CIAO DATE: 06/06

Fall 2005 (Volume 4, Number 3)

RECENT LOCAL DEVELOPMENT MODELS IN TURKEY

This paper analyzes the changes in the spatial distribution of industry in Turkey following the 1980s, focusing on regional development policies. Using their local endogenous resources, certain provinces, also called ‘new industrial districts', made important leaps in the past couple of decades, while certain regions fell further behind. This paper aims to explain the success stories and extract lessons for progress in overcoming the vast regional disparities that remain.

Metin Özaslan*

In recent years, Turkey has become a notable country as a result of her economic and industrial development performance, solid financial system, strong links with the outside world and initiatives for joining the European Union. As an emerging market, many questions have also been raised about her economic and industrial development patterns. The aim of this article is to focus on the spatial shifts of industry on national geography and more specifically the new industrial districts as the vehicles of industrial growth and inter-regional balance in Turkey. The focus will be on the emergence of new industrial spaces and their promising development models, which are based on SME (small and medium size enterprises) networks, local entrepreneurship and bottom-up local economic development.

After 1980, the starting date of Turkey's export substitution model or outward oriented development strategy, considerable changes have been seen in the spatial distribution of industry as was evident in other countries. One of the most significant consequences of this process on the economic geography has been the emergence of new industrial districts.

Until 1980, Turkey focused on its domestic market on the basis of import substitution strategy, involving massive state investment in heavy industry and a policy of trade protectionism. The country also had a fixed exchange rate and because of that the national currency was overvalued. This inward oriented development strategy began to fail in 1976 as pressure increased on the lira, leading to an exchange rate crisis in 1977 that culminated in a political crisis in 1980 and a military coup. Therefore, the economic and social crisis, which worsened at the end of the 1970s, was to be remedied by the comprehensive stability and structural adaptation (restructuring) policies, declared on 24 January 1980. These measures not only constituted a turning point for the resolution of the existing crisis, but also for the role of the state in industrialization process and in the economy. The basic change in Turkey's economic policy was the transition from protectionism, to policies, which were dominated by market powers. The market economy system was based on private sector in which the price mechanism dominated. The distribution of resources and the investments and interventions of the state were reduced to a minimum. Opening the economy to international competition and liberalization became a powerful instrument, preparing the basis for structural change in the Turkish economy and has forced both the public and the private sector out of their previous molds.

As a result of these policies, significant improvements have been achieved in macro-economic indicators and in particular import and export values. The most important development has been realized in the exports of the manufacturing industry. The Turkish economy experienced a trend of relatively high growth from 1980 to 1994. With the exception of economic crises in 1994, 1999 and 2001, industry has undergone steady growth. Since 2001, industry has again experienced steady growth. Examining the period between 1980-2005, it can be seen that there was a direct relationship between the rate of industrial development and GDP. When the industry increases its share in GDP, the greatest contribution to this has come from manufacturing.[1] Export substitution policies have provided a suitable environment for the SMEs, with high capacity of adaptation and small and medium-sized cities (SMCs) with a high capacity of organization, to enter the process of economic development.[2]

During this period, SMEs started to gain importance in the economic structure of the country. One of the main reasons for this is the appearance of vertical disintegration tendencies in large companies as examined by some scholars in many countries in the world.[3] As a result, sub-contracting and inter-firm relations have become more common. The lower level of wages in SMEs has directed the large companies to contract out their productions. Another reason is the structure of Turkey, which is traditionally dominated by artisans and small enterprises in the production and service sectors, as the core of the economy.[4] SMEs, employing 1-250 employees, constitute 98.8 percent of all enterprises in Turkey. The SMEs' creation of employment with low levels of capital, have further increased their importance in the Turkish economy. SMEs have played an important role in terms of growth, employment, industrialization and employment after the 1980s. Furthermore, they have been less affected by the crises due to their flexible structures and have proven their ability to compete with large-scale firms.

Another development in the Turkish economy is increasing importance of the small and medium sized cities' (SMCs) specialization in particular sectors. These kinds of cities possess small society structures and intensive social bonds, making the flexibilities, required by flexible specialization type production organizations easier. Therefore, they possess several advantages for industrial organization, based on flexible specialization in the era of globalization. Within this framework, the emergence of SMCs, such as Denizli, Gaziantep, Kayseri, Çorum and Kahramanmaras, as important industrial spaces in the dominance of the globalizing market and the competition conditions, form an important aspect of the change experienced in the post-1980 era.

Regional Disparities and Development Policies

The public sector has played significant roles in the formation of development in Turkey and priority has been given to industrial development at the national level, on the other hand regional development has been neglected until 1960s. This has caused the agglomeration of industry and services in a few cities in the western part of the country. After the 1960s, with the introduction of planned development era regional development became a priority.[5] One reason for this is the over-concentration of the industry and capital at a few centers and the increase in regional disparities. In this era, industry has been located randomly in city centers and negative examples of industrial agglomerations have been seen in Haliç (Istanbul) and in Bornova (Izmir). Along with the increase in industrial investments in certain regions, modernization in agriculture and the developments in transportation and communication infrastructures have accelerated the process of migration from underdeveloped regions to developed ones. With migration, not only the labor force, but also rural and territorial capital has flowed towards the developed regions. Migration has further increased the development disparities among the regions. Two negative consequences of this development experience are: the emergence of urbanization, infrastructure, social and environmental problems in the urban areas of industrial concentration and the deepening of problems in underdeveloped regions. As a result of the massive migration, population, production factors and growth have concentrated in urban areas especially in the western part of the country, generating the twin issues of urban growth and less developed regions. Economic policies supporting agglomeration in the process of development have lost their ability to promote growth, due to decreasing efficiency in the developed cities and the increasing poverty in the underdeveloped regions. Thus, decentralization of development has become both possible and desired.

In the planned era, regional development and the industrial decentralization policies have been implemented to mobilize the local private capital and to facilitate its investments in their region of origin. The most significant regional development policies are integrated regional development plans (IRDPs)[6], Priority Development Areas (PDAs) and investment incentives policies,[7] Organized Industrial Estates (OIEs) and Small Industry Sites (SISs).[8] Five-year development plans (FYDPs) gave priority to the principle of reducing the disparities between the regions. However, the policies implemented in the five-year development plans have followed a fluctuating path and the process of industrial concentration in the western areas has continued. The main reason for this is the failure to provide the sufficient physical and social infrastructure investments, which constitute the minimum conditions for the survival of industry in the underdeveloped areas because of Turkey's limited resources allocated for regional development, large geographical size and the dispersed settlement structure.

Considering these kinds of restrictions, both the theoreticians and practitioners have begun to focus on the “growth poles” model both for the effective usage of the national resources and to provision of a balanced regional development. With the application of this model, the concentration of the industry in the selected urban centers and high potential of growth, it is thought that the scale and the external economies, derived from agglomeration economies, would be provided. As of 1982, 16 regional centers have been selected.[9]

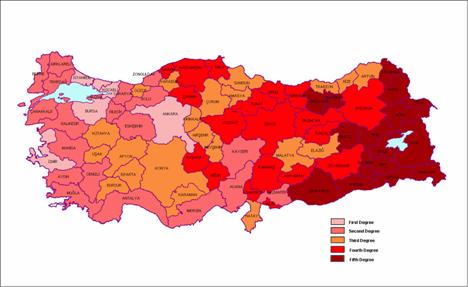

Despite all these efforts, neither Perroux-type growth poles model nor integrated regional development plans (IRDPs) with the exception of South-eastern Anatolia Regional Development Plan (GAP) could be implemented effectively in Turkey. Although many IRDPs have been prepared for various regions at different times, all of these, with the exception of the GAP, have not had an opportunity for comprehensive implementation. Moreover the GAP could not provide the desired effect due to problems in the organizational structure and failure in allocating necessary financial resources.[10] Although other policies, such as PDAs and OIEs have made significant contributions in the mobilization of the local potentials in some areas, they have fallen short in removing regional inequalities across the country. During this process, the inter-regional disparities within the country remained. Although the Turkish economy made considerable progress in terms of structural transformation and integration into the international markets, regional disparities still pose a serious problem in the 21st century. The long-term economic growth performance achieved by Turkey has not created the desired effect in terms of removing the regional inequalities. The public investments, the incentive measures oriented to the underdeveloped regions and various regional development policies has had a limited effect on balancing regional inequalities. During this time, bilateral polarization between the developed metropolitan cities and the underdeveloped regions has become more apparent.[11] Graph 1 and Map 1, prepared in accordance with the social and economic development index (SEDI), at the regional and provincial levels, show that there are significant development disparities between regions in Turkey.

Graph 1: Regional Disparities in Turkey, in Terms of SEDI

Source: Dincer and Özaslan, 2004

Map 1: Provincial Development Hierarchies in Turkey, in Terms of SEDI

Source: Dincer and Özaslan, 2004

The SEDI index reveals that the less developed regions have lower rates, in terms of GDP per capita, schooling rate, literacy rate, electricity consumption rate, added value of manufacturing industry, asphalted road rates, bank deposits and bank credits. At the same time, the regions are well above Turkey averages in respect of indicators like; fertility rate, infant mortality and population per doctor. A common characteristic of less developed regions is the predominance of agricultural activities. However, agricultural productivity is low and the hidden unemployment rate is high in agricultural sector. As a result of these unfavorable conditions, there has been a mass migration, including capital and young labor force, from these regions to developed regions, which in turn feeds the vicious circle of underdevelopment. Without external intervention by effective policies, it seems difficult for these regions to get out of this vicious circle. At present, the inequalities among the regions remain and constitute a tangle of problems, which also affect the social and political structures of the country. The most significant reasons for regional inequalities seem to be the failure to establish an effective administration and planning structure, providing an impetus to bottom-up development at the provincial and district levels in the rural areas. Provincial and district administrations have displayed inadequacies, with respect to the organizational and functional perspectives in an environment of changing economic, social and political conditions and the emerging needs. The failure of top-down public policies has directed the attention to the bottom-up local development approaches, which emphasize the dynamism of the local actors, local entrepreneurship and the development of local endogenous resources, as well as development and planning initiatives at the provincial level. Therefore, statutory developments such as “development agencies” and administrative reforms have arisen in the last several years aiming at bottom-up development.[12]

In short, throughout the planning period of Turkey, there had been continuous attempts to promote regional development. However, due to the size of the country as well as the rapid structural changes and economic growth, the necessity of accelerating the regional development process still remains to be achieved. In this context, the need for improving regional competitiveness of the less developed regions by stimulating their internal potential, which will approximate the development indicators of these regions to those of the national average is obvious. This is aimed to constitute a balanced regional pattern throughout the country.

National resources and external means such as European Union supports shall perform a significant function in achieving this aim.[13] In addition, while allocating resources, one of the main objectives of the State Planning Organization (SPO) is to improve regional competitiveness and stimulate internal potential of the regions for achieving a sustainable regional development pattern. Within this context the development models of the new industrial districts seem to be significant for deriving policies in order to strengthen regional competitiveness and pursue a bottom-up development path on the basis of local endogenous resources and potentials.

The Emergence of New Industrial Districts

In the periods before and after 1980, industry was agglomerated in major metropolitan centers. These industrial centers are led by Istanbul, Izmir and Adana, which are located in the western part of the country and which are dominated by the private sector investments. The industrial centers, mainly developed on the basis of the state owned enterprises in the import substitution era are the capital city of Ankara, Zonguldak in the mining sector, Karabük in iron-steel, Kirikkale in machinery-chemical industry and oil refining and Eskisehir in railroad and railroad car production. The over-concentration of the industry in the western regions has worsened the regional disparities between the western and the eastern parts of the country.

The most attractive spatial development tendency experienced in Turkey in the outward oriented development strategy period has been the emergence of new industrial districts. Since the 1980's some urban centers, defined as the new industrial districts (NIDs) have begun to industrialize rapidly and become prominent. Despite the failure of the top-down regional development policies of the state, the industrial districts are considered important for the spread of industry and development all over the country. The simultaneous and bottom-up development model of the industrial districts has replaced former approaches like the Perrouxian top-down growth poles creation policy.

While the cities based on the public entrepreneurship and industrial investments declined, the new industrial districts have entered into a process of rapid development, relatively independent from the decentralization trends in the metropolitan areas and from state economic enterprises. In these provinces, which were previously defined as underdeveloped regions, a fast export-based industrialization process, based on SMEs has been observed and their contributions to the formation of the manufacturing industry of the country has increased dramatically.

The industrial districts, which attract the attention of also the press along with the scholars and the practitioners are often described as Anatolian Tigers with a reference to the fast industrializing countries of Southeast Asia. The main industrial districts in the country are the provinces of Denizli, Gaziantep, Çorum, Kayseri and Kahramanmaras.[14] While the industrial districts in Turkey emerge as alternative development paths to traditional regional centers (or metropolitan cities) and their dependent cities in their hinterland, they also serve to reduce the inequalities across the regions. These provinces contributed significantly to regional development and became regional centers.

Table 1: Manufacturing Industry Establishments, Employment and Value Added (MIEs, MIEMP, MIVA) in New Industrial Districts

| Provinces |

Years |

MIEs |

MIEMP |

MIVA |

GDP |

| Denizli |

1980 |

1.34 |

0.94 |

0.61 |

1.4 |

| 1990 |

1.12 |

1.19 |

0.69 |

1.4 |

|

| 2000 |

3.74 |

3.61 |

1.90 |

1.5 |

|

| Gaziantep |

1980 |

1.61 |

0.94 |

0.41 |

1.2 |

| 1990 |

1.32 |

1.26 |

0.64 |

1.8 |

|

| 2000 |

2.33 |

2.21 |

1.53 |

1.5 |

|

| Çorum |

1980 |

0.64 |

0.27 |

0.13 |

0.7 |

| 1990 |

0.91 |

0.36 |

0.13 |

0.8 |

|

| 2000 |

0.78 |

0.44 |

0.24 |

0.7 |

|

| Kahramanmaras |

1980 |

0.22 |

0.25 |

0.14 |

1.1 |

| 1990 |

0.46 |

0.42 |

0.22 |

1.1 |

|

| 2000 |

0.60 |

0.71 |

0.39 |

0.9 |

|

| Kayseri |

1980 |

1.17 |

1.83 |

1.45 |

1.2 |

| 1990 |

1.23 |

1.83 |

1.05 |

1.1 |

|

| 2000 |

1.60 |

2.22 |

1.74 |

1.2 |

|

| Other Provinces |

1980 |

95.02 |

95.77 |

97.26 |

94.3 |

| 1990 |

94.96 |

94.95 |

97.27 |

93.9 |

|

| 2000 |

90.94 |

90.81 |

94.21 |

93.9 |

|

| Turkey |

1980-2000 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

(1) The manufacturing industry includes workplaces employing 10 + employees.

Source: State Institute of Statistics Database

The specialization of districts in particular sectors or products, permitting small sized enterprises such as textiles, has contributed to a rapid increase in shares of new establishments and higher employment in industrial districts throughout these regions between 1980 and 2000.[15]Map 2: New Industrial Districts in Turkey

The emergence of the new industrial districts in Turkey are defined as small and rustic towns, which displayed the ability to utilize the advantages presented by global transformations in developing countries and regions.[16] This model has been evaluated as the take-off of the Anatolian small and medium sized cities[17] and as an alternative to the development model based on large cities. For example, according to Eraydin, “the first leap in Denizli, Gaziantep and Çorum dates back to 1980s and the fast economic growth had appeared as a result of the mutual interaction between liberal macro-economic policies and local accumulated capacity and the policies nourishing local dynamics.”[18]

One of the most significant aspects of the emergence of the flexible specialization model in production organizations is the increase of the importance of SMEs in the economy. As can be seen in Table 2 below, an important part of the manufacturing industry increases between 1980 and 2000, were realized in SME groups, employing 10-49 and 50-199 employees.

Table 2: Distribution of Manufacturing Industry Enterprises (MIEs) in New Industrial Districts (According to Size Groups)

| Provinces |

MIEs Groups |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|||

| MIEs |

% |

MIEs |

% |

MIEs |

% |

||

| Denizli |

10-49 |

88 |

1.34 |

55 |

0.95 |

268 |

3.84 |

| 50-199 |

22 |

1.53 |

25 |

1.21 |

95 |

3.23 |

|

| 200+ |

7 |

1.02 |

19 |

1.83 |

53 |

4.41 |

|

| Total |

117 |

1.34 |

99 |

1.12 |

416 |

3.74 |

|

| Gaziantep |

10-49 |

116 |

1.76 |

70 |

1.21 |

174 |

2.50 |

| 50-199 |

16 |

1.11 |

32 |

1.54 |

60 |

2.04 |

|

| 200+ |

8 |

1.17 |

15 |

1.45 |

25 |

2.08 |

|

| Total |

140 |

1.61 |

117 |

1.32 |

259 |

2.33 |

|

| Kayseri |

10-49 |

68 |

1.03 |

59 |

1.02 |

94 |

1.35 |

| 50-199 |

19 |

1.32 |

29 |

1.40 |

58 |

1.97 |

|

| 200+ |

15 |

2.19 |

21 |

2.03 |

26 |

2.16 |

|

| Total |

102 |

1.17 |

109 |

1.23 |

178 |

1.60 |

|

| Çorum |

10-49 |

52 |

0.79 |

59 |

1.02 |

52 |

0.75 |

| 50-199 |

3 |

0.21 |

20 |

0.97 |

32 |

1.09 |

|

| 200+ |

1 |

0.15 |

2 |

0.19 |

3 |

0.25 |

|

| Total |

56 |

0.64 |

81 |

0.91 |

87 |

0.78 |

|

| K. Maras |

10-49 |

15 |

0.23 |

31 |

0.54 |

43 |

0.62 |

| 50-199 |

2 |

0.14 |

3 |

0.14 |

15 |

0.51 |

|

| 200+ |

2 |

0.29 |

7 |

0.68 |

10 |

0.83 |

|

| Total |

19 |

0.22 |

41 |

0.46 |

68 |

0.61 |

|

| Other Provinces |

10-49 |

6247 |

94.85 |

5488 |

95.24 |

6341 |

90.95 |

| 50-199 |

1375 |

95.69 |

1963 |

94.74 |

2684 |

91.17 |

|

| 200+ |

651 |

95.18 |

973 |

93.83 |

1085 |

90.27 |

|

| Total |

8273 |

95.02 |

8424 |

94.96 |

10110 |

90.93 |

|

| Turkey |

10-49 |

6586 |

100 |

5762 |

100 |

6972 |

100 |

| 50-199 |

1437 |

100 |

2072 |

100 |

2944 |

100 |

|

| 200 + |

684 |

100 |

1037 |

100 |

1202 |

100 |

|

| Total |

8707 |

100 |

8871 |

100 |

11118 |

100 |

|

Source: State Institute of Statistics Database (2004)

Another factor, which distinguishes the new industrial districts in Turkey from other cities, is the advantage of accumulation they possessed before the outward orientation development strategy period. While the outward orientation process emphasized particular sectors in the country, the process of sectoral specialization has increased in the cities defined as new industrial districts, in particular Denizli and Gaziantep. Just like the districts in the Southern Europe and Italy, a local development model based on flexible specialization, has brought the industrial system in all districts to a competitive structure. Despite their differences in articulation to international markets, they have benefited from the advantages of outward orientation as the pioneering provinces in the outward orientation process.

Table 3 shows the distribution of manufacturing industry by the sectors. As seen from the table, after 1980s specialization tendencies have increased especially in the textile sector and the processes of horizontal integration and flexible specialization between the SMEs have gained impetus in sectors such as textiles, foodstuffs and automotive. Sectoral specialization trends can be observed regarding textiles in Kahramanmaras, stone and earthenware industry in Çorum, and forestry products and furniture in Kayseri. Along with the sectoral specialization, the flexible specialization trends based on inter-firm networks, especially in Denizli, has increased.

Table 3: Sectoral Breakdown of Manufacturing Industry in New Industrial Districts| Provinces |

Sectors |

MIEs |

MIEMP |

MIVA |

||||||

| 1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

||

| Denizli |

Textile |

1.72 |

1.54 |

8.37 |

2.08 |

2.24 |

8.43 |

1.51 |

1.67 |

7.82 |

| Metallurgy |

5.08 |

3.64 |

5.22 |

0.67 |

1.02 |

2.26 |

0.26 |

0.99 |

2.22 |

|

| Earth-Stone |

0.67 |

1.02 |

2.81 |

0.33 |

1.69 |

3.22 |

0.05 |

1.30 |

2.10 |

|

| Chemistry |

0.89 |

0.97 |

1.86 |

0.60 |

0.43 |

0.89 |

0.10 |

0.09 |

0.37 |

|

| Total |

1.34 |

1.12 |

3.74 |

0.94 |

1.19 |

3.61 |

0.61 |

0.69 |

1.90 |

|

| G.antep |

Textile |

2.67 |

1.71 |

4.30 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

5.10 |

1.04 |

2.16 |

6.85 |

| Foodstuffs |

1.62 |

1.64 |

2.57 |

0.87 |

0.96 |

1.23 |

0.54 |

1.20 |

1.05 |

|

| Chemistry |

0.89 |

0.97 |

1.86 |

0.60 |

0.43 |

0.89 |

0.10 |

0.09 |

0.37 |

|

| Paper |

0.82 |

1.17 |

1.77 |

0.36 |

0.53 |

1.13 |

0.27 |

0.13 |

0.51 |

|

| Total |

1.61 |

1.32 |

2.33 |

0.94 |

1.26 |

2.21 |

0.41 |

0.64 |

1.53 |

|

| Kayseri |

Forestry Prod |

0.85 |

0.63 |

4.85 |

0.26 |

- |

19.47 |

0.05 |

- |

25.11 |

| Metallurgy |

1.42 |

2.86 |

2.61 |

1.46 |

1.43 |

1.51 |

1.87 |

1.67 |

4.25 |

|

| Metal Tools- Machinery |

2.03 |

2.05 |

2.43 |

1.12 |

2.00 |

2.59 |

0.48 |

0.62 |

1.27 |

|

| Foodstuffs |

1.03 |

1.58 |

1.76 |

1.33 |

1.69 |

1.10 |

1.28 |

0.95 |

1.03 |

|

| Total |

1.17 |

1.23 |

1.60 |

1.83 |

1.83 |

2.22 |

1.45 |

1.05 |

1.74 |

|

| Çorum |

Earth-Stone |

6.38 |

7.58 |

5.15 |

2.64 |

3.31 |

2.98 |

1.34 |

0.97 |

0.49 |

| Metallurgy |

0.20 |

0.52 |

1.31 |

- |

- |

0.18 |

- |

- |

0.08 |

|

| Foodstuffs |

0.49 |

0.74 |

0.94 |

0.15 |

0.20 |

0.51 |

0.18 |

0.09 |

0.73 |

|

| Metal Tools-Machinery |

0.22 |

0.40 |

0.46 |

0.05 |

0.14 |

0.25 |

0.02 |

0.06 |

0.14 |

|

| Total |

0.64 |

0.91 |

0.78 |

0.27 |

0.36 |

0.44 |

0.13 |

0.13 |

0.24 |

|

| K.Maras |

Textile |

0.18 |

0.64 |

1.00 |

- |

0.93 |

1.57 |

- |

1.02 |

2.02 |

| Foodstuffs |

0.54 |

0.95 |

0.88 |

0.12 |

0.64 |

0.70 |

0.04 |

0.34 |

0.20 |

|

| Metallurgy |

0.61 |

0.52 |

0.52 |

0.06 |

- |

- |

0.01 |

- |

- |

|

| Metal Tools-Machinery |

0.09 |

0.20 |

0.46 |

- |

0.07 |

0.16 |

- |

0.03 |

0.04 |

|

| Total |

0.22 |

0.46 |

0.60 |

0.25 |

0.42 |

0.71 |

0.14 |

0.22 |

0.39 |

|

| Turkey |

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Source: State Institute of Statistics Database (2004)

Although the districts in Turkey made a leap after the 1980s, the cornerstones of the industrialization of these cities had been laid out in the past and the current industrial structure has been formed as a result of an accumulation process. Table 3 also shows that these cities have a significant portion in Turkey's industrial indicators and had been specialized on certain sectors prior to 1980.

Another factor, distinguishing new industrial districts from other provinces is their level of outward orientation and their performances in international trade. Since the emergence of the districts is related to the globalization and outward orientation, their performances in international trade gain importance. The export data on the 5 districts, including the period between 1995-2001 shows that these cities have achieved considerable success in foreign trade. While the increase in the total exports of Turkey is 50 % between 1995-2001, the exports from Denizli have increased five fold, in Gaziantep and Kayseri two fold and Kahramanmaras seven fold. Only Çorum, among the districts has not shown remarkable performance.

Table 4: Export Performance of the New Industrial Districts (Thousand US Dollar)| Provinces |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

| Denizli |

184,864 |

171,816 |

228,701 |

228,893 |

244,653 |

269,169 |

443,485 |

| Gaziantep |

199,405 |

174,324 |

279,938 |

319,736 |

301,940 |

309,321 |

384,564 |

| Çorum |

20,866 |

16,333 |

12,763 |

20,115 |

18,132 |

18,369 |

18,896 |

| Kayseri |

155,118 |

195,225 |

216,452 |

232,707 |

197,121 |

234,692 |

296,304 |

| K.Maras |

18,926 |

23,169 |

65,443 |

90,461 |

125,507 |

103,006 |

134,212 |

| Unknown |

310,496 |

278,282 |

281,961 |

301,238 |

459,525 |

398,319 |

|

| Turkey |

21.481.929 |

23,224,465 |

26,261,072 |

26,973,978 |

26,587,225 |

27,774,906 |

31,342,035 |

Source: Undersecratariat of Foreign Trade Database (2003)

General Features of the New Industrial Districts

The differences in the geographical locations and the intra-regional division of labor of industrial districts have inevitably caused the emergence of different regional models. Gaziantep, a historical regional center in which the commercial activities have been concentrated on history and Denizli as a hinterland of Izmir, illustrate two different models. Similarly while Kayseri has been a commercial and industrial center for ages, Çorum and Kahramanmaras have been defined as relatively less developed provinces. Although there are common aspects in the evolution of the local development processes, the phases experienced in accordance with the local peculiarities and their current industrial and economic structures, display differences. Along with the differences derived from geographical location, local resources, local socio-cultural structures and relations and the differences in local knowledge and skills yield the present differences in local economies (sectoral specialization, industrial organization, exportation structures, etc). All these differences influence their articulation of models to the national and international markets, which produces an increase in diversity, thus making it difficult to define within the framework of a single model. In short, industrial district models in Turkey display tremendous heterogeneity.

A leading example of industrial districts in Turkey is Denizli. Denizli, located in the Aegean region, may be defined as a specialized province, considered underdeveloped compared to the surrounding developed provinces on the basis of a product (towels-bathrobes) and its orientation to the international markets. Many factors have played various roles in its industrialization process. A traditional weaving industry and other artisanal activities has increased local knowledge and capital accumulation and this accumulation has formed the core of today's industry in Denizli. The geographic location of the region, the presence of the raw material resources, the behaviors and the attitudes of the entrepreneurs, co-operatives and multi partnership worker companies (MPWCs), agglomeration advantages and incentives are the factors, all contributed to the development of industry in Denizli. In addition, state policies have played a significant role in their local development process. Denizli has obtained important industrial incentives. The establishment of Organized Industrial Estate and provision of cheap industrial plots with infrastructure has encouraged the development of industry. Again in the 1970s, the MWPCs, established by the workers from Denizli working abroad, have played significant roles in industrialization.

Another industrial district example is Gaziantep. The historical development process, and location of Gaziantep are quite different from Denizli. While Denizli was a relatively underdeveloped province of the developed Aegean Region, Gaziantep has functioned as a commercial and industrial center for the underdeveloped South-eastern Anatolia Region. The analogy of a “cathedral in the desert” is best suited for Gaziantep. Within this framework, Gaziantep may be defined as a specialized regional center, which is more developed compared to the underdeveloped provinces surrounding it. Its industrial orientation is to the markets of the underdeveloped and developing countries. The local development process of Gaziantep has also developed in a cumulative process. In this process, The facility for entrepreneurship based on artisanship and tradesmenship, local agricultural potentials, geographical location and regional division of labor together with state supports and the outward orientation process experienced within the past few decades have all played a crucial role.

A third industrial district is Çorum. Located between Ankara and Samsun, Çorum, although it is close to Ankara, has followed a path of development, which is totally independent from the decentralization trends in Ankara. Furthermore, it has displayed a local development performance based on endogenous resources. The local development model of Çorum is evaluated as a bottom-up development, it does not contain state investments and is completely based on local entrepreneurs and resources. Industry in Çorum, which was transformed from a rural to urban structure has developed in the sectors of bricks and textiles. However, although there are no state economic enterprises in Çorum, incentives in the 1980s played an important role in the emergence of Çorum as an industrial district. The province obtained the opportunity to make investments on new sectors by increasing its capital accumulation. The local resources, the know-how and capital accumulation, concentrated on certain sectors have played an important role in its development. As a result of the accumulations and experiences obtained during this process, more and more entrepreneurs have established their second and even third factories. On the other hand, inter-firm networks in Çorum are relatively less developed and this handicap inhibits reaching the international markets, as seen export figures. Informal channels (relations of spouses, friends and relatives) are used in the provision of international relations. The immigrant workers of Çorum origin, who work abroad, contribute to the economy of Çorum, positively. It is expected that, the networks formed with the workers abroad will help the province to become an export zone.

Another industrial district is Kahramanmaras. While Kahramanmaras was an underdeveloped province in terms of its economic and social characteristics, with the rapid development in the industry, starting from the beginning of 1980s it has transformed from a traditional agriculture-based structure to an industrialized province. In the local economic development process, lead by SMEs, the developments in many sectors, the textile sector in particular, has created an economically dynamic city. The main sectors of specialization of the industry of Kahramanmaras are textile, metal tools, and machinery. The cornerstone of the industry of the province is formed by yarn, weaving, dye, and ready-to-wear clothes companies. While there were only three textile factories, including one belonging to state in Kahramanmaras until 1980, entrepreneurs of Kahramanmaras have started to benefit from the privileges provided with the inclusion of the province to Priority Development Areas in 1968 and the foreign trade incentives implemented after the 1980s.

The last industrial district example is Kayseri. Kayseri was a small industrial city in the past. With its increasing industrial performance especially after 1980s, it has taken its place among the provinces defined as “new industrial districts.” Private sector investments, which were established as small enterprises in the import-substitution era following the 1950s, increased both in numbers and in sizes in the 1970s. The sectoral specialization tendencies in furniture, textiles and metallurgy that have a historical legacy have emerged in the 1980s. The presence of a subcontracting production model and inter-firm cooperation tradition in those sectors has played a significant role in the industrial growth. One of the most important factors in the success of Kayseri is its historically rich entrepreneurship and industry base, which dates back to early ages. The lack of fertile agricultural areas around Kayseri has caused the development of the culture of commerce and production on the basis of trade and industry. Therefore, the local socio-cultural structure has developed around the values and norms of artisans. Another important factor in the local development process of Kayseri is public sector investments made after the foundation of the Republic. In the province, which acquired a railroad and power plant at the end of 1920s, large scale public investments have been established in the same years, which assembled or repaired vehicles such as aircraft and tanks. These investments have contributed to the industrial development after the 1950s, especially in terms of qualified labor, raw material necessary for production, and the development of the subsidiary industries in sectors like metallurgy and textile. Following the 1980s, there has been an increase in the number of the large enterprises belonging to the private sector. An important reason for this is the incentive system implemented after 1985. Moreover, the establishment of organized industrial estates (OIEs) and the grant of priority development areas status to the OIEs within the framework of the incentive system have caused a rapid increase in the number of large establishments in Kayseri.

Conclusion

Although the problem of regional disparities still persists in the macro-geography of the country, considerable changes have emerged in the spatial distribution of industry as a result of the macro-economic political changes in the 1980s. Among them the most striking tendency is the new industrial districts, which have emerged spontaneously in various regions of Anatolia, based on endogenous factors. The four main factors, distinguishing the five industrial districts, are: (1) The widespread existence of local entrepreneurs and investments, (2) Their successful local development performance in the outward-oriented era, (3) specialization in particular sectors and widespread existence of autonomous SMEs in contrast to large vertically organized corporations, and (4) high export performance. Although the five industrial districts in Turkey display differences with respect to these characteristics, each have traveled through different local development paths and the accumulations they have achieved in the past also help to explain their present industrial and economic structures. The industrial district models in Turkey demonstrate heterogeneity. The districts, which possess different accumulations in the past, have experienced different processes of articulation to foreign markets in the outward-orientation era. However, each has been able to successfully internalize global opportunities with local entrepreneurship and a reserve stock of knowledge and skills.

The emergence of the new industrial districts is significant in many respects. The first is the common belief that while the regional disparities across the country increased and state policies aiming to remove disparities fail, the industrial districts displayed development with a bottom-up model. This development occurred without benefiting from the top-down state policies and independent from the decentralization in the metropolitan centers. This situation has created doubts about the traditional role of the state in industrialization, economic development and removal of regional disparities. The emergence of the industrial districts has yielded discussions within the framework of the contrasts between the top-down central government and bottom up local dynamics and public and private sectors. In addition, they are seen as a development model based on local dynamics.

Secondly, fact that the new industrial districts developed on the basis of SME clusters have crushed the conventional spatial development trends in Turkey based on metropolitan cities and they have conveyed the development to small and medium sized Anatolian cities. The districts that have followed a development path within the framework of their own endogenous potentials have succeeded in becoming a center of attraction and have started to serve a significant function in the transfer of development to the less developed Anatolia. By disrupting the unbalanced development tendencies on the national level, emerging around a few growth poles, they have yielded an alternative development tendency. While the tendency of state-supported provinces retreats, the direction of the decentralization dynamics in the metropolitan cities spread towards the relatively developed western regions, instead of “leaping” to Anatolia. This pattern of development in the regions has yielded discussions that inquire whether the new industrial districts could be a local and national development model as is the case in other countries.

While the state in Turkey has focused on the top-down policies in the field of development, such as growth poles (the de facto examples could be regarded as the cities based on state economic enterprises and the de jure ones are 16 regional centers across the country selected according to the results of the Research called as “The Hierarchy of Location Centers” in 1982), regional development plans and priority development areas, the emergence of the industrial districts has increased the significance of the SMEs and the small and medium-sized cities. The basic reasons for this are: (1) the failure of the top-down development policies of the state and the increase in the regional disparities, (2) decreasing state allocations for regional development, and (3) the failure of the state in implementing region-specific policies, since it possesses a hierarchical and bureaucratic structure. All these have led to inquiries into what kind of a development model was followed by the districts and could this model be applied to other territories.

The effects of the globalization process and the adaptation of European Union regional development policies as the two main external dynamics will seem to be more effective on Turkey in the near future. Both tendencies are apt to emphasize the significance of the local dynamics and bottom-up development initiatives. Considering the possible effects of both processes, taking into account recent development models and the current internal dynamics of new industrial districts will help to develop more effective local development policy system and a new division of labor between central and local governments in Turkey.

* Dr. Metin Özaslan is planning expert at the State Planning Organization (DPT), Turkey.

[1] State Planning Organization (SPO), Economic and Social Indicators (1950-2004) (Ankara: SPO, 2005).

[2] Metin Özaslan, The Emergence of New Industrial Districts in Turkey: Denizli and Gaziantep Cases. Unpublished PhD Thesis (The University of Nottingham, 2004).

[3] M. Piore and C.F. Sabel, The Second Industrial Divide. (New York: Basic Books, 1984); M. Storper, and A. J. Scott (eds.), Pathways to Industrialisation and Regional Development. (London: Routledge, 1992); Ash Amin (ed.), Post-Fordism, Third edition. (Blackwell Publishers Inc., 1996); Michael H Best, The New Competition: Institutions of Industrial Restructuring, (Oxford: Polity Press, 1990); M. Porter, The Competitive Advantage of Nations (New York: The Free Press, 1990); F. Pyke, G. Becattini and W. Sengenberger (eds.), Industrial Districts and Inter-firm Co-operation in Italy. (Geneva: International Institute for Labour Studies, 1990); Frank Pyke and Werner Sengenberger (eds.), Industrial Districts and Local Economic Regeneration: Research and Policy Issues (Geneva: International Institute of Labour Studies, 1992).

[4] M. Tamer Müftüoglu, “Türkiye'de girisimcilik. DPT, DIE ve SPK” (Organizatörler) Yeni Yerel Sanayi Odaklari (Denizli-Gaziantep) Uluslararasi Semineri, Ankara, 23-25 September 1998.

[5] Turkey has entered the Planning Era since the beginning of the 1960s. From 1963 until today 8 five-year development plans have been put into practice.

[6] In the context of integrating sectoral priorities of development plans with spatial dimensions, several regional development plans aiming at reducing interregional development disparities and realizing sustainable development have been prepared in the Planned Era. The foremost among these are; East Marmara Planning Project, Antalya Project, Çukurova Region Project, Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP), Zonguldak-Bartin-Karabük Regional Development Project, Eastern Anatolia Project and Regional Development Plan for the Eastern Black Sea Region. None the less, excluding GAP, regional development projects prepared until recent years, could not be implemented effectively.

[7] One of the objectives of the incentive schemes regulating the State Investment Aids has been the implementation of specific incentive policies for economically and socially less developed regions to ensure their development. Within this scope, Priority Development Areas were determined and incentive policies were put into practice for these regions. Priority Development Areas covers 49 provinces and 2 districts today.

[8] A way of improving infrastructure for industrial enterprises in Turkey has been to establish Organised Industrial Estates (OIE) for middle-scale industries and Small Industry Sites (SIS) for small-scale industries. OISs and SISs make considerable contributions to the localization of industry by means of providing suitable environment for the improvement of local SMEs and thus also contributing to the balanced distribution of industry among regions.

[9] DPT, Türkiye'de Yerlesme Merkezlerinin Kademelenmesi: Ülke Yerlesme Merkezleri Sistemi. (DPT: Ankara, 1982)

[10] Metin Özaslan, “GAP ve Sosyo-Ekonomik Gelisme,” GAP ve Sanayi Kongresi, TMMOB Makina Mühendisleri Odasi, Diyarbakir, 2005.

[11] B. Dincer and M. Özaslan, Ilçelerin Sosyo-Ekonomik Gelismislik Siralamasi. (Ankara: Devlet Planlama, 2004a); B. Dincer and M. Özaslan, Regional Disparities and Territorial Indicators in Turkey: Socio-Economic Development Index (SEDI). Paper presented to the OECD Working Committee on Regional Indicators Workshop in Portugal. (31 May-1 June 2004b); B. Dincer and M. Özaslan, and T. Kavasoglu, Illerin ve Bölgelerin Sosyo-Ekonomik Gelismislik Siralama (Ankara: DPT, 2003).

[12] In recent years, for the purposes of more efficient analysis and implementation of regional development policies and ensuring harmonization with the European Union, NUTS classification is introduced. Within this scope 12 NUTS I and 26 NUTS II regions were determined in Turkey. Another initiative has been to establish “development agencies” on the basis of 26 NUTS II regions, with the purpose of ensuring bottom-up development.

[13] According to Turkey-EU pre-accession financial cooperation a number of Regional Development Programmes have been initiated, in recent years. The first Integrated Regional Development Programme to mention among them is, “Eastern Anatolia Development Programme” focusing on TRB2 NUTS II Region (comprising Van, Bitlis, Mus and Hakkari provinces) aims to reduce the regional disparities, ensure sustainable economic and social development and increase the job opportunities in the region and income level of the population in rural areas. The other Integrated Regional Development Programme which is also in implementation phase is “Regional Development Programme in TR82 (Çankiri, Kastamonu and Sinop) TR83 (Amasya, Çorum, Samsun and Tokat) and TRA1 (Erzurum, Erzincan and Bayburt) NUTS II Regions.” The Programme is concentrated on such priority areas; supporting SMEs and other local development initiatives, developing small-sized infrastructure, and building local capacities. In addition, “Regional Development Programme in TRA2 (Agri, Ardahan, Igdir and Kars), TR72 (Sivas, Kayseri and Yozgat), TR52 (Karaman and Konya) and TRB1 (Bingöl, Elazig, Malatya and Tunceli) NUTS II Regions” is planned to start implementation in the last quarter of 2005. The Programme is also focus on the same targets of the above programmes. Furthermore, The Cross-border Cooperation programme started between Bulgaria and Turkey, aims at reinforcing cross-border economic, social and cultural links, contributing to the improvement of economic potential of the border regions. Infrastructure, environment, economic development and technical assistance have been the main priority areas in Interreg III/A Programme between Turkey and Greece. With the “Twinning” programme, it is aimed to provide technical support for the institutions and organizations in Turkey in the establishment of necessary mechanisms to implement and improve the regional policies and in the preparation and implementation of the projects supported by EU funds.

[14] The five industrial districts analysed in this paper have been defined within the framework of the following criteria. The new industrial districts (1) should be developed using their own local entrepreneurs and resources, instead of decentralised non-local entrepreneurs and capital from other regions, (2) should display a successful growth performance in terms of industrial indicators after 1980, (3) should be specialised in particular sectors on the basis of SMEs, and (4) should be oriented towards foreign markets and have higher export performance.

[15] On the other hand, although the shares of the industrial districts in total establishments have increased compared to other provinces, this increase has not been as much as the one in manufacturing industry value added. One of the main reasons for relatively low value added increase is the search for a competitive power, based on cheap labor. Another reason is the dominance of SMEs in the industrial districts. This situation is also reflected in the gross domestic product (GDP), which is the ultimate indicator of performance.

[16] Melih Pinarcioglu, Development of Industry and Local Change (Ankara: METU, 2000).

[17] Gül Berna Özcan, Small Firms and Local Economic Development in Turkey: Three Case Study Areas, Unpublished PhD Thesis, London School of Economics, 1993.

[18] Ayda Eraydin, Yeni Sanayi Odaklari: Yerel Kalkinmanin Yeniden Kavramsallastirilmasi (Ankara: ODTÜ, 2002), p.73.