|

|

|

|

Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey

University of Washington Press

1997

9. The Predicament of Modernism in Turkish Architectural Culture: An Overview

In 1930, the arrival of the modern movement in Turkey was celebrated in the official republican daily Hakimiyet–i Milliye: “In the last few years, the new architecture of the new age has been forming in all parts of the world. Young architects are breaking through old mentalities and traditions and marching toward the truth. We are proudly happy that some of the new construction in Ankara is a manifestation of this new architecture.” 1 The basic principles of this yeni mimari (new architecture), as the modernist avant–garde was then called, were captured in three words: rationalism, functionalism, and simenarme (reinforced concrete), uttered with all the quasi–religious zeal and optimism of Kemalist “nation building,” in both the literal and the metaphorical senses of the term.

Today, with no traces of this optimism left, the public and the architectural establishment in Turkey are lamenting the irreversible destruction of cities by reinforced concrete atrocities and by the sheer ugliness of the vast majority of new buildings, compared with the superior aesthetic qualities of the Ottoman heritage. At the same time, faced with its impotence to control the economic, social, and political forces behind this aesthetic degradation, the architectural profession is retreating to its more conventional preoccupation with form making, surrendering any larger mission of transforming society. As a panacea for the havoc wrought by sixty years of modernism, many Turkish architects in the 1980s have replaced the spirit of celebration that accompanied the arrival of the modern movement in the 1930s with an enthusiastic reception of the formalist, historicist, and eclectic experiments of postmodernism.

In this overview, I suggest that a less polemical and more fruitful approach to the predicament of modern architecture in Turkey, and elsewhere, would be to abandon the binary logic of modern versus postmodern altogether and face the historical complexity and ambiguity of the project of modernity in architecture. The central intellectual dilemma in many disciplines today is how to rely on the post–structuralist critique of Enlightenment values (and from that, on the post–Orientalist/postcolonial critique of the “Western canon” in art and culture) and yet invoke some of the same emancipatory and humanist values in order to engage with authoritarian political and cultural structures. 2 This dilemma preoccupies those of us in the discipline of architecture in our own way. We are all critical of the universalistic claims and totalizing discourse of high modernism, yet few of us can deny the initial critical force, democratic potential, and liberating premises of modern architecture as it emerged historically in Europe at the beginning of the twentieth century.

It was, after all, the pioneers of modernism who first installed issues of dwelling, housing, urbanism, and production as the legitimate and primary territory of architecture and who, indeed, wished to replace the preceding “architecture of historical styles” with “a new culture of building.” 3 This was hoped to be a new culture in which form would not be stylistically a priori but would result from considerations of program, function, site, practicality, simplicity, economy, materials, and rational construction. It would be, by definition, an architecture appropriate to its cultural and national context, varying in appearance from place to place but universal in the principles of design thinking that informed it. In the famous dictum of the modernist architect Bruno Taut, to whom the education of young Turkish architects was entrusted in 1936, “all nationalist architecture is bad, but all good architecture [read, modern] is national.” 4

It was implicit in this early modernist conception that the modern project in architecture was not only “unfinished” but should have remained so by definition, always resisting self–closure into orthodoxy and continuously rethinking its own premises in the light of new developments and new contexts. By the 1930s, however, the self–closure had already occurred. The modern movement in architecture was “invented” and codified as a unified formal canon (the so–called “international style” of white cubic forms, reinforced concrete, and glass) and as a thoroughly rational doctrine expressing the zeitgeist of the modern age. 5 For some time now, critics and revisionists in the historiography of modern architecture have compellingly argued that the reduction of modernism to a formal or stylistic canon and a scientific doctrine is a contingent historical phenomenon that needs to be carefully dissociated from the explicitly antistylistic and critical premises of early modernist thinking. Nonetheless, an uncritically construed and drastically reduced “modernist evil” has long been a convenient straw man for postmodernist attacks in the architectural culture at large, with an especially strong appeal outside the Western world, parallel to a mounting obsession with identity.

I argue in this essay that in Turkey, the truly critical and creative potential of modern architecture was compromised from the beginning because it was introduced to the country from above (and from without) as one aspect of the official program of modernization and was inscribed within the official cultural politics of the nation–state. Indeed, over the years, “modern architecture” has come to be equated exclusively with modern forms, and its legitimacy has been posited less in terms of its critical force to transform the discipline of architecture from within than in terms of its status as the bearer of the republican project, often in reference to ideologically charged polarities that are no longer tenable—for example, modern as opposed to traditional, and therefore progressive as opposed to reactionary. Especially after the Second World War, coinciding with the heyday of modernization theories in the social sciences, the notion of “modern architecture” was taken for granted as synonymous with the official high modernism of the West in its most sterile formal manifestations (boxes of glass and concrete), simplistic slogans (“radical break with history”), and universalizing claims (e.g., form as a thoroughly rational consequence of function and technique).

In what follows, I look at the predicament of architectural modernism in Turkey in three periods, each lasting about a decade and each bearing the legacy of a leader under whom the urbanscape and architectural culture of the country were dramatically transformed—namely, the founder of the republic, Kemal Atatürk, in the 1930s, Prime Minister Adnan Menderes in the 1950s, and the late President Turgut Özal in the 1980s. The central argument underlying my historical overview is that if modernism can once again be thought of as a critical, pluralist, inclusive, antistylistic, formally indeterminate discourse grounded in the historical condition of modernity and irreducible to any official style or doctrine, then it will be seen already to have much in common with the recent critique directed at the formal sterility, semantic poverty, and instrumental rationality of high modernism. In other words, it is theoretically possible to hold onto the programatic and democratizing content of modernism in architecture while rejecting its totalizing discourse of universal rationality. A modernist critique of what has been done in the name of modernism is, I believe, still a viable—and perhaps the only meaningful—way out of the current architectural impasse without necessarily endorsing either of the two currently popular options that postmodernism, as a stylistic trend in architecture, seems to offer: a “return to tradition” or the “global theme park.”

Modernism and Kemalism: The 1930s

Any discussion of modern architecture outside the West has to proceed from the premise that it was typically introduced in the conspicuous absence of all the conditions under which Western modernism flourished—especially the industrial city, capitalist production, and the autonomous bourgeois subject. It was therefore not grounded in a radical rethinking of the discipline of architecture in the context of profound historical, social, and technological transformations. Rather, it was primarily a form of “visible politics” or “civilizing mission” that accompanied official programs of modernization, imposed from above and implemented by the bureaucratic and professional elites of paternalistic nation–states.

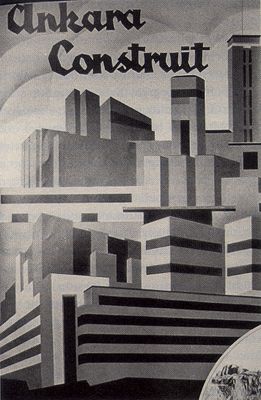

It is precisely such historical circumstances that underlie the paradoxical nature of nationalist discourses of modernity outside the West and the inherent ambivalence of architectural modernism as an expression of this paradox. 6 Epitomized by the Kemalist aspiration “to be Western in spite of the West,” Turkish architectural culture of the 1930s adopted the formal and scientific precepts of Western modernism and yet posited itself as an anti–imperialist, anti–Orientalist, and anticolonialist expression of independence, identity, and subjecthood by a nation hitherto represented only by the Orientalist cultural paradigms of the West. This profound ambivalence in the Kemalist project of cultural and architectural modernism, frequently overlooked in the postmodern tendency to focus only on its “colonizing” effect upon its own traditional population, is not unlike that of Salman Rushdie’s postcolonial immigrant in a Western metropolis, whom the author describes as “a disguise [inventing] his own false descriptions to counter the falsehoods invented about him” and therefore representing heroism as much as pathos. 7 It is this “heroic” aspect that comes across most forcefully in representations of the construction of Ankara as the modern capital of Kemalist Turkey in the 1930s—in one case, an architectural collage showing a futuristic city of abstract, purist buildings reminiscent of the tectonics of the Russian constructivist avant–garde (fig. 9.1).

|

| 9.1. “Ankara Construit.” (Reproduced from La Turquie Kemaliste, Ankara, 1935.) |

That modern architecture was instantly identified as “cubic” (kübik mimari) when it “arrived” in Turkey alongside the Westernizing institutional reforms of Kemalism bears testimony to the priority of exterior form during this period, a priority to which architectural culture, by its very nature, was among the most vulnerable. The novelty and revolutionary rhetoric of cubic or prismatic forms, reinforced concrete construction, wide terraces, cantilevers, and flat roofs, all without historical references, conveniently complemented the Kemalist “revolution” (inkilap), symbolizing the country’s emergence from “Oriental malaise” (sarkliliktan kurtulmak) and its willingness to participate in “contemporary civilization” (asrilesmek). 8 An article in the 1933 issue of Mimar, the new professional journal of Turkish architects in the republican period, juxtaposed the caption “Mimarlikta Inkilap” (revolution in architecture) with the canonic Villa Savoie of Le Corbusier, the brainchild of the modernist avant–garde, thus explicitly associating it with the Kemalist revolution, “in need of its appropriate architectural expression.” 9

Above all, yeni mimari, the new architecture, effectively legitimized the architect as a “cultural leader” or an “agent of civilization” with a passionate sense of mission to dissociate the republic from an Ottoman and Islamic past. Furthermore, the scientific claims of official modernism, grounded in doctrines of rationalism and functionalism, were especially favorable to the espoused positivism of the Kemalist project, lending credibility and authority to the expertise of an emerging architectural profession. In the minds of young Turkish architects there was no doubt that the nation–state was the bearer of modernity, and hence the formal and scientific precepts of official modernism, well established in Europe by the 1930s, were the most appropriate and progressive expressions of this unifying national ideal. The propaganda function of the modernist aesthetic was most conspicuous in buildings designed for national education and public indoctrination, such as schools and “Peoples’ Houses” (Halkevi), as well as in exhibition spaces such as the Izmir International Exposition buildings and the paradigmatic Sergi Evi, or exhibition hall, in Ankara (fig. 9.2). 10

|

| 9.2. Sergi Evi (Exhibition Hall), Ankara, 1933. (Postcard in the author’s personal collection.) |

The proliferation of images during this period and the formation of what may be seen as a “republican visual culture” (such as paintings depicting scenes of the Kemalist “cultural revolution,” posters by the prolific graphic designer Ihap Hulusi advertising products of national industry, and the photographs in La Turquie Kemaliste) was also instrumental in establishing modernism as primarily an aesthetic discourse. In spite of the arbitrariness of associating both the cultural and the scientific agenda of Kemalism with specific modern forms, the net result of this history has been an essentially formalist understanding of the term “modern architecture” rather than a deeper awareness of its critical content, and, in turn, a widespread identification of these forms with the secular nationalism of the republic. This tendency to charge architectural forms ideologically and to lose sight of their basic autonomy vis–à–vis politics has unnecessarily politicized and polarized the architectural culture in Turkey, even to this day, between a stubborn and uncritical defense of “modern architecture,” equated with defending the republic, and its indiscriminate condemnation as the built legacy of a mistaken era. What is frequently overlooked in this partisan polemic is that the architectural forms condemned as “modern” are merely images of modernism without the substance of modernity.

Most importantly, the inadequate resources of the country, especially the poverty of the construction industry in the 1930s, ruled out any substantial program of housing, urbanism, and rationalized production—the very basis of the democratic vision of the modernist utopia that sought to empower people in the politics of daily life. Unlike the extensive housing programs of the Weimar Republic in Germany, for example, which were an inspirational model for modernist discourse everywhere, including that of Turkish architects, actual building in the specifically and paradigmatically modernist category mesken mimarisi (architecture of the house/dwelling) was limited to a handful of villas and urban apartments for the republican elite, reinforcing that category’s associations with official culture and its popular perception as “alien” and “imposed.” Indeed, by the late 1930s, after a period of fervent controversy over the term kübik (cubic), 11 the “coldness and sterility” of such forms were rejected as the expression of an alienated, cosmopolitan society—of modernity in the most negative sense.

On the other hand, the rejection of kübik in favor of forms inspired by traditional Turkish houses, and the resulting search for a “national” style under the leadership of the prominent architect Sedad Hakki Eldem, was not necessarily a rejection of modernism as architectural historians have typically suggested (thereby betraying their own formalist–stylistic understanding of the term “modern architecture”). Eldem’s own admission that he “discovered” the Turkish house in Europe, through the principles of Le Corbusier and the drawings of Frank Lloyd Wright’s prairie houses in the United States, 12 reveals the essentially modernist spectacles through which he viewed tradition, however passionately he expressed this view in the nationalist rhetoric of the 1930s. What it also reveals is that, in spite of its own slogans and oversimplifications to the contrary, modernism is not a matter of form and is not necessarily antagonistic to tradition.

Finally, it should be noted that the buildings of the 1930s exhibit an architectural quality and care unmatched by subsequent architectural production. So far as the idea of the house is concerned, for example, the irony of modern architecture in Turkey is that the authoritarian and etatist early republican period produced the detached villa and row–house types (following European models of the same period that are still highly desirable environments when maintained and landscaped), whereas the relatively more liberal period after 1950 witnessed the introduction of high–rise slab block construction, the notorious symbol of the sterility, banality, and repetitiveness of high modernism or “international style” as it proliferated in every country after World War II.

“International Style” in Turkey: The 1950s

Marshall Berman’s account of twentieth–century modernism as a “flattening of perspective”—as modernity losing sight of its own origins and its own profound ambivalence over a simultaneously liberating and alienating historical possibility—is especially relevant for architectural culture in the 1950s.13 The hygienic, scientifically controlled, rationally ordered urban utopias that early modernists had projected as reactions to the social and environmental ills of the nineteenth–century industrial city (its congestion, pollution, degradation of workers, etc.) themselves became the established norm in planning. The cosmopolitan messiness, mixed–use patterns, and collective memory of Baudelaire’s Paris, the very locus of nineteenth–century modernity and urban life, were radically disrupted by the reductive and sterilizing principles of high modernist urbanism, informed by and operating with a relentless instrumental rationality. Especially after World War II, in an all–encompassing zeal for urban renewal and postwar reconstruction, the principles of modern urbanism—rational planning, functional zoning, the cutting of wide thoroughfares and traffic arteries through historical fabrics, the repetitive boom of high–rise housing blocks, and so forth—were applied on a large scale by Western, socialist, and Third World governments alike, with well–known disastrous results.

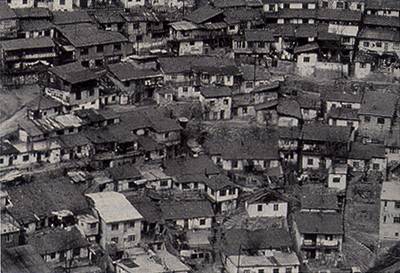

In Turkey, the elections of 1950 marked not only the end of the early republican era and the beginning of the more liberal economics and populist politics of the Democrat Party but also the unleashing of high modernism in architecture and urbanism. The extensive urban interventions carried out in Istanbul in the 1950s (fig. 9.3), a major project of political legitimacy and public relations under the personal directive of Adnan Menderes, constitute the closest Turkish counterpart to the modernism of Robert Moses, which Marshall Berman describes. The Beyoglu–Pera district of Istanbul, the city’s nearest equivalent to Baudelaire’s Paris, declined dramatically during this period, following the exodus of its non–Muslim population. At the same time, the phenomenal urbanization unleashed by massive migration from rural areas and the concomitant growth of squatter settlements around major cities (fig. 9.4) brought a much larger population into the ambivalent experience of modernity—that is, its seemingly endless possibilities, lifestyles, aesthetic norms, and high cultures, as well as people’s simultaneous awareness of their own exclusion from these things. One could say that while modernism as a political project reached its epitome in this period, it also became transparent as an irreversible historical condition.

|

| 9.3. Demolition and urban renewal in Istanbul in the 1950s. (Photograph by Ara Güler; reproduced from Istanbul, 6 July 1993.) |

|

| 9.4. Squatter settlements on the urban fringes of Ankara. (Photograph by M. Pehlivanoglu, Archives of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.) |

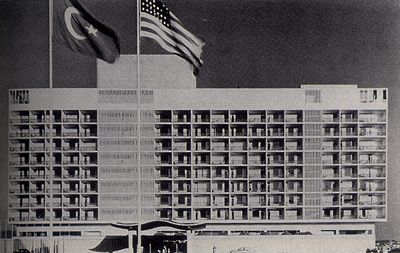

During the 1950s, the flow of foreign aid to Turkey, the arrival of Western experts from various international organizations, and Turkey’s aspiration to become “the little America” accelerated the dissemination of precepts of the “international style” in architecture and its wide acceptance by the country’s professional establishment. It is enough to note that even an architect like Sedad Hakki Eldem, who advocated a state–sponsored “national” style in the 1930s and 1940s, later became the local collaborating architect for the Hilton Hotel in Istanbul, the hallmark of “international style” in Turkey designed by the corporate firm of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill (fig. 9.5). Many examples and variants of this corporate style, with its concrete slabs and glazed skin surfaces, were designed by prominent Turkish architects throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

|

| 9.5. Hilton Hotel, Istanbul. Architects Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill; local consultant Sedad Hakki Eldem, 1952. (Reproduced from “Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill,” Aga Khan Program at MIT, n.d.) |

The high–rise slab block model for housing was introduced to the country during this period, too, under the initiative of the Emlak Kredi bank. The bank was originally established to provide long–term, low–interest credit to alleviate the drastic housing shortage accompanying rapid urbanization. It ended up financing examples like the Levent and Ataköy housing blocks in Istanbul that were far from being subsidized, low–income housing, turning instead to upper–class apartments. At least these early examples followed the modernist emphasis on rational design, sun angles, ventilation, and greenery (fig. 9.6). In contrast, lesser examples of high–rise slab block construction on narrow urban lots multiplied rapidly during the speculative apartment boom of the following decades, replacing architectural concerns with the priorities of the developer and reaching a level of “visual contamination” that has bred today’s reaction (fig. 9.7). What is frequently forgotten in hasty denunciations of modern architecture is that there is no necessary link between the architectural precepts of modernism and all the negative consequences of condominium legislation (kat mülkiyeti kanunu), a speculative market in developer–initiated housing, and planning codes that do not lend themselves to experimentation with more appropriate urban alternatives such as low–rise, high–density housing or perimeter block construction.

|

| 9.6. Ataköy housing, Istanbul. (Courtesy Ataköy Planning Office, Archives of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.) |

|

| 9.7. Proliferation of concrete slab block apartments in Istanbul. (Photograph by the author.) |

From the late 1960s onward, however, as the architectural culture at large embarked upon a critique of the environmental and social failures of “high modernism,” architectural discourse in Turkey also expressed increasing discontent with the legacy of the 1950s–the overwhelming aesthetic invasion of major cities by concrete–frame, slab block apartment construction and the destruction of historical fabrics by large–scale urban interventions. 14 What is important to note, however, is that none of this critique was yet formulated in explicitly anti– or postmodernist terms, and the word “postmodernism” in architecture, adopted by Charles Jencks in 1977, 15 was not yet in favor or wide circulation among Turkish architects.

Indeed, discontent with the architectural and urban effects of modernization was being voiced precisely at a time when, perhaps for the first time since the republican project of modernization was proclaimed, the liberating promise of modernity was also being felt by masses of people attracted by the richness of life and opportunity in urban centers. The consensus within the professional and educational establishment was toward mitigating the negative consequences of architectural high modernism by fragmenting its boxy aesthetic into modular systems or organic forms, replacing its slick surfaces of glass and plastered concrete with the more textured surfaces of the “new brutalism” of exposed concrete, brick, and wood, and revising its universalistic formulations with regionalist overtones. The Turkish Historical Society building in Ankara, designed by Turgut Cansever, and the Social Security complex in Zeyrek, Istanbul, designed by Sedad Hakki Eldem, can be cited as successful examples of such unorthodox modernism in the 1960s (fig. 9.8). At that particular point in history, Eldem had dropped the nationalist rhetoric he had attached to his architecture in the 1930s and 1940s, and Cansever had not yet resorted to Islamic cosmology and “return to tradition” to explain the qualities of his work.

|

| 9.8. Social Security complex, Zeyrek, Istanbul, 1962–64. Architect Sedad Hakki Eldem. (Photograph by A. Dündar, Archives of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.) |

Today, by contrast, blaming the contemporary plight of architecture and urbanism on the humanism of the Renaissance and the instrumental rationality of modernism, Turgut Cansever portrays Islam not only as the source of his architecture but also as the only significant basis of resistance to the culture of consumption, instant gratification, and rampant economic injustice in Turkey in the 1980s. 16 What gets lost in his words is that it is essentially from a sensitivity to place, craft, texture, light, site, and topography that his work derives its quality and poetics. His highly acclaimed Demir Holiday Village in Bodrum, constructed in the stone vernacular tradition of the Mediterranean, is frequently portrayed as a symbol of the triumph of tradition over the contentious history of modern forms. Beyond the polemics, however, this building, like many other examples of “critical regionalism” (i.e., context–sensitive modernism) everywhere, is simply good architecture (which is frequently limited to well–crafted individual houses for well–off clients) that cannot be explained by Islam or tradition or, for that matter, region or culture alone. 17 Cansever’s case, like that of Sedad Hakki Eldem before him, bears testimony to the predicament of modernism in Turkey, which is the recurrent habit of enframing architecture within some kind of identity politics —nationalism, or “Turkishness,” for Eldem, and Islam and tradition for Cansever—even though there is ample evidence that at its best, modern architecture resists all the essentialist claims to identity that supposedly inform it.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, intellectuals and the highly politicized Chamber of Architects leaned toward Third World–ist versions of modernization, looking no longer at the West but at squatter houses and folk architecture and shifting their emphasis from the aesthetics of architecture to the politics of production processes. Thus they also triggered growing academic interest in squatter settlements as an alternative social and architectural process outside the domain of both the state and the profession. Ideas about participatory and democratic design processes in housing, especially the possibilities of self–help schemes (combining the provision of preliminary design, infrastructure, and services at the professional level with the local resources and labor of the squatter populations), began to make their way into the discourse of the discipline and into architectural schools, if not into actually implemented examples.

In contrast, the current sense of the impotence and irrelevance of architecture in engaging with these issues has effectively surrendered the ground to a phenomenally unchecked and unplanned speculative development of cheaply built, substandard housing inhabited by second– and third–generation squatters. It may not be too farfetched to claim that in the late 1960s and early 1970s there was a moment for a critique of high modernism in architecture from within modernist premises—a brief moment that was rapidly lost in the political, economic, and cultural climate of the 1980s.

The Panorama of Postmodern Turkey: The 1980s

The defining feature of “postmodern” Turkey in the 1980s can be summed up as a growing reaction to the official ideology, cultural norms, and mental habits of the old republican elite, as well as of the traditional left, by groups ranging from advocates of liberal economy, civil society, popular culture, and feminism to Muslim intellectuals. The austerity and paternalism of official modernism were challenged in all expressions of culture, from literature and music to architecture and cinema.

In economic and political terms, this reaction bore the legacy of figures such as Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and the late Turkish president Turgut Özal, and it marked the historical end of nationalist developmentalisms everywhere. 18 In cultural terms, it was marked by a radical departure from the universalistic claims of modernization theories in favor of a new emphasis on cultural identity and difference, prompting even the old guard of well–established modernist architects in Turkey to experiment with historicist and vernacular forms and at times even to pay lip service to Islamic quotations. The embracing of the term “postmodernism” in the 1980s by the architectural establishment throughout the world coincided with the new economic, political, and cultural developments and frequently obscured the crucial distinction between the critical dimension of postmodernity and its co–option into a justificatory stylistic trend in architecture. 19 While the critical dimension prompted everyone to question the assumptions of official culture and high modernism rather than taking them for granted, among architects it also led to a de facto legitimization of the stylistic trend.

The cultural expressions, construction boom, and changing urbanscape of the Özal years in Turkey bore ample witness to this ambivalence of the postmodern moment. On one hand, in a potentially democratic impulse, educated elites became increasingly more aware of the multiplicity of taste cultures, and especially of popular culture as the manifestation of the struggle of marginalized peoples for cultural expression and self–representation. We all began learning to suppress our contempt for gecekondu taste, arabesk music, kebab houses, intercity bus terminals, and cheap little mosques with aluminum domes, if we did not actually begin rather to like them, as we confronted our own ambivalent experiences of modernity.

Today, the elitism, austerity, and paternalism of the official modernism of the republic are increasingly unpopular, and so is the avant–garde theory of false consciousness that gives the traditional elites the right to redeem the masses in their name. Of course, where to draw the line between this democratic impulse and what is essentially an endorsement of kitsch just because “it belongs to the people” (often the mark of an elite guilt consciousness) is a formidable question that we constantly confront, especially in an inherently elite discipline like architecture.

The case of the phenomenal increase in the number of badly designed and poorly built new mosques (often a mosque–office block–shopping complex) is a telling example. Treated with contempt by the architectural establishment, they testify to the overall environmental and aesthetic contamination brought about by economic, social, and political forces far beyond the control of the architectural profession. Yet they also bear testimony to the traditional failure or reluctance of the professional elite to treat the mosque as an important architectural type or design problem, thus surrendering it to the domain of the least educated and most populist groups in society. 20

On the other hand, it should be noted that the architectural establishment is celebrating what is perceived to be a “liberation” from the sterility and facelessness of international modernism, ironically and precisely at a time when the country has opened up to a further internationalized and globalized capitalism. 21 Most significant in architectural and urban terms is the proliferation of five–star hotels (Conrad, Swiss, Möwenpick, and Ramada in Istanbul; Hilton and Sheraton in Ankara), supermarkets and shopping malls (Ataköy Galleria and, more recently, Akmerkez in Istanbul; Karum and Atakule in Ankara) (fig. 9.9), business centers and glazed atria, and holiday villages connected to international chains (Club Med, Robinson, etc.). The latest examples of transnational postmodernism and “high–tech” expressionism are replicated by, mostly, a younger generation of architects, often with qualities comparable to those of their Western models. Although there is, admittedly, something refreshing about this reorientation of attention toward the discipline of architecture itself, rather than toward its political and economic context, it manifests itself as experiments in form and image making for private clients who can afford it, at the expense of the larger social agenda of modernism.

|

| 9.9. Karum shopping mall, Ankara. (Photograph by the author.) |

Complementing these trends, there is a hitherto unprecedented proliferation of glossy publications, design and decoration magazines, office supplies and professional tools—including sophisticated computer–aided design systems—and imported building materials, components, fixtures, and finishes, as well as their domestic imitations, with ever–improving marketing techniques. Looking at the advertisements in architectural magazines for space frames, precast or lightweight concrete components, or glass blocks (fig. 9.10)—that archetypal material of the early modernist aesthetic in Europe—one cannot help thinking that at the same time modern forms are being rejected, the material basis of a modernist aesthetic (that is, new materials informing the modernist aspiration for lightness, transparency, and standardization) is just emerging in Turkey. Perhaps more phenomenal in the residential patterns of the upper classes and the emerging “yuppies” is the move away from the city to villa–type developments such as Mesa Koru Sitesi in Ankara or Alarko–Alsit in Istanbul (fig. 9.11), or to exclusive new suburbs like Bahçesehir and Kemer Country outside Istanbul—complete with the cult of nature and health, swimming pools, tennis courts, golf courses, and horseback riding.

|

| 9.10. Advertisements for building materials, components, and fixtures, 1990s. (Reproduced from Arredemento Dekorasyon, no. 11, 1994.) |

|

| 9.11 Advertisement for duplex villas on Anadoluhisari, Istanbul. The caption reads, “Far from sight, close to your work!” (Reproduced from Kapris, 1987.) |

The case of Kemer Country, developed on a large site outside metropolitan Istanbul and surrounded by a belt of forest ten kilometers deep, is a particularly significant one. Publicity brochures and occasional newsletters issued since the inception of the enterprise in 1991 openly identify the scheme with the passionately antimodernist architectural discourse of the “traditional neighborhood development” promoted by Prince Charles (and his neoconservative architect Leon Krier) in the West. We are told that “Kemer Country is designed to revitalize an old lifestyle in which neighborhood (mahalle) was the keyword and we all belonged to our neighborhoods. The greatest problem of Istanbul today is not noise or pollution or traffic, nor is it congestion or high cost of living, all of which we cope with in one way or other. It is, instead, the loss of our sense of belonging, without which we cannot survive.” 22 Especially in the third phase of the development, the prominent Florida architectural firm of Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater–Zyberk were employed “to restore this lost sense of neighborhood.” The accompanying sketches depict villas inspired by traditional Turkish houses: tile roofs, modular windows, projecting bays on upper floors (cumba), courtyards (avlu), narrow streets (sokak) and small squares (meydan), to which the historical Ottoman aqueduct constitutes an appropriate backdrop (fig. 9.12).

|

| 9.12 Advertisement for the development project called Kemer Country. The title reads, “We now have a neighborhood.” (Reproduced from Newsletter of the Kemer Construction and Tourism Company, Winter 1994.) |

Kemer Country claims to represent the pragmatic design approach of “traditional neighborhood development” in which, after certain building codes and stylistic features are fixed as the basis of the “civic identity of the place,” the design process involves groups ranging from teams of designers to speculative developers, and from administrators and management consultants to prospective users. Although this in itself is an innovative approach with a democratic potential inconceivable under the authoritative idealism of the heroic modern architect, there is nothing in it that automatically leads to or necessitates the traditional, antimodern forms that Duany and Plater–Zyberk have produced in most of their schemes. In the last analysis, not unlike the modernism it vehemently condemns, the Kemer Country project still sets priority on exterior form, and in its antimodernist rhetoric it is no less ideological than modernism.

When all is said, behind the proudly “traditional” facades of Kemer Country—from Turkish vernacular to Tuscan villas and Georgian mansions —we find straightforward upper–class suburban villas with Jacuzzi bathrooms, basements, yards, and garages. What remains to be seen is whether reconstructing the physical fabric of the traditional neighborhood is indeed a restoration of the relationship between architecture and pluralist democracy, as is claimed by the Turkish developers of the scheme 23 (although who can claim that traditional Ottoman neighborhoods were “democratic”?), or, instead, an inevitably artificial “public realm” that, in claiming to restore a sense of belonging, still excludes many who do not belong there. That the prices of the fourteen different types of villas range from U.S. $350,000 to $2 million, not to mention the prerequisite of car ownership to live there, suggests the latter. Indeed, in many of these recent architectural developments in Turkey, from upper–class shopping malls to suburban villas behind well–guarded enclosures, there is a conspicuous erosion of accessible–to–all public space that is the hallmark of a real urban condition and real cultural and class diversity. 24 Notwithstanding its critique of the self–righteous republican elite, postmodernism in architecture continues to cater primarily to the exclusive lifestyle of a privileged elite—except this time it is an elite of industry, finance, and business that replaces the bureaucrats of the republic.

Conclusion: A Critical (Post)Modernism?

There is no question that in Turkey, as elsewhere, the postmodern critique in architecture has rightly questioned the aesthetic canon of official high modernism as well as the universalistic discourse, elitism, and instrumental rationality of its politics. Contrary to the claims of postmodernists, however, most of this critique is hardly new or, for that matter, incompatible with a critical modernism. The first and perhaps only point we can legitimately make about a critical modernism in architectural culture is that it would be self–defeating to codify it in a priori formal or stylistic terms. It is “radically indeterminate” in its forms, just like the project of democracy to which it is intimately connected. 25 Thus it is theoretically an “empty space” or “utopic void” that needs to be filled historically and contextually, not by ahistorical and essentialist truths, and not arbitrarily in the total absence of any truth. With significant implications for the recent identity consciousness in the architectural culture of non–Western countries, such a critical modernism is radically opposed to making identity politics the centerpiece of design, knowing that identities are always complex, shifting, and contradictory, always contesting the constructs that attempt to fix them.

On the other hand, the contingency of all truth claims and the possibility of alternative modernisms does not make them all equal or eliminate the mandate of educated elites, such as architects, to address problems and offer options, if not impositions. That the profession of architecture is radically challenged by recent developments in the world—on one hand, the computerization of design (the “anybody can design given the right software” argument), and on the other, the appearance of hitherto marginalized groups (the “canons of a discipline laid out by white, male, Western or Western–educated architects cannot respond to a pluralist society” argument)—does not necessarily render the profession obsolete, as some today would argue it does. It only gives the profession all the more reason to engage with these new challenges.

The forms and doctrines of the modernist utopia may no longer be tenable. Yet few would deny that its programmatic content—its preoccupation with issues of housing, urbanism, and building production, revised and enhanced by more recent concerns such as ecology, public space, and cultural diversity—”still matters” as far as the discipline and profession of architecture are concerned. 26 Any recent celebration of postmodernism in architectural culture as “the liberation of the discipline” would be incomplete without the larger picture, which depicts a drastically diminished role, relevance, and significance for architecture in the society at large. As Stuart Hall cogently puts it, “it is perfectly possible to invoke the postmodernist paradigm and not understand how easily postmodernism can become a kind of lament for one’s own departure from the center of the world.” 27

To conclude with the post–Enlightenment dilemma that I touched on in the beginning, the best we can hope for is continuously to sharpen our awareness of the inherent ambivalence of the initial modernist project, which was without doubt a political project (as postmodern criticism has exposed) but also, I would insist, a historical condition that has opened up possibilities far too rich to be reduced to the now–discredited political project. It is neither fair nor theoretically consistent to portray modernity only as an oppressive political project and, in opposition to this, celebrate postmodernity only as a historical condition with democratic and pluralist implications. At least in architecture, the reverse could be argued with equal conviction.

I have tried to suggest in this essay that, at least in my field, a more fruitful premise on which to pose the debate lies first in moving beyond reductionist and simplistic definitions of both modernism and postmodernism, dispensing with the notorious binary opposition set up between them largely for polemical purposes. Second, it is important to recognize the disciplinary autonomy of architecture, or of other forms of cultural production for that matter, whereby individual works, overdetermined by a multiplicity of factors both external and internal to the discipline, are as much products or expressions of the culture and politics of an era as they are possible sites of resistance to it.

Endnotes

Note 1: “Yeni Mimari: Mimarlik Aleminde Yeni Bir Esas” (New Architecture: New Principles in the Architectural World), Hakimiyet–i Milliye, 2 January 1930. Also important in the proliferation of the term “new architecture” was Celal Esat Arseven’s Yeni Mimari, Istanbul: Agah Sabri Kütüphanesi, 1931, which was based on Andre Lurcat’s Architecture, Paris: sans pareil, 1929. Back.

Note 2: This dilemma is expressed cogently by Tim Mitchell and Lila Abu–Lughod in “Questions of Modernity,” SSRC Newsletter, vol. 47, no. 4, 1993, 82. For an acknowledgement of this dilemma by Edward Said, the most prominent critic of the Western canon in art and culture, see his “Politics of Knowledge,” Raritan, Summer 1991, 17–31. Back.

Note 3: The distinction between the architecture of historical styles and the new antistylistic art/culture of building is captured, for example, by the title of Herman Muthesius’s Style Architecture and Building Art, translated by Stanford Anderson, Santa Monica, California: Getty Center, 1994 (originally published as Stilarchitektur und Baukunst, 1902) and expressed in different ways by many modernist architects of the early twentieth century. The same distinction between style architecture (üslup mimarisi) and building art (yapi sanati) permeated the discourse of Turkish architects in the 1930s. Back.

Note 4: Bruno Taut, Mimarlik Bilgisi (Lectures on Architecture), Istanbul: Güzel Sanatlar Akademisi, 1938, 333. Back.

Note 5: See Giorgio Cuicci, “The Invention of the Modern Movement,” Oppositions, no. 24, 1981, 69–89. Particularly instrumental in this construction of an official history for modern architecture was Philip Johnson and Henry–Russel Hitchcock’s The International Style: Architecture since 1922, New York: W. W. Norton, 1932, accompanying the famous Museum of Modern Art exhibition, and Siegfried Giedion’s Space, Time and Architecture, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1941. Back.

Note 6: The paradoxical nature of nationalist discourses outside the West is discussed by Partha Chatterjee, Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World, London: Zed Books, 1986. Back.

Note 7: Salman Rushdie, The Satanic Verses, Dover, U.K.: The Consortium, 1992, 49. Back.

Note 8: See my “Architecture, Modernism and Nation–Building in Kemalist Turkey,” New Perspectives on Turkey, no. 10, 1994, 37–55. Back.

Note 9: Behçet Bedrettin, “Mimarlikta Inkilap,” Mimar, 1933, 245. Mimar started its publication in 1931 and was renamed Arkitekt three years later. Back.

Note 10: The Sergi Evi building, designed by the Turkish architect Sevki Balmumcu, was later converted by the German architect Paul Bonatz into the State Opera and Ballet. The nature of this conversion, from a modernist aesthetic to a more austere and official building with “Turkish” details, illustrates the idological climate of the 1940s. Back.

Note 11: Best known in the literature of the period are the negative portrayals of a cubic house in Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoglu’s 1934 novel Ankara (Istanbul: Iletisim Yayinlari, 1991 [1934]) and of a certain “cubic palace” in Halide Edip Adivar’s Tatarcik, which was serialized in the popular weekly magazine Yedigün in 1939. Peyami Safa, in “Bizde ve Avrupa’da Kübik,” Yedigün, 14 October 1936, no. 8, 7–8, designated “cubic” as a disease “more dangerous than the fires that devastated the traditional houses of Istanbul.” Back.

Note 12: See Sibel Bozdogan et al., Sedad Eldem: Architect in Turkey, Singapore: Concept Media, 1987. Back.

Note 13: Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts into Air, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983. Back.

Note 14: The critique of “high modernism” especially followed the impact of Jane Jacobs’s seminal The Death and Life of Great American Cities, New York: Random House, 1961. Back.

Note 15: See Charles Jencks, The Language of Post–Modern Architecture, London: Academy Editions, 1977. Back.

Note 16: Interview with Turgut Cansever in Dergah, July 1991. Back.

Note 17: I use the term “critical regionalism” in the sense in which it is articulated by Kenneth Frampton, “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance,” in Hal Foster, ed., The Anti–Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, Port Townsend, Washington: Bay Press, 1983, 16–30. Back.

Note 18: On the end of nationalist developmentalism, see Çaglar Keyder, Ulusal Kalkinmaciligin Iflasi (The Bankruptcy of National Developmentalism), Istanbul: Metis Yayinlari, 1993, and also his “The Dilemma of Cultural Identity on the Margin of Europe,” Review, vol. 16, no. 1, 1993, 19–33. Back.

Note 19: On the embracing of the term “postmodernism” by the architectural establishment, see Mary McLeod, “Architecture and Politics in the Reagan Era: From Postmodernism to Deconstructivism,” Assemblage, no. 8, 1989. See also her chapter “Architecture” in Stanley Trachtenberg, ed., The Post–Modern Moment, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1985, 19–52. Back.

Note 20: For these points, and for a recent discussion of contemporary mosque architecture, see the writings by Dogan Kuban and Ugur Tanyeli in a special section titled “Contemporary Mosque Architecture” in Arredemento Dekorasyon, no. 11, 1994, 80–91. Back.

Note 21: For the urban and cultural expressions of this new atmosphere, see also Asu Aksoy and Kevin Robins, “Istanbul between Civilization and Discontent,” New Perspectives on Turkey, no. 10, 1994, 57–74. Back.

Note 22: Kemer Country, publicity brochure for the third phase of development, Istanbul, 1993. Back.

Note 23: “Zaman Ötesi’nin Pesinde Kemer Country” (In Pursuit of the Timeless: Kemer Country), interview with the developer, Esat Edin, and the design coordinator, Talha Gencer, in Arredemento Dekorasyon, no. 10, 1993, 121. Back.

Note 24: See Aksoy and Robins, “Istanbul between Civilization and Discontent.” Back.

Note 25: Here I am inspired by Chantal Mouffe’s discussion of “radical democracy” in her “Democratic Citizenship and the Political Community,” in Chantal Mouffe, ed., Dimensions of Radical Democracy, London: Verso, 1992, 225–39. The idea of maintaining the democratic and critical potential of modern architecture while rejecting its totalizing and universalistic discourse is analogous to Mouffe’s critiquing the epistemological project of the Enlightenment while maintaining its political project of democracy. See her collection of essays, The Return of the Political, London: Verso, 1993, especially her introduction, “For an Agonistic Pluralism,” 1–8. Back.

Note 26: See Marshall Berman, “Why Modernism Still Matters,” in Scott Lasch and Jonathan Friedman, eds., Modernity and Identity, Oxford: Blackwell, 1992, 33–58 Back.

Note 27: Stuart Hall, “The Emergence of Cultural Studies and the Crisis of the Humanities,” October, no. 53, 1990, 11–23. Back.