gain control, and in part to avoid the risk that local conflicts might escalate into a direct confrontation between the superpowers. In Angola, Central America, and the Horn of Africa, for example, the superpowers in effect fought by proxy through local factions. The end of the Cold War eliminated this practice. Unable to maintain a hold on power without massive help from outside, many regimes have found themselves challenged by internal groups, and those challenges have often led to violence.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, more than 50 states have undergone political transformation. 4 Such states may be prone to violence because of the inherent dangers that exist where habits of democratic governance have not yet fully taken hold and where deeply contentious issues of minority status and entitlement remain unsolved. 5 Political alienation can be extremely destructive in such cases.

Other explanations for conflict can be derived from economic factors, such as resource depletion, rising unemployment, or failed fiscal and monetary policies, particularly when discriminatory economic systems create economic disparities along cultural, ethnic, or religious lines. 6 The efforts of some countries to modernize—to become competitive in the global economic system and to meet the needs of growing populations—are often accompanied by cultural clashes started by people wanting to maintain traditional ways of life. Few doubt that economic conditions contribute to the emergence of mass violence, although experts disagree about exactly how the stresses of economic transformation contribute to violent outbreaks.

Outsiders may exacerbate internal conflicts. Neighbors often become involved because of fear of spillover effects (e.g., outflow of refugees or soldiers regrouping), pressure from domestic constituencies, perceived economic interests, or threats to their citizens abroad. Insurgents sometimes are able to entice foreign intervention by appeals to religious and ethnic solidarity, or by using local resources to pay for foreign mercenaries. Intervention can range from supplying weapons and support to direct participation with organized military forces. Turkey has accused Syria of providing financial support and a safe haven for Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) terrorists. Russia is thought by some surrounding countries to have a hand in violence around its periphery. 7 Croatia allowed Iranian arms to go through to the Bosnian government forces—apparently with at least tacit U.S. support—despite the UN arms embargo. Indeed, outside actors play a catalytic role in internal conflict, even if they stand by and do nothing.

At the moment there is no specific international legal provision against internal violence (apart from the Genocide Convention and more general prohibitions contained in international human rights instruments), nor is there any widely accepted principle that it should be prohibited. Yet, the Commission believes that, as a matter of fundamental principle, self-determination claims by national or ethnic communities or other groups should not be pursued by force.

At the moment there is no specific international legal provision against internal violence (apart from the Genocide Convention and more general prohibitions contained in international human rights instruments), nor is there any widely accepted principle that it should be prohibited. Yet, the Commission believes that, as a matter of fundamental principle, self-determination claims by national or ethnic communities or other groups should not be pursued by force.

In other contexts we do recognize that situations can arise where groups within states may, as a last resort, take violent action to resist massive and systematic oppression, in the event that all other efforts, including resort to international human rights machinery, have failed. This is violence in defense of human security—as was the case, for example, in South Africa. This case also illustrates an actively helpful role for the international community in diminishing oppression and paving the way toward nonviolent resolution of underlying problems. The international community should advance this fundamental principle and establish the presumption that recognition of a new state will be denied if accomplished by force.

In summary, the Commission's strong view is that the words "ethnic," "religious," "tribal," or "factional"—important as they may be in intergroup conflict—do not, in most cases, adequately explain why people use massive violence to achieve their goals. These descriptions do not, of themselves, reveal why people would kill each other over their differences. To label a conflict simply as an ethnic war can lead to misguided policy choices by fostering a wrong impression that ethnic, cultural, or religious differences inevitably result in violent conflict and that differences therefore must be suppressed. Time and again in this century, attempts at suppression have too often led to bloodshed, and in case after case, the accommodation of diversity within appropriate constitutional forms has helped prevent bloodshed.

In the Commission's view, mass violence almost invariably results from the deliberately violent response of determined leaders and their groups to a wide range of social, economic, and political conditions that provide the environment for violent conflict, but usually do not independently spawn violence. The interplay of these predisposing conditions and violence-prone leadership offers opportunities for prevention.

Within diverse political, economic, and social environments, many factors heighten the likelihood of violence—political and economic legacies of colonialism or of the Cold War, problematic regional relationships, religious or ethnic differences sustained by systematic cultural discrimination, political or economic repression, illegitimate government institutions, or corrupt or collapsed regimes. Rapid population growth or drastic economic changes generate extreme social and economic frictions, and a shortage of vital resources can also exacerbate feelings of deprivation, alienation, hatred, or fear. Other factors can worsen the situation, including sudden changes of regime, disturbances in neighboring areas, and, as discussed, the ready availability of weapons and ammunition. 8 A dramatic event, such as the plane crash that killed the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi and precipitated the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, can trigger or be used as the pretext for an outbreak of violence. Demagogues and criminal elements can easily exploit such conditions. Indeed, it may be possible to predict violent conflict from some of these factors. For example, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) foresees a high risk for refugee disasters when minority populations are present in economically depressed areas that border kin states. 9

The political interaction between societies and their leaders helps to explain why, under some circumstances, violence breaks out between groups—both within and across state boundaries—and why with other groups in very similar circumstances it does not. Mass violence results when leaders see it as the only way to achieve their political objectives, and they are able to mobilize groups to carry out their strategy. Without determined leaders, groups may riot but they do not start systematic, sustained campaigns of violence to achieve their goals; and without mobilized groups, leaders are unable to organize a fight.

This is not to say that deliberate choices by leaders are the only cause of violence. Miscalculation and unforeseen events also contribute to the outbreak of violent conflict. Nonetheless, the state of mind of leaders is almost always an important factor. Their judgments are usually strongly influenced by two calculations: whether they think that violence will achieve their aims, and whether they think they must use violence to survive. A central question concerns how leaders' interests in pursuing certain objectives—for example, group emancipation, regime change, or self-aggrandizement—develop into pursuing violence to achieve those objectives.

Obviously, not all leaders who turn to violence are evil. Leaders and their followers, seeing their goals to be in direct conflict with those of their opponents, may discern no effective alternatives to violence and believe they can win. 10 And where there are no mediating structures of governance or help from outside that both sides trust, advocates of violence will usually prevail. Sometimes external factors, such as the threat of outside intervention or the effects of the fighting on bordering areas or states, may influence a leader's decisions regarding whether or when to initiate violence. Certainly, domestic circumstances and relationships with followers, as well as with rival leaders, help to explain why violence is chosen, especially when alternative methods of settling a dispute exist. In many cases, particularly in a crisis, leaders may maintain only a tenuous authority and therefore respond to the group demands for action.

These demands and, more broadly, a group's susceptibility to violence, typically develop from a combination of factors. Such factors include conflicting claims and objectives, hatred or fear of others, the conviction that there is no alternative to violence, a sense that the group could prevail in a military contest, and an assessment that fighting will provide better prospects for the future. 11 Yet even when such factors exist, and despite the dire predictions of observers who believe warfare is inevitable, violence does not always arise. Why?

To understand how violence can be avoided even in the context of grave, profound conflict, it is useful to look at transitions where mass violence could have been expected to break out, but did not. The transitions of South Africa and the Soviet Union offer two prominent examples. 12 The striking transformation of these countries in relative peace points out the importance of three factors that might help forestall mass violence: leadership, social cohesion (magnified in a robust civil society that offers a vibrant atmosphere for citizen interaction, or in accepted patterns of civil behavior able to absorb the shocks of rapid change), and concerted international engagement. Later sections of this report will examine these factors in greater detail.

South Africa

South Africa's transition began toward the end of the 1980s and the latter days of P.W. Botha's presidency—a regime marked by some of the most severe repression of the apartheid era.

13

As Communism entered its final phase in Europe and political transformation of the countries of the Warsaw Pact began, the South African government began a secret dialogue with representatives of the African National Congress (ANC). Even among members of the inner circle of the ruling National Party (NP), few realized that a dialogue had begun between Botha himself and Nelson Mandela.

South Africa's transition began toward the end of the 1980s and the latter days of P.W. Botha's presidency—a regime marked by some of the most severe repression of the apartheid era.

13

As Communism entered its final phase in Europe and political transformation of the countries of the Warsaw Pact began, the South African government began a secret dialogue with representatives of the African National Congress (ANC). Even among members of the inner circle of the ruling National Party (NP), few realized that a dialogue had begun between Botha himself and Nelson Mandela.

Mandela met with Botha in the summer of 1989, shortly before the latter's resignation. The dialogue continued with Botha's successor, F.W. de Klerk, and on February 2, 1990, de Klerk announced that Mandela would be released from jail after 27 years. He also lifted the ban on the ANC and other opposition parties. 14 This unexpected move marked the beginning of formal negotiations to move South Africa away from apartheid and toward democracy.

The negotiating process was painstaking, beset with obstacles, and accompanied by periodic outbreaks of political violence. Each stalemate was met by public threats to break off the talks. At crucial moments, help provided by the UN and certain private sector agencies was able to assist in restoring the negotiating process. 15 In November 1993, an interim constitution was adopted, and in 1994, the first open elections in South African history were held. Local elections and the adoption and ratification of a final constitution in 1996 consolidated the new democracy.

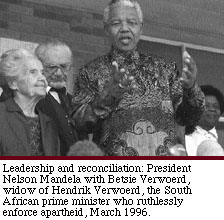

Leadership, civil society, and international engagement account for much of the success—that is, the relative peace—of the transition. Indeed, enlightened leadership on both sides may prove to be the most important factor. For his part, de Klerk did not have full support within his own party. Significant segments of the Afrikaner and English-speaking populations were (and indeed remain) opposed to the process of accommodation with black South Africans. Some elements of the black population contemplated intensifying the armed struggle to defeat fully the old regime. Yet under the extraordinary leadership of Mandela and others, they did not. Mandela's willingness to forgive his captors for his 27-year imprisonment established a tone of national reconciliation.

Moreover, within the black community, an active civil society—trade unions, women's groups, professional organizations, human rights groups, and community-based education programs—provided an opportunity for the development of black leadership, strong social structures, and alternative means of political participation. Many people active in these groups would later assume leadership roles in the ANC-led government. The respect that these leaders gained through years of community activism has helped carry South Africa through its transition.

Finally, black and white South Africans alike acknowledge and credit the importance of concerted international action in pushing the country toward change and in helping that change come about. The controversial economic sanctions imposed by the international community against South Africa in 1979, though incapable of bringing about immediate change, had a cumulative impact on the South African economy and on its leaders. By the end of the 1980s, particularly as financial sanctions impeding the flow of capital to South Africa took greater effect, it was increasingly obvious that sufficient economic growth was impossible without reintegration into the world economy. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and subsequent marginalization of South Africa's position as a self-styled regional bulwark against Communism, it also became evident that reintegration into the global economy would take place only after the integration of South Africa's own society. International sanctions became an important bargaining chip in the negotiation process—a chip the ANC would not finally trade in until late in 1993 when Mandela called for the lifting of all sanctions.

While the international community attempted to weaken the apartheid state, it also worked to build the economic, political, and social resources of the black community. Governments and private organizations contributed millions of dollars to the development of a civil society whose leaders and organizations have contributed so much to the success of South Africa's transition.

Finally, symbolic gestures reinforced the international community's commitment to the creation of a democratic South Africa and encouraged South Africa's leaders to stay on the peaceful path to change. The award of the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize to de Klerk and Mandela, for instance, did more than just recognize the remarkable progress that had been made. In focusing the attention of the international community on South Africa, it strengthened the two leaders in their efforts to conclude final power-sharing agreements. 16

The Soviet Union

Although there were clear signs of decay within the Soviet Union by the early 1980s, few would have predicted that within a decade, Eastern Europe would be free and the Soviet Union itself would dissolve into 15 separate states in a largely nonviolent process. An examination of this historic and relatively peaceful transition reveals that, here too, leadership, social cohesion, and international engagement all played significant roles.

Although there were clear signs of decay within the Soviet Union by the early 1980s, few would have predicted that within a decade, Eastern Europe would be free and the Soviet Union itself would dissolve into 15 separate states in a largely nonviolent process. An examination of this historic and relatively peaceful transition reveals that, here too, leadership, social cohesion, and international engagement all played significant roles.

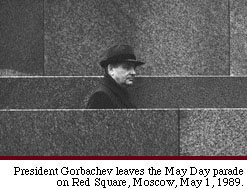

From the time Mikhail Gorbachev embarked on a course of reform in 1985, to the crisis of the attempted coup in August 1991 and beyond, leadership from the Kremlin and the capitals of the newly independent states was essential to the process of peaceful transition. 17 Gorbachev recognized that the economy and society of the Soviet Union, weakened by the decades-long emphasis on military competition with the West and the nature of the totalitarian system, were unsustainable. He set the forces of change in motion and soon learned that he could not control those forces. Widely criticized for his efforts in the years since he left office, Gorbachev nevertheless manifested a strong commitment to effecting a peaceful change and to bringing into practice the values of democracy. His commitment to nonviolence set the tone for the peaceful dissolution of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact. Faced with the prospect of propping up faltering East European Communist regimes by force, Gorbachev broke ranks with his predecessors and elected not to send in troops to preserve the old order.

Gorbachev's turn away from the habit of automatic crackdown may also have influenced events in the remarkably bloodless reversal of the attempted coup of 1991. Although Gorbachev became unpopular in Russia for presiding over the collapse of the Soviet economy and political system, there was no widespread popular support for a return to the old ways. The coup leaders underestimated the power of the unleashed forces of political liberalization. The resounding cry of opposition to the illegal seizure of power from supporters of democratic reform led by Boris Yeltsin—one of Gorbachev's most bitter political rivals—was instrumental in consolidating popular resistance to a return to government-by-force.

Other internal factors in the Soviet Union contributed to the peaceful outcome of these dramatic events. While the institutions and habits of civil society had been repressed during 70 years of totalitarian rule, the seeds of civil society found fertile ground among the highly literate population and the highly developed (although state-dominated) social institutions of the Soviet Union. Labor unions took on a new life and emerging grassroots political and religious organizations became increasingly active and helped provide a measure of organizational stability in the last days of the Soviet Union. As did the newly free press; the independent radio broadcasts from Yeltsin's stronghold at the Russian White House during the coup gave ordinary citizens a different version of events from those that they received from the official television station.

Other internal factors in the Soviet Union contributed to the peaceful outcome of these dramatic events. While the institutions and habits of civil society had been repressed during 70 years of totalitarian rule, the seeds of civil society found fertile ground among the highly literate population and the highly developed (although state-dominated) social institutions of the Soviet Union. Labor unions took on a new life and emerging grassroots political and religious organizations became increasingly active and helped provide a measure of organizational stability in the last days of the Soviet Union. As did the newly free press; the independent radio broadcasts from Yeltsin's stronghold at the Russian White House during the coup gave ordinary citizens a different version of events from those that they received from the official television station.

The international community played a vital role in helping to moderate the Soviet transition. Its broad support gave Gorbachev room to maneuver with respect to the hard-line elements in the Kremlin who might otherwise have been moved to respond more forcefully to hold the country together. An enabling international environment made it possible for reformers inside to argue that Russian security was not being threatened by the unfolding events, leaving little room for extremist voices to gain popular support during the height of political upheaval. 18

These cases illustrate an important point about international engagement. It may be clear in certain cases to those closest to a conflict that international engagement can help avoid mass violence. It is not always clear, however, what outsiders should do or how they can be persuaded to act wisely and in a timely manner.

What Can Be Done? What Are The Tasks? What Works?

Just as in the practice of good medicine, preventing the outbreak, spread, and recurrence of the disease of deadly conflict requires timely interventions with the right mix of political, economic, military, and social instruments. Subsequent chapters of the report will seek to spell out how all these instruments might work.

The circumstances that give rise to violent conflict can usually be foreseen. Early indicators include widespread human rights abuses, increasingly brutal political oppression, inflammatory use of the media, the accumulation of arms, and sometimes, a rash of organized killings. Such developments, especially when combined with chronic deprivation and increasing scarcity of basic necessities, can create an extremely volatile situation. Successful prevention of mass violence will therefore depend on retarding and reversing the development of such circumstances.

The circumstances that give rise to violent conflict can usually be foreseen. Early indicators include widespread human rights abuses, increasingly brutal political oppression, inflammatory use of the media, the accumulation of arms, and sometimes, a rash of organized killings. Such developments, especially when combined with chronic deprivation and increasing scarcity of basic necessities, can create an extremely volatile situation. Successful prevention of mass violence will therefore depend on retarding and reversing the development of such circumstances.

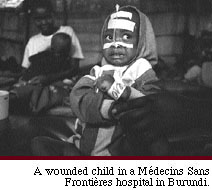

When efforts to forestall conflict do not succeed, it is essential at least to prevent the conflict from spreading. Such efforts include political and diplomatic measures to help manage and resolve the conflict as well as humanitarian operations to relieve victims' suffering. When a cessation of hostilities is achieved, the task of securing peace despite distrust and hatred usually proves to be long, frustrating, and expensive, but it is essential in order to break the cycle of violence.

A further important element in this equation, particularly in the context of avoiding conflict between states, is the development of effective international regimes for arms control and disarmament, for rule making and dispute resolution, and for dialogue and cooperation more generally. All of these can be important in preventing disagreements or disputes from escalating into armed conflict.

The preventive needs identified above involve avoiding the outbreak, escalation, or recurrence of mass violence. It is difficult in practice, however, to develop effective policies merely of avoidance. It may therefore be more useful to think of prevention not simply as the avoidance of undesirable outcomes but also as the creation of preferred circumstances. This approach was one of the basic strategies of the Marshall Plan and other economic and political initiatives in Europe after World War II: to build capable and self-reliant partners within Europe, to strengthen relations between Europe and North America, and to reduce tensions between former adversaries and integrate them into a more cohesive political and economic community. A similar effort was undertaken with respect to Japan. The countries devastated by war needed to become flourishing societies for their own future peace and benefit, and in so doing, they would become more able to withstand the pressures of totalitarianism, both internally and externally.

To move policies of prevention toward greater pragmatic effect, therefore, the broad objectives identified above might be stated more fully as:

Promote effective international regimes—for arms control and disarmament, for economic cooperation, for rule making and dispute resolution, and for dialogue and cooperative problem solving.

Promote stable and viable countries—thriving states with political systems characterized by representative government, the rule of law, open economies with social safety nets, and robust civil societies.

Create barriers to the spread of conflict within and between societies—by means such as the suffocation of violence through various forms of sanctions (including the denial of weaponry and ammunition, or restricting access to the hard currency resources necessary to fund continued fighting), the preventive deployment of military resources when necessary, and the provision of humanitarian assistance to innocent victims.

Create a safe and secure environment in the aftermath of conflict by providing the necessary security for government to function, establishing mechanisms for reconciliation, enabling essential economic, social, and humanitarian needs to be met, establishing an effective and legitimate political and judicial system, and regenerating economic activity.

Strategies for prevention fall into two broad categories: operational prevention (measures applicable in the face of immediate crisis) and structural prevention (measures to ensure that crises do not arise in the first place or, if they do, that they do not recur). The following chapters develop these strategies and offer a view as to how governments, international organizations, and the various institutions of civil society might best help implement them.

Notes

Note 1: See, for example, Edward E. Azar and John W. Burton, eds., International Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice (Sussex: Wheatsheaf Books, 1986); Robert O. Matthews, Arthur G. Rubinoff, and Janice Gross Stein, eds., International Conflict and Conflict Management: Readings in World Politics (Scarborough, Ontario: Prentice-Hall Canada, Inc., 1989); John W. McDonald, Jr., and Diane B. Bendahmane, eds., Conflict Resolution: Track Two Diplomacy (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1987); Joseph V. Montville, ed., Conflict and Peacemaking in Multiethnic Societies (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1990); Jack Nusan Porter, Conflict and Conflict Resolution: A Historical Bibliography (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1982); Leif Ohlsson, ed., Case Studies of Regional Conflicts and Conflict Resolution (Gothenburg, Sweden: Padrigu Papers, 1989); Ramesh Thakur, ed., International Conflict Resolution (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1988). Back.

Note 2: Robert Gilpin, War and Change in World Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1981); George F. Kennan, Realities of American Foreign Policy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1954); Henry A. Kissinger, A World Restored (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1964); Hans J. Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations (New York: Knopf, 1948); Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1979); Mohammed Ayoob, "The New-Old Disorder in the Third World," in The United Nations and Civil Wars, ed., Thomas G. Weiss (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1995), pp. 13-30. Back.

Note 3: Mark Katz, "Collapsed Empires," in Managing Global Chaos, eds., Chester A. Crocker and Fen Osler Hampson, with Pamela Aall (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1996), pp. 25-35. Back.

Note 4: These countries moved toward democratic rule through transitional elections. See Roger Kaplan, Freedom in the World (New York: Freedom House, 1996), pp. 105-107. Back.

Note 5: Edward D. Mansfield and Jack Snyder are among those who argue that states in transition to democracy are prone to conflict. Edward D. Mansfield and Jack Snyder, "Democratization and the Danger of War," International Security 20, No. 1 (Summer 1995), pp. 5-38. For criticisms of their argument, see "Correspondence," International Security 20, No. 4 (Spring 1996), pp. 176-207. The scholarly debate over the democratic peace proposition is captured in a selection of essays presenting both sides of the issue; see Michael E. Brown, Sean M. Lynn-Jones, and Steven E. Miller, eds., Debating the Democratic Peace (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996). See also the discussion of this subject in chapter 4. Back.

Note 6: Richard E. Bissell, "The Resource Dimension of International Conflict," in Managing Global Chaos, eds., Chester A. Crocker and Fen Osler Hampson, with Pamela Aall (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1996), pp. 141-153; Naomi Chazan and Donald Rothchild, "The Political Repercussions of Economic Malaise," in Hemmed In: Responses to Africa's Economic Decline, eds., Thomas M. Callaghy and John Ravenhill (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), pp. 180-214; Gareth Porter, "Environmental Security as a National Security Issue," Current History 94, No. 592 (May 1995), pp. 218-222; David A. Lake and Donald Rothchild, "Ethnic Fears and Global Engagement: The International Spread and Management of Ethnic Conflict," Policy Paper #20, Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation, San Diego, CA, January 1996. Back.

Note 7: Articles from regional newspapers illustrate the concern of states with internal strife that outside actors are attempting to influence the outcome of events. Turkish president Suleyman Demirel has accused Syria of supporting the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK): "Syria's support for the PKK is clearly evident...it not only supports the PKK, but actively supports all the other organizations that want to change the regime in Turkey." (Makram Muhammad Ahmad, "Turkey: Demirel on Ties With Syria, Terrorism," Al-Musawwar, July 26, 1996, pp. 18-21, 82-83.) Typical of many states of the former Soviet Union, Georgian denunciation of Russian aid and support for the Abkhaz rebels reflects anger over Moscow's perceived double standard policy for its "near abroad." ("Anti-Russian 'Hysteria' Over Abkhazia in Georgia," Pravda, July 13, 1995, p. 1.) Back.

Note 8: The development of conflict indicators for crises within states is a new field with much experimentation. For example, Pauline Baker and John Ausink identify the following indicators of potential internal strife: demographic pressures, massive refugee movements, uneven economic development along ethnic lines, a legacy of vengeance-seeking behavior, criminalization, and suspension of the rule of law. Pauline H. Baker and John A. Ausink, "State Collapse and Ethnic Violence: Toward a Predictive Model," Parameters 26, No. 1 (Spring 1996), pp. 19-31. A study by Michael Brown identifies both underlying and proximate causes of internal conflict (see Table N.1). Additionally, the Organization of African Unity (OAU) is developing a Conflict Management Division and an extensive list of early warning indicators. Back.

|

Note 9: Personal communication, Irene Khan, Chief of Mission, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees—New Delhi, April 17, 1995. Back.

Note 10: Jack S. Levy, "Prospect Theory and International Relations: Theoretical Applications and Analytical Problems," in Avoiding Losses/Taking Risks: Prospect Theory and International Conflict, ed. Barbara Farnham (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), pp. 119-145. Back.

Note 11: "Susceptibility" here does not mean being unwitting, but rather "open" or disposed (for many reasons) to follow leadership in this direction. In fact, whole societies or groups do not have to go along, only some critical part—armies or some groups of those willing to fight. Conversely, various factors can inhibit the willingness of a group to be led to initiate conflict, such as physical dispersion, widespread prosperity or even pervasive poverty, war weariness, or indifference to the issues said to be at stake. This analysis builds on the work of Dean G. Pruitt and Jeffrey Z. Rubin, Social Conflict: Escalation, Stalemate, and Settlement (New York: Random House, 1986). Back.

Note 12: Other examples include Benin, Eritrea, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and the breakup of Czechoslovakia into the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Back.

Note 13: As disclosures now bring to light, even the highest levels of Afrikaner leadership may have been actively engaged in the violent, clandestine counterinsurgency efforts aimed at breaking resistance to the apartheid regime. "'Prime Evil' de Kock Names Ex-President Botha, Cabinet Ministers, Police Generals in 'Dirty War,'" Southern Africa Report 14, No. 38 (September 20, 1996). For an in-depth treatment of the earliest meetings between National Party officials and opposition leaders, see Allister Sparks, Tomorrow Is Another Country: The Inside Story of South Africa's Road to Change (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995). Back.

Note 14: Jack Reed, "De Klerk Lifts ANC Ban, Says Mandela Will be Freed Soon," United Press International, February 2, 1990; Timothy D. Sisk, Democratization in South Africa: The Elusive Social Contract (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), pp. 83-84. Back.

Note 15: In 1986, a privately funded study commission on U.S. policy toward South Africa, chaired by Franklin A. Thomas, facilitated initial contacts between ANC leaders and prominent Afrikaners with close ties to the apartheid government. These contacts helped open the way for the crucial political dialogue which followed. Allister Sparks, Tomorrow Is Another Country: The Inside Story of South Africa's Road to Change (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995), pp. 72-73. Back.

Note 16: For detailed discussions of South Africa's transition, see David Ottaway, Chained Together (New York: Times Books, 1993); Marina Ottaway, South Africa (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 1993); Timothy D. Sisk, Democratization in South Africa: The Elusive Social Contract (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995); Patti Waldmeir, Anatomy of a Miracle: The End of Apartheid and the Birth of the New South Africa (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1997). See also John Stremlau with Helen Zille, A House No Longer Divided: Progress and Prospects for Democratic Peace in South Africa, (Washington, DC: Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict, July 1997). Back.

Note 17: Some analysts argue that although the term "perestroika" was used in 1985, real reform did not begin until 1986. Others, however, assert that Gorbachev's 1985 personnel changes, which moved reformers into positions of power, constitute the beginnings of reform. Gorbachev sets the beginning of reform as early as 1985; in Perestroika, he states that reform had been under way for two and one-half years. Mikhail Gorbachev, Perestroika: New Thinking for Our Country and the World (New York: Harper and Row, 1987), p. 60; Seweryn Bialer, "The Changing Soviet Political System: The Nineteenth Party Conference and After" in Politics, Society and Nationality Inside Gorbachev's Russia, ed., Seweryn Bialer (Boulder: Westview Press, 1989), pp. 193-241. See also Jack F. Matlock, Jr., Autopsy on an Empire: The American Ambassador's Account of the Collapse of the Soviet Union (New York: Random House, 1995), pp. 52-67. Back.

Note 18: The West's negotiation strategy in concluding the November 1990 Two + Four Agreement, which laid the framework for German reunification, was instrumental in assuaging Russian security fears. For further reading, see Michael Beschloss and Strobe Talbott, At the Highest Levels: The Inside Story of the End of the Cold War (Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1993), pp. 184-190; Mikhail Gorbachev, Memoirs (New York: Doubleday, 1996), especially pp. 527-535; Philip Zelikow and Condoleezza Rice, Germany Unified and Europe Transformed: A Study in Statecraft (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), pp. 149-197, 328-352. Back.