|

|

|

|

Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey

University of Washington Press

1997

10. Once There Was, Once There Wasn’t: National Monuments and Interpersonal Exchange

The Atatürk Memorial Tomb and the Kocatepe Mosque in Ankara are arguably the two most important monuments of the Turkish republic. The tomb provides for visitations and observances in memory of the founder of the republic; the mosque provides a great place of worship representative of the republican period. Yet their prominent hilltop locations and extensive physical layouts indicate that both are intended to have a much larger significance than these specific ceremonial purposes. The two sites, one Kemalist and the other Islamist, represent the claims of two different “orders” of meanings and values to a dominant position in the public life of the Turkish republic. In this respect, the architecture and ceremonies of each monument separately compose the Turkish past, present, and future.

Moreover, standing at similar elevations and in open view of one another, the tomb and the mosque can appear to be in a relationship of challenge and response. The completion of the Kocatepe Mosque in 1987, some thirty-four years after the completion of the memorial tomb in 1953, added one to one in order to make three, not two: a shrine of Kemalism, a shrine of Islamism, and the polemical relationship between the two.

By their visible juxtaposition in the landscape of central Anatolia, both the one and the other can be perceived as an argument against its counterpart as much as an argument for itself. If public perceptions of the two monuments were drawn in this direction—and there are some signs of such a trend—the parallel siting of the two would lend support to a fabled but misleading perception of Turkish society. 1 As the Kemalist site stands opposed to the Islamist site, so it might be reckoned, nationalism is opposed to religion, modernity is opposed to tradition, and state is opposed to society. The very separateness of the two monuments as distinct architectural and ceremonial entities seems to suggest the possibility of two clearly defined but mutually exclusive alternatives. One would be founded on secular reason, the other on religious faith. One would look to the future, the other to the past. One would rely on top-down strategies of institutional organization, the other on bottom-up strategies of popular mobilization. But have the citizens of the Turkish republic, or, for that matter, the citizens of any modern state, ever faced such a clear set of mutually exclusive choices?

In this essay I compare the “alternative” representations of tomb and mosque in order to clarify the common ground that both monuments address. Each of the two sites attempts to compose two horizons of experience closely associated with the nation-state. On the one hand, individuals live within a mass society of anonymous others through the rationalization of public space and time. On the other hand, individuals live among intimate others linked by circuits of interpersonal exchange. 2 Interconnected but not entirely compatible, the two horizons constitute a stimulus for anxiety, if not paranoia, among the citizens of potential and realized nation-states. Are not our circles of familiarity and intimacy vulnerable to the order of mass and reason? Is not the order of mass and reason vulnerable to their circles of familiarity and intimacy?

The nationalist imagination—so characteristic of the age of mass communication, bureaucratic government, technical knowledge, and rationalized markets—responds directly to these sometimes spoken, sometimes unspoken fears. In the nation-state, the order of mass and reason would become but a projection of homogeneous circles of interpersonal relationships. In accordance with principles of a national order, the relationship of the two horizons would be perfectly composed. The allure of such a projection—its practical realization being another matter altogether—is therefore contingent upon a necessary but not sufficient precondition. The prospects of any nationalist movement would depend upon the preexistence of a certain minimal amount of raw material at the level of social relations: circuits of interpersonal exchange based on a shared language of familiarity and intimacy. Without such a foundation, any imaginative projection of the nation-state would lack credibility, and hence, also, any measure of practicability. That is to say, if the idea of the modern nation is unthinkable apart from a mass of anonymous others, then it is also equally unthinkable apart from a system of face-to-face, person-to-person relationships. The nation is therefore truly imaginable only when the former and the latter come into contact with each other.

To see how the memorial tomb and the Kocatepe Mosque obey this imperative of the contemporary nationalist imagination, we cannot begin straightaway with the monuments themselves. We must first have some understanding of the cultural weight and structural position of circuits of interpersonal exchange in the Turkish republic. In the section that follows, I discuss a shared language of familiarity and intimacy that is widely disseminated in contemporary Turkey.

A Language of Familiarity and Intimacy

In the course of fieldwork in different regions of the Turkish republic, I encountered elaborate vocabularies of personal dignity, intimate exchange, and social relationship. The prominence of such vocabularies, not to mention the large number of conventional greetings, expressions, and proverbs used in everyday conversations, is a direct reflection of the importance of face-to-face, person-to-person association in Turkish society. As an ethnographer, I would have to say that there is not one but many vocabularies of personhood and sociability, such that terms and usages vary from region to region, if not from town to town or even village to village. Yet these differences can also be viewed as local dialects of a common language of familiarity and intimacy.

The common language, I would say, is an artifact of the old regime that has passed over into the new regime. Transformed by and adapted to the environment of the Turkish republic, it is now addressed and claimed by the partisans of both Kemalism and Islamism, even though, strictly speaking, it is neither the one nor the other. Rather, it is an implicit philosophy of social thought and action that serves in its own right as a vehicle of family, kinship, friendship, partnership, and patronage—indeed, of all kinds of unofficial and uncodified associations. 3 It gives rise to a specific form of consciousness that is still associated with face-to-face, person-to-person relationships in salons, coffeehouses, workplaces, and offices. Circuits of interpersonal exchange operate more or less autonomously and independently of public institutions even while influencing their character.

As my notebooks began to fill with glosses on local idioms, I began to press my interlocutors to comment on the principles of social thought and practice. Occasionally I was rewarded with a kind of philosophical discourse in miniature. One of the most intriguing of these responses, which I encountered on more than one occasion, involved what might be called a “theory” of the constitution of personhood in terms of “passion” (nefs) and “intellect” (akil). I have repeatedly found this theory to be a remarkably effective tool for understanding the way in which relationships of self and other are linguistically registered and constructed. In the paragraphs that follow, I summarize this commentary more or less in my own words.

Each individual consists of an essence of “passion,” as designated by the Turkish word nefs. This essence has the quality of a life force that energizes both speech and action. It can be conceived of as a core of motivating emotions and desires, and it is very close to the drives that humans share with animals, such as hunger and sexuality. Indeed, the nefs, as an essence of passion, is what humans have in common with animals. In the case of humans, but not of animals, the nefs can be a driving impulse for behavior that is either noble or base. Neither of these distinctions applies to animal behavior because beasts are no more capable of doing “good” than they are capable of doing “bad.”

To understand this difference, we have to consider a capacity that differentiates humans from animals. This is the faculty of the “intellect,” as designated by the Turkish word akil. By means of the akil, the individual is able to know and accept a system of limits, prohibitions, or restrictions, such that the nefs is properly controlled and channeled. This is accomplished during the course of maturation as one passes from childhood to manhood or womanhood, a process that is synonymous with learning how to present oneself to others. 4 The result is a state of being (hal) whereby the individual is able to participate in social relations with other individuals. It is acknowledged as a condition of legitimate personhood (namuslu bir adam, namuslu bir kadin). The acknowledgment of legitimate personhood can come only from social others. It can never be claimed for oneself by oneself.

By the akil-nefs theory, the individual’s experience of social relations has an erotic quality. We can see this in two ways. First, the system of limits, prohibitions, or restrictions is not abstract or formal in character, but closely identified with intimate social relations. Accordingly, its regulations refer to body, dress, disposition, manner, and speech in a face-to-face, person-to-person setting. The individual is not merely demonstrating a learned skill but is also coming to know who he is and how he feels. Second, the constitution of legitimate personhood is accomplished not by suppressing but rather by shaping an interior of desires and emotions. Face-to-face and person-to-person relationships are a site of proper pleasures. They are occasions on which one contemplates happiness gained or lost. The personal experience of sociability potentially reaches toward a sublime of personhood achieved through association with others.

The language of familiarity and intimacy exhibits a metaphysics of personhood and sociability. A specific form of consciousness is associated with face-to-face, person-to-person relationships. Henceforth I refer to this consciousness as popular intersubjectivity.

Folk Traditions and Imperial Institutions

The portrayal of personhood and sociability in folktales can be shown to conform to the akil-nefs theory. This means that folktales, insofar as they imagine interpersonal exchanges, stand as artifacts of popular intersubjectivity. In what follows, I examine two types of folktales as evidence of “popular” reflections on the official codes of the old regime. We shall see that the law of the sultan (kanun) and the law of Islam (seriat) were perceived as high “orthodox” versions of a language of familiarity and intimacy. At the same time, everyday life was the locus of desires and devices that violated the proper bounds of relationships in the palace and mosque. The folktales point to a low “heterodox” version of a language of familiarity and intimacy in which subversive thoughts and practices implicitly contradict the legitimacy of imperial institutions.

Sultan and Vizier Stories

Folktales about the sultan’s traveling in disguise with his vizier were commonly told in the old regime. 5 Such stories can be considered popular contemplations of imperial authority. Two mighty and august figures are imaginatively transposed from their official location in the imperial palace to the roadways, markets, and coffeehouses of everyday life. By means of the fabulous imagination—“once there was, once there wasn’t (bir varmis, bir yokmus)”—the “high” is conjoined with the “low” to produce a shock that provokes laughter.

The following sultan and vizier story can be considered in these terms. In this instance, the story does not relate the adventures of the sultan and vizier traveling abroad but rather an incident by which ordinary folk are brought into the confines of the palace to stand before the two. I provide only a summary of the plot rather than the full translated text:

The sultan calls on his vizier saying he wishes to be provided amusement. The vizier finds three peasant brothers, each with an itch in a different place on his body—a dripping nose, an infected back, and a mangy scalp. Assembling them before the sultan, he tells them they will be rewarded with a gold piece if they can resist their irritations for an hour. As the hour passes, the three peasants begin to reach the limits of their endurance. Unable to resist their nagging afflictions a moment longer, but unwilling to lose the proffered gold piece, they devise an ingenious response. The first brother points to the Bosphorus, saying, “Look at that fine boat that is passing,” as he runs his sleeve past his sniffly nose. The second immediately responds, “Yes, and they are beating a drum on board,” as he beats his head with his fists. And the third concludes, “And look how fast they are rowing,” as he soothes his back by repeatedly hunching himself to ape the action of the rowers. The sultan laughs and the three brothers receive their reward from the vizier. 6

On the elevated terraces of the palace, a little drama comically illustrates the constitution of personhood at a primary level of human experience. The urge to relieve an itch (nefs) is blocked by a prohibition against scratching. If desire can be controlled by accepting an imperial constraint, a handsome reward will be forthcoming. The three brothers fail the test becaus e they scratch their itches before the allotted time has past. Even so, the sultan is pleased and the vizier gives the reward. Why is this the case?

As the three peasants call out to one another and perform their gesticulations, they refer as a group to the drummers and rowers in the passing boat. At the same time, their words and acts that describe this scene in the world at large signify their separate personal desires. That is, each response is part of a collective communication even as it is also an expression of individual desire. Hence, personal desires are controlled and channeled in accordance with the imposed constraints of interpersonal communication. If the peasants have violated the artificially conceived imperial prohibition, they have demonstrated the common law of sociability and personhood. Therefore they win the reward even though they fail the test.

This is almost right, but not entirely so. The peasants violate the common law of sociability and personhood even as they demonstrate it. Collective representations as expressions of individual desire should be effectively, not artificially, compatible with practical circumstances. From a legalistic point of view, the impracticality of collective representations as expressions of individual desire results in dissension and corruption. But from an everyday point of view, it is common knowledge that norms have to be compromised if sociability is to be sustained. To satisfy the nefs, which appears more as a low animal drive than as a high human ambition, the peasants have subverted the normative akil (intellect) by resorting to a representational akil (cleverness).

The story has staged a confrontation between the high imperial and the low plebeian. The palace formulates and enforces regulations that are intended to control and channel common desires. The peasants, who are the targets of these regulations, know that one can get what one wants only by conforming in form but not in fact. The performance of the three brothers is a reminder that imperial ideals are always defeated by everyday realities. The sultan erupts in laughter and the vizier proffers the gold piece.

The story is an artifact of a language of interpersonal relationship whose propositions are taken for granted. At the same time it suggests that this language is formally articulated in an imperial milieu but subversively manipulated in a plebeian milieu. This aspect of the tale may once have been far more obvious than it is now to citizens of the Turkish republic. The occasion that the vizier devises for the sultan’s amusement bears a close resemblance to one of the most grandiose of all the imperial ceremonies staged within the palace grounds.

Palace Protocol and the Council of Victory

The ruling institution of the old regime took the form of a household organization. The sultan was a head of state who had the status of a family head. The center of his government took the form of family residence. High military and administrative officials were often raised in his residence from an early age and were considered his personal servants. The architecture of the palace grounds and ceremonies that were conducted therein were specifically designed to represent an “intimate and familiar” relationship between the head of state and his military and administrative officials. At the same time, these relationships were also rationalized and formalized in accordance with the requirements of a state organization.

On the occasion of the so-called Council of Victory celebrations in the Topkapi Palace, thousands of the highest military and administrative officials assembled in its middle court to manifest their personhood before the eyes and ears of the sultan, who was, in symbolism at least, personally present. 7 Positioned and dressed in accordance with the rules of palace protocol (kanun), officials stood silent and still, “as though hewn out of marble” for hours at a time. 8 Staged in part for the benefit of foreign dignitaries, these ceremonies were intended to demonstrate the power and glory of the Ottoman dynasty through the behavior of the officials so assembled. A member of the French embassy described one of these occasions held in 1573:

The Ambassador saluted [the highest grandees of the court] with his head and they got up from their seats and bowed to him. And at a given moment all the Janissaries and other soldiers who had been standing upright and without weapons along the wall of that court did the same, in such a way that seeing so many turbans incline together was like observing a vast field of ripe corn moving gently under the light puff of Zephyr.... We looked with great pleasure and even greater admiration at this frightful number of Janissaries and other soldiers standing all along the walls of this court, with hands joined in front in the manner of monks, in such silence that it seemed we were not looking at men but statues. And they remained immobile in that way more than seven hours, without talking or moving. Certainly it is almost impossible to comprehend this discipline and this obedience when one has not seen it.... After leaving this court we mounted our horses where we had dismounted upon arrival.... Standing near the wall beyond the path we saw pass all these thousands of Janissaries and other soldiers who in the court had resembled a palisade of statues, now transformed not into men but famished wild beasts or unchained dogs. 9

The mass of officials, standing silent and still before the symbolic presence of the sultan, were intended to illustrate the constitution of personhood as defined by imperial regulations (kanun). Similarly, the unruly and boisterous behavior of the soldiers upon leaving the palace illustrates, by way of contrast, the human energy controlled and channeled in the constitution of personhood.

The story of the three peasants required to stand before the sultan and the vizier without scratching their itches is an obvious parody of the Council of Victory ceremonies. Originally conceived to draw an invidious comparison between a pretentious imperial ceremony and the subversive practices of everyday life, its point was eventually forgotten in the course of its transmission from the Ottoman past to the republican present. For our purposes, the invidious comparison implies that the palatial and extrapalatial worlds are based on the same language of interpersonal relationship. The difference between the two is also suggested by the simple tale. The palatial world has the properties of a formalized and rationalized construction. The extrapalatial world has the properties of a system of communication and behavior that is honored by its violation.

Nasrettin Hodja Stories

Sultan and vizier stories describe scenes in which the high and mighty come into contact with the low and plebeian. The results often involve ridicule, but the target of the tale is never predictable. Sometimes imperial pomposity and pretension are exposed by an encounter with the realities of everyday life. Sometimes popular hypocrisy and dissimulation are exposed by an encounter with the wisdom of the just ruler. In contrast, Nasrettin Hodja stories more consistently tell of simple people doing ordinary things. 10 By the very logic of this difference, the humor of this kind of story is often at the expense of what is supposed to be right thinking and practice.

Nasrettin Hodja stories tell of an individual who, by his very title (hoca), is understood to be an expert in the sacred Law of Islam, the code of proper personhood and sociability. More than a few Nasrettin Hodja stories are staged in, or very near, the mosque where adult men assemble for Friday prayers. 11 These features of the tales are intended to serve entirely mischievous purposes. The wily hodja teaches us that improper, illogical, and stupefying experiences disrupt and confuse what should be proper, logical, and sensible social behavior.

One of the best known, and one of the shortest, examples of this type of tale follows:

The Hodja’s neighbor wishes to borrow his donkey. The Hodja declines the request saying that he has no donkey to loan out. At that very moment, the neighbor hears the bray of the Hodja’s donkey coming from the stable and rebukes the Hodja for telling a lie, saying, “Do you not hear the sound/voice (ses) of the donkey?” The Hodja replies, “You do not believe my word (söz), but you accept the word (söz) of a donkey?” 12

In this story, the hodja selfishly does not want to lend his donkey and wishes to evade the obligation of neighborly reciprocity. Since he cannot legitimately refuse the request, he denies that he even has a donkey. When caught in this deception, the hodja accuses his neighbor of believing the donkey’s sound (ses) in order to fault the word (söz) of the hodja. In effect, the neighbor improperly attends to the donkey, a brute beast wholly lacking in moral qualities. The joke of the story involves the hodja’s attempt to invoke the norms of personhood and sociability at the very moment he is caught violating them.

As in the sultan and vizier story, the akil/nefs theory is an implicit, not an explicit, feature of the Nasrettin Hodja story because its propositions are taken for granted. The contrast between the donkey’s bray and the hodja’s speech is a contrast between the utterances of living creatures with and without akil. The hodja’s words should reflect his recognition of the rules of personhood and sociability, a recognition whereby instinctive selfishness would be replaced with affectionate generosity. Once again, we see how the normative akil (intellect), by which one registers social constraints, becomes instead a representational akil (cleverness), by which one conceals motives, evades the law, and misleads others. Thus, the behavior of Nasrettin Hodja reveals the nefs as an anarchical and disorderly energy that subverts the proper form of interpersonal communication and relationship.

The Sacred Law and the Friday Prayers

Nasrettin Hodja, the hero of stories in which proper communication and relationship are subverted, is simultaneously a pillar of respectability, an expert in the sacred law of Islam, and a leader of Friday prayers in the mosque. He is betwixt and between the everyday utterances (parole) and the orthodox grammar (langue) of a language of interpersonal relationship. As a master of the former, he is a punster and trickster. As the master of the latter, he knows the law, delivers the Friday sermon, and leads the prayers. So the language of interpersonal relationship, which is “at risk” and “in play” in the Nasrettin Hodja stories, is assumed within the narrative tradition itself to have a connection with the beliefs and rites of Islam.

The connection is clearly spelled out in a contemporary “science of being” manual (ilmihal) published to provide instructions for the proper observance of religious obligations. 13 In the section on “Worship,” for example, the author explains the obligation to perform the five daily prayers in terms that recall the language of interpersonal relationship we have been considering. He begins with the sentence, “Worship is a way of honoring and revering God.” 14 Its terms “honoring and revering” (saygi ve ta’zim göstermek) could also be applied to the kind of behavior that is enjoined before the father, elder, patron, lord, or sultan.

In his next sentence, the author describes the relationship of worshiper and divinity as though it were a relationship of client and patron. The believer has the duties of a servant (kulluk görevi) who has received generous gifts from his august and mighty (yüce) creator. The believer is obliged to return his thanks to God just as he would be obliged to someone “who offers his place on a bus or a glass of water.” The author then characterizes worship as a form of spiritual nourishment (ruhun gidasi) that is equivalent to bodily nourishment (yemek ve içmek). The theme of the quenching of hunger and thirst leads to a description of prayer as the means for controlling and channeling the nefs:

In worship, we always fight with the bad feelings of the nefs and we draw them out of the spirit. We cleanse bad thoughts from our spirit. In this way, we become a completely clean human being both inwardly and outwardly. In the truest sense, someone who performs prayer has become the master of the desires of the nefs. He has become bridled (gem vurmus). He does everything in its proper place and by its proper measure. The greatest battle is the war with the nefs. The greatest form of bravery is to become the master of the nefs. 15

The author concludes by portraying the five prayers as the means for constituting personhood before the presence of divinity. The result is a sublime of personhood achieved through association with God, rather than through association with others:

With the five prayers one is able to be nourished by God’s great riches, to be purified by contact with his mercy, to present oneself and to humble oneself before the God of man and to come into a relationship with His meaning, and to establish in the body the material and spiritual order in the cosmos. 16

The same metaphysics of personhood and sociability that is part of everyday life reappears on the level of state and religion. From the perspective of the language of interpersonal relationship, the Friday prayers and the Council of Victory are paradigmatically equivalent. Believers perform their ablutions and then assemble with their neighbors in the mosque. Standing in ranked formation before the niche (mihrap) oriented toward Mecca (kible), they enact in unison words and deeds that are addressed to God and scripted by the sacred law (seriat). Substitute sultan for God, kanun for seriat, officials for believers, palace for mosque, and sovereign power for religious truth and the result is the Council of Victory. This means that the imperial palace and the imperial mosque each stake a separate claim on popular intersubjectivity. Rationalized and formalized as kanun, it is the basis of a ruling institution. Rationalized and formalized as seriat, it is the basis of divine creation.

With this understanding of the cultural weight and structural position of a language of interpersonal relationship, we can now examine the sites of the memorial tomb and Kocatepe Mosque. As in the old regime, representations of state and religion in the new regime stake a claim on popular intersubjectivity. The entirely new environment of a mass society of anonymous others drives these representations in new directions.

The Memorial Tomb

In the fall of 1922, the Grand National Assembly, at the urging of Mustafa Kemal, resolved that a government consisting of the “sovereignty of an individual had ceased to exist... and passed forever into history,” thereby bringing to an end the Ottoman sultanate. 17 In the spring of 1924, having already proclaimed the republic with its capital at Ankara, the Grand National Assembly, again persuaded by Mustafa Kemal, abolished the caliphate and the sacred Law of Islam. 18 These events recall how the new nation-state was contingent on the suppression of two key institutions, Ottomanism and Islamism—one the sovereignty of an individual, and the other a system of a divinely revealed law. The citizens of the republic would represent their existence in terms of a new past, present, and future. A new way of being would displace the old. Ottomanism would be inoperable because it would have no register in thought or feeling. Islam would remain a matter of private practice and sentiment, rigorously excluded from public life.

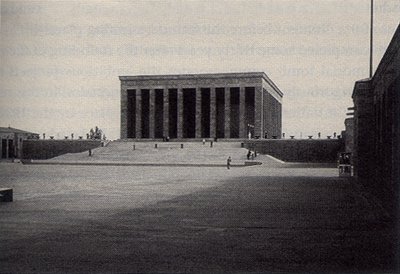

Soon after Atatürk’s death on November, 10, 1938, the decision was taken to erect a monument in his memory (figs. 10.1, 10.2). From the outset, the Atatürk Memorial Tomb (Anitkabir) was conceived of as a great ceremonial center for the Turkish nation. In this respect, it was part of the effort of Turkish nationalists to define, and thereby control, the symbolism of public life. 19 It would be sited on a prominent hill overlooking Ankara and surveying the plains of central Anatolia. Its spaces and buildings would be of exceptional magnificence and grandeur, making it one of the most ambitious architectural projects of the republican period. Its material composition, consisting of marble and stone quarried in dispersed sections of the new national domain, would reflect the territorial integrity of the nation. After a design competition was held in 1941–42, a jury of international membership selected the project of a Turkish team, Onat and Arda, for the realization of the monument. 20 Ground was broken on September 9, 1944, and construction proceeded for almost a decade, during which time the original design continued to be reworked. 21

|

| 10.1. Anitkabir, the Atatürk Memorial Tomb, from the central square looking toward the Hall of Honor. (Photograph by the author.) |

|

| 10.2. Anitkabir, from the Hall of Honor looking toward the central square. (Photograph by the author.) |

On November 10, 1953, the fifteenth anniversary of Atatürk’s death, his body was transferred by official state procession from the Ethnographic Museum and laid to rest in a crypt in the Hall of Honor. 22 Since that time, the memorial tomb has served as a site for rites commemorating the founder of the Turkish republic. Official ceremonies are conducted there on the anniversary of Atatürk’s death, during visits to Turkey by foreign heads of state, and on other official occasions of state. Members of private and public associations—including schoolteachers, schoolchildren, military officers, business executives, municipal officials, and club members —may assemble at the tomb to pay their respects to Atatürk. Groups of ordinary citizens also visit the site to browse through its museum displays, admire the views of the countryside from its walkways and courts, and pause for a moment before the founder’s resting place. 23

Though completed some thirty years after the founding of the republic, the memorial tomb commemorates the ambitious projects of nationhood so vigorously pursued during its first decades. In this respect, various theses of nationalist ideology, firmly in place by the 1930s, are referenced by the features of its buildings’ decors and facades. Thesis: the arts of civilization will flourish in the new Turkish republic. Reference: bas-reliefs and sculptures represent the people of the new nation. Thesis: the Turks have been a nation of Anatolia since ancient times, their earliest representatives being Sumerians and Hittites. References: the pathway from the outer wall to the central court is lined with Hittite lions, and the Hall of Honor was intended to resemble a Sumerian ziggurat. 24 Thesis: the Turkish republic is a representative of the Turkish folk of Anatolia. Reference: walls and ceilings feature abstracted motifs of Turkish flatweaves in paint and mosaic.

Though such references are encountered, the memorial tomb was designed as a place for solemn visitations and observances rather than for the display of nationalist ideology. During informal and formal visits, citizens of the Turkish republic would recall its founder and pay him their respects. In this regard, the tomb is a site for interpersonal exchange between citizen and founder. Symbolically at least, the citizen can be heard and seen by the founer, just as the founder can be heard and seen by the citizen.

Informal Occasions: The Personhood of Atatürk

On informal occasions, visitors view the sculptures, inscriptions, and artifacts of the memorial tomb as they stroll about its walkways, courts, and museums. Hard-edged bas-reliefs depict Atatürk leading the Turkish people during the War of Independence. Excerpts from his speeches, inscribed in the new romanized script, appear in the form of gigantic tableaux. At one corner of the site, visitors see the cannon carriage that was used to transport Atatürk’s body to the tomb. At another corner, they see his official and ceremonial cars, in which he toured the nation. At another location, designated the Atatürk Museum, they can view his personal possessions: shoes, suits and hats, shirts, collars, handkerchiefs, cuff links, walking sticks, a stickpin, ties, toiletry articles, his hand mirror, eyeglasses, cigarette holders, military medals, a uniform, a pistol, a desk set, samples of his handwriting, a library, and twinned photographs of himself and his mother. They also find a display of personal gifts from the heads of the newly organized institutions of the republic, such as the Industrial Bank, the Post, Telephone, and Telegraph, and the Grand National Assembly.

Going on to the rooms designated the Art Gallery, they see money and stamps with representations of the face and figure of Atatürk. Eventually, they enter the Hall of Honor itself and approach the symbolic tomb of Atatürk, located above the actual tomb. Here they contemplate a national leader and founder of the republic against the backdrop of the Anatolian countryside.

The informal visitor to the memorial tomb is able to know the personhood of Atatürk through the lens of national destiny, most coherently by his leadership during the War of Independence, but also, more vividly and intimately, by personal possessions from the period in which he was president of the Republic of Turkey. In this respect, the memorial tomb does not tell the story of national history, refer to attributes of a national tradition, teach the principles of national citizenship, or explain the national constitution. At the most important site of the republic, the nation is not conceived of through its history, ideology, laws, or constitution. Rather, the argument of a language of familiarity and intimacy has been reformulated in the terms of citizen and nation.

Formal Occasions: Assemblies in the Central Court

The coordination of architecture and ceremony during formal visits to the Atatürk Memorial Tomb demonstrates this reformulation openly and explicitly. On state occasions, smaller or larger assemblies pay their respects to the founder of the Turkish republic. Individuals stand in ranked formation in the central court, before the Hall of Honor. They are in the personal presence of the national leader and founder. He observes and listens as they stand silent and still. 25

Before their eyes, they can see a plinth on the steps leading to the Hall of Honor. On it they can read a message from the founder, inscribed in romanized letters: “Without condition or restriction, sovereignty belongs to the nation” (Hakimiyet kayitsiz sartsiz milletindir). The message announces not the democratic principle of popular representation but the condition of external constraints that impinges on each individual, not the least of whom would be the founder himself. Personhood is constituted within the space and time of nationhood.

Looking to the left, participants can make out the “Address to Youth” behind the frontal colonnade of the Hall of Honor. This address calls for defense of the homeland in the worst of times. Its message concludes with a call for individual sacrifice: “O Turkish children of the future!... save the republic! The power exists in the noble blood that runs in your veins!” Looking to the right, viewers can make out the address to the Turkish nation on the occasion of the “Speech of the Tenth Year,” again behind the frontal colonnade of the Hall of Honor. This message concludes with a sublime of personhood achieved through national association: “How fortunate is he who can say, ‘I am a Turk.’”

The citizen stands before the Hall of Honor in the presence of the leader and founder in order to pay his respects. The three written communications announce the framework within which this interpersonal exchange takes place. Citizen and founder interact within a framework of constraints imposed by nationhood. In exchange for individual sacrifice there is the promise of the sublime.

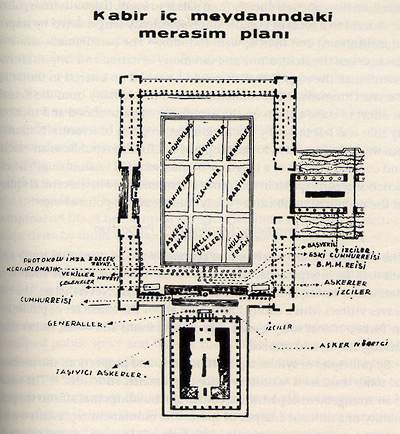

At the site of the memorial tomb, architecture and ceremony are coordinated in accordance with a paradigm that recalls the Council of Victory at the imperial palace. Tomb substitutes for palace, the symbolic presence of national founder for that of dynastic ruler, a central court (iç meydan) for a middle court (orta yer), high officials of the republic (cümhürreisi, b.m.m reisi, generaller) for high officials of the palace, representatives of a national polity (meclis üyeleri, mülki erkân, askeri erkân, vilayetler, cemiyetler, dernekler, ve partiler) for household staff (kullar), diplomatic officials in residence (kordiplomatik) for visiting foreign embassies, and modern dress (sapka, kravat, and kostüm) for imperial sumptuary (fig. 10.3). 26 A narrow loyalty between a dynastic ruler and his household staff has been converted into a broad loyalty between a national founder and a national elite representing a national citizenry.

|

| 10.3. Anitkabir, plan for ceremonies in the central square. (Reproduced from the memorial tomb brochure, Devrim Gençligi Ilavesi, ca. 1953.) |

In the Atatürk Memorial Tomb, we have a ceremonial center of the nation-state, first chosen as a design in 1942 and finally completed in 1953, that parallels a ceremonial center of the old regime, already defunct in 1853. 27 But insofar as this is the case, the imperial legacy in Turkish nationalism does not pass directly from palace to tomb. It detours from palace downward to a form of popular intersubjectivity (engendered by imperial institutions) and then upward to tomb. 28 The paradigmatic similarities between the architecture and ceremony of nation and empire are not intentional; the early Kemalists would have had no interest in imitating the late Ottomans. 29 The similarities result incidentally from the Kemalist effort to stake a claim on the experience of personhood and sociability that was left intact by the nationalist program of reforms. Nationalism was to be presented to the people of the Turkish republic as an official and codified version of a language of interpersonal relationship. The experience of participants in the formal ceremonies held in the central square of the memorial tomb can be easily read from this point of view.

Symmetry, Rectilinearity, Proportion

The scripting of architecture and ceremony at the memorial tomb emphasizes an interpersonal exchange, rather than the various strands of nationalist history, ideology, or constitutionalism. Nevertheless, the site leaves visitors with a strong impression about the character of public life in Turkey. It does so by means of geometric forms and voids, rather than through myth and symbol.

By principles of symmetry, rectilinearity, and proportion, the memorial tomb constructs “a unitary space of geometric structure.” 30 The result is an arrangement of pathways, courts, and buildings that affirms the possibility of a rational analysis of space. The monument represents a consistent and pervasive intention. The form of the parts always points to the presence of the whole. The overall lack of emphasis on decor and facade at the monument does not allow visitors to miss this point. The relative absence of historical references and aesthetic intentions, given the elaborate ideologies of the nationalist movement, forces visitors to recognize the abstract logic of its geometric rationality. In the Turkish republic, the combined projects of modernity and nationhood involved the planning and construction of a public space and time for a mass society of anonymous others. The principles of reason and science set the new modernist and nationalist regime apart from the old personalist and imperialist regime.

The striking feature of the design principles at the memorial tomb is the omnipresence of geometrical frames. Walkways and courts, quotations and bas-reliefs, colonnades and arches, borders and pavements all take the form of rectilinear frames. One is always obliged to walk, to read, and to look through frames set within frames. When the eye shifts toward the capital city and the Anatolia countryside (and they are constantly visible as one moves about the site), they are always seen through frames set within frames. Frames within frames impose themselves on the movements and perceptions of the ordinary citizen during his or her informal visits to the site. Frames within frames organize the officials who stand in ranked assemblies during the formal occasions of state. In this fashion, architecture and ceremony at the tomb define a space that obeys a consistent and coherent rationale, signifying a consciousness of citizenship defined by limits and boundaries.

If this is a modernist-nationalist public space and time, however, it is of a special kind. The memorial tomb does not invite the individual to comprehend his or her status as citizen of a nation so much as it defines subjectivity by limits and boundaries. This is not so much a space of Enlightenment reason and history as a space of akil, a space experienced as a constrained interpersonal relationship. The memorial tomb is not a Hobbesian, Kantian, Hegelian, or Durkheimian site. Its philosophical underpinnings are elsewhere.

Designed in accordance with the new techno-scientific norms of rationalized public space and time in the Turkish republic, the memorial tomb takes on a very different meaning in its address of popular intersubjectivity. Brochures about the tomb, featuring a bust of Atatürk on their covers, represent the site itself as empty of a human presence. 31 Schematics of the site that illustrate the layout of its buildings and museums feature recticulated grids. 32 Pictures of the site usually show its walkways and courts as voids. When one visits the memorial tomb, one should not hold hands. One should not sit. One should not laugh. A unitary space of geometric structure oscillates between national identity and individual sacrifice and death. As a pure representation of the limits and boundaries of consciousness, there is nothing left for interior desire save its extinction in the name of the nation.

The Kocatepe Mosque

The Atatürk Memorial Tomb is arguably the most important site of state ceremony in the Turkish republic. Designed and built at a time when modernist influences on the nationalist movement were on the rise, it stands as a monument to the project of replacing an old order with a new order. And yet we have found that the Kemalist encoding of the nationalist imagination cannot be understood apart from its attempt to claim and exhaust the sphere of popular intersubjectivity. Turning now to the Kocatepe Mosque, we find that the tables are turned. This “great place of worship” (ulu mabet), newly completed in 1987, was designed and built during a period of Islamic resurgence and was intended to stand as a monument to the place of religion in Turkish society. If, however, we consider the coordination of architecture and ceremony at the mosque in terms of both the intentions of its architects and the perceptions of its caretakers, we discover that it is locked in an argument with the memorial tomb.

The idea of building a mosque in the new capital of the Turkish republic may have been proposed as early as 1934. 33 In any case, such a project was being discussed shortly after the decision was taken to build the memorial tomb. With the encouragement of officials in the Ministry of Religious Affairs, a building committee was formed in 1944, and a design competition was held in 1947. None of the entries was awarded first place, but the project submitted by Alnar and Ülgen, which proposed a structure in the simple and modest style of the earliest Ottoman mosques, received considerable support. 34 The initiative then faltered until 1956, when a personal intervention by the prime minister revived it.

Now the decision was taken to build a great place of worship in an architectural style that would “reflect the republican period” (Cumhuriyet dönemini temsil edecek). 35 The site of Kocatepe was chosen so that the structure would be within the urban precincts on a hill “dominating Ankara” (Ankara’ya hakim). 36 After another design competition in 1957, the jury awarded a first prize to the project submitted by two Turkish architects, Dalokay and Tekelioglu, but it was not recommended for construction until certain revisions had been undertaken. The winning project proposed a mosque in the form of a sectioned “rind” or “skin” with minarets stationed at each of its four corners. This modernistic structure was to be set among, or coordinated with, other buildings, a practice that otherwise recalled the classical Ottoman “mosque complex” (külliye). These buildings were to house a library, a conference room, a museum, a two-hundred-vehicle autopark, a tourist market, a kitchen, a polyclinic, the offices of the Ministry of Religious Affairs, and the campus of an Advanced Islam Institute.

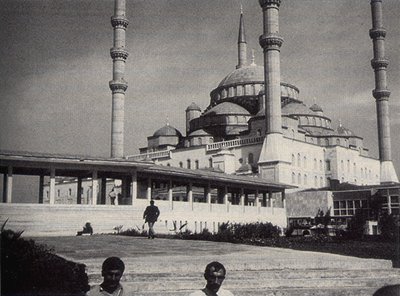

Although some of the buildings, such as the offices of the Ministry of Religious Affairs, were eventually completed, the design for the mosque remained controversial. Objections to the structural soundness of the “rind” or “skin” design, which some defenders of the mosque considered entirely specious, eventually prevailed. Yet a third design competition was opened in 1967. The winning project, submitted by Tayla and Uluengin, proposed a gigantic structure that closely resembled an Ottoman mosque of the classical period. Construction began on October 30, 1967, and continued off and on for twenty years, owing to periodic shortages of funds. Eventually, in 1981, the Religious Endowments of Turkey took over the financing, and construction proceeded apace. First proposed in the 1930s, debated as a project for thirty years, and fitfully under construction for twenty, Kocatepe Mosque was officially opened on August 28, 1987, as a “national place of worship” (fig. 10.4).

|

| 10.4. Kocatepe Mosque, from the stairways leading to the plaza. (Photograph by the author.) |

The reference point for the design of the new mosque had shifted back and forth in historical time. In 1947, the mosque proposed for the capital had been one of modest dimensions that drew upon the single-unit mosque of the early, pre-imperial Ottoman period. In 1957, the concept of a national place of worship was explicitly formulated, the projected size of the mosque expanded accordingly, and a postimperial, modernist design was favored. By 1967, the national place of worship was contemplated in conjunction with a capital city whose population now exceeded one million souls, and the projected size of the mosque complex surpassed the scope of the 1947 and 1957 designs by far. 37 The new mosque was to be modeled on the classical Ottoman mosque, the glorious architectural achievement of the high imperial period. Its prototype is said to be the Sultanahmet Mosque, a late Ottoman mosque of the early seventeenth century, save that the scale of the new national mosque is intended to exceed that of the imperial structure it emulates. 38

My Visit to the Kocatepe Mosque

In the fall of 1987, I was graciously welcomed at the Kocatepe Mosque by two officials of the Religious Endowment of Turkey. They were enthusiastic about the new mosque, which had been inaugurated little more than a month earlier, an occasion that was attended by many thousands of citizens. During a tour of the site, one of my hosts explained the history of the mosque’s construction, its purpose and symbolism, its relationship with the surrounding buildings and landscape, and the significance of what could be seen from its various prospects.

Taking me first to the central mosque building, my host claimed that the interior (harem) was considerably larger than that of the classical Ottoman mosque. Whether this is true or not, my host’s emphasis on its immensity is impressionistically exact. The space beneath the dome of the mosque seems very, very large in comparison with its classical predecessors. The effect had been achieved, my host explained, by the use of advanced techniques of construction, that is to say, reinforced concrete. Contemporary architects and builders could mimic the form of the classical mosque but free themselves from the limits of a dome system fashioned from stone and mortar. The four inner columns that support the dome in the classical mosque are necessarily huge for structural reasons, but the four inner columns of the Kocatepe Mosque could be reduced in width and yet raise the central dome (ana kubbe) to a greater height. Accordingly, the dimensions of the furnishings and accouterments of the mosque also had to be expanded. The niche indicating the direction of prayer (mihrap) and the staired pulpit (minber) are towering. The galleries (mahfel) are doubled to fill the space between the floor and the elevated dome.

Kocatepe Mosque does not just imitate, it also exaggerates its imperial exemplar—but by what logic? As we shall see, the mosque would symbolize the public sphere of the nation, but in a peculiar way. As one might have guessed, the use of advanced construction techniques is supposed to symbolize the modernity of Islam during the republican period. To some degree, this must have been the architects’ intention, and it was certainly on the minds of my hosts. They mentioned various features of the mosque building which demonstrated that Islam during the republican period was modernist (çagdas) in the sense of being technically advanced and sophisticated. Each of the four minarets is equipped with an automatic elevator. A centralized heating system warms the floor. A conference room features an intercom system connecting each seat with the podium. Lighting is provided by electrified chandeliers taking the form of large illuminated globes.

But my hosts did not consistently argue that the mosque demonstrated the technical prowess of its designers and builders. On the contrary, they justified the abandonment of the “rind” design of 1957 by claiming that it exceeded the capacities of Turkish construction firms. 39 Rather, the logic of the Kocatepe Mosque, which differentiates it from the Sultanahmet Mosque, has to do with its referencing of the nationalist imagination, the experience of a mass society of anonymous others. This is what lay behind my guide’s repeated emphasis on numerical quantities and measurements. The Kocatepe Mosque projects an image of a vast throng of believers coming from all over the nation and assembling as a great indivisible unity. Viewing a series of spatial voids and hearing a litany of magnitudes conjured up the presence of an immense crowd of interacting believers.

Leaving the interior of the mosque building, my host took me to the adjoining auditorium, where conferences could be held. The seating capacity (six hundred persons) was duly noted, and the intended purpose of the intercom system was demonstrated. We then explored three further floors under the mosque itself, consisting of 15,000 square meters of space. Still under construction at the time, these floors had been provisionally set aside for a vast supermarket with luxury goods. But some were arguing that the space would be better used for cultural and educational purposes, such as book fairs or museum displays. 40 Leaving the buildings, we walked about the monumental forecourt, which is bordered by domes the dimensions of which are not very different from those of the largest Ottoman mosques.

Then, as we exited the forecourt, my guide’s narrative became more animated and acquired a new intensity. A vast, paved space with no exact precedent in the older mosque complexes surrounds the new mosque building. My host claimed that 24,000 people could assemble to perform the prayers within the mosque and 100,000 could be accommodated in the combined space of the interior, forecourt, and surrounding plaza. As the tour continued, he pointed out the various features of the mosque that were designed to accommodate, but also to symbolize, the assemblage of large masses. There are three large, marble-paneled rooms for performing ablutions (gasilhane), two for men, one for women. There are eight marble slabs (musalla taslari), set out in a single line, for laying out the corpse on the occasion of funeral ceremonies. 41

My host led me through covered passageways lined chock-a-block with hundreds, perhaps thousands, of little compartments for the depositing of shoes. He took me to view the wide stairways rising to the site where he spoke of thousands and thousands of believers coming and going. He then explained how a main thoroughfare of Ankara (between Küçükesat and Mithatpasa) passed directly under the mosque building. This meant that the Kocatepe Mosque was connected with the mass transportation system of the capital city. Descending into the two-story, underground garage, he described how it would enable the efficient massing of believers. 42 Large numbers of citizens might arrive by bus or automobile (vehicle capacity 1,200), move quickly by foot to the interior of the mosque, perform their ablutions and prayers, and return to their vehicles to make their way back to their homes or workplaces.

The classical Ottoman mosque took the form of an intricate structural system of domes, half domes, and small domes. This peculiar structure, achieved only after decades of variation and experimentation, was determined by the objective of raising as large a dome as possible over as large an open space as possible. 43 The result was a magnificent interior where thousands of believers might assemble on the occasion of the Friday prayers. Such a mosque monumentalized Ottoman support for Islamic society, but it had nothing to do with masses and anonymity. 44 In the late twentieth century, during the age of the nation-state, a replica of the imperial mosque has taken on a new meaning altogether: it is a place of worship in a mass society of anonymous others. As my host took me from one spatial void to another, he always saw them filled with people coming from all parts of the capital and all parts of the nation. 45 The brochure he provided, here translated and quoted verbatim without omissions, makes the same point:

“The mosque”... as its name implies, gathers together... At the delayed opening of Kocatepe during Ramazan of 1986, this meaning was actually experienced... Kocatepe was filled to overflowing with the faithful who hurried to come from surrounding provinces (il), districts (ilçe), and regions.... [T]his streaming to Kocatepe, the greatest place of worship of the Republican period... was explaining the yearning of the Turkish nation for growing and uniting. 46

Here again is a sublime of personhood achieved through national association, but it has been strangely transformed into a scene of an anonymous nation-state solidarity (complete with references to bureaucratic districts) that nonetheless satisfies a personally experienced yearning (hasret) for coming together.

As we have seen, “science of being” manuals (ilmihal) commonly explain canonical beliefs and practices as the means for controlling the passions of the self (nefs). According to such a logic, the Friday assembly is that occasion when individuals come together as a community, stand before the niches in the mosque, orient themselves toward Mecca, and manifest their personhood before the presence of divinity. I have taken pains to repeat these matters because neither my guide nor the brochure contemplated the mosque according to such an Islamic canon, but associated it with an image of a desire for assembly among thousands and thousands of believers coming from here and there all over the Turkish nation-state.

Guide and brochure reveal that the Kocatepe Islamists are contemplating the new mosque as a means of composing the two horizons of experience: circuits of interpersonal exchange and a mass society of anonymous others. Having reached this conclusion, I can see in my mind’s eye the crisscrossing and intersecting lines that inscribe the broad plaza of the mosque, the curvilinear arabesques of the painted walls and ceilings, and the geometrical interlacing of windows, doors, and their framing. But at the same moment, I also recall the main thoroughfare by which buses and cars reach its underground parking garage, the conference room where each seat is fitted with devices for electronic communication, and the vast space beneath the forecourt that was to be a supermarket, department store, or book fair. Architectural motifs of the classical mosque and techno-scientific artifacts of mass society are jarringly fused together out of a yearning for association.

The Kocatepe Mosque offers the promise of a faceless national massing that would nonetheless fulfill a personal longing for interpersonal association. Kocatepe Mosque may look like a classical Ottoman mosque of the high imperial period, but it is intended to stake an Islamic claim on popular intersubjectivity in a mass society of anonymous others. The Kocatepe Mosque, like the Atatürk Memorial Tomb, also grapples with two horizons of experience, but in a different way.

Clearing a Space in the City

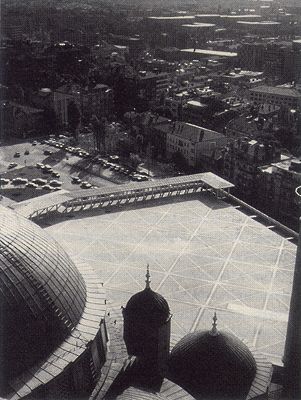

The mosque, like the tomb, moreover, is designed to impose itself on the city. Before beginning my tour, my two hosts explained why Kocatepe had been chosen as the site for constructing a “national place of worship.” First, it was a hill that was clearly visible from many points in the city of Ankara. And second, the existing structures on this hill could be demolished to provide a sweeping view of the city. 47 The mosque complex was to appear as a distinct silhouette visible from many other parts of the city, just as most of the city would be visible from the grounds of the mosque complex. The site was chosen, therefore, to establish a relationship between the mosque and the capital. The space and time of the former would be coordinated with the space and time of the latter. This objective had a direct influence on the design of the minarets and the plaza. The four triple-tiered minarets are higher than any others in Turkey. 48 The plaza achieves more than providing a large space for the overflow of believers who might assemble at the mosque. Described as a “plateau” (plato) in the brochure, it is constructed as an elevated viewing platform that provides sweeping vistas of the surrounding city (fig. 10.5).

|

| 10.5. Kocatepe Mosque, from the minaret looking down to the plaza. (Photograph by the author.) |

During our walk together outside the mosque building, my host took me out to the plaza’s edge. Making a gesture, he said, “Look there in the distance, what do you see?” Following the motion of his hand, I saw the outline of the Hall of Honor of the memorial tomb in the distance, seemingly more or less at the same level as the plateau on which we stood. The new national place of worship, no less than the memorial tomb, occupied a prominent place in the landscape (the minarets of the mosque are clearly visible from the central square of the tomb). This had been, he told me, the explicit objective of the designers and builders of the Kocatepe Mosque. As its architects planned their mosque, as its caretakers provide tours of the mosque, and as ordinary citizens visit the mosque, they have had the principal monument of the Turkish republic in the back of their minds.

Later, my host insisted that we take an elevator and ascend to the top of a minaret. From atop it, he described once again how the mosque dominated the capital as we enjoyed the splendid view of the city of Ankara. And once again, he pointed out the memorial tomb, which was not in the center but on the edge of the city and which was now not merely on a level with but actually well below our station. The Kocatepe Mosque, no less than the memorial tomb, had been conceived within the framework of the nationalist imagination. Indeed, the tomb is the precondition for the mosque, which does not stand singly and alone in the imagination of its designers or caretakers but stands as a response to the challenge of its predecessor in the distance. The Kocatepe Mosque is intended to compete with the Atatürk Memorial Tomb for the definition of the space and time of capital and nation.

This leaves us with the following questions: In what way do the two monuments compete with one another? How do they differently define the experience of space and time in the city and the nation? To find answers to these questions, we have to understand how the two monuments draw different relationships between the two horizons of experience: circuits of interpersonal exchanges and a mass society of anonymous others.

Here and There, Presence and Absence

After the tour, I again sat with my two hosts in their offices. Without my raising the issue, they explained how the Kocatepe Mosque represented a side of the Turkish nation (millet) that had been heretofore unrepresented at the memorial tomb. For them, what was “present” at the mosque had as its precondition what was “absent” from the tomb. What was this thing? One could easily answer by stating that the Kocatepe Mosque represented the place of Islam in the life of the nation. But what does such an answer tell us, after all? What would this proper name, “Islam,” have meant for my two hosts? To what aspect of their individual experience would such a term, “Islam,” refer? My hosts did not speak of so vague a generality as “the place of Islam in the life of the nation.” They explained what was present at the mosque and absent at the tomb by pointing to our experience together in the privacy of their offices.

During our meeting, we had exchanged greetings, we had sat together, we had sipped tea together, and we had conversed together. As is usually the case on these occasions, I had been asked my name, my profession, and my place of residence. They inquired about my father and mother and about my own family. Now, as we contemplated the difference between the mosque and the tomb, one of my hosts posed the question, “Don’t you notice something different about your visit here and your visits to other government offices?” I did not understand what he meant. “Here,” he said, “our relationships are softer and our conversation is more pleasant.” His colleague nodded in agreement. I understood then that they were pointing to the experience of interpersonal relationships, and in doing so, claiming this experience to be exclusively associated with the relationships of believers.

This is the same sentiment that had been articulated in the mosque brochure, in which a mass desire for a sublime of personhood achieved through national association is described as “the yearning of the Turkish nation for growing and uniting.” For my two hosts, Kocatepe Mosque draws a new kind of relationship between popular intersubjectivity and a mass society of anonymous others. The experience of a mass society of anonymous others opens up a void in the psyche of Turkish citizens. Moreover, the memorial tomb, where the relationship between personhood and nationhood demands sacrifice and death, symbolizes that very void. In response, a gigantic Islamic monument is a countersymbol that represents the possibility of filling this void. Kocatepe Mosque figures a national solidarity as an Islamic experience of personhood through sociability.

Thinking about this conversation sometime after my visit, I recalled an incongruous element of the gigantesque mosque complex. At the center of the complex, tucked away among its colossal buildings, an open-air grape bower is maintained for the pleasure of its higher officials. Sometime around 1970, I was served tea there by acquaintances in the Ministry of Religious Affairs, which had recently been completed as the first phase of the Kocatepe complex. Throughout all the razing and demolition that took place during the twenty-year construction of the site, it was somehow preserved intact. The survival of the grape bower, an exemplar of hundreds of thousands in the towns and villages of Anatolia, is perhaps not an accident. It stands as a naked representation of intimate and familiar association, which the Kocatepe Mosque, now looming before it, monumentalizes as a dimension of nationalist space and time.

Conclusion

When the Atatürk Memorial Tomb was completed was 1953, the single-party system had given way to the multiparty system. The tutorial democracy of the Turkish republic had become a practicing democracy. Nonetheless, the architecture and ceremony of the new site did not represent concepts of citizenship, assembly, and constitution so much as they refigured an older grammar and vocabulary. For the Kemalists, the constitution of personhood had to be removed from circuits of interpersonal exchange and transposed to a mass society of anonymous others. This was accomplished by staking an absolute claim on a language of familiarity and intimacy, such that nothing was left over for the interpersonal loyalties of everyday experience. The colonnades, buildings, pavements, and facades of the memorial tomb feature rectilinear frameworks signifying the extinction of individual desire. The exchange between citizen and founder represents personhood though sacrifice and death in the name of nationhood. The architecture and ceremony of the memorial tomb therefore articulate a contradiction. They stake a claim on a language of familiarity and intimacy, even as they refuse to recognize its place in everyday life.

Thirty-four years after its completion, the Kocatepe Mosque responds to the challenge of the memorial tomb by addressing precisely this contradiction, but only to invert its terms rather than resolve it. The mosque is understood to represent a yearning for growing and uniting that is coursing through the entire nation. This interpretation on the part of both my hosts and their brochure depends on two thoughts, neither of which was entirely in place before the founding of the Turkish republic.

First, the Kocatepe Islamists identify the performance of Islamic beliefs and rituals with a desire for interpersonal association rather than primarily with believer, divinity, and cosmos. That is to say, religion now refers, as it never did before, to the experience of personhood through sociability. In effect, the Kocatepe Mosque stakes an Islamic claim on popular intersubjectivity in everyday life.

Second, the Kocatepe Islamists also impute to the nation a desire for intimate association. That is, they conceive of a mass society of anonymous others in terms of the experience of personhood through sociability. In doing so, they recognize the existence of a mass society, but they understand it in terms of circuits of interpersonal exchange rather than recognize it for what it is.

The two monuments are locked in an argument for sovereignty over a psychic terrain. The one poses the problem that a mass society of anonymous others represents for a language of familiarity and intimacy; the other reacts to the absence implicit in this formulation with an impossible figure of nationhood as desire for association.

Endnotes

Note 1: In the spring of 1994, large crowds gathered at the Atatürk Memorial Tomb to protest the defamation of Mustafa Kemal’s reputation by a member of the Welfare Party (Refah Partisi). Other officials of the party disowned these remarks and reaffirmed their respect for the founder of the Turkish republic. Back.

Note 2: See Jürgen Habermas, “Modernity: An Incomplete Project,” in Hal Foster, ed., The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, Port Townsend, Washington: Bay Press, 1983, 13. In reference to the nation-states of western Europe, Habermas differentiates “the project of modernity” from “the vital heritages of everyday life.” See also Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, vols. 1 and 2, New York: Vintage Books, 1945. His account of the United States is divided into a study of institutions, laws, and government (vol. 1) and a study of intellectual movements, personal sentiments, social mores, and political society (vol. 2). See also Serif Mardin, Religion and Social Change in Turkey: The Case of Bediüzzaman Said Nursi, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989, 163–64. He differentiates two levels of late Ottoman thinking: concepts of state institutions and social orders and concepts that consisted of a “personalistic view of society.” I have also relied on the discussion of the nationalist imagination in Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London: Verso, 1983, and the discussion of circuits of interpersonal exchange in James Siegel, Solo in the New Order: Language and Hierarchy in an Indonesian City, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986. Back.

Note 3: For a brief foray into this problem, see my “Oral Culture, Media Culture, and the Islamic Resurgence,” in Eduardo Archetti, ed., The Anthropology of Written Identities, Oslo: Scandinavian University Press, 1994. Back.

Note 4: By this explication, the akil is not really equivalent to the faculty of reason, calculation, imagination, or fantasy (although the same Turkish word can be used in most, if not all, of these senses). In contrast to these more active concepts of mental function, the akil (in the specific sense of the word that I am using here) is a passive, if not entirely perceptive, faculty that points toward the existence of externally imposed constraints. Back.

Note 5: Sultan and vizier stories are still told in the Turkish republic. I have heard many of them in the province of Trabzon since my first visit in 1965. Warren S. Walker and Ahmet E. Uysal recorded a number of such stories, including the one cited here; see their Tales Alive in Turkey, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1966. Many sultan and vizier stories have probably not changed significantly since the collapse of the old regime, but they have more or less lost whatever political bite they may once have had. Back.

Note 6: Walker and Uysal provide two variants of this kind of tale. The first was collected in the kaza of Ceyhan (Adana) during 1962, and the second, in Iskenderun (Hatay) during 1962. See their Tales Alive in Turkey, 142–43. Back.

Note 7: Gülru Necipoglu, “The Formation of an Ottoman Imperial Tradition: The Topkapi Palace in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries,” Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 1986; Gülru Necipoglu, Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power: The Topkapi Palace in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, Boston, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1991. Back.

Note 8: Necipoglu, Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power, 66. Back.

Note 9: Necipoglu, Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power, 65–66. Back.

Note 10: Stories that tell of Nasrettin Hodja’s encounters with Tamerlane, the great conqueror of the Turko-Mongol world, are exceptions to this rule. Back.

Note 11: See the many examples of this association in the stories presented by K. R. F. Burrill, “The Nasrettin Hoca Stories: An Early Ottoman Manuscript at the University of Groningen,” Archivum Ottomanicum, vol. 2, 1970, 7–114. Back.

Note 12: The text is an English translation of the Turkish given by P. Wittek, Turkish Reader, London: Percy Lund, Humphries & Co., 1945, 21. Back.

Note 13: Süleyman Ates, Muhtasar Islam Ilmihal, Ankara: Kiliç Kitabevi, 1972. Back.

Note 14: Ates, Muhtasar Islam Ilmihal, 50. Back.

Note 15: Ates, Muhtasar Islam Ilmihal, 53. Back.

Note 16: Ates, Muhtasar Islam Ilmihal, 54. Back.

Note 17: ernard Lewis, The Emergence of Modern Turkey, New York: Oxford University Press, 1961, 253–54. Back.

Note 18: Lewis, The Emergence of Modern Turkey, 256, 260. Back.

Note 19: Lauro Martines, Power and Imagination: City-States in Renaissance Italy, New York: Knopf, 1979, 275. Compare his assessment of the shift from late medievalism to early modernism in Renaissance Italy of the fifteenth century: “The quest for the control of space in architecture, painting, and bas-relief sculpture was not [merely] analogous to a policy for more hegemony over the entire society; it belonged, rather, to the same movement of consciousness.” Back.

Note 20: The competition for the design of the memorial tomb was opened on March 1, 1941, and closed on March 3, 1942. The forty-nine entries included teams from Turkey (20), Germany (11), Italy (7), Austria (7), Sweden, France, and Czechoslovakia. The international jury awarded three first prizes, to entries submitted by a German (Kruger), an Italian (Foshini), and two Turks (Onat and Arda). See Necdet Evliyagil, Atatürk ve Anitkabir, Ankara: Gazetecilik ve Matbaacilik Sanayii, 1988, 50. Back.

Note 21: Üstün Alsaç, “The Second Period of National Architecture,” in Renata Holod and Ahmet Evin, eds., Modern Turkish Architecture, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984, 99–100. Alsaç (94–96, 100–1) observes that the memorial tomb, as it evolved during its construction, came to feature both “national” and “modern” elements. The tomb was first designed during a resurgence of nationalism as economic crisis forced Turkish architects to turn to regional building materials and methods of construction. But it was completed over a decade later, after a series of redesigns, when Turkish architects were beginning to favor internationalism once again. The categories of “national” and “modern” are puzzlingly opposed in Turkey. By “national” (a category that was itself thoroughly modernist in character), Alsaç is referring to those traditional materials, designs, or structures that had come to signify a Turkish “folk” or “people” for the Turkish nationalists. By “modern” (a category that is otherwise closely associated with nationalism), he is referring to materials, designs, or structures that were recognized in Turkey as international and therefore not specifically Turkish in character. Back.

Note 22: See Evliyagil, Atatürk ve Anitkabir, 37–49. Back.

Note 23: Over the years, the memorial tomb came under the control of military authorities. After its construction by the Ministry of Transportation, it was administered by the Ministry of Education (from 1956) and then by the Ministry of Culture (from 1970). After the military coup of 1980, it was taken over by the Ministry of the General Staff (from 1981) to be administered in the name of the Memorial Tomb Command (from 1982). See Evliyagil, Atatürk ve Anitkabir, 67. All the presidents of military background have been buried at the memorial tomb, but not the two presidents of civil background, Bayar and Özal. Two days after his death on December 12, 1973, Ismet Inonü, “comrade in arms,” “the second president,” and “founder of democracy,” was buried at the memorial tomb just across from the great square, facing in a direct line bisecting the Hall of Honor. See Evliyagil, Atatürk ve Anitkabir, 65. Back.

Note 24: Since the Hall of Honor was not completed as originally planned, the resemblance is not plainly apparent. Back.

Note 25: For example, Evliyagil, Atatürk ve Anitkabir, 85, includes a picture of the Monument to the Martyrs at Çalköy in which Atatürk’s eyes appear clearly between the clouds above the site. Moreover, there is a moment during occasions of state when officials inscribe personal messages to Atatürk in a ledger. Back.

Note 26: Figure 10.3 is adapted from the brochure Anitkabir: Devrim Gençligi Ilavesi, Basvekâlat Devlet Matbaasi, n.a., n.d. This is a free handout that includes maps of the procession and burial ceremony held in 1953. The original figure illustrates how the officials and delegations that I have listed are assigned specific stations during the funeral ceremonies. The brochure, which must have been first published in the 1950s, was still available at the memorial tomb in 1987. Back.

Note 27: In 1853, the Topkapi Palace was abandoned as a residence, and the government was moved to Dolmabahçe Palace. Necipoglu, Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power, 258. Back.

Note 28: The criteria laid down at the time of the design competition in 1941 are more or less sufficient to account for the similarity between the memorial tomb and the Topkapi Palace: (1) The tomb will be a place of visitation. Visitors will enter a large hall of honor in the presence of the Father (Ata); they will stand before Atatürk and offer him their respects. (2) The tomb will represent Atatürk’s practical and creative qualities as a soldier, head of state, politician, and scientist. (3) The design of the memorial tomb should be such that its appearance is striking both close up and at a distance. Architectural motifs will be realized in the form of works that will express its power. (4) So that the Turkish state under Atatürk’s name and personality are symbolized, those who want to demonstrate their respect for the Turkish nation will manifest these feelings by bowing before the tomb of Atatürk. (5) A large Hall of Honor will be located on the site of the memorial tomb and visitations will be made at this hall. See Evliyagil, Atatürk ve Anitkabir, 50. Back.