|

|

|

|

Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey

University of Washington Press

1997

11. Silent Interruptions: Urban Encounters with Rural Turkey

The architecture of rural Turkey has been a recurrent theme in the grand narrative of modern Turkish architecture. It was captured by a wave of nationalist and regionalist interests in the 1930s and early 1940s, valued by disappointed modernists in the 1960s, and rediscovered for its consumptive value in the 1980s. In the earlier phases, the proponents of regionalism had to draw careful distinctions between an ideal, sanitized, and immaculate rural imaginary and the unenviable state of real Turkish villages. Paradoxically perhaps, the rural imaginary privileged the model of an ideal, clean, orderly city and used it as a cultural and physical exemplar. 1 The impossibility of realizing this impeccable model became apparent after the unprecedented urban migrations of the 1950s onward—articulated with other social, political, and economic forces beyond the scope of this essay—which threatened the sanitized, controllable, and homogeneous urban vision of the republic’s early leaders. The material effects of this process remain at the core of contemporary cultural studies in Turkey. Opinions are divided. While some lament the phenomenon, interpreting it as the evaporation of the last hopes of the Kemalist vision of cultural modernity, others celebrate it as a much desired plurality that strikes the final blow to homogenizing, elitist, and sterile attempts to create culture from above. 2

This essay is written from a position calling for the opening up of a third space that neither authorizes “one” nor privileges “many.” It attempts to uncover a cultural-architectural space of difference that disrupts preconstructed identities and essences, contesting plurality as a multiplication of sociological totalities; a space in which both essentialist constructions and relativist celebrations are avoided; a space of translation across the urban-rural boundaries set up by the nation’s founding fathers.

Translation, as Walter Benjamin put it, “instead of making itself similar to the meaning of the original, must lovingly and in detail form itself according to the manner of meaning of the original, to make them both recognisable as the broken fragments of the greater language.” 3 Although Benjamin’s description concerns languages, which is somewhat different from my interest here, I find it useful for the framework of my analysis because it recognizes both fluidity and difference. I believe that the cultural border between the city and the village, which architectural discourse has sharply delineated, is a fluid one. Both acknowledgment and repression of difference is made possible by this fluidity. My position calls for the recognition of negotiations without surmounting the space of incommensurable meanings and judgments.

Such spaces of negotiation have hitherto been excluded from or silenced by dominant modes of architectural discourse and practice. Architectural (re)constructions of rural Turkey have long been dominated by worn-out discussions of regionalism and contextualism that take place on a highly prescriptive plane and help perpetuate the status quo. Through sophisticated processes of aestheticization and legitimation, architectural discourse in Turkey has repressed and domesticated its “rural” component by reducing it to building forms. I argue that this repression can be overcome by recognizing the irreducibility of space to form and acknowledging connections between architectural and cultural production.

My aim, however, is neither to undertake a detailed historiographical critique of modern Turkish architecture nor to extend its historical breadth by introducing new and unexplored topics. I am interested, instead, in highlighting particular cultural, historiographical, architectural, and urban moments to generate possible critical openings for present practices of writing and building. In what follows, I analyze three such instances in the spatial history of Ankara in order to explore a possible dialogue at the intersections between urban and rural cultures. My argument flows between textual, architectural, and urban spaces and attempts to engage these with cultural production. All three instances are particular readings of urban scenes that reveal possibilities for erasing ideological constructions of harmonious cultural totalities; they disrupt, betray, and subvert homogenizing tendencies.

Beyond the Monumental Narrative of Urban Space

In urbanistic terms, the planning of the capital city of Ankara is an unsurpassed example of the monumental narrative of modern Turkey. It is also one of the exemplary sites of the relative success and unforeseen failure of the Turkish modernists’ attempts to transcend the inherent contradictions between urban and rural cultural landscapes. The creation of the modern capital from a small central Anatolian town is well known. 4 What is often overlooked is that from the early days of the capital’s foundation, encounters between old (traditional, rural) and new (modern, urban) Ankara engendered significant tensions that disrupted the proper image of the city. I believe these encounters help reveal not one but multiple layers of architectural and urban space, and they enable us to imagine other spatial stories beyond pedagogical narratives. 5

Herman Jansen, the German urban planner of Ankara, mapped the modern capital along two major axes, Gazi Boulevard and Istasyon Avenue, which intersected at a T-junction adorned by a monumental statue of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish republic. These Haussmanian arteries were symbolic connections, the meanings of which far surpassed their function as traffic regulators. Gazi Boulevard, on the north-south axis, marked the direction along which the new city developed. Istasyon Avenue connected the railway station to the boulevard and, in a somewhat less definitive manner, continued east to reach the outskirts of the citadel. The station building was a historical landmark that hosted Mustafa Kemal during the War of Independence. It was the “gateway” to the city.

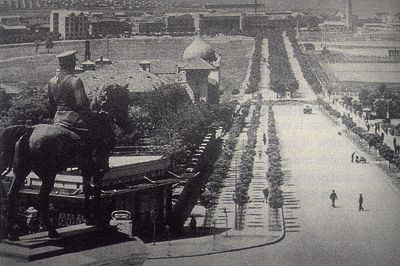

By 1928, Istasyon avenue was lined on both sides by such key buildings as the National Assembly, the Ankara Palas Hotel, and housing for bureaucrats; it was paved and widened to incorporate two lanes separated by a green strip and delineated by regular rows of trees. From the gates of the railway station it was a powerful physical connection to Gazi Boulevard that led the newcomer into modern Ankara. The pride taken in Istasyon Avenue is best reflected in the numerous period photographs that offer a variety of impressive perspectives from all angles (fig. 11.1). The ornamental facades facing Istasyon Avenue that led to the monumental statue of Atatürk were set against the picturesque backdrop of the castellated walls of the citadel. “The extraordinary view of the citadel and its timber framed houses,” as Jansen described it, was carefully preserved for the visual consumption of the modern city. 6 “In new town planning practices,” stated Jansen, “the new sections of the town should be clearly separated from the old. Theoretically, the old town should be covered by a bell jar [emphasis mine].” 7 The astounding metaphor of the bell jar summarized the monumental narrative of modern Ankara that silenced “other” narratives in its own interest.

|

| 11.1. Istasyon Avenue, view toward the railway station, 1936. (Reproduced from Ankara, Turkish Ministry of Culture, 1991.) |

Most importantly for my argument, the monumental narrative often overlooks the fact that the very boulevards that distanced the old city from the new were also connections enabling the flow between them. Some significant instances reveal the ways in which inhabitants of old and new Ankara enacted these urban spaces and made local sense out of the city that was shaped for them. In a much-quoted episode narrated by a leading Turkish intellectual, Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoglu, in his reknowned novel Ankara, inhabitants of old Ankara have gathered on New Year’s Eve outside the monumental entrance of the Ankara Palas hotel on Istasyon Avenue to watch the elite arrive at the ballroom. They engage in the following conversation:

“So you think you have seen it all from here, hah, hah,” one says to another, who replies with a grin, “I know what they do inside, but I won’t say it.” “I will,” interferes a third, “there is tango inside.” “Who is tango?” asks another.

And the conversation continues along these lines as modern Ankara flows into the ballroom and police try to control the entrance. 8

I am intrigued by the striking similarity of Yakup Kadri’s story to Baudelaire’s “The Eyes of the Poor,” which depicts an encounter between two lovers and a poor family in front of a cafe on a new boulevard in 1850s Paris. 9 Istasyon Avenue functioned, on a much smaller scale, like the boulevards designed by Haussmann for Paris in creating a new basis for drawing the different strata of the urban population together. The boulevards, as Marshall Berman articulated it, surfaced the contradictory effects of modern culture. On one hand, they had an unprecedented liberating effect in enabling new forms of privacy within the anonymity of the public—intense forms of self-discovery, dreamy and magical experiences. On the other hand, they highlighted disturbing social and cultural differences and revealed insurmountable communication gaps. In Berman’s words, Baudelaire’s story “shows us how the contradictions that animate the modern city street resonate in the inner life of the man on the street.” 10

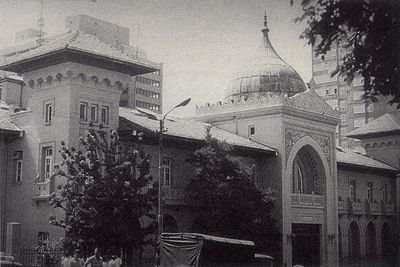

In the doubly complicated Turkish scene, where the liberation of the self is bracketed by the liberation of the nation, and where modern culture is imposed from above, Yakup Kadri seeks a nationalist synthesis to surmount difference. Yet the episode he narrates enables us to see multiple layers of meaning in both Istasyon Avenue and the Ankara Palas, beyond the conventional accounts of architectural or urban history. The Ankara Palas, for example, can no longer be sufficiently described as an excellent example of the First National Movement (fig. 11.2). Any history of the building would be incomplete without mentioning the “production” of the interior space by mechanisms of control, the gaze of those who are denied entry, and the power of these outsiders’ imaginations.

|

| 11.2. Facade of the Ankara Palas. Architects Vedat Tek and Kemalettin Bey, 1924–27. (Photograph by the author.) |

The narrative multiplies when we cross the physical boundary and realize that the people who populated the ballroom enacted a cultural space that rendered them as ambivalent as their voyeurs outside. For the privileged inhabitants of Ankara, dressed elegantly in accordance with the fashion pages of local newspapers that brought the latest news from Paris, and having adopted appropriate codes of behavior based on how-to books on “modern manners,” ballroom dancing was part of a performance that they rehearsed only ambivalently. At a gathering to celebrate the anniversary of the republic, Mustafa Kemal is said to have called the reluctant women to the dance floor this way: “I cannot imagine a woman who can possibly reject the dance proposal of a Turkish man in his military uniform. Now I command: To the dance floor! Forward! March! Dance!” 11 The astounding military, nationalist, and sexist tone of the command reflected the contradictions in the construction of a monolithic modern culture imagined by the founders of the republic. One wonders whether it was the citadel or the Ankara Palas hotel that was covered by a bell jar.

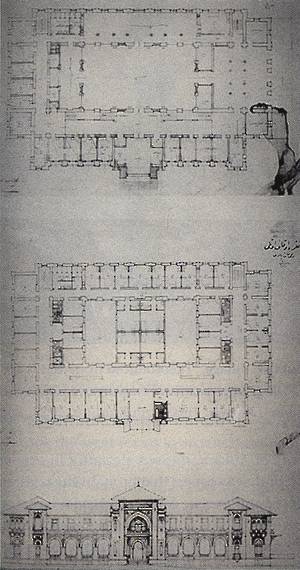

A standard source on modern Turkish architecture describes the Ankara Palas as “a two storey, rectangular building with a great ballroom at the center, reminiscent of the historical Ottoman inns with central courtyards surrounded by guest rooms on two floors” (fig. 11.3). 12 If the architect was indeed inspired by the Ottoman inns, the irony of the inversion of the function of the central courtyard from that of a functionally inclusive space (all travelers are welcome) to that of a culturally exclusive space cannot be overlooked. Noting the fluidity of the way the central hall opens to the surrounding spaces, I believe that further research may reveal other forms of control and boundary (such as gender-based ones) no less significant and complex than those symbolically embedded in the monumental entry. The architectural literature on Ankara Palas that comfortably locates it in the First National Movement and describes solely its formal composition and spatial inspiration powerfully forecloses alternative ways of understanding the complexities of the architectural and urban space it has generated.

|

| 11.3. Original ground-floor plan of the Ankara Palas. (Reproduced from Renata Holod and Ahmet Evin, eds., Modern Turkish Architecture, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984, 55.) |

To summarize, the sanitized monumental architectural and urban spaces of modern Ankara attempted to guard the proper image of the new city. The practice of everyday life, however, insidiously disrupted the grand narrative by bringing to the surface meanings and values that were generated in between the cultural and spatial boundaries the city fathers delineated with utmost care.

Same Words, Different Languages

The relationship between the modern Turkish city and its “other”—that is, rural Turkey—took different forms in architectural discourse and practice. Much has already been written about the architectural appropriation of rural vernacular forms and the civilizing mission of Turkish architects in rural areas. I will briefly summarize some relevant points before continuing my discussion of spatial and architectural interruptions.

Typological studies of the Turkish house and the enthusiastic assimilation of rural forms in urban buildings have been recurrent obsessions in architectural circles since the 1930s. At that time, extensive academic work was based on rigorous research on the house types of various geographical regions. Many urban residences boasted such features as projected roofs or centralized plans based on vernacular examples. Much of the research was carried out in conjunction with intense debates over the appropriate choice between regionalism and modernism. This discourse was evidently located within a larger cultural discourse that sought to synthesize culture and civilization to project a modern Turkish identity. As a survey of architectural journals from this period shows, debates among Turkish architects often came to a standstill when belief in the inevitable Turkishness of modern architecture converged with a conviction about the essential modernity of the Turkish vernacular. 13

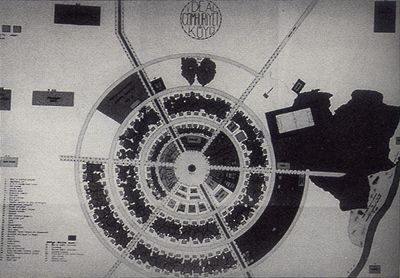

Along with the assimilation of rural forms by leading Turkish architects, the 1930s and early 1940s saw unprecedented efforts to accumulate and systematize rural data and to realize the republic’s civilizing mission in rural settlements. In architecture, these attempts yielded a series of ideal types, both built and unbuilt, ranging from model villages to individual houses. These were inspired by a host of Western examples, including German Siedlungen and existenzminimum housing principles. 14 Model villages consisted of neatly arranged rows of identical houses reminiscent of the disciplinary environments of nineteenth-century factory towns. Typical rural houses were miniaturized versions of urban apartments. I was astounded to find the plan of “An Ideal Turkish Village” appended to a 1933 publication of the Turkish Historical Society (fig. 11.4). 15 Unmistakably inspired by Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City, the centralized plan for the ideal village consisted of clearly demarcated zones for sports, health and educational facilities, commerce, and even industry.

|

| 11.4. “An Ideal Turkish Village.” (Reproduced from Afet Inan, Devletçilik Ilkesi ve Birinci Sanayi Plani [The principle of etatism and the first industrial plan of the Turkish republic], Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1933, appendix.) |

I believe these two positions—assimilation of rural elements in urban environments and the use of urban models in rural settings—are in fact one. Both search for a center, ultimately a nationalist core, in which to dissolve all forms of difference. This marks the desire for a moment of transcendence when the nostalgia for lost origins and the demand to civilize reveal themselves as two sides of the same coin. By reducing complex differences to conveniently formulated binary opposites of urban versus rural, traditional versus modern, and regional versus international, these positions refuse to see the complexity that emerges from the gap between fluctuating feelings of fascination and contempt for the rural Turkey they relentlessly homogenized. It seems important, then, to question what they did not say or what they refused to say by working with and through their work and by asking questions from the margins of their powerful claims.

Amidst the mostly unified voices of the humanistic project of the civilizing missioners who visited numerous villages during the 1930s, there were a few that disturbed the tone of the dominant discourse to a significant extent. 16 I refer to two articles by Nusret Köymen, a prolific writer, that appeared in Ülkü, the official journal of Halkevleri (People’s Houses). 17 These articles were important not only for their uniqueness in voicing an alternative opinion in a largely univocal journal but also for reflecting on some critical issues in a sophisticated manner. Köymen pointed out two fundamental difficulties in carrying out the civilizing mission in rural Turkey. First, on a pragmatic level, he believed that given the extremely limited resources of many of these efforts, even the most agreeable ones, those involving issues like health education and technical support, were bound to remain partial and short-lived. Second, and more significant for my argument, he pointed out a fundamental incommensurability between urban and rural cultural practices. An insightful paragraph offers the following observation:

The languages of the urban dweller and the peasant are different even if they use the same words; [they are different] to such an extent that a peasant from a village who has had no contact with any city and an urban dweller who has had no previous rural exposure cannot possibly understand each other.... There is no way to cancel this difference.... The thing for the village reformer [köycü] to do is... to make use of those instances when the peasant’s personality is temporarily split to make room for penetration to influence him. Those are the times when the peasant is in the city. [Emphases mine.] 18

In the village, the author continues, because there is no possibility of communication, peasants do not speak to the reformers. They “merely nod” at whatever they hear.

In its recognition of the incommensurability of the two voices, the peasants’ and the reformers’, Köymen’s position differs fundamentally from that of his contemporaries. He observes that the peasants, vis-à-vis the village reformers, have no voice. They are silenced. They merely nod. Recognizing the opaqueness of language, Köymen refuses to fill the silence with his own voice. Yet that refusal is only momentary. He is not prepared to resign. Once the peasant comes to the city, he notes, again with astonishing insight, his personality is split—that is, he is decentered through his exposure to a second symbolic order, which makes room for intervention. The reformer should use the opportunity to filter through the gap that is created in the process of decentering.

At this stage Köymen calls upon architecture for help. He notes that peasants come to the cities mostly on a temporary basis to settle bureaucratic or administrative matters. Believing in the necessity of gathering the temporary rural population in one center, he suggests building “peasants’ inns.” These, he continues, should be made with regional materials and “according to architectural principles that have been developed through thousands of years of experience.” By mimicking the familiar, the exterior of the building would call upon the peasants’ yearning for home. The interior, on the other hand, should be furnished with easy-to-make objects in a manner that would arouse the peasants’ “civilizing need.” Hence the standard process is reversed: instead of going to the village, the reformer remains in the city to carry out the civilizing mission. As one architect put it in a slightly different context, this meant to “introduce beds to those who are used to sleeping together on earthen floors, to teach those who sit on the floor how to use chairs, to provide tables for those who eat on the floors, to revolutionize lifestyles. [emphasis mine].” 19

Köymen’s idea of peasants’ inns was never realized. It is difficult for me to agree with his agenda, and it seems to me that Köymen was too easily convinced that the peasant in the city would take myth for language. 20 Ironically, a few decades later, his kind of architectural myth (the sanitized facades of the vernacular) would be readily consumed by the urban bourgeoisie in the form of holiday villages in the countryside rather than peasants’ inns in the city. Besides his pointed analysis of the peasant’s subjectivity, what should not be overlooked in Köymen’s call is the feeling of urgency to do something about the peasant in the city. Lurking behind his proposal is the realization that the peasant’s split personality might engender the unknown. If the split was not sealed and surmounted by the pedagogy of the reformers, unknown and intolerable forms of expression might emerge. Indeed, Turkish cities faced this challenge after the late 1940s, when the peasants came to stay.

Limits of (In)tolerance

When the peasants came to stay in Ankara and other major Turkish cities in the late 1940s, there were no peasants’ inns to welcome them. The early stages of migration saw the erection of a few shacks that sporadically spotted the city. Then they multiplied. Between 1937 and 1950 their numbers in Ankara increased from 20,000 to 100,000. 21 At that time the migrants’ labor was only marginal in the economy. Ankara had neither organized industrial accumulation nor widespread small industries to employ them. Hence the migrants settled in areas that were close to the business center but were also topographical thresholds such as steep slopes and areas threatened by landslides and floods (see fig. 9.4).

The new urban phenomenon disturbed the city fathers. In the late 1930s, the Ministry of Interior Affairs assured the “citizens” that Ankara would be cleared of “these unsightly places with miserable roads.” 22 The following decades saw the development of a series of economic and political agendas layered over the issue of rural migrants that lies beyond the scope of this essay. As John Berger says of migrant workers in A Seventh Man,

his migration is like an event in a dream dreamt by another. As a figure in a dream dreamt by an unknown sleeper, he appears to act autonomously, at times unexpectedly; but everything he does—unless he revolts—is determined by the needs of the dreamer’s mind. Abandon the metaphor. The migrant’s intentionality is permeated by historical necessities of which neither he nor anybody he meets is aware. That is why it is as if his life were being dreamt by another.” 23

Although there is no point in denying the power of the dreamer, I believe the autonomous and unexpected acts of the migrant deserve more attention than they have received so far. They have displayed the potential to disrupt historical constructions of Turkish architecture, on one hand, and homogenizing accounts of rural forms, on the other. From an architectural viewpoint, unlike most other buildings, the squatter’s house, known as a gecekondu, is not built on the premise of permanence; it is under continuous threat of demolition. Thus the survival of the early gecekondu dwellings was enabled by their inhabitants’ tactical operations against the relentless strategies of the city fathers.

Strategies, Michel de Certeau proposes, are calculative, rationalized, and manipulative operations of control from positions of power. 24 Strategic rationalizations distinguish and demarcate their own space in an environment “in an effort to delimit one’s own place in a world bewitched by the invisible powers of the Other.” Tactics, on the other hand, are calculated actions “determined by the absence of a proper locus.” Both required and produced by strategies, the de-privileged subjects of tactical operations have no place. They utilize a land that belongs to others. Tactics require a clever use of time. They are ingenious ways in which the weak turn events into opportunities and make use of the strong, and they “thus lend a political dimension to everyday practices.” The architecture and landscape of the early gecekondu areas display ingenious tactics of determined survival.

Here I would like to propose a reading of these areas different from those which described them as “ugly” and “unsightly” and viewed them as “the city’s garbage to be disposed of.” As these descriptions recognized in a rather negative manner, the gecekondu neighborhoods rendered the city opaque. They threatened the transparency of the boulevards that had been proudly described as “the mirror of a beautiful and clean city.” The snaking pathways of the gecekondu areas stood in shameful opposition to the straight axes of modern Ankara. A 1949 newspaper essay on Altindag—one of the earliest hillside gecekondu settlements in Ankara—likened the street network to a maze. It was “like solving a child’s puzzle,” the author wrote, “where you have to find the exit by tracing the correct path within a jumble of lines.” 25

The mazelike pathways were indeed a challenge to the panoptical transparency of the boulevards. Yet they made possible a kind of countercontrol and surveillance on the part of the inhabitants. The opacity of the maze enabled an entire neighborhood network of communication that was vocal and gestural rather than visual. Once that network was activated, news of an intruder reached all the way to the summit within a matter of minutes. One gecekondu dweller, a woman, recounted:

We received the news that the demolishers had arrived, with the police. We didn’t know what to do. Our neighbors advised us. We locked our little kids inside, we remained out of sight. The police came to the house: “Vacate the house, we will demolish.” The kids were all alone inside; they got scared, they started crying and screaming. The police are the police but they are not heartless.... They left when they heard the children’s cries. Since that day, whenever the demolishers come we lock our kids inside and hide away.... This house that you see here has never been demolished. 26

In the late 1940s, one widespread method of constructing gecekondu dwellings in Ankara was as follows: Eight wooden posts were joined in pairs by scrap wood pieces to form four wall panels on the ground, which were then plastered with mud. Rectangular openings were left in two of the panels for a door and a window, respectively. When night fell, these panels were anchored to the ground at four corners and the exterior was covered with scrap metal. When city authorities came to demolish this “house of cards,” all they had to do was push one of the walls for the entire structure to collapse. Yet it was, of course, simple to reerect the panels very quickly. Some such “homes” were rebuilt as many as eleven times. 27 The uncanny repetition of this process is brilliantly captured in Latife Tekin’s novel Berci Kristin: Tales from the Garbage Hills, in which, upon their umpteenth arrival at the same site, the demolishers see only a little girl playing house with a tiny shack she has made from the remains of demolished gecekondus surrounding her. They leave the place, never to show up again. 28

In developing their tactics, rural migrants responded less to such regionalist concerns as climate and topography than to the very conditions that simultaneously affirmed and denied their urban existence. In doing so, they did not necessarily discard ages of accumulated experience from the countryside. In one of the most striking examples in late 1940s Ankara, dwellings were carved into the sloping ground between two roads leading to a hilltop. The only markers of these houses above ground were upside-down earthen pots with holes in their bottoms that, as journalist Adviye Fenik put it, “function[ed] as windows as well as chimneys.” 29

Fenik wrote a series of articles in 1949 on the Altindag gecekondu district in Ankara. Amid many statistical, economical, and administrative analyses of the early gecekondu settlements, hers is the only account I know of concerning everyday life. It is invaluable in providing insights into the tactical operations of gecekondu environments. Fenik’s description of the earthen pots follows her story of how, upon stumbling on one of them, she was asked to step aside because she was “walking on the roof.” Stepping back, she felt as if she had “stepped on a grave.” “Grave” is a chilling metaphor for a house, something I would like to dwell on in relation to another architectural moment that took place less than two decades before Fenik’s encounter with the carved gecekondus.

In 1933, Abdullah Ziya, an architect with the Ministry of Education, made a regional classification of rural buildings in Anatolia. 30 The only category for which he had no word of praise was what he called “negative villages,” where houses were carved into rocky mountains. “When you look at these villages from afar,” he reported, “you see numerous bodies wiggling in the cavities of the slope.” Apparently unimpressed, he decided that since the negative villages did “not have any formal or aesthetic value,” he did “not find it necessary to write about them at length.”

It appears that “negative” dwellings were denied existence in legitimate discourse whether they were located in the city or in the countryside. Their inhabitants were likened to dead bodies (“I felt as if I stepped on a grave”) or to nonhumans (“bodies wiggling in the cavities of the slope”). Topographical and climatic necessities might have generated the negative villages in the first place. Abdullah Ziya’s acknowledgment of built form for its visibility and construction, however, caused him to fail to comprehend carved settlements as architecture. In the city, the carved gecekondus served rural immigrants in a number of vital ways. Besides defying the conventional meaning of urban lot, they were inexpensive to build, difficult to notice, and, most importantly, almost impossible to demolish.

The tactics of the rural migrants displayed the fluidity of architectural and other languages. They did not polarize cultural entities, nor did they attempt to fix meanings. Although it may have no direct bearing on architecture per se, I am tempted to relate one instance in which Quran cases on the walls of gecekondu dwellings contained carefully folded doctors’ prescriptions. The sick were taken to the doctor, but there was no money to buy the prescribed medicine. A traditional healer was called in to cure the patients. The prescription, however, was treasured as “the passport to heaven” and kept inside the Quran case. 31 The intriguing inversion here seems particularly relevant now, when the medical profession itself takes traditional healing methods seriously.

In architectural terms, the gecekondu buildings and settlements interrupt the conventional meanings of such terms as boundaries and walls, inside and outside, and public and private. First, they defy mapping because their size keeps changing. A unit with one room and a detached toilet can turn into a seven- or eight-room house within a matter of months. The additive nature of building is more complex than the similar process in the village, however, because elements of urban apartments are gradually introduced in a selective manner. The study of changes in domestic politics depending on the inclusion or exclusion of corridor spaces (borrowed from urban apartments), for example, will disclose further layers of complexity in spatial relationships. In the gecekondu environments, the languages of the city and the village clash, and other languages emerge. 32

In order to survive, rural immigrants had to discover spatial and architectural tactics of survival and resistance about which the discipline of architecture has so far remained silent. Rural immigrants assimilated, subverted, and mimicked. In doing so, they never denied, in a stubborn traditionalism, the language of the city. I think it is significant that as early as the 1950s gecekondu inhabitants organized to demand modern urban services. 33

The city made use of the immigrants without tolerating their physical presence. Urban professionals recurrently made the rural immigrant their cultural object of analysis whose integration into the city had to be guaranteed. In 1966, a publication by the Social Services Division of the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare suggested that gecekondu communities should not be mistaken for settled, balanced, self-satisfied groups. “A long time is needed for these families to be fully settled and integrated into the urban community. To enable necessary measures, they must be seen as transitory communities settled in transitory areas.” 34 For urban professionals, integration meant speaking the given language of the city. In the early phases of gecekondu building, rural immigrants spoke through rather than in the city they had come to inhabit.

Architectural discourse and practice, which had been obsessed with rural buildings and settings, remained silent about this entire phenomenon. Modern Turkish Architecture, the standard English source on the topic, devotes three sentences to gecekondu settlements in a chapter titled “International Style: Liberalism in Architecture.” Summarizing the economic roots of the rural migration process, it states: “This migration had a profound effect on the urban texture. Big cities such as Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir, where employment opportunities were high, became surrounded by gecekondus. These squatter areas, unsanitary and lacking infrastructure, came to house forty to fifty percent of the urban population.” The next paragraph, on the development of “a lucrative estate market,” is followed by an informative study of major public buildings of the 1950s. 35 I propose that the absence of any architectural elaboration of the gecekondu environments cannot be interpreted as the author’s oversight. An architectural writing tradition based on the study of forms and styles, even when such analysis is backed by sociocultural data, is unable to allocate space for such elaboration.

Rethinking the Question of Rural Architecture

Rural vernacular buildings were represented in the grand narrative of Turkish architecture first in conjunction with the nationalistic imagination of the 1930s and early 1940s and again in the “pluralistic” mood of the 1980s and 1990s. 36 The first move was serious and pedagogical, intended to totalize and homogenize. It looked for architectural models at a time when the Turkish nation was in the making. The second is playful and celebrant and is located in the contemporary cityscape, where every building vies with the others for attention and “anything goes so long as it sells.” Despite these differences, in both cases the complexity of rural Turkey is reduced to a few stereotypical architectural moves.

Since the early years of the republic, rural architecture has been muted through recurrent acts of reproduction by a large number of modernist strategies that avoid addressing issues of representation. I have attempted to highlight some aspects of the complexity of certain architectural and spatial conditions (which are further complicated by issues of ethnicity and gender) that architectural discourse in Turkey has hitherto refused to address. From this perspective, gecekondu environments provide insights into other ways of acting, speaking, and perceiving spatial conditions. Located at the intersection between city and village, between the visible and the sensible, they represent silent interruptions in architectural discourse and ideal urban visions.

My interest in the early phases of gecekondu settlements is not motivated by a desire to romanticize or aestheticize, which would reproduce earlier positions on rural architecture. As I have tried to make clear, I am interested in a long-overdue investigation of other ways of understanding architectural and urban space and in adopting a tone that neither celebrates nor condemns the phenomenon of urban migration, which is wrongly described as “the ruralization of cities.” I am interested in the tactical spaces of the city because they are fluid and multiple and they resist totalization. They speak of architecture in different ways because they are nonpedagogical and nonappropriative. Most importantly, they call for reflections on space and architecture and different ways of writing, designing, and building that are neither pedagogical acts of totalization nor celebrated gestures of pluralism. The gecekondu environments do not offer instant formal clues for the architectural profession to adopt or to appropriate. Their contribution is much subtler and less direct. Gecekondu environments offer alternative ways of thinking about architecture and the city by calling out for the recognition of incommensurable differences.

Endnotes

Note 1: I have explored certain ramifications of this phenomenon in “Between Civilization and Culture: Appropriation of Traditional Dwelling Forms in Early Republican Turkey,” Journal of Architectural Education, November 1993, 66–74. Back.

Note 2: The term “Kemalist,” derived from the name of Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish republic, refers to the cultural politics of the early years of the republic. Under the banner of “Westernization,” political leaders of the period launched a series of reforms ranging from the adoption of the Swiss Civil Code to the transformation of the alphabet from Arabic script to Latin, in order to break all past associations with the Ottoman heritage, the Middle East, and Islam. Back.

Note 3: Quoted in Homi K. Bhabha, “Dissemination: Time, Narrative and the Margins of the Modern Nation,” in Homi K. Bhabha, ed., Nation and Narration, New York: Routledge, 1990, 320. Bhabha emphasizes Benjamin’s insistence on the necessity of retaining fragments as fragments that will never constitute a totality. Back.

Note 4: For an extensive analysis, see Erdal Yavuz, ed., Tarih Içinde Ankara (Ankara in History), Ankara: Middle East Technical University, 1980. Back.

Note 5: I borrow the term “pedagogical” from Homi Bhabha, who makes the insightful argument that “in the production of the nation as narration there is a split between the continuist, accumulative temporality of the pedagogical, and the repetitious, recursive strategy of the performative.” The people, according to him, occupy a double time as both the historical objects of a nationalist pedagogy and the subjects of a process of signification that must erase any prior or originary presence of the nation-people. See Homi Bhabha, “Dissemination,” 297. Back.

Note 6: Herman Jansen, “Ankara Plani Izah Raporu” (Report on the Master Plan of Ankara), Mimarlik, vol. 5, 1948, 22. Back.

Note 7: Jansen, “Ankara Plani Izah Raporu,” 11. Back.

Note 8: Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoglu, Ankara, Istanbul: Iletisim Yayinlari, 1987 [1934], 107. Back.

Note 9: Recounted in Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts into Air, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983, 148–55. Back.

Note 10: Berman, All That Is Solid, 154. Back.

Note 11: Quoted from Gentizon, Mustapha Kemal ou l’Orient en marche, Paris, 1929, in Nilüfer Göle, Modern Mahrem, Istanbul: Metis Yayinlari, 1991, 53. Back.

Note 12: Renata Holod and Ahmet Evin, eds., Modern Turkish Architecture, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1956. Back.

Note 13: For an extensive analysis of this issue, see Sibel Bozdogan and Gülsüm Baydar Nalbantoglu, “Images and Ideas of ‘The Modern House’ in Early Republican Turkey,” unpublished paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society of Architectural Historians, 1992, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Back.

Note 14: The term Siedlung refers to public housing projects built by modernist German architects in the 1920s. They were conceived as a response to industrial workers’ lifestyles and were based on principles of efficiency and productivity. Back.

Note 15: Afet Inan, Devletçilik Ilkesi ve Türkiye Cumhuriyetinin Birinci Sanayi Plani (The Principle of Statism and the First Industrial Plan of the Turkish Republic), Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1933. Back.

Note 16: By “humanistic project” I refer to the project’s relying on the individual’s access to reason as the basis of communal existence and sociopolitical action without questioning the ideological process generating individuality and reason. Back.

Note 17: Nusret Köymen, “Köy Çalismalarinda Tek Müsbet Yol, Köylü Hani” (The Only Positive Development in Rural Works, Peasants’ Inns), Ülkü, vol. 7, no. 40, 1936, 299–302; and Nusret Köymen, “Köycülügün Daha Verimli Olmasi Hakkinda Düsünceler” (Thoughts on Increasing Productivity in Rural Reforms), Ülkü, vol. 13, no. 73, 1939, 27–29. Halkevleri (People’s Houses) were urban institutions founded in 1932 to educate the population along the lines of Kemalist reforms in civic life. Besides their monthly publications, they offered library facilities, organized art courses, supported sports facilities, and conducted research on various aspects of folk culture. Back.

Note 18: Köymen, “Köycülügün,” 27. Back.

Note 19: Zeki Sayar, “Iç Kolonizasyon” (Internal Colonization), Arkitekt, vol. 6, no. 2, 1936, 47. Back.

Note 20: This distinction is based on Roland Barthes’ notion of myth as a second-order semiological system that gets hold of language in order to build its own system. See “Myth Today” in his Mythologies, New York: Hill and Wang, 1984, 109–59 Back.

Note 21: Tansi Senyapili, Gecekondu: Çevre Isçilerin Mekani, (Gecekondu: The Space of Peripheral Labor), Ankara: ODTÜ, 1981, 170; and Tansi Senyapili, Ankara Kentinde Gecekondu Gelisimi: 1923–1960 (The Development of Gecekondus in Ankara: 1923–1960), Ankara: Kent Koop Yayinlari, 1985, 58. Back.

Note 22: Senyapili, Ankara Kentinde Gecekondu Gelisimi, 57–58. Senyapili emphasizes that the minister, Sükrü Saraçoglu, was one of the most sympathetic administrators regarding the illegal settlements, having realized that they did solve the problem of housing for the migrants, although not in an entirely acceptable manner. Back.

Note 23: John Berger (text) and Jean Mohr (photographs), A Seventh Man, New York: Viking, 1975, 43. Back.

Note 24: Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984, xix, 34–39. Back.

Note 25: Adviye Fenik, “Altindag Röportajlari” (Altindag Reports), Zafer Gazetesi, 19 May 1949. Back.

Note 26: Nursun Ertugrul, “Gecekondu Yapim Süreci: Akdere’den bir Örnek” (Gecekondu Building Process: A Case Study in Akdere), Mimarlik, no. 3, 1977, 105. Back.

Note 27: Ibrahim Ögretmen, Ankara’da 58 Gecekondu Hakkinda Monografi (A Monograph on 58 Gecekondus in Ankara), Ankara: AÜSBF Yayinlari, 1957, 25. Back.

Note 28: Latife Tekin, Berci Kristin Çöp Masallari (Berci Kristin: Tales From the Garbage Hills), Istanbul: Metis Yayinlari, 1990, 13. Back.

Note 29: Adviye Fenik, “Altindag Röportajlari,” 15 May 1949. Back.

Note 30: Abdullah Ziya, “Köy Mimarisi” (Village Architecture), Ülkü, vol. 1, no. 5, 1933, 370–74. Back.

Note 31: Adviye Fenik, “Altindag Röportajlari,” 22 May 1949. Back.

Note 32: For a remarkable study of the emergence of a unique type of music from the gecekondu culture, see Meral Özbek, Popüler Kültür ve Orhan Gencebay Arabeski (Popular Culture and Orhan Gencebay’s Arabesque), Istanbul: Iletisim Yayinlari, 1991. Back.

Note 33: Senyapili, Ankara Kentinde Gecekondu Gelisimi, 135. Back.

Note 34: Ibrahim Yasa, Ankara’da Gecekondu Aileleri (Gecekondu Families in Ankara), Ankara: Ministry of Health and Social Welfare Publications, 1966, 46. Back.

Note 35: Mete Tapan, “International Style: Liberalism in Architecture,” in Holod and Evin, eds., Modern Turkish Architecture, 106. Back.

Note 36: I have deliberately left out the 1960s and 1970s, when the interest in “vernacular architecture” was institutionalized, by and large, as an academic discipline dominated by structuralist and hermeneutical approaches. A critique of this phenomenon deserves a detailed analysis slightly outside the scope of this essay. Back.