|

|

|

|

Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey

University of Washington Press

1997

6. The Quest for the Islamic Self within the Context of Modernity

Modernization theories have forced us to look for symmetrical and linear lines of development, sometimes to the exclusion of historical and geographical context. According to these theories, there are universally defined variables and causal sequences between variables (for instance, education and urbanization, economic development and democracy) that create modernization quite independently of time and space. Now, the epistemological pendulum has swung from causal reasoning and methodological positivism toward the question of agency and the analysis of specific, context-bound interpretations of modernity. This shift has had an undeniably liberating effect on the study of non-Western countries. Distancing oneself from universalistic approaches to modernization permits one to examine the subjective construction of meaning and cultural identity—the construction of specific articulations between the local fabric and modernity.

Yet as Anthony Giddens has pointed out, “a rethinking of the nature of modernity must go hand in hand with a reworking of basic premises of sociological analysis.” 1 As we move toward an understanding of new forms of hybridization between the particular and the universal, and between local and global realities, we traverse a terrain that has not been explored or explained in the language of the social sciences. This creates, at the outset, a problem of conceptualization. A common approach is to consider all sorts of puzzling hybrids and paradoxes as either parochial signs of a “pathology of backwardness” or simply as postmodern relativisms.

There are two ways in which the study of Islamic movements is related to this intellectual shift from universalistic conceptions to a particularistic analysis of modernization. 2 First, by excluding Islamic identity and culture, the totalizing nature of modernization reveals itself. The reassertion and reelaboration of an Islamic self via political empowerment implicitly addresses the impact of modernization, which has penetrated into the most intimate spheres of everyday life, from definitions of self to gender relations and ethical and aesthetic values. Second, the study of contemporary Islamic movements challenges the assumed binary opposition between tradition and modernity. In doing so, it focuses particular attention on the connections between faith and rationality, morality and modernity, individualism and community, and intimacy and transparency.

Thus, the reconstruction of Western modernity in a Muslim context can help us comprehend competing legitimacies and the Islamic perspective on modernity. Such a cross-reading will assist in integrating what otherwise might be considered the oppositional notions of “the East” and “the West,” or “Islam” and “modernity.” Instead, the emphasis will fall on the critical interaction between these concepts.

The Civilizing Project and the Turkish Self

Current scholarship explains Islamic movements by assigning priority either to sociopolitical factors or to some part of the religion itself that is presumed to be alien to a series of transformations such as reformism and secularism that occurred in the West. If the research follows the first course, it develops causal reasons—economic stagnation, political authoritarianism, rural exodus—to explain the rise of radical Islam. This type of approach describes the social environment within which oppositional movements are rooted, but it fails to address the reasons why Islam appeals so strongly to the need for cultural and political empowerment. Lines of research that focus on the essence of Islam as a religion, on the other hand, suppose an immutable quality in Islam and thereby take it out of its historical and political context. Scholarship of this sort simply expresses the politico-religious nature of Islamic movements as a summing up of the two different phenomena.

There is no denying that a sphere of tension exists that is sharpened by Islamic movements. This sphere is situated at the crossroads of religion and politics. The debate is defined by different conceptualizations and normative values assigned to such terms as self, gender relations, and modes of life. On the one hand, Muslims define themselves through religious belief, but on the other hand, it is radical politics that empowers and conveys this meaning. Through Alain Touraine’s framework of analysis, this sphere of tension can be approached. 3 Touraine sees social movements as struggles for control of cultural models, struggles that are not separate from class conflict. In his formulation, Islamic movements do not express solely a politico-religious opposition but also present a countercultural model of modernization.

To make this realm or sphere of conflict more explicit, one needs to explore the mode of modernization undertaken in Turkey and in the majority of Muslim countries. The study of contemporary Islamic movements, therefore, necessitates a reevaluation of the recent history of Turkish modernization. This period spans the second half of the nineteenth century, when modernization began under the tutelage of Ottoman elites, and most of the twentieth, with the formation and growth of the republican Kemalist elite. One can better understand the problematic relations between Islam and modernity if one takes into account the constructions of “Western modernity” at the local, cultural, and historical levels. Rather than studying relations between Islam and the West, where the West is taken to be an external and physical entity, it is more productive to focus on indigenous forms of modernity. This means examining how the Western ideal of modernity is reconstructed and internalized locally, and how the power relations between Islamic movements and modernist elites take shape.

Often, the transforming impact of Western modernity is studied at the level of state structures, political institutions, and the industrial economy. Its less tangible but more penetrating effects, however, are on the cultural level, in lifestyles, gender identities, and self-definition of identity. The modernization project takes a very different turn in a non-Western context, for it imposes a political will to “Westernize.” The terms “Westernization” and “Europeanization,” which were widely used by nineteenth- and twentieth-century reformers, overtly express the willing participation that underlies the borrowing of institutions, ideas, and manners from the West. The history of modernization in Turkey can be considered the most radical example of such a voluntary cultural shift. Kemalist reformers’ efforts went far beyond modernizing the state apparatus as the country changed from a multiethnic Ottoman empire to a secular republican nation-state; they also attempted to penetrate into the lifestyles, manners, behavior, and daily customs of the people. With the renewal of the Islamist movements during the 1980s, a historical return—a reconsideration of this “civilizing” shift—became crucial to understanding the emotional, personal, and symbolic levels that defined the conflicts and tensions between Islamists and modernists. 4

The Turkish mode of modernization is an unusual example of how indigenous ruling elites have imposed their notions of a Western cultural model, resulting in conversion almost on a civilizational scale. By building up a strong tradition of ideological positivism, Turkish modernist elites have aimed toward secularization, rationalization, and nation building. The premises of positivist ideology are crucial in the realization of this project. 5 First, positivism holds universalistic claims for the Western model. By not considering Western modernity an outcome of a particular Christian religious culture, positivism focuses on scientific rationality. It represents this model of change as universal, rational, and applicable everywhere and at any time. It is Comte’s ultimate positivist stage, which all societies will one day achieve.

Second, the French positivists’ motto, “order and progress” (instead of the market anarchy of the British liberals), gives Turkish nationalists powerful encouragement in their attempts at social control. For the ruling Kemalist elites, the unity of society achieved through “progress” of a Western sort is the ultimate goal. Thus, throughout republican history, all kinds of differentiation—ethnic, ideological, religious, and economic—have been viewed not as natural components of a pluralistic democracy but as sources of instability and as threats to unity and progress. Such a perspective permits Turkish modernist elites to legislate and legitimate their essentially antiliberal platform.

The all-encompassing nature of the Turkish “civilizing” project can better be apprehended in reference to Norbert Elias’s work. 6 Although the concept of civilization refers to a wide variety of factors, from technology to manners and religious ideas and customs, it actually expresses, as Elias points out, the “self-consciousness” and “superiority” of the West. Technology, rules of conduct, worldview, and everything else that makes the West distinctive and sets it apart from more “primitive” societies impart to Western civilization a superiority that lends a presumption of universality to its cultural model.

Attempts at modernization in Muslim countries become a matter of “civilization” when they are defined essentially by Western experience and culture. Western history has reached a number of peaks, from the Renaissance through the Enlightenment and into the industrial era. It continues to maintain its dominance in the information age. In doing so, it has created its own terrain for innovation and has become the reference mark for modernity. Non-Western experiences no longer make history and are defined as residual, granted an identity only in their difference from the West, namely, as non-Western. As Daryush Shayegan notes, societies on the periphery of Western civilization are excluded from the sphere of history and knowledge, for they can no longer participate in the “carnival of change” and therefore have entered into “cultural schizophrenia.” 7 These societies have a “weak historicity,” that is, a feeble capacity to innovate or create in their own environment. As a result, their history becomes a continuous effort to imitate, to modernize, and to position themselves in relation to presumed Western superiority. In this cycle, encounters between East and West result not in reciprocal exchanges but in the decline of the weaker, typified in the Middle East by the decline of the Islamic identity.

The term “civilization,” then, does not refer in a historically relative way to each culture—French, Islamic, Arabic, African—but instead designates the historical superiority of the West as the producer of modernity. The concept of civilization refers to something that is constantly in motion, moving forward, encompassing the idea of progress. Therefore, it not only refers to a given state of development but also carries with it an ideal to be attained. Contrary to the German notion of kultur, which stresses national differences, civilization has a universal claim—it plays down national differences and emphasizes what is common among peoples. 8 It expresses the self-image of the European upper classes, who see themselves as the “standard-bearers of expanding civilization,” and it is the antithesis of barbarism. 9 As Turkish modernists have repeatedly stated, the main objective of reforms is to “reach the level of contemporary civilization” (muassir medeniyet seviyesine erismek), that is, of Western civilization. An irony of history is that the Turks, who for centuries symbolized to Europeans the barbarian, Muslim other, are now trying to enter the arena of the “civilized” in part by inventing their own “barbarians” in the form of, first, the Muslims, and second, the Kurds.

The Kemalist Woman and Western Civility

The concept of civilization is by no means value-free or neutral. It is, instead, a concept that refers to power relations between those who appropriate civilized manners and all others, who are, by default, barbarians. Consequently, in the Turkish process of modernization, the distinction between what is considered civilized and what is considered uncivilized comes under scrutiny. Everything that is alafranka (the European way) is deemed proper and valuable; anything alaturka (the Turkish way) acquires a negative connotation and is somehow inferior. It is interesting to note that Turks now use the foreign word alaturka to describe their own habits. 10 Wearing neckties, eating with forks, shaving, attending the theater, shaking hands, dancing and wearing hats in public, and writing from left to right are some of the behaviors that characterize a progressive and civilized person.

This individual ideal is transmitted most vividly through the image of the emancipated—that is, Westernized–woman. Every revolution defines an ideal man, but for the Kemalist revolution, it is the image of an ideal woman that has become the symbol of the reforms. In the Turkish case, the project of modernization equates the nation’s progress with the emancipation of women. Even more than the strengthening of judicial and human rights, it is the status of women as public citizens and women’s rights in general that are the backbone of the Kemalist reforms. 11 The participation of women in the public sphere necessitates, in the opinion of the modernists, taking off the veil, establishing compensatory coeducation, granting women’s suffrage, and the social mixing of men and women.

Kemalist feminism, with its sights set on public visibility and social mixing of the sexes, is creating a radical reappraisal of what are considered the private and public spheres. At the same time, its actions are prompting a reevaluation of Islamic morality, which is based on control of female sexuality and separation of the sexes. The deepest intellectual and emotional chasms between the modern West and Islam exist at the level of gender relations and definitions of the private and the public. Women appear as markers of the frontiers both between the intimate and the public spheres and between the two civilizations. As a result, Kemalist women who participate in public life are liberated from the religious or cultural constraints of the intimate sphere. But they also face a radical choice: culturally, they must be either Western or Muslim.

The Turkish experience is exceptional among its Muslim counterparts in its “epistemological break,” its radical discontinuity between traditional self-definitions and Western constructs. The majority of the population can easily create hybrid forms in their daily practice of religion, traditional conservatism, and modern aspirations. But the modernist elites, with their value-references tied to binary oppositions, have clearly sided with the “civilized,” the “emancipated,” and the “modern.” This generates a cognitive dissonance between the value system of the elites and that of the rest of the population, which results in contesting legitimacies. 12 Furthermore, the Kemalists formulate their discourse from the center of power backed by the state, whereas the Islamists formulate theirs through opposition.

“Islam Is Beautiful”: A Quest for Legitimacy

The upheavals in lifestyles and in aesthetic and ethical values that occur when an Islamic culture seeks modernization are not independent of social power relations. Western taste as a social marker of “distinction” establishes new social divisions, creates new social status groups (in the Weberian sense), and thus changes the terms of social stratification. Thus, there emerges an arena of struggle, or “habitus,” as Bourdieu calls it, that exists beyond will and language and encompasses habits of eating, body language, taste, and so forth. 13

Contemporary Islamic radicalism reveals this struggle in an exaggerated form. It is critical of the notion that what is “civilized” is “Westernized.” The politicizing of Islam empowers and encourages Muslims to return to the historical scene with their own ethics and aesthetics. The politics of the body conveys a distinct sense of self and society in which control (and self-control) of sexuality becomes the central issue. 14 Thus, the veiling of women, the most visible symbol of Islamization, becomes the semiology of Muslim identity. But men’s beards, and chastity, and prohibitions against promiscuity, homosexuality, alcohol consumption, and so forth, also define a new consciousness of an Islamic self and an Islamic way of life quite distinct from the “common,” “traditional” Muslim identity. What is new here is how, with regard to modernity, Islam is reconstructed and positioned in a new, conflicting, and more confident role.

Traditionally, a woman’s status in society parallels the “natural” life cycle as she passes from young girl to married woman and then grandmother. She is denied both individual choice and political power. Women participating in radical Islamic movements not only gain some control over their lives, as they break from traditional roles and develop personal strategies for education and career, but also politicize the entire Islamic way of life.

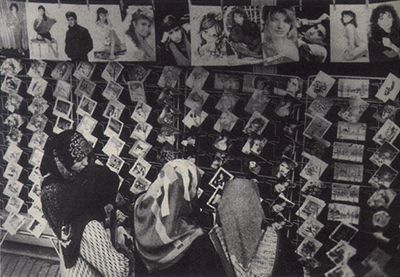

Islamist female attire, for instance, includes the convention of veiling. But this sort of veiling has little in common with traditional ways of covering the body. It has even less to do with the image of a Muslim woman as docile, devoted to her family and to her traditional roles of mother and spouse (see fig. 6.1). In Turkey, the word türban is used to denote the new Islamist head covering, whereas basörtüsü (“head scarf”) refers to the older, more traditional style. In Iran, the chador is worn both by militant and educated Islamist professional women and by the masses of traditional women. But it is interpreted differently by each group. Islamist professional women emphasize the Islamic way of dressing. They wear the chador as a powerful statement; it often covers an Islamic dress that completely envelops the body, preventing any possibility that the feminine form might be revealed while the wearer is active. Traditional Muslim women are more practical and pragmatic about wearing a chador. It is simply a covering that can be thrown quickly over their indoor attire and held closed with one hand as they go about their daily chores in the streets.

|

| 6.1. Istanbul in the 1990s: young girls in head scarves looking at posters of Turkish popular music and film stars. (Photograph by Haluk Özözlü; reproduced from Istanbul, 7 October 1993.) |

Such different uses of coverings exemplify the blurring of borders between tradition and modernity. Islamist ways are radically reappropriated by those who have already acquired and are making use of much of modernity. They have been educated, they move about in public urban spaces, and they have influence in the political realm. Thus, Islamism is an expression of the intensifying voice of Muslim identity as that identity, in its search for legitimacy, is radicalized and politicized in the modern world.

In their relationship with enlightened modernity, the Islamic movements exhibit the same critical sensitivity as other contemporary Western social movements. They are not substantially different from black, feminist, environmental, or ethnic movements. 15 All of these movements vividly demonstrate the force that can arise out of repression. A common feature of the postmodern condition is the tension that exists between identity politics, particularism, and localism, on one side, and the uniformity of abstract universalism, on the other. Like feminism, which questions universalistic and emancipatory claims and asserts that women are different and cannot be subsumed under the category “human being” (which is identified with men), Islamism takes issue with the universalism of “civilization” (identified with the West), which does not recognize Islamic differences. Women sharpen their identity by calling themselves feminists; Muslims do the same by labeling themselves Islamists. The sentiments of protest against and rejection of the dominant culture of white, Western men are captured in the phrase “black is beautiful.” It is a motto that resonates with pride in that which is different, and it is a source of empowerment in the politics of identity. The motto “Islam is beautiful” is gaining the same sort of potency in Islamic contexts.

Body Politics: The Islamization of Lifestyle

The quest to maintain an identity separate from that of the dominant West—the quest for an “authentic” Islamic way of being—engenders a hypercritical awareness both of traditional, common ways of practicing Islam and of the contemporary forms of Western modernity that homogenize lifestyles through globalization. Islamist intellectuals call for a return to the origins of the faith and for an investigation of Islam’s golden age (asr-i saadet), the era of the Prophet, in the hope that there they will find strategies for coping with “westoxication” and for correcting traditional misinterpretations. 16 The radicalism of the Islamic movements stems from this search for the original, fundamental interpretations of Islam. A new definition of the Islamic self is rooted in a religiosity repressed by secularism and is sought in the reinvention of traditions destroyed by modernization.

Body politics is crucial in revealing the new consciousness of the Islamic self as it resists secularism. In the view of Islamist women, veiling has nothing to do with subservience to men or to any other kind of human power. Rather, it expresses the recognition of God’s sovereignty over humans and submission to that sovereignty. Readopting the Islamic covering for women, particularly the head scarf, expresses a strong self-assertiveness and constitutes almost a reconversion to Islam. 17 Islamic women consider their religiosity something “natural,” “always there,” just waiting to be rediscovered. The veil makes Islamization real by an individual act, but it does not admit individualism. It expresses the critical assertiveness of Islamic women with respect to the modern individual who is emancipated from spiritual references and thus secularized.

Secularization and equality, the most significant experiences of Western modernity, are interpreted in the Muslim context as an assault on the most private realms and on social relations. The principle of equality confers legitimacy on a continuous societal effort to overcome social differences that the Muslim accepts as natural and insurmountable. Equality among citizens, races, nations, workers, and sexes defines the historical and progressive itinerary of Western societies. As more realms of social life are delivered from spiritual and natural definitions, the process of secularization deepens. This synergy between secularism and equality is considered the ultimate product of the modern Western individual.

The semiology of body care as manifested by the secularized person and the religious person indicates different conceptions of the body and the self. For the modern individual, the body is being liberated progressively from the hold of natural and transcendental definitions. It enters into the cycle of secularization, eventually penetrating the realm where human rationality exercises its will to master and tame the body through science and knowledge. Genetic engineering and manipulation of reproduction are two examples of such highly scientific interventions. But phobias over cholesterol, taboos on smoking, and an obsession with fitness are more mundane examples of how the notion of health, inspired by scientific rather than by erotic desires, now determines lifestyles. Body sculpting, fitness, and energy are the ideals of the modern individual, who is witnessing the leveling of differences between the sexes and the age groups and the replacement of life cycles with lifestyles. 18

Through Islamization, specifically the application of Islam to everyday life, differences between the sexes are scrupulously maintained and placed in a clear hierarchy. Any blurring of the border between feminine and masculine roles is considered a transgression, especially the physical masculinization of the female. In this context, veiling becomes a trait of femininity, of feminine modesty and virtue. Furthermore, in the Islamic context, the body has a different semantic: it mediates devotion to religious sacraments, and through ablution, fasting, and praying, it is purified. In addition to the physical body, the spiritual being (nefs) is mastered and cleansed through submission to divine will.

But even this comparison is not purely a matter of difference between secular and religious conceptions of self, a difference that exists in almost all religions. Instead, it is a civilizational matter. The notion of body and self explains the almost compulsory resistance of contemporary Islamists to secularism and equality. The Islamic self, which is reconstructed in conflicting power relations with the premises of the modern individual, makes itself different from the latter by seeking its own roots and foundation. 19

Modern societies are driven to “confess,” to “tell the truth about sexuality,” as Michel Foucault would put it. 20 According to Foucault, the emergence of modernity can be understood only by taking into account this urge (stemming from earlier religious practices) to confess the most intimate experiences, desires, illnesses, uneasinesses, and guilts in public in the presence of an authority who can judge, punish, forgive, or console. This explains how everything that is difficult to say, that is forbidden and rooted in the personal, private sphere, is confessed, made public and political. Popular talk shows in the United States, which are filled with discussions of sexual harassment, abuse, abortion, rape, and crime, serve as venues in which confessions are made and “truth” sought.

In opposition to the modern West, where the basic presupposition is that absolute truth is a matter not of the collective but of the individual conscience, in Islam this urge is met by submitting oneself to God and letting the community (cemaat) serve as one’s guide through life. 21 Veiling reminds us that there is a forbidden, intimate sphere that must be confined to the private and never expressed in public. Therefore, by refusing to assimilate Western modernity and by rediscovering religion and a memory repressed by rationalism and universalism, the Islamic subject elaborates and redefines herself. Islam as a lifestyle provides a new anchor for the self and thereby creates an “imagined political community” that reinforces social ties among people who do not know each other but who share the same dreams and spiritual attachments. 22 Islamism is more than a political ideology, for it creates a community forged in the crucible of the sacred. 23

The Quest for Islamic Identity

One of the most important traits of the Islamic movement that differentiates it from other contemporary social movements is that it retains a holistic strategy of change and the vision of an Islamic utopia. Contemporary Western social movements have become disenchanted with the totalitarian nature of utopian thinking and have been inclined toward a self-limitation in their projects, which admits more pluralism.

The “rise of the oppressed” can be emancipatory only if it is not itself repressive. The quest for “difference,” “authenticity,” and “morality,” necessary as an early elaboration of identity, has its own limitations. It can lead to essentialist definitions and exclusionary stands—Who decides what is Islamic? Who is a real Muslim?—that undermine and subvert the “imagined community” into an oppressive kind of communal authoritarianism. Such totalitarianism is made especially combustible by the search for an all-embracing Islamic identity liberated from the corrupting and domineering effects of Western modernity. As with any utopian philosophy, here, too, there is no place for conflict, for pluralism, or for interaction. The more the relationship between the “pure” self and the “total” community is reinforced, the more Islamic politics becomes that of authoritarian intervention in personal choices.

The relationship between Islamic identity and Western modernity is a crucial one. At the level of discourse, modernity is constantly criticized, but at the levels of individual behavior, political competition, and social practice, the interaction between the two grows deeper and more complex daily. Islamic intellectuals, who are keenly aware of this phenomenon, express their disappointment and address their critique toward the forms of modernity appropriated by Islamists themselves. Islamic pop music and fashion shows are only a few of the indicators of the degree to which modernity has infiltrated the Islamic community. One of the milestones in the quest for Islamic identity within the context of modernity will be the way in which the Welfare Party (Refah Partisi) moves from the periphery to the center of power as it attempts to reconcile its philosophy with the aspirations of the urban lower classes, who are more interested in embracing modernity than in rejecting it.

Endnotes

Note 1: Anthony Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1991. Back.

Note 2: I use the terms “Islamic movements” and “radical Islamism” interchangeably to designate contemporary Islamic movements as a collective action whose ideology was shaped at the end of the 1970s by Islamist thinkers all over the Muslim world (e.g., Maudoodi, Sayyid Qutb, Ali Shariati, and Ali Bulaç) and by the Iranian revolution. The term “radicalism” is used in the sense that there is a return to the origins and foundations of Islam in order to realize a systemic change, to create an Islamic society, and to critique Western modernity. Islamic and Islamism are not differentiated, although the latter refers to the project of Islamization of society through political and social empowerment, whereas the former simply denotes Muslim culture and religion in general. Back.

Note 3: Alain Touraine, The Voice and the Eye: An Analysis of Social Movement, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981. Back.

Note 4: Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1984. Back.

Note 5: Nilüfer Göle, Mühendisler ve Ideoloji (Engineers and Ideology), Istanbul: Iletisim, 1986. Back.

Note 6: Norbert Elias, The History of Manners: The Civilizing Process, vol. 1, New York: Pantheon Books, 1978, 3. Back.

Note 7: Daryush Shayegan, Le regard mutilé, Paris: Albin Michel, 1989. Back.

Note 8: Elias, The History of Manners, 5. Back.

Note 9: Elias, The History of Manners, 50. Back.

Note 10: The word alaturka is still used colloquially by the Turkish elites with a negative connotation, although in recent years there has been an increased appreciation, or perhaps a nostalgia, for things Ottoman and Turkish. Back.

Note 11: This explains why today in Turkey the violation of women’s rights and the trampling of secularism upsets the elites even more than does the abuse of human rights or the reneging on principles of democracy. Back.

Note 12: In terms of historical classification and political experience, the legacy of the Democrat Party, which was at the forefront of the transition to political pluralism in Turkey in 1946, is of crucial importance. The Democrat Party, considered too liberal on religious and economic issues, gave voice to those segments of society that were independent of the bureaucratic, Kemalist state. It was a mediating influence and acted as a buffer between the state and society, a role that was filled nowhere else in the Muslim countries of the region. It may even be asserted that it is the Democrat Party legacy that represents Turkish “specificity,” rather than radical secularism, which has been imitated to a certain extent in the majority of Muslim countries. In this essay I have omitted a discussion of the Democrat Party’s legacy, since I believe it created a political representation of Muslim identity rather than a new intellectual legacy. In terms of initiating new paradigms of legitimacy, the events of 1923 and 1983 are by far the most important. Back.

Note 13: Bourdieu, Distinction. Back.

Note 14: Nilüfer Göle, Musulmanes et Modernes, Paris: Decourvert, 1993 (English edition Forbidden Modern, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997). Back.

Note 15: Craig Calhoun, ed., Social Theory and the Politics of Identity, New York: Blackwell, 1994. Back.

Note 16: The term gharbzadegi (“westoxication”), first used by the Iranian thinker Jalal Ali Ahmad, became popular among a whole generation of Iranian youths in the 1970s. Back.

Note 17: “Veiling,” “covering,” and “head scarf” are used interchangeably to designate the Islamic principle of hijab, that is, the necessity for women to cover their hair, shoulders, and the form of their body in order to preserve their virtue and not be a source of disorder (fitne). Contemporary Islamic attire is generally a head scarf that completely covers the hair and shoulders. The rest of the body is covered with a long gown that conceals the feminine form. Back.

Note 18: Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity, 80–81. Back.

Note 19: In this respect, although the word “fundamentalism” is widely criticized and frequently rejected, it more accurately describes the situation than does “traditionalism,” which supposes a continuity in time and in evolution. Back.

Note 20: Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, vol. 1, translated by Robert Hurley, New York: Vintage Books, 1990, 61. Back.

Note 21: C. A. O. van Nieuwenhuijze, The Lifestyles of Islam, Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1985, 144. Back.

Note 22: Here I am following Benedict Anderson’s analysis of nationalism and applying it to Islamism. See his Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London: Verso, 1983. Back.

Note 23: The French sociologist Emile Durkheim (1858–1917) pointed out almost a century ago the distinct realms of the sacred and the profane, both of which are essential in the establishment and production of social bonds. Back.