|

|

|

|

Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey

University of Washington Press

1997

7. The Project of Modernity and Women in Turkey

Professor Nermin Abadan–Unat is Turkey’s first female political scientist, an ex–senator, a promoter of women in academia, and a defender of women’s rights in Turkey and abroad. She was born in 1921 in Vienna to a German–speaking mother of Baltic origin and a Turkish fruit merchant from Izmir. She lived abroad until her father died, and then, when private education was becoming increasingly difficult for her mother to finance, she migrated—or rather, ran away—to Turkey to continue her education. She had heard that girls as well as boys could be educated for free in Turkey.

After she narrated this life story in her last lecture before retiring from the Faculty of Political Science at the University of Ankara in 1988, Professor Abadan punctuated her story by saying, “I chose my country as well as my nation with my own will. If Mustafa Kemal did not exist, perhaps I would not exist. I suspect now you have understood why I am a Kemalist, why I am a nationalist.” 1

At about the same time, Sirin Tekeli, a leading feminist activist, was publicly criticizing Kemalism. 2 Born in 1944 in Ankara, Sirin was the daughter of prototypical Kemalist intellectuals. Both of her parents were high–school philosophy teachers, and her mother, especially, was a fervent advocate of Kemal. Like Nermin Abadan–Unat, Sirin was a political scientist. After she became an associate professor in the Faculty of Economics at Istanbul University, however, she resigned from the university in protest of the Board of Higher Education established in 1981. 3 She helped organize feminists in Turkey and helped found the Women’s Library and Information Center in Istanbul. In an interview for a book on the left’s assessment of Kemalism, she explained,

It is true that the women’s revolution was a significant part of Kemalism. Our [feminists’] first question, however, is this: Was this revolution undertaken for women’s own rights or was it used in some manner for the other transformation, the transformation Kemalism aimed to accomplish at the level of the state. I solemnly believe there was such an instrumentality. Atatürk was a soldier and an excellent strategist. He was a person who could evaluate what women’s rights meant in the context of the transformation of the state. He was a Jacobin and he made use of women’s rights as much as he could. 4

Other feminists are more abrupt. They simply say they are not Kemalists and go on to elaborate why.

In this essay, I explore how women of one generation who, figuratively, owed their existence to Atatürk came to be challenged by a younger generation that radically criticized him. My purpose is to interpret the significance of the modernizing reforms in the context of this new challenge coming from the more radical feminist voices in the contemporary scene. What did the reforms of the 1920s bequeath to the 1980s? Do feminists who oppose the Kemalists undermine or revive the project of modernity the Kemalists initiated? With their demands for autonomy and subsequent criticisms of Kemalism, the feminists, I argue, paradoxically help further the project of modernity in Turkey. Feminist criticisms of Kemalist discourse attempt to free liberalism, democracy, and secularism from a polity that has long repressed those qualities in the name of those very qualities themselves.

Whereas women were essential “actors or pawns” in the republican project of modernity, 5 feminists are a small group in the contemporary scene. Carlos Fuentes, in The Buried Mirror, argues that “a constant of Spanish culture, as revealed in the artistic sensibility, is the capacity to make the invisible visible by embracing the marginal, the perverse, the excluded.” 6 The feminists are a marginal group, if not the perverse and the excluded, and focusing on their activism makes the invisible threads of the republican project of modernity—its goals, successes, and limits—visible. The emergence of feminism attests to the vigor of the modernist project. The project continues as it is liberated from the monopoly of Kemalist discourse and regenerated by a plurality of voices, including feminisms critical of Kemalist modernism.

I first examine how women helped construct the project of modernity, what Tekeli called “the other transformation at the level of the state.” I then try to reconstruct the challenge to that project coming from feminists. Finally, I evaluate the extent to which the feminist challenge undermines or revives the Kemalist project of modernity.

I use the term “feminist” to refer to those who identify themselves as such in pursuit of women’s liberation. During the 1980s, the older generation of Kemalist women identified themselves as egalitarian feminists or, at times, as Kemalist feminists. 7 When I use the term “feminist,” I mean the younger group who challenged Kemalism, and I call the other group egalitarian feminists.

The Kemalist Project of Modernity and the Female Cast

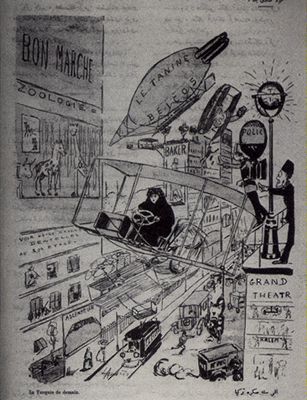

The cartoon reproduced as figure 7.1, titled “Turkey of the Future,” was published in the weekly Kalem in 1908, before the republic was founded in 1923. It depicts a woman aviator dressed in a traditional çarsaf, flying over a hectic urban street to the awed stares of onlookers. The mosques recede in the background, and tall buildings transform the Turkish setting into any “modern” Western one with skyscrapers and department stores.

|

| 7.1. “Turkey of the Future.” (Reproduced from Kalem, December 1908.) |

This 1908 vision was actualized both literally and figuratively in two or three decades in the early republican period. The change was greater than could have been envisioned in the 1900s. Women did not just fly but shed their çarsafs as well. Atatürk’s adopted daughter Sabiha Gökçen became the first military aviator in Turkey. The image of Sabiha Gökçen in her air force uniform, with respectful male onlookers, including her proud father, is ingrained in the collective consciousness of at least the educated urbanites in Turkey. Figuratively, if the project of modernity aimed for a Westernizing polity that was liberal, democratic, and secular, then a female aviator could herald all. This was a new image for Turkey, a new role model for the country’s women. A female military aviator insinuated nationalism (because the Turkish nationalist myth upheld male–female equality), democratic participation of women in the making of the new polity, and a secular ethos (because the Muslim opposition did not promote public activism of women). Turkey was taking wings to the future, with women playing leading roles.

The cartoon shown as figure 7.2, published in 1909 in the weekly Davul, can be read symbolically. The woman riding the bicycle in Western clothes symbolizes the tantalizing modernity that the West represents for the traditional Turkish man, who pursues her earnestly. With a fez on his head, the man in pursuit has the trappings of a gymnast on his legs, but the woman, in her Western–style evening dress, looks physically more fit. What is of the West is sound, fit, and ought to be pursued.

|

| 7.2. The caption for this cartoon reads, “A healthy mind is to be found in a healthy body; therefore, we should do sports.” (Reproduced from Davul, January 1909. |

By the 1990s, much has been said about the role women were made to play in the project of modernization in Turkey. Many have pointed to the instrumental nature of the modernizing reforms. 8 The adoption of the Civil Code in 1926 to replace the Shari’a was a severe blow to the Islamic opposition. The extension of suffrage to women in 1934 was an important move underlining the democratic aspirations of the new republic, despite its authoritarian practices. The principle of male–female equality was defended in the new republic with appeals to a golden Turkic past in Central Asia. 9 To the extent that the defense of women’s rights involved reference to the mythic Turkish past, they also provided occasion to reinforce that nationalist myth.

The republican fathers who initiated these reforms believed they knew the best interests of their polity, and these corresponded to the best interests of women in the polity. Atatürk could found the republic and claim, “Republic means democracy, and recognition of women’s rights is a dictate of democracy; hence women’s rights will be recognized.” 10 Similarly, he could say that “if knowledge and technology are necessary for our society, both our men and our women have to acquire them equally.” 11 Both quotations reveal not merely the instrumental, functional approach to women’s rights but also the certainty with which what was good for the other was assumed. What women wanted was not a problematical issue.

Hence, if the dictates of modernization required that women play not merely public roles but also traditional ones—but with a Western ethic—then they were encouraged to play these revised traditional roles. Yael Navaro draws our attention to the adoption of Taylorism in housework in the early republican era. 12 While the state encouraged increasing involvement by a group of elite women in public life, it sent a different message to an increasingly large number of “other” women: they were expected to contribute to the process of modernization not by becoming elite women professionals but by being housewives à la the West, bringing “order,” “discipline,” and “rationality” to homemaking in the private realm. Girls’ institutes founded under the Ministry of Education in 1928 and “evening girls art schools” (Aksam Kiz Sanat Okullari) that were later instituted served this purpose. 13 They channeled women to the task of “modernization” at home by applying the methods of Taylorism to housekeeping in Turkey.

While men may have found it expedient to redefine women’s roles in their project of modernization, at least a critical number of women did benefit from these changes and endorsed them earnestly. All reforms that helped secularize and Westernize the republic (including the elimination of the caliphate, or religious orders, the introduction of secular education, language reform, and the adoption of the Western calendar and metric system) encouraged women to play new public roles in society. They could now become professionals expected to be equal to men in the public realm, embodying the universal ideals of equality of humankind.

Women assumed their new roles with a vengeance. Theirs was a nationalist mission. They worked in service to the modernizing state, conscious of being women in the public realm and in line with the prevailing populist ethics. Hamide Topçuoglu, a vanguard woman professional, recalled that being a professional “was not ‘to earn one’s living.’ It was to be of use, to fulfill a service, to show success. Atatürk liberated woman by making her responsible.” 14 The purpose of the professional work expected of women was service to the modernizing nation. Women internalized this expectation and were proud to carry it out.

These professional women perceived themselves as representatives of Turkish woman, used in the singular without reference to regional or other differences. A disregard and distaste for difference was in harmony with the populist custom of the day, which assumed all existing cleavages to have melted in the nationalist pot. Thus Nakiye Elgün, a woman appointed as a representative to the parliament, could speak from the floor in 1939 to celebrate the annexation of Hatay to Turkey and advise the women of Hatay to remember to be “Turkish woman” and stay faithful to the cause of the Turkish woman. 15 That Hatay was a highly contested piece of land between Turkey and Syria, with a predominantly Arab population, had to be denied in the populist nationalist discourse. Women were doing their share in modernizing and defining the best interests of “other” women.

The Limits to Equality and Autonomy

While women who did their share in the Kemalist project of modernity could seek to be equal to men in the public realm, there were clear limits to women’s autonomy. (During the authoritative single–party era, many men, too, could not act autonomously in the public realm.) Women’s activism was circumscribed by the dictates of an autocratic Westernizing state. Zafer Toprak has brought to our attention two revealing cases of the way the modernizing state restrained women’s activism when it was considered dissonant with the interests of the state. In 1923, when women appealed to the authorities for permission to found a Republican Woman’s Party, they were refused. 16 It was argued that a woman’s party could detract attention away from the Republican People’s Party, soon to be founded. Similarly, in 1935, when the Turkish Woman’s Federation collaborated with feminists from around the world to host a Congress of Feminism in Turkey and issued a declaration against the rising Nazi threat, the modernizing elite was displeased. The federation was closed. 17 It was argued that the republic had given women all their rights and there was no more need for women to organize. Women had displayed increasing autonomy from state policies when they collaborated with feminists from around the world, especially when they criticized the Nazis while their government was carefully keeping a low profile on the international scene.

Although there were limitations to women’s autonomous public activism, the Kemalist discourse nevertheless provided legitimacy for women’s claim to equality with men in the public realm. Those who had access to that realm could benefit from this privileged equality. Yet the Kemalist understanding of equality was based on an assumption of sameness between men and women that could, in the public realm, be created artificially. This particular understanding of equality was transformed into a hierarchical relationship between men and women when their differences had to be acknowledged in the private domain. Durakbasa’s quote from Yeni Adam, a popular journal of the day, is revealing of the nature of equality espoused by the Kemalist modernizers.

In the land of the Turks, male–female distinction does not exist anymore. Distinctions between masculinity and femininity are not those that the nation pays attention to, labors over. They belong to the private existence of a single man; what is it to us? What we need are people, regardless of whether men or women, who uphold national values, national techniques. 18

The Kemalist project of modernity legitimized male–female equality as it denied male–female difference. Equality was conceived of as irreconcilable with difference. 19 Within this discourse, women’s equality to men in the public realm necessitated a denial of difference between men and women. To the extent that difference was acknowledged in the private realm, it precipitated hierarchy.

The cartoon in figure 7.3 is a telling illustration of how Atatürk himself, the champion of Westernization and women’s rights, was (or could be) a traditional patriarch in his private life. 20 Made by an Egyptian cartoonist and published in a Cairo weekly, Khayal al–Zill (Shadow Play) in 1925, the cartoon depicts Atatürk in traditional garb divorcing his Western–educated wife, Latife. He has shed his modernist mask, top hat, and evening dress—symbols of his Westernism—as he orders his wife out in a Shari’a–style divorce. In the private realm, Atatürk, the leader of women’s rights, is a traditional patriarch. Differences between men and women prevail, to the detriment of women.

|

| 7.3. A cartoon depicting Mustafa Kemal’s divorce as his taking off the Western mask. (Reproduced from Khayal al–Zill, August 1925.) |

Revisionist History: Feminist Assessment of the Project of Modernity

Until the 1980s, there was a consensus in society that Kemalist reforms had emancipated women and that this “fact” could not be contested. Not merely the educated professional women agreed; so did both educated and illiterate housewives who knew their daughters would benefit from opportunities the reforms provided. The consensus broke down when a younger generation of educated women professionals who called themselves feminists challenged the tradition. In search of new cultural identities, feminists criticized the project of modernity as it affected women. Their goal was not to seek equality with men in the public realm but to question the heritage which upheld that equality. They were ready to commit a sacrilege and deny being Atatürkists. 21

Recalling Nermin Abadan–Unat and Sirin Tekeli, who were introduced at the beginning of this essay, can help us identify the generational changes that have occurred in the polity and that are critical for putting the contemporary feminists into perspective. Both were educated elite intellectuals. Abadan–Unat had to sever her ties with tradition (which assigned homemaking roles to women) in order to get the education she did, and she had to cling to the opportunities the project of modernity provided to carve out her role in the academic world. Tekeli, born to Kemalist parents in Ankara, the heart of the new republic, could take her secular public education for granted. Tradition was set for her to move into the ranks of academia. She severed her ties when she rejected the role model of the successful career woman, which people like Abadan–Unat and her own mother provided for her, and resigned from her academic career. She created her own model for a new type of feminist. The Kemalist project of modernity had provided no special opportunity for her as it had for the earlier generation, and she could distance herself from its architects in a critical manner. In the unique context of the 1980s, when domestic and global factors charted the parameters of its political space, feminism emerged in Turkey. 22

Feminist criticism of the Kemalist project of modernity, specifically on questions of women, was radical because feminists altered the perspective from which women’s issues were addressed. They traced women’s problems to the way women were conceived of in the making of the new republic. For the founding fathers, the “woman question” was part of the populist project, which believed in acting “for the people against the people.” From this perspective, these men, and later the women who shared their legacy, could address the “woman question” in order to save the women of their country, not themselves.

Feminists, on the other hand, did not address the “woman question” per se. Instead, they addressed, or rather articulated, the problems they themselves experienced because they were women. It was a move from the personal, from what concerned them immediately, to what other women might share. In this approach there was no mission, no explicit goal to save others. In the feminist page of Somut, the weekly journal that was the first platform from which women who called themselves feminists raised a feminist voice, Stella Ovadia explained what they were doing:

We tried to say “I” or “we”; not “those” women, but “we women.” Not “woman questions” [kadin sorunlari], but questions of being women [kadinlik], becoming women [kadin olma], attempts to become subjects. To tell about ourselves and speak in our name. Finally to have a say. And write, learn to write, go beyond our fears. 23

This feminist perspective was radically different from the republican modernist one, which assumed that the best interest of society came prior to the best interest of the individual or any group of individuals and that the modernizing elite responsible for guarding the “best interest” also knew what it consisted of. In a private interview, another feminist described Kemalist women or Kemalist feminists as follows, when she explained the differences between the older and younger generations: “These women [the Kemalists] are content with what they are. They are “liberated” women; someone else liberated them for them. And they always want to liberate others. They are somewhere else. They were liberated by Atatürk. How dare a man raise his hand against them?”

This change of perspective that feminists brought precipitated further criticism of the republican project of modernity. When they articulated the problems they had because they were women, feminists discovered that within the republican project of modernity their private lives were smothered under the public expectations they had to live up to. Despite radical changes in the Civil Code, primordial male–female relations and the moralities that regulated gender relations could continue with little interference from the state. When private lives and interpersonal relationships were questioned, hierarchies and controls that had been ignored now surfaced. Sexual liberties and freedoms, once taboo, became articulated issues. Under the critical gaze of the older generation of Kemalist women, who claimed that society would not tolerate the sexual freedoms they demanded, 24 these radical feminists challenged the morality of their mothers and modernizing “fathers” in search of liberation beyond emancipation. 25 Sule Torun wrote of the fears feminists individually tried to conquer:

I cannot think about sexuality and write because it will be considered a shame [ayip olur]. I can not write beautiful, fluent prose; I should let good writers write. What I write might be too private and individualistic. Then they will accuse me of not being a communalistic person [toplumcu olmamak]. 26

The fears feminists had to conquer to be able to write as feminists reveal the parameters of the space created within the project of modernity for women to realize themselves. Repression of sexuality, faith in professionalism (or education), and respect for the community over the individual demarcate women’s space in the republican project of modernity.

One target of this introspection and protest was the republican legal framework. The laws, especially the Civil Code, which until the 1980s had been presented by the state (through the educational system or media) and accepted in public consciousness as progressive beyond time and place, were shown to be unegalitarian. In the Civil Code there were articles that designated the husband head of the family (art. 152/1) and representative of the marriage union (art. 154). The husband was allowed the privilege of choosing the place of residence (art. 152/2), and he was expected to provide for the family (art. 152/2). The wife was explicitly made to play a secondary role as helper to the husband for the happiness of the family. Beyond these articles, as feminists pointed out, the state was patriarchal, endorsing and legitimizing patriarchal institutions such as the family, the media, and the educational system.

From Individual Demands to Institution Building

Feminist demands for individual autonomy were creatively channeled toward building institutions. In a society where modernization meant state activism, women, for a change, were taking the initiative to bring about transformation. While they sought liberation individually, these women, who criticized the earlier generation for its “for the people against the people” populism, helped build institutions that allowed feminists to reach beyond their immediate circles. Feminist individualism manifested civic responsibility.

One of the two successful institutions established in Istanbul was the Women’s Library and Information Center, founded in 1990. The other was the Purple Roof Women’s Shelter Foundation, established the same year. Both institutions grew out of feminist activism in Turkey. Sirin Tekeli, in a speech delivered in April 1990 during the inauguration ceremony for the library, explained that the library was an outcome of this feminist awakening. Similarly, the brochure published by the Purple Roof Women’s Shelter Foundation explicitly stated that the idea of a women’s shelter was born together with the Campaign Against Domestic Violence. Perhaps ironically, the project proposal for the women’s library, which needed the support of the Istanbul municipality, referred to the egalitarian values of modernity to legitimize the need for the library. 27 On the other hand, to explain why the shelter was instituted, the foundation’s brochure appealed to norms of difference, claimed that one woman in four was beaten by her husband, and cited a survey by a public–opinion survey company, PIAR.

Feminist attempts at institution building thus channeled demands for autonomy into generating power from civil society. While these attempts may have been marginal in terms of the number of people they affected, they were significant in going beyond the tradition of “for the people against the people” in Turkey. Women were acting as women for women. These institutions were created by the women—not by the state for women. Perhaps ironically, to the extent that women reached out from the private to the political and from personal confrontation in their private lives to public institution building, which aimed to uphold and support other women, they were reaching out for universal values the way republican modernizers had. Although their starting points were very different, male–female equality was still an important goal.

Secularism

The most important tenet of Kemalist modernization that directly affected women had been secularism, including the secularization of the legal and educational system. The Civil Code and suffrage, critical for improving women’s status, were passed in opposition to religious groups and as a means of undermining them. In the contemporary scene, the new generation of feminists, as well as the Kemalist feminists, represent pillars of secularism in society.

Perhaps unique in an ultimately Muslim context, the new generation of radical feminists was not deeply threatened by the Islamist revival of the 1980s. Even though the feminists’ secular demands ultimately collided with the Islamist deference to a hierarchical God who, at best, circumscribed what women could and could not do, the two groups did not work against each other. In other Muslim contexts, such as Egypt and Pakistan, where Islamic practice and women’s activism had their own unique histories, there have been explicit clashes between feminists and Islamists. 28 In Egypt, Margot Badran has argued that Islamist and feminist agendas have been competing since the nineteenth century. 29 Similar competition has existed in other parts of the Muslim Middle East, even when nationalist demands, in places like Algiers or Palestine, have curbed women’s demands. 30 In the case of Egypt, the claim has been made that Islamist revival helped account for women’s activism in defense of their rights in the 1980s. 31

Against this background of the Muslim Middle East, the peculiar history of Turkish secularism and the way feminist activism contributed to that history can be better appreciated. In a context where competitions between Islam and secular ideology had long been won by secularists in the public realm, the new generation of feminists was not immediately threatened by the strong, visible Islamic revival. Their feminist activism began independent of Islamic activism. The parameters of this radical feminist activism were defined by Kemalism, the left, and the worldwide revival of feminism. Although they disagreed with women activists in the Islamist ranks and argued that theirs could not be considered “feminist” activism, some feminists, if not all, respected the fight Islamist women gave. 32

In an essay in which she first declared her atheism, Tekeli addressed women wearing the turban: “While I do not share your thoughts and beliefs and try to persuade other people that what you argue is not correct, I respect your turban and in fact condemn those who pressure you to take it off. What about you? Do you accept me as I am?” 33 For Tekeli, Islamist women were her equals, and she was proposing mutual recognition—the white flag, so to speak. In a reception given to celebrate the anniversary of the Women’s Library and Information Center, one could run into Islamist women with head scarves and men with Islamist beards.

In a polemical debate that took place in the journal Kaktüs between a group of Islamist women and Sedef Öztürk, a contributor to Kaktüs, Öztürk attempted to outline the points of convergence between feminist and Islamist women. She argued:

Perhaps the only common denominator they [feminists] could have with Islamist women was Islamist women’s claim that “being socialist, secular, or Muslim is not a guarantee of being kept under control as women.” Perhaps a second could be that as women who live in different class, national, ethnic, or religious groups and adopt different ideologies, we are all in fact in a struggle for ourselves against ourselves—at times challenging the limits of the other ideologies that shape our being, forcing the limits of Islam or socialism. 34

The feminist argument that underlined the problems women confronted because they were women would thus be the fulcrum of feminist solidarity, independent of other ideological links.

Unlike the younger generation, the Kemalist women perceived the Islamic upsurge more as a threat, and they did organize to counter it. The reaction of Kemalist women to the Islamists differed from that of the younger generation of feminists both in emotional intensity and in adversariness. The transformation of Kemalist women into Kemalist feminists took place as these women organized against the Islamist challenge in the late 1980s. They founded a group called the Association to Promote Contemporary Life (Çagdas Yasami Destekleme Dernegi) to fight the Islamists. 35 Aysel Eksi, its first president, explained their rationale:

For some time now, we have been confronted by a serious and surreptitious reactionary movement that hides behind the curtain of “freedom of woman to dress as she wishes” but in reality struggles to return our society to the darkness of the Middle Ages. We do not doubt that this reactionary movement, led by a handful of dogmatic, diehard Islamists who have roots outside [the country] and who deceive many of our well–meaning, innocent people, sees the destruction of the secular republic as its first goal and pursues the establishment of a shariat order. We came together with the awareness of this danger and the authority that Atatürk’s reforms have given us in order to protect the Atatürk reforms, the secular republic, and our rights, which are an inalienable part of these [reforms and the secular republic]. 36

The Kemalist women, as the quote reveals, see Islamist activism, as well as their relationship to the republic, in intensely emotional terms. While Islamists are depicted as reactionary, of the Middle Ages, and foreign, Kemalist women’s right to oppose them derives from the secular state. These women identify themselves and their power with the state. In an unmistakable sign of their distinctive discourse, one in which they—the educated elite—know the good of the other, they comment on “their” innocent people being deceived by reactionary Islamists.

Conclusion

Serif Mardin argues that “while the autonomy of the town was the core datum of Western civility, equity and justice in the lineaments of the State were the core values of Ottoman civilisation.” 37 The immediate heirs of the Ottomans, the Kemalists, in the context of their project of modernity, sought to make women equal to men. Proclamation of universal rights for men as well as women was both the goal of the modernist project and the means by which to actualize it. Implicitly, women were expected to act like men and be like men. In the 1980s, feminists asserted their differences. They sought autonomy for themselves through an autonomous civil society, “the core datum of Western civility.” In the 1980s, the republic was more “Western” and “modern” than it was in the 1920s.

Feminist activism in Turkey attests to the strength of the republican project of modernity in Turkey. Although feminists levy sharp charges against and distance themselves from Kemalists, it would be misleading to see Kemalist reformers and contemporary feminists in oppositional terms. Despite their revolt, feminists, in their search for autonomy, contribute to a liberal, secular, democratizing polity, which is what the Westernizing republic that the Kemalists founded stands for. Despite their criticisms, feminists ultimately believe in universal rights that go beyond local traditions and provincial moralities.

Endnotes

Note 1: Ahmet Taner Kislali, “Niçin Kemalist’im?” in Yillik: Nermin Abadan–Unat’a Armagan, Ankara: Ankara Üniveritesi Basimevi, 1991, ix–x. Back.

Note 2: Sirin Tekeli, “Tek Parti Döneminde Kadin Hareketi de Bastirildi,” in Levent Cinemre and Rusen Çakir, eds., Sol Kemalizme Bakiyor, Istanbul: Metis Yayinlari, 1991. Back.

Note 3: The board aimed to centralize and oversee higher education in Turkey. It had deleterious effects on universities and academicians, who resigned in the hundreds. Back.

Note 4: Tekeli, “Tek Parti Döneminde,” 93–107. Back.

Note 5: “Actors or pawns” is quoted from Deniz Kandiyoti, “Women and the Turkish State: Political Actors or Symbolic Pawns?” in Nira Yuval–Davis and Floya Anthias, eds., Woman–Nation–State, London: Macmillan, 1988. Back.

Note 6: Carlos Fuentes, The Buried Mirror, New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1992, 16–17. Back.

Note 7: The term “Kemalist feminist” points to the unique nature of this feminism. As MacKinnon, reacting to Marxist feminism, elaborates, feminism is “a politics authored by those it works in the name of,” and naming it after an individual demarcates a unique understanding of feminism. See Catharine MacKinnon, “Feminism, Marxism, Method, and the State: An Agenda for Theory,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Spring 1982, 516. Back.

Note 8: Tekeli, “Tek Parti Döneminde”; Yesim Arat, The Patriarchal Paradox: Women Politicians in Turkey, Fairleigh–Dickinson University Press, 1989; Kandiyoti, “Women and the Turkish State”; Ayse Durakbasa, “Cumhuriyet Döneminde Kemalist Kadin Kimliginin Olusumu,” Tarih ve Toplum, no. 51, March 1988; Nilüfer Göle, Modern Mahrem, Istanbul: Metis Yayinlari, 1991; Zehra Arat, “Turkish Women and the Republican Reconstruction of Tradition,” in Fatma Müge Göçek and Shiva Balaghi, eds., Reconstructing Gender in the Middle East: Power, Identity, and Tradition, New York: Columbia University Press, 1994; Ayse Kadioglu, “Birey Olarak Kadin,” Görüs, May 1993. Back.

Note 9: Kandiyoti, “Women and the Turkish State.” Back.

Note 10: Afetinan, Atatürk Hakkinda Hatiralar ve Belgeler, Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basimevi, 1959, 257. Back.

Note 11: Zehra Arat, “Turkish Women,” 3. Back.

Note 12: Yael Navaro, “‘Using the Mind’ at Home: The Rationalization of Housewifery in Early Republican Turkey (1928–1940),” honors thesis submitted to the Department of Sociology, Brandeis University, 1991. Back.

Note 13: By 1940, 35 girls institutes existed in 32 different cities, and 65 evening girls art schools in 59 towns. In the school year 1940–41, 16,500 women were enrolled in these schools. Back.

Note 14: Quoted in Durakbasa, “Cumhuriyet Döneminde,” 43. Back.

Note 15: Yesim Arat, “Türkiye’de Kadin Milletvekillerinin Degisen Siyasal Rolleri, 1934–1980,” Ekonomi ve idari Bilimler Dergisi, Bogaziçi University, vol. 1, no. 1, 1987, 50. Back.

Note 16: Zafer Toprak, “Cumhuriyet Halk Firkasindan Önce Kurulan Parti: Kadinlar Halk Firkasi,” Tarih ve Toplum, March 1988, 30–31. Back.

Note 17: Zafer Toprak, “1935 Istanbul Uluslararasi ‘Feminizm Kongresi’ ve Baris,” Düsün, March 1986, 24–29. Back.

Note 18: Quoted in Durakbasa, “Cumhuriyet Döneminde,” 43. Back.

Note 19: For an eloquent analysis of how equality and difference cannot exist in opposition to each other and how the concept of equality is contingent on an assumption of difference, see Joan Scott, “Deconstructing Equality versus Difference, or the Uses of Poststructuralist Theory for Feminism,” Feminist Studies, vol. 14, no. 1, 1988, 33–50. Back.

Note 20: I would like to thank Professor Günay Kut of Bogaziçi University, Department of Turkish Language and Literature, for helping me with the translation from the Arabic in this cartoon. Back.

Note 21: To underline the novelty of someone’s denying to be a follower of Atatürk, and as a reminder of Atatürk’s deification in Turkey before the 1980s, I quote Vamik Volkan and Norman Itzkowitz, The Immortal Atatürk: A Psycho–biography, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984, 345–46: “As a national leader, Atatürk became a necessary idealized object of his countrymen, one essential for the maintenance of Turkish pride.... [He] has continued to live as a symbol and a concept. His picture continues to be reverenced alongside the national flag and is displayed beside it on days of national celebration or remembrance. He is omnipresent. He is on postage stamps and money, both bills and coins. Statues of Atatürk are everywhere, and his words are chiseled on the stone facades of buildings. His photograph is found in government offices and in the corner grocery store. His name has been bestowed on boulevards, parks, stadiums, concert halls, bridges, and forests. When the Turks seized the northern sector of Cyprus in 1974, busts of Atatürk were brought ashore with the troops and erected in every liberated Turkish village. Mental and physical representations of Atatürk have fused with and are symbolic of the Turkish spirit, and thus he has indeed become immortal.” Back.

Note 22: Sirin Tekeli, “Women in the Changing Political Associations of the 1980s,” in Andrew Finkel and Nükhet Sirman, eds., Turkish State, Turkish Society, London: Routledge, 1990; Nükhet Sirman, “Feminism in Turkey: A Short History,” New Perspectives on Turkey, vol. 3, no. 1, 1989, 259–88; Yesim Arat, “1980’ler Türkiyesi’nde Kadin Hareketi: Liberal Kemalizmin Radikal Uzantisi,” Toplum ve Bilim, no. 53, Spring 1991, 7–20. Back.

Note 23: Stella Ovadia, “Bu Yazi Son Yazi mi Olacak,” Somut, 27 May 1983. Back.

Note 24: Necla Arat, Feminizmin ABC’si, Istanbul: Simavi Yayinlari 1991. Back.

Note 25: Deniz Kandiyoti, “Emancipated but Unliberated? Reflections on the Turkish Case,” Feminist Studies, vol. 13, no. 2, 1987, 317–38. Back.

Note 26: Sule Torun, “Genel Bir Degerlendirme,” Somut, 27 May 1983. Back.

Note 27: More precisely, the proposal responded to the question “Why the need for the women’s library?” as follows: “The modernity of a country is measured by its degree of male–female equality. This process is particularly important for our country. The attainment of this equality requires various endeavors. To reach this aim, institutions that nurture it and help reach it are necessary. In a broad spectrum, these range from a Ministry of Woman’s Rights to a Women’s Library” (Kadin Eserleri Kütüphanesi ve Bilgi Merkezi Vakfi Kurulus Taslagi, 3). Back.

Note 28: Nadia Hijab, Womanpower: The Arab Debate on Women at Work, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988, 30–35; Ayesha Jalal, “The Convenience of Subservience: Women and the State of Pakistan,” in Deniz Kandiyoti, ed., Women, Islam, and the State, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991, 77–114. Back.

Note 29: Margot Badran, “Competing Agenda: Feminists, Islam, and the State in 19th and 20th Century Egypt,” in Kandiyoti, ed., Women, Islam and the State, 201–36. Back.

Note 30: Hijab, Womanpower, 26–29; Rosemary Sayigh, “Palestinian Women and Politics in Lebanon,” in Judith E. Tucker, ed., Arab Women, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993. Back.

Note 31: Mervat Hatem, “Toward the Development of Post–Islamist and Post–Nationalist Feminist Discourses in the Middle East,” in Judith E. Tucker, ed., Arab Women, 31. Back.

Note 32: Gül, “Hem Mümine Hem Feminist,” Feminist, no. 4, 1988. Back.

Note 33: Sirin Tekeli, Kadinlar için, Istanbul: Alan Yayincilik, 1988, 381. Back.

Note 34: Sedef Öztürk, “Elestiriye Bir Yanit,” Kaktüs, no. 4, November 1988, 28–30 Back.

Note 35: The association opened its ranks to men and women but only women responded. There were about six hundred members of the association in the summer of 1993. Back.

Note 36: Aysel Eksi, “Neden Kurulduk,” Çagdas Yasami Destekleme Dernegi Bülten, no. 1, March–June 1989. Back.

Note 37: erif Mardin, “European Culture and the Development of Modern Turkey,” in Ahmet Evin and Geoffrey Denton, eds., Turkey and the European Community, Opladen, Germany: Leske and Budrich, 1990, 14. Back.