|

|

|

|

Strategic Analysis:

A Monthly Journal of the IDSA

Pakistan’s Kashmir Policy: Objectives and Approaches

Smruti S. Pattanaik

*

, Research Officer, IDSA

Abstract

The underlying factors of Pakistan’s Kashmir policy have remained unchanged since the first Kashmir war. Its diplomatic efforts both bilaterally as well as raising the issue at various international fora have been limited to malign India and to portray that bilateral approach have failed. Also, it seems to lack a genuine desire to resolve the problem mutually with India. It has not abandoned a militaristic approach to resolve the issue. Pakistan though forcefully advocates the implementation of the UN resolution, its lack of sincerity to implement Clause II of the UN resolution can be seen in its efforts. Its militaristic approach to resolve the Kashmir issue clearly shows its lack of interest in adhering to the UN resolution. While articulating about the wishes of the Kashmiri people it has followed its own political agenda. Whenever it talks of failure of bilateralism to solve the Kashmir issue, it can be interpreted as the non-resolution of the issue on Pakistan’s terms. Pakistan’s persuasion of its nationalistic agenda within the framework of bilateralism has resulted in diplomatic stalemates. This paper analyses Pakistan’s objective and approache towards the Kashmir issue and, given the changing international scenario, the possible options for its resolution.

The Agra summit and the failure of bilateral dialogue due to Pakistan’s obsession to discuss only the Kashmir issue raises a few pertinent questions. The first question that strikes one’s mind is why Pakistan perceives Kashmir as the core issue and consequently holds the gamut of bilateral relations hostage to this single issue? Second, why has the Kashmir issue graduated to a one-point agenda in Pakistan’s bilateral relations with India in the 1990s? Third, what has been Pakistan’s approach for a solution to this issue in a historical perspective and what would be its future approach to the resolution of the issue? And lastly, can it pursue its decade old policy of low intensity conflict in the post-September 11 political developments?

These questions have assumed significance because bilateral relations have not moved forward due to Pakistan’s single minded pursuit of its political agenda on the Kashmiri issue.

An analysis of Pakistan’s policy perspective on the Kashmir issue suggests that it has used both military means as well as diplomatic approaches. Whenever Pakistan felt that its militarily strength would deliver its objective of wresting Kashmir from India, it did not hesitate to use force. However, whenever it has felt that it is weak or has realised that international public opinion would not allow it to have a military approach, it has talked of bilateral discussions. Pakistan has constantly called for third party intervention and feels that its close allies would favour her in the arbitration. To prove that bilateral negotiations are futile, Pakistan has not only pursued its single point agenda but refuses to discuss other bilateral issues. This has derailed the bilateral dialogue. Pakistan also, while pursuing its ‘core issue’ has been uncompromising in its attitude and talks only of plebiscite and the UN resolutions. Since India does not agree to this formula, Pakistan tries to portray to the world community that bilateralism would not resolve the issue. This paper analyses some of the questions raised above in order to understand Pakistan’s objectives and strategies and their implications to the Indian approach.

Kashmir Issue: Perceived Relevance to Pakistan

Many Pakistanis regard Kashmir’s accession to India as a British conspiracy and violation of the principle of partition based on the two-nation theory. The most important underlying factor that has been side-lined is that it was only British India that was to be partitioned according to the two-nation theory and princely states were outside the purview of partition. In a Conference of the State Rulers and their representatives Mountbatten said, on July 25, 1947 while referring to the Indian Independence Act of 1947, it “releases the States from their obligations to the Crown. The States have complete freedom-technically and legally they are independent”. He further added, “You cannot run away from the Dominion government which is your neighbour any more than you can run away from the subjects for whose welfare you are responsible”. 1 Those Pakistani political analysts who talk of the conspiracy theory generally refer to the award of Gurdaspur to India which gave a land corridor to New Delhi to have access to Kashmir. 2 According to a Pakistani scholar, both Mountbatten and the Congress leaders had agreed to the creation of Pakistan on the clear perception that Pakistan will have to ask for reunion with India. Accession of Kashmir to India formed an important part of the strategy to bring about this reunion. 3 This reunion “was carefully planned to be achieved by so demarcating the final boundaries of Pakistan that she will not only be denied a large number of areas which had Muslim majorities but her economy will be greatly damaged”. 4 According to this perception Kashmir is geo-strategically situated and it can be used to cripple Pakistan economically and militarily. Thus, its geo-economic significance makes it necessary that Kashmir accedes to Pakistan. In light of this, a Pakistani defence analyst with reference to the Mangla headwork on the river Jhelum, which is a few miles away inside the Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK), points out that the presence of Indian troops in Kashmir could constitute a direct threat from the rear to the North West Frontier Province (NWFP). Thus, Kashmir can be used to launch an offensive by the Indians where as the possibility of a Pakistani attack on Kashmir is very remote 5 . According to such articulation, Pakistan cannot survive without Kashmir. The Pakistani military and political leaders believe that the economic well being of Pakistan is inalienably linked to Kashmir. 6 Sardar Abdul Qayyum Khan, President, ‘Azad Jammu and Kashmir’ said “ . . . Pakistan cannot exist as an independent entity by withdrawing its claim on Kashmir. It will be turned into a virtual hostage to India, and its lease of life will depend upon the period which India will allow it to exist”. 7

Ayub Khan defined Pakistan’s foreign policy as moral in content and based on security, development and preservation of the ideology of Pakistan. 8 An analysis of his conception and Pakistani articulation on the issue of ideology suggests that Pakistan has construed Kashmir as a part of its Islamic identity. Explaining further he said that the security of Pakistan requires a fair solution of the Kashmir problem. 9 The term ‘fair solution’ in the Pakistani context is interpreted as the implementation of the UN resolution or accession of Kashmir to Pakistan on the basis of the two-nation theory. The position of Pakistan and approach to what is considered as ‘fair solution’ can be understood from the statement that Z.A. Bhutto made in the UN Security Council, “The people of Jammu and Kashmir are part of the people of Pakistan in blood, in flesh, in life, in culture, in geography, in history and in every way and in every form . . . If necessary Pakistan would fight to the end”. 10 Pakistan’s security problems arise both from history and geography and have both ideological and political dimensions. According to a scholar, the historical problem lies with “the unfinished business of partition . . . in the form of the unresolved dispute of Kashmir”. 11 Basing their argument on such interpretation of historical events, some Pakistani analysts argue that by applying both the principle of two-nation theory and geographical contiguity, Kashmir belongs to Pakistan. These views generate opinions such as, “ . . . Kashmir’s accession to Pakistan was not simply a matter of desirability but of absolute necessity for our separate existence.” 12

In addition to these perceptions, Pakistan bases its argument on the UN resolutions. Many Pakistanis are made to believe that Kashmiris would vote for merger with Pakistan in the event of a plebiscite. They also feel that since India is aware of this factor it reneged on its promise of holding the plebiscite. Moreover, Pakistan’s approach towards Kashmir is dictated by the Pakistani army. The role of some sections of the Pakistan army in the 1947 tribal invasion is a known fact. The acceptance of a cease-fire in 1948 by Pakistan became one of the causes of revolt against the government in which the man who is known as the hero of Kashmir, Major Akbar Khan, along with other army officers conspired to overthrow the government. This is, otherwise, known as the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case. With such entrenched belief, support to Pakistan’s Kashmir policy is automatically generated.

Kashmir as the Core Issue and Diplomacy in the 1990s

The 1990s assume significance in the context of both internal politics in the valley and Pakistan’s objectives and approach to the Kashmir issue. Though the issue of Kashmir has always been significant to Pakistan, it, by itself, has never defined its relations with India so rigidly as one sees now. The growing rigidity in Pakistan’s stand can be attributed to a few factors. First, Pakistan believes its involvement in Kashmir after 1989 as a success. According to this belief, its ability to control violence has given Pakistan the capability and influence to dictate peace in the valley. Pakistan’s involvement in Afghanistan was an apprenticeship for its low intensity conflict in Kashmir. The arms and ammunition provided by the CIA and channeled through the ISI (Inter-Services Intelligence) found its way to the Pakistani arms market and finally the society. The easy availability of arms has given a new meaning to the jihadis. Islamic orientation to the whole Afghan conflict not only indoctrinated the mujahideens but also at the same time led them to interpret and perceive the Kashmir conflict through the narrow prism of jihad. Secondly, the withdrawal of the Soviet Union and later its disintegration gave a new meaning to jihad and convinced the Pakistani establishment regarding the capabilities of the well organised mujahideen groups. Pakistan’s strategy was to engage them in a low- intensity conflict in Kashmir with rewarding results. Armed with sophisticated weapons, motivated through religious indoctrination and convinced about their dedication to the cause of Islam and their ultimate victory, this new breed of Islamic jihadis emerged as a new tool to execute the foreign policy objectives of Pakistan. The involvement of these radical Islamic groups had two objectives. First, it would not only save Pakistan from a direct military involvement but at the same time would achieve Pakistan’s objective of inflicting damage to India. Second, according to a Pakistani strategy, it would pressurise India to concede some sort of compromise on the Kashmir issue. Thus, the 1990s not only saw more violence in Kashmir but also continuance of the military option to achieve a solution to the Kashmir issue. The objective is to use low intensity conflict and pose a threat of military escalation to secure internationalisation of the Kashmir issue.

Interestingly, bilateral approach to Indo-Pakistan relations and emphasis on the Simla Agreement became the foreign policy tool of the democratic regime after Zia-ul-Haq’s death. Two reasons can be attributed to this. First, it was Benazir’s father who was one of the architects of the Simla Agreement. Second, the future scenario in Afghanistan was still unpredictable and was evolving, as a result of which a confrontationist attitude towards India would not have helped. These factors prompted Pakistan to look towards a bilateral solution. Rajiv Gandhi’s visit to Islamabad and the various agreements that were signed in December 1988 evoked expectation of close Indo-Pakistan relations. But the new political realities on the ground belied any such hope. As Benazir herself remarked cautiously ”given the checkered history and complexity of our bilateral relations, major breakthroughs should not be expected”. 13 The domestic political compulsions curtailed any drastic change in Pakistan’s approach. For example, Benazir being a woman Prime Minister of an Islamic state faced problem from the religious parties who questioned her legitimacy. In this context, pandering to the religious lobby became important. Thus a hard line on Kashmir became inevitable. Also, her survival in power depended on the army. Given the army’s approach towards India, she could hardly afford to take an independent line on the Kashmir issue. Finally, Article 58 2(b), a clause that was inserted by General Zia in the 1973 Constitution, gave arbitrary power to the President to remove any democratically elected government on charges of corruption. This severely limited her political maneouverability. The evolvement of a troika in Pakistan’s political structure, where the President and the Army Chief worked in tandem, made the Prime Minister to become the executor of policies rather than the formulator. Apart from this, Benazir was clearly told the limits to her power in certain areas of decision-making. The army demarcated the sphere of influence and Pakistan’s Afghan, Kashmir and the nuclear policies were out of bounds for the civilian government. The limitation to her power even after she talked of the Simla Agreement was evident when the Pakistani Senate under Rule 194, adopted a substantive resolution which favoured bilateral talks with India in the spirit of equality and sought resolution of the Kashmir issue by holding plebiscite. 14

The militancy supported by Pakistan led to increased violence in Kashmir. Bilateralism became increasingly irrelevant as a policy for Pakistan since low intensity conflict brought about the required policy dividends. Subsequently, the significance of Simla Agreement as a reference point to bilateral ties became a dead issue. Pakistan saw a role for it in the internal situation of Kashmir. Since the situation was volatile, the objective of the Pakistan army became to engage in low intensity conflict without evoking a general war in Kashmir. 15 While the army executed the Kashmir policy, the civilian government’s foreign policy agenda kept in tandem with the military approach. The increasing political rhetorics emanating from Pakistan derailed the bilateral relations. Moreover, Benazir who had earlier hailed the Simla Agreement and talked of a negotiated settlement, to prove her commitment to the army-led Kashmir policy, reverted to a hardline stand. This provided the army with the required domestic support to execute its policy. Propaganda on human rights violation and publicising the internal dissatisfaction in the valley as an expression of the Kashmiris’ desire to merge with Pakistan, gave many Pakistanis a conviction that low intensity conflict would bring political capital at the negotiating table. Moreover, the religious parties who were marginalised in the 1988 election and were sidelined after the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan found a new lease of life. The Kashmir issue gave a new meaning to their political existence. Thus they again became an appendage of the establishment in executing the Kashmir policy of Pakistan. During this decade the army and the Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI) executed the Kashmir policy whereas the civilian government was allowed to keep the façade of diplomacy alive thus giving the required diplomatic cushioning to the military-led foreign policy. The breaking down of bilateral talks with India in 1994 can be attributed to the overt support to the militants and Pakistan extended its decision to raise the Kashmir issue at the Geneva Human Rights Convention. During this intervening period, till the resumption of bilateral dialogue in 1997, Nawaz Sharif imposed a Kashmir tax and established a Kashmir fund and Benazir gave a call for thousand years of war with India to wrest Kashmir. The civilian government was no doubt used as an instrument in charting the army’s Kashmir policy.

The resumption of structured bilateral dialogue in 1997 could not bring any diplomatic gains because the approaches to bilateral relations of both the countries were divergent. The Lahore declaration ended with a bitter note in Kargil and the military takeover in October 1999 saw the end to Pakistan’s commitment to both the Simla and Lahore agreements. Kargil underlined the fact that Pakistan has not given up the military approach to the solution of the Kashmir issue. The faith of the political elites on the ability of the militants to deliver can be understood from the following observation made by Pakistani columnists. The Kargil issue was perceived as ”an inglorious end to what was to be a glorious adventure . . . ”. 16 According to Tehmina Ahmed “if we could have held our ground, the offensive might have led to the sort of advantage like one that India gained in its own land grabbing exercise in Siachin.”. 17 This view itself attests the fact that there is immense faith in the capability of the militants to deliver.

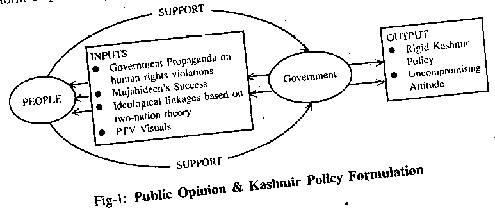

The most important aspect is, where from do the governing elites derive support to their Kashmir policy? Why is opposition of the civil society to Pakistan’s Kashmir policy feeble? Does this imply that the civil society supports government policy? Why is the civilian government not talking of compromise on the Kashmir issue? Perhaps the answers to these questions can be found in the manufactured public opinion. The system theory, especially the one propounded by David Easton can be applied to understand the public opinion formation in Pakistan on the Kashmir issue. This theory talks of inputs from the government and feedback to the system in the form of public opinion that determines the output in terms of policy formulations. However, the feedback that is generated and conveyed to the government is largely dependent upon the inputs. In the case of Pakistan, due to restricted people-to- people interaction and limited exposure, people largely rely on the government’s information. The model shown in Fig-1, explains the formulation of Pakistan’s Kashmir policy.

The importance of Kashmir in Pakistan can be appreciated from the fact that the civilian government while presenting their balance sheet on governance makes a point to underline their achievement in Kashmir. The hardline stance adopted by the government is portrayed as a positive achievement. This itself erodes the basis for any mutual understanding between India and Pakistan to resolve the issue. This is because an uncompromising attitude is interpreted as guarding the ‘national interest’ of Pakistan by withstanding pressure from various sources.

Pakistan’s Strategy: A Historical Analysis

A historical perspective of Pakistan’s Kashmir policy reflects an approach of pressurising India by adopting a strategy of military option and internationalisation. Pakistan’s commitment and belief to the UN resolution is based on political rhetoric. This can be established from the fact that Pakistan was not sincere in implementing the clauses of the UN resolution. Pakistan bases its argument on Clause III of the 1948 UN resolutions without concurrent reference to Clause II of the resolution. Pakistan’s reluctance to withdraw its troops and tribesmen led to a situation where implementation of the UN resolution was impossible. The controversy over the quantum of force to be present in Kashmir before the plebiscite also contributed to the non-implementation. Though many Pakistani analysts blame India for not implementing the UN resolution, the White Paper on Jammu and Kashmir presented to the Pakistan National Assembly squarely puts the blame on the indecisiveness of the government of Pakistan. It says, “the governments in office in Pakistan lapsed into passivity regarding Kashmir. They were deflected into concerns other than the utilisation of the agency of the United Nations for furthering the process that would have led to a plebiscite in Jammu and Kashmir”. 18

Though Pakistan argues for implementation of the UN resolution, its basic posture on having military solution to the Kashmir issue has not changed. Pakistan’s faith in the UN resolutions is thus questionable. This is evident when Pakistan re-enacted the 1948 tribal invasion in 1965 and has been directly involved in instigating violence in the valley since 1989. The 1999 Kargil crisis is an extension of a similar strategy. Pakistan has adopted a dual strategy in Kashmir. It applies the option of a military offensive that increasingly relies on low intensity conflict now. Simultaneously, if the situation dictates, recourse to bilateral diplomacy that talks of negotiated settlement of the issue, is applied. Such a strategy is evident throughout the history that has defined Pakistan’s approach on Kashmir. Pakistan has also ensured that bilateral negotiation on Kashmir fails. This is because while Pakistan talks of discussing the ‘core issue’ it has not given up its traditional stand on Kashmir. This approach has limited the scope of bilateral negotiation where both the countries reiterate their traditional positions. Though the 1965 war was fought to capture Kashmir, Salman Taseer, Bhutto’s biographer wrote that Bhutto was aware that by invoking an armed uprising in Kashmir, when there was no large-scale unrest among the Kashmiris, Pakistan faced a full-fledged invasion across the international border in 1965. He maintains that this was done because he believed that his plan would be successful in mobilising international opinion against Indian control of the valley. 19 However, the Tashkent Declaration with the Soviet facilitation did not help Pakistan much. The word ‘Kashmir’ was not even mentioned in the Tashkent Declaration. The issue was subsumed under a broad category of bilateral disputes between India and Pakistan.

The 1971 war and creation of Bangladesh exposed Pakistan’s vulnerability as a nation state. The Simla Agreement put the Kashmir problem to a bilateral parameter further restraining the scope of internationalisation of the issue. Also, due to domestic political problems, Pakistan did not want an active involvement for the time in instigating trouble in the valley. After the separation of East Pakistan, Pakistan army became a highly demoralised group, thus military solution to the Kashmir issue for the time being was discarded as a policy. Speaking in the Pakistan’s National Assembly after the Simla Agreement, Bhutto said, “There is only one way to ‘get’ Kashmir- neither by negotiation nor through the United Nations. If you want the people of Kashmir to secure the right of self-determination they must fight for their right of self-determination. There is no other method. Twenty-five years of history has shown us that the right of self-determination cannot be achieved by proxy . . . . If the people of Jammu Kashmir want their independence, if they want freedom, if they want to be free people living in fraternity and friendship and comradeship with Pakistan, they will have to give the lead . . . . We will be with them”. 20 Discarding military solution to the Kashmir issue as an unviable proposition, Bhutto said, “The gain by war is that we have established for the moment, at least militarily, India has an upper hand. If we have gained nothing by peaceful means, we have certainly not gained by war.” 21

Bhutto’s policy in the aftermath of Shimla led to tenous peace. With domestic discontent rising against Bhutto’s regime, the political prophecy regarding the primacy of Kashmiris in resolving the Kashmir issue gave way to rhetorics. Bhutto’s commitment to Simla Agreement was questionable. According to a Western scholar, Bhutto’s commitment to Simla Agreement was not above suspicion. “What Bhutto had, in fact, agreed to at Simla was, to his mind, irrelevant as far as Kashmir was concerned: he had not accepted Indira Gandhi’s position, no matter what was written on the piece of paper he may have signed. He was realist enough to understand how weak Pakistan was, how tiny, how lacking in power for the moment. He never doubted that Pakistan would rise again some day to reclaim Kashmir, as he always believed it would do, for Kashmir was a Muslim state, after all, and thus ‘belonged’ by definition, to Pakistan. No agreement could change that ‘reality’, which was firmly rooted in the labyrinth of Zulfi Bhutto’s brain”. 22

Throughout the 1980s Pakistan was engaged as a frontline state of the United States to fight the Soviets. The close ties between India and the Soviet Union made Pakistan perceive the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan as an extension of the Indian threat. Pakistan could not have afforded to have hostile relations with India while it was facing the Soviet threat in the North-West Frontier area. Moreover, Pakistan’s involvement in Afghanistan opened up more opportunities for it to strengthen its defence preparedness with the aid of the Americans. Zia’s cricket diplomacy and playing a proactive role in the subcontinental peace-making assumed significance in the geo-political context. The death of Gen Zia and restoration of democracy in Pakistan coincided with the turbulence in the valley.

The problem with Pakistan is that it could not leave the solution of the Kashmir issue to the Kashmiris themselves. One of the reasons is that Pakistan sees a role for itself in the Kashmir problem. Secondly, Pakistan is not sure about entrusting the solution of the issue on the Kashmiris because it would not accept any solution that is not favourable to it. Though the façade of bilateral diplomacy was pursued till the late 1980s, Pakistan waited for an opportune moment. The changing geo-political situation in the late 1980s and the internal political developments in Kashmir provided Pakistan with a historic opportunity to pursue its Kashmir policy on its own terms i.e., providing material support and training and using some of the militant groups to pursue its foreign policy objectives in Kashmir. Thus, with the changing political developments, Pakistan’s Kashmir policy changed accordingly.

Explaining Pakistan’s stand on the Kashmir issue, the then Minister of State for Science and Technology Javed Jabbar said, “Kashmir is an issue, a concept, a principle, that is as fundamental to Pakistan as Pakistan itself. The very creation of the issue is linked with the creation of Pakistan . . . . Kashmir poses a single biggest challenge for the foreign policy of the Government of Pakistan, bigger, perhaps, even than Afghanistan . . . Pakistan faces the great and enormous challenge of re-prioritising Kashmir after a gap of 40 years.” 23 Syed Abida Hussain speaking on a debate on the Kashmir issue said, “The story of Kashmir is an endemic part of the story of the genesis of Pakistan . . . We were denied Kashmir and we entered, therefore the comity of nations as a State which had enormous vulnerability”. 24 Such articulations were more pronounced in Pakistani policy postures throughout the 1990s.

Perception of India: Invoking a Fear of Unreasonable Power

Pakistan’s stand on Kashmir and its approach to the solution have been derived through widespread and well-crafted publicity about the perceived Indian intention. The image of India in Pakistan has been profiled in such a manner that legitimacy to the Pakistan Army’s India policy is obtained automatically. To quote Ayub Khan, “India particularly has a deep pathological hatred for Muslims and her hostility to Pakistan stems from her refusal to see a Muslim power developing next door. By the same token, India will never tolerate a Muslim grouping near or far from her border.” 25

The Pakistani political elites have sustained an idea of a ‘hegemonic India’ by giving various references. For instance, some of the post-partition statements made by a few Indian leaders regarding the viability of the Pakistani state are interpreted as India’s intention to undo partition. India’s role in the creation of Bangladesh is portrayed as one such instance. Kashmir’s accession to India is interpreted as the latter not having accepted partition, which is often confused with the non-acceptance of the two-nation theory. Thus the image of India as an unreasonable power is nurtured by the political elites for their own institutional interests. Though fostering good neighbourly relations with India is underlined, the ideological differences are emphasised. Pakistan’s emphasis on socio-cultural differences to nurture its ideology itself is a setback to the bilateral ties. According to President Ayub Khan “Indian nationalism is based on Hinduism and Pakistan’s nationalism is based on Islam. The two philosophies are fundamentally different from each other. These two nationalisms cannot combine, but it should be possible for them to live side by side in peace and understanding. This is our foreign policy objective towards India.” 26 The hardliners interpret good neighbourly relations with India as equal to thousand years of slavery to the Indians. 27 Nevertheless, good neighbourliness is emphasised though later this got linked to the solution of Kashmir issue. Such kind of formulations have not only invoked a sense of mistrust about India but also have retarded generation of goodwill to strengthen confidence in bilateral relations. Moreover, the cultivated policy of portraying India as an unreasonable power has created a kind of perception where many Pakistanis feel that a ‘fair solution’ to the Kashmir issue cannot be expected. This provides the government with legitimacy to pursue policy options other than negotiation with India.

Bilateralism: Pakistan’s Perception

An image of India’s unreasonableness has been built up on the basis of non-implementation of the UN resolutions, not wanting to deal with the Kashmir and the Siachen issues. Pakistan’s role in all these problems is not mentioned. To add to this, the media has also provided a one-sided picture of human rights violation. In a country like Pakistan where expressing opinions other than representing the establishment view are restrained due to the military’s pre-eminence in politics, such kind of views are hardly questioned. Moreover, the general public hardly has any access to alternative sources of information other than the one provided by the government. Therefore, for the survival of the regime ‘anti-Indianism’ is adopted. An opinion is built up on this basis that Pakistan has no option but to seek international intervention since fair deal from India cannot be expected. This kind of opinion is so pervasive that some sections in Pakistan often question the possibility of solutions to various problems through bilateral negotiations. In addition to these, the propaganda regarding ‘India occupying Kashmir’ and ‘repression in Kashmir’ has negated any effort in resolving the issue. These issues are raised over and over again to portray India as an unreasonable power.

Given the background of the image that is portrayed of India, legitimacy to Pakistan’s policy is derived from a well-cultivated public opinion. Moreover, restrictions on people to people contact and lack of interaction has strengthened the negative image of India. This to a large extent explains Pakistan’s reluctance to engage positively with India. Further, Pakistan’s Kashmir-centric approach has been a major hindrance to bilateralism. Some Pakistani analysts feel that before talks on Kashmir are initiated between both the countries, Pakistan needs to allay its fears of Indian hegemony and India’s intentions. Suspicion regarding Indian intentions has made the elites of Pakistan to argue against bilateralism to resolve the Kashmir issue. As a Pakistani commentator wrote, Pakistan could neither negotiate nor expect fair deal from India. 28

The belief in the militants’ ability in garnering policy dividends on the Kashmir issue led many Pakistani analysts to argue against bilateral efforts. For instance, an editorial in The Nation cautioned the government, “There should be no move on the part of Islamabad which could be implied as casting the Kashmir issue to limbo for the sake of amity with India.” 29 Another analyst says, “Islamabad should avoid any process of dialogue which gives the impression of any bonhomie when outstanding issues remain unresolved.” 30 It is believed that normalisation of relations cannot happen unless Kashmir issue is resolved or progress is made. One of the reasons for the Kashmir-centric approach is Pakistan’s belief that through low intensity conflict it has gained an upper hand thus it is now the opportune time to resolve the conflict. The underlying conviction is that at least for the time being Pakistan has the capability to derail any resolution that would not be favourable to Pakistan. Thus, some Pakistanis even believe that the set back to the Lahore process happened because the Kashmir issue was not adequately or substantially addressed in the Memorandum of Understanding signed between the two countries.

There are some commentators who are against any kind of rapprochement with India, 31 because there is a feeling that there can be no substantive progress unless the Kashmir issue is addressed by India. 32 Since “the bottom line of the whole issue, according to official sources, is that such a dialogue can only harm the foreign policy interest of Pakistan.” 33 Thus while selling peace package, according to some Pakistani analysts, the government should be aware of ‘India’s intention’. 34

The bilateral talk between India and Pakistan is interpreted as ‘Indian trap’. A Pakistani commentator wrote that Pakistan should prepare for trilateral talks on Kashmir involving the leaders from both the parts of Kashmir and allow ‘freedom movement’ in Kashmir. At the same time it should devise methods to implement the UN resolution and should not talk to India unless the dispute is ‘justly and equitably solved’. 35 In this context the question arises how would Pakistan execute its foreign policy objectives in Kashmir by derailing bilateral efforts? It needs to be underlined here that it is not that bilateral dialogue per se cannot resolve the Kashmir issue but it is certainly clear to the Pakistani policy-makers that a Pakistani defined solution cannot be achieved within the parameter of bilateralism. Disagreeing on the uni-dimensional approach to Indo-Pak relations, Benazir Bhutto, in her article in The New York Times observed, “As the former Prime Minister of Pakistan, I observe events in Kashmir with keen interest. Indeed, one of my principal regrets is that my policies actually fed the tensions. Then, I believed that holding Indian-Pakistani relations hostage to the single issue of Kashmir would highlight the cause of the Kashmiri people. That policy certainly did not advance the cause of peace in South Asia”. 36

Interestingly, though many Pakistanis are aware of the complex character of the Kashmir issue and its domestic implications, the policy that has been followed by the political elite has not undergone any change. Pakistan’s stance on Kashmir and the popular belief that ‘Kashmir banega Pakistan’ made a commentator write, “It has been assumed that Kashmir is so sacred a cause that for its sake Pakistan can ignore its economic interests and suppress its domestic institution. . . . Every government has known that an armed conflict with India will not solve problem. The issue is, yet all of them have based their approach to the Kashmir problem and their defence strategy on the inevitability of war with India . . . ”. 37

Engaging in Low Intensity Conflict

Engaging in low intensity conflict is not a new concept in the Pakistani military vocabulary. Not to the extent that Pakistan has been engaged in after 1989 and the success it has extracted from this engagement in the form of cross-border terrorism. The present Pakistani involvement in Kashmir is attributed to the plan General Zia envisaged under the code name ‘Operation Topaz’. This has been a part of Pakistani strategy, firstly, due to the imbalance in their conventional weapon capability and secondly, due to the international public opinion against war as a mode of solution to the issue. Though both in 1948 and 1965 the strategy was to evoke a popular resentment, after 1989 Pakistan took advantage of popular discontent in the valley and provided material support and training to push its agenda in Kashmir. Even Bhutto knew the political advantage that Pakistan would have by being engaged in this kind of military strategy. For instance, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in a top-secret memo to Tikka Khan advocated people’s war against India to achieve Pakistan’s Kashmir policy objectives. He said, “In the new war the enemies around us will be depending largely upon material superiority and not human factor, upon technique and not force of an ideal. In this can lie their weakness and our strength . . . Recent history has amply proved, in China, in Korea, in Israel and in Vietnam that a people’s war can withstand innumerable ups and downs but that no force can succeed in altering its general march towards inevitable triumph . . . . And we ourselves have ruled them for eight centuries. All these are not ancient history.” 38 Bhutto was aware of the role Pakistan could play in gaining foreign policy objectives in Kashmir by an indirect involvement. While speaking in the Pakistan National Assembly in the context of the creation of Bangladesh he said, “No secessionist movement can ever succeed internally without external support. Modern governments, modern machinery is so poised, is so powerful that it cannot allow internal succession to succeed without foreign intervention.” 39 By engaging jihadis in the low intensily conflict with logistical support has enabled Pakistan to deny its involvement and at the same time reference to the issue of cross-border terrorism as ‘freedom struggle’ has given the required cushioning to the army-driven policy.

An Indian analyst wrote that terrorism in Kashmir is a tool to capture Kashmir through infiltration across the LoC. 40 The military option for the retrieval of Kashmir is always an alternative for the Pakistani political elites who argue on this line. As an analyst wrote, “The terrain in Kashmir is highly suitable for guerilla warfare. The six divisions of Indian army could be destroyed by the Kashmir people with minimal assistance by neighbouring countries . . . another (army) exercise must be held to train the army to fight decisive battles in Kashmir”. 41 A Pakistani commentator said that Pakistan’s policy is determined by its claim over the whole of Kashmir, and its commitment to enforcing it by any means, including the military, has resulted in the consequent state of armed confrontation with India. 42

Many people in Pakistan believe that the Sino-Indian war of 1962 had provided the best opportunity for Pakistan to retrieve Kashmir. Had Ayub Khan withstood American pressure, Pakistan would have got the rare chance of solving the Kashmir issue by military action. 43 According to a Pakistani commentator “The last serious attempt made by Pakistan to ‘settle’ the Kashmir issue was in 1965 and then too the military operation was not probably thought through, having been conceived and executed in isolation from the people of Kashmir, the people of Pakistan and international opinion”. 44 All these views attest that military solution to the Kashmir issue is considered a viable option by a section of the elite in Pakistan.

Low intensity conflict is not only advocated due to the conventional weapon disparity of Pakistan, but a thrust on military solution is based on perceived racial and martial superiority of the Muslim population. Such perception is kept alive in popular psyche to strengthen the military machinery of Pakistan at the cost of socio-economic development. To quote Hasan Zaheer, a former Cabinet Secretary, the 1965 ceasefire was believed by many Pakistanis ‘as a victory that was deprived’ by Ayub Khan. During the 1971 war, private vehicles, even public transport had stickers advocating ‘crush India’ and the slogan of ten Indians equal to one Pakistani not only caught the Pakistani imagination but also the professional soldiers who ought to have known better. 45 An instance of such estimation of Pakistan’s strength vis-à-vis India can be obtained from Henry Kissinger’s biography. Kissinger during his visit to Pakistan in 1970, asked whether Pakistan could win a war with India. In response Yahya Khan and his colleagues stated that there was a historic superiority of Muslim fighters. 46 Such assessment of strength has percolated down to popular belief regarding the martial superiority of Pakistanis. With a cocktail of historic Mughal rule, superiority of the Muslims has not only been a dream but a conviction for many Pakistanis who believe in a military solution. That is one of the reasons why many of the Pakistani analysts believe that Pakistan should provide moral, material and diplomatic support to sustain the Kashmir movement for a very long time. 47

Pakistan’s thrust on a military solution to the issue whether in the guise of tribal invasion or providing support to the militants, reflects Pakistan’s mindset with regard to the issue of Kashmir and how it perceives the solution of the issue. Bilateral negotiation is adopted in the event of international pressure. Even after the conclusion of the Simla Agreement, Pakistan never believed that the issue could be resolved bilaterally given the fact that it would not be easy for Pakistan to give up its traditional stand on which the regime’s survival depends. The position of Pakistan on the Kashmir issue itself defeats the very purpose of a negotiated settlement where it considers compromise as conceding an ideological ground to the other. Former COAS Jehangir Karamat says, “It is extremely difficult for the army to concede a position of military advantage-a position that the army believes it currently enjoys in Kashmir-for diplomatic gains that may lie sometime in the future”. 48

Internationalising the Kashmir Issue

Over a period of time Pakistan has been emphasising for third party mediation by arguing that bilateral negotiation has failed to resolve the issue. Its articulation on Kashmir issue in various international fora also suggests lack of commitment on its part to resolve the issue bilaterally. The policy posture, which mostly aims at maligning India, does not talk of concrete solution other than reiterating its traditional position. Pakistan’s strategy is summed up in the words of Lt. Gen. K.M.Arif, “To keep the issue alive, Kashmir must hit the headlines in the press and electronics media in the West . . . . My suggestion is that we should project India as a usurper of human rights . . . . India should be portrayed as an occupation force, a country which is holding Kashmiris against their will. We should portray India hurting minorities. Kashmiris are suffering because they happen to be Muslims in a Hindu state”. 49 In the aftermath of 1998 nuclear tests Pakistan has linked the Kashmir dispute to a nuclear flash point to attract the attention of the world to stress the need for the indulgence of the international community to resolve the problem, though this was implicitly done before the overt nuclearisation.

Implications of Kashmir Policy for the Pakistani Society

Though many Pakistani analysts feel that Pakistan’s involvement in the low intensity conflict in Kashmir by providing material support has paid political dividends, the domestic implications of such a policy have not received much attention from the Pakistani scholars and the media. In this context it is imperative to analyse what has been the domestic cost of such a policy. Would Pakistan sustain such a domestic cost to achieve its foreign policy objectives in Kashmir? If not, what are the options before it?

Growing Radicalism: Sectarian Violence

Jihad has become a well organised industry employing the poor and unemployed. To the unemployed youth, it gives employment and to the Islamist it gives a new meaning to life-sacrifice of self for the cause of Muslim Ummah. To the Government of Pakistan it becomes a subservient instrument in achieving foreign policy objectives, and to the army it provides uninterrupted supply of committed soldiers who would accomplish military objectives without many implications to the country’s security with very little investment. To the religious parties it gives a support base and provides them with a political aspiration to turn this into votes and from marginalised existence they have become forerunners in executing Pakistan’s foreign policy. Moreover, it has made the religious parties politically relevant. The vested interests of each of these organs have sustained militancy in Kashmir to the detriment of the interest of the Kashmiris. Most of the militants fighting in Kashmir according to a Western analyst are, “based in Pakistan, trained in Afghanistan, and motivated by pan-Islamic fundamentalism rather than Kashmiri nationalism. Their ranks filled with Punjabis and Pushtuns, Afghans and Arabs, many of the fighters wage war on behalf of a people whose language they do not even speak”. 50

In the north of Lahore, organisations like Markaz Dawa wal Irshad (Centre for Preaching) work to propagate an austere, ‘purified’ version of Islam, and set up schools across the country for this purpose. Its militant wing, the Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT, army of the pure), is an organisation of highly trained militants who are willing to go to war wherever and whenever the Amir (commander) orders. 51 They employ poor, illiterate Pakistanis to constitute an army of dedicated jihadis. This is a group that has been involved in suicidal attacks in Kashmir along with Jaish-e-Mohammad. This growing radicalism for the cause of Kashmir has severe implications for the Pakistani society. Organisations of every hue propagating jihad and commitment to fight in Kashmir have been given official patronage. Some of these organisations have been involved in sectarian violence in the name of religion in Pakistan. Criticising Pakistan government’s role in the growth of religious radicalism, a Pakistani analyst wrote, “In order to win over Kashmir, it has created blind hatred for India and tremendous support for war and military. The analysis of school and other texts by a number of researchers shows that the social sciences taught to students are meant to make them anti-India, anti-Hindu militant chauvinists. The result is that we have a large number of students from poor socio-economic background who are extremely militant and religious”. 52 Thus, Kashmir policy of Pakistan has created such an internal situation which threatens the ethnic and religious harmony in Pakistan. Threat to Pakistan arises from within rather than from India. 53

Militarisation of Pakistan Society: Spread of Small Arms

Militarisation of Pakistani society is a direct result of Pakistan’s involvement in a jihadi policy both in Kashmir and Afghanistan. As a side effect of the Afghan war and continuing violence in Kashmir, the tribal areas of Pakistan have become weapons bazaars where pistols, rifles, automatic weapons, grenades, mines and explosive are available freely. 54 To deal with the growing violence internally, Pakistan initiated in early 2001, a de-weaponisation campaign to flush out illegal arms, which have found their way into the Pakistani society. The monthly Herald quoting senior government officials wrote, the de-weaponisation campaign was sabotaged by the ISI which feared that this campaign would affect the jihadi organisation in Pakistan fighting in Kashmir. 55 The increase in violence in the Pakistani society has a direct correlation with the militancy in Kashmir. Violence has compounded since 1989. Many of the measures taken by the Pakistan government have either been half-heartedly implemented or ignored because such measures would directly impinge on Pakistan’s Kashmir policy. The de-weaponisation campaigns undertaken during Zia’s regime, Benazir’s regime and later Nawaz Sharif’s regime were not successful. 56 However, though measures taken by Gen Musharraf can be regarded as limited success compared to other regimes, the measures were taken more due to domestic compulsions with precautionary efforts that it should not impinge on the intensity of the Kashmir struggle. There has been criticism regarding the implementation of the de-weaponisation programme. Since the weapon industries are still making profits this itself suggests the failure of this campaign. Darra Adam Khel in the North West Frontier is also the main source of weapon supply to the Kashmiri militants who get special discount in the name of Jihad. 57 Apart from this, various militant organisations have their own sources of weapons, either supplied by the Pakistani intelligence agency or smuggled to the country with the connivance of the establishment. Domestic harmony would be largely dependent on Pakistan’s approach to jihad in particular and Kashmir in general.

Weakening of Democratic Institutions

The emphasis on a unidimensional Kashmir policy has resulted in growing tensions with India. Pakistan while pursuing the path of diplomacy has simultaneously abetted violence in Kashmir. As a result, it is the military that has been pursuing the foreign policy objective in Kashmir by executing and sustaining a low intensity conflict. Moreover, the perceived existence of an Indian threat and non-resolution of the Kashmir conflict has given justification to high defence expenditure. This has not only increased and strengthened the role of the military in politics but the religious parties have also been co-opted to help in the execution of these foreign policy objectives. The religious groups have provided necessary cadre and motivation to people who are fighting in Kashmir. Finally, the unidimensional focus on Kashmir has resulted in frequent military rule in addition to other factors. 58 As an analyst points out, the Pakistani army “had begun to develop their own views on reorganization and stabilization of Pakistan.” 59

The role of the ISI in executing Pakistan’s Kashmir policy has been enormous. Since the Kashmir policy has always remained a domain of the military, the ISI has been a frontrunner in marginalising the foreign office. At one point of time the ISI under Gen Imtiaz and Gen Nassir, “were making their own foreign policy as they went along and as it pleased them”. 60 The role of military has eroded the political legitimacy of popularly elected governments in Pakistan to engage in sustained political negotiation with India to resolve the Kashmir issue.

It would be difficult for Pakistan to sustain its Kashmir policy at the cost of implications to the internal situation. The post-September 11 scenario would restrain Pakistan even if it is prepared to afford the domestic costs. A lot would depend on Pakistan’s approach to clean its society from these fundamentalist elements. Cautioning radical groups, Gen Musharraf in his January 12 speech said, “The extreme minority must realize that Pakistan is not responsible for waging armed jihad in the world.” While delinking Pakistan’s role in waging jihad, he reiterated the traditional position of Pakistan. “Kashmir runs in our blood. No Pakistani can afford to sever links with Kashmir . . . . We will continue to extend our moral, political and diplomatic support to Kashmiris. We will never budge an inch from our principled stand on Kashmir.” Analysis of this posture raises doubt about negotiated settlement of the Kashmir issue which Pakistan publicly upholds. The posture is also ambiguous since at the same time Gen Musharraf underlines the need to resolve the issue by “dialogue and peaceful means in accordance with the wishes of the Kashmiri people and the UN resolutions”. 61 It is important to emphasise here that there is no mention of either the Simla Agreement or the Lahore Declaration in the speech. Though he cautioned, “No organisation will be allowed to indulge in terrorism in the name of Kashmir,” the underlying fact behind such an articulation according to Gen Musharraf’s interpretation is whatever is happening in Kashmir is a ‘freedom struggle’ rather than terrorism. Such playing with semantics would not see much change of the situation on the ground in Kashmir. In this context, his commitment to such an articulation remains to be seen since many of the organisations either changed their name or went underground after he banned Lashkar and Jaish. 62 As Herald reported, crackdown on the home front, “was a significant development nonetheless, one that suggested roundabout acknowledgement of the tacit or direct involvement of these groups in activities that could not be described as part and parcel of the Kashmir struggle.” 63

An analysis of Pakistan’s perception would make the policy posture it has adopted clear since its articulation is based on certain fundamental beliefs. Some of the beliefs have evolved through well-crafted articulation over a period of time. This itself is supported by manufactured public opinion that supports Pakistan’s policy.

Pakistan’s postulations are based on the following assumptions:-

1. Pakistan realises the UN resolution is not implementable because Pakistan would not like to withdraw from occupied Kashmir. But it talks of the UN resolution only to gain moral high ground, because Pakistan knows that India would not agree for a plebiscite. That saves Pakistan from implementing Clause-II of the resolution. Thus, it is a safe bet to talk of the UN resolution and appear to be a genuine protector of the interest of the Kashmiri Muslims. There exists an opinion in Pakistan that it is safe to talk of the UN resolution though many people realise that it is not implementable. 64

2. Pakistan’s articulation never mentions Clause II of the UN resolution i.e., withdrawal of troops from the parts that Pakistan had occupied through tribal invasion of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir, for a UN-led plebiscite to take place. Thus, many people in Pakistan talk of the self-determination clause of the UN resolution in isolation rather than in its entirety.

3. Many Pakistanis believe that in the event of self-determination it is most likely that Kashmir would opt for Pakistan since the UN resolution gives only two options to the Kashmiris.

4. Grievances of the Kashmiris are interpreted as a favourable opinion of the Kashmiris towards Pakistan which would lead them to vote for Pakistan in the event of self-determination.

5. Pakistan has lately successfully portrayed that it is the valley which is disputed and since it has a Muslim majority population it should, by the logic of the two-nation theory, belong to Pakistan. Pakistan has postured this as a compromise formula. This would also give Pakistan an opportunity to wriggle out of the Clause-II of the UN resolution. This is because many in Pakistan believe that the issue of Pakistan-Occupied-Kashmir is a settled issue by the logic of the two-nation theory. 65 The Indian posture has generated such a belief since India’s claim on Pakistan-Occupied-Kashmir is limited to official bilateral dialogue only.

6. On the whole, Pakistan has made it appear that only the part of Kashmir which is with India is a disputed territory and India is retaining the state of Jammu and Kashmir and particularly the Kashmir valley only by force.

Options for India

1. The projection of Kashmir in India has been defensive. This is because, the democratic polity of India, with its free press, makes the people aware about the misadministration in Kashmir that prompted large scale dissatisfaction in the Valley. This deflects the focus on Pakistan’s role in fomenting trouble. Thus, India’s projection of the root cause of problems in Kashmir needs to be broadened.

2. In the whole dispute, the part of Kashmir that is with Pakistan has hardly got much emphasis in comparison to the Pakistani articulation in the valley. The world has very little knowledge about the nature of administration in the part of Kashmir that is under Pakistan’s occupation thus making it appear that everything is fine in the Pakistan-Occupied-Kashmir. India’s approach should therefore be tuned accordingly.

3. India needs to articulate more on the reason why plebiscite could not be implemented i.e., Pakistan’s refusal to implement the second clause of the UN resolution. Moreover, the cultural and ethnic character of the part of Kashmir under Pakistan’s occupation has not been maintained since there is no barrier for any Pakistani to migrate and settle whereas India through article 370 has maintained the ethnic character of Kashmir. In these circumstances how can a UN plebiscite be held in Kashmir, since after fifty-four years, it is difficult to distinguish between a Pakistani and a Kashmiri in the POK?

4. The facade of ‘Azad’ Kashmir should be exposed. Having a title like Prime Minister or President does not make the state independent. The people of Pakistan-Occupied-Kashmir are dissatisfied with misadministration and under-development.

The Changing Scenario and Kashmir

In the changing scenario of the post-September 11 political developments, Pakistan’s overt support to militants in Kashmir cannot continue with impunity. The emerging situation also indicates that Afghanistan cannot be used as a training ground for the foreign militants who were exported to Kashmir earlier to engage the Indian army. As reported, some of the training camps that were functioning in Punjab have been shifted to the Pakistan-Occupied-Kashmir. However, the supply of jihadis to fight in Kashmir is not going see any reduction since there would not be any dearth of jihadis due to poor socio-economic conditions. Moreover, religious indoctrination would provide motivation to many people to join in the name of jihad. Pakistan’s decision to join the US-led alliance has disillusioned the jihadis and Pakistan’s commitment to the Kashmir issue is being doubted. The militant organisations based in Pakistan and operating in Kashmir are likely to be discreet now in their operation. The military is reluctant to give up the perceived ‘upper hand’ in the Kashmir problem. Moreover, it would be difficult to cut the umbilical cord between the jihadis and the military establishment since these groups are nurtured by the establishment. That is the reason why both January 12 and May 27 speeches of President Musharraf were percieved with a lot of skepticism. Many countries including India have made it clear that the General would be believed if the situation on the ground improves.

Given the emerging situation, the factor which assumes significance is what would be the solution to the Kashmir issue from a Pakistani perspective. Interestingly, many Pakistanis put forward a confederal solution to the Kashmir issue. According to a Pakistani analyst, “A confederal set-up with a joint commission comprising six Kashmiri representatives plus three each from India and Pakistan, forming a higher governing body and looking after all affairs (of united Kashmir) except for defence and foreign affairs, which would be the responsibility of another joint Indo-Pak committee in Delhi and Islamabad . . . The Indian and Pakistani members could be nominated by their respective countries while the Kashmiri members of the commission could be elected. Under this higher Kashmir body, would be an elected Provincial/State Assembly along with a cabinet and a chief minister. A governor could be nominated alternatively by India and Pakistan for a two-year period each term”. 66 Since many people believe that only the valley is disputed this kind of propositions are mentioned as a win-win formula. This poses a problem for the Indian policy-makers.

The question that arises here is what could be a solution given the reality of nuclear weapons and the posture adopted by both the countries. The problem lies in the perception of both the countries. India’s argument is based on Maharaja Hari Singh’s accession, which legally entitles India to Kashmir, and Pakistan’s claim is based on the two-nation theory. This makes Kashmir a zero-sum game.

The only viable solution could be dividing Kashmir along the line of control. This is suggested by many political leaders who have a stake in the solution. According to Farooq Abdullah, “Neither is India going to leave this part, nor is Pakistan going to leave that part. Whether we have hundred wars or a thousand wars, it is just not going to happen. We are just going to bleed each other dry”. 67 According to Benazir Bhutto, the solution to the Kashmir issue could be as in the case of Israel and Jordan. According to her:-

“The two sections of Kashmir should have open and porous borders. Both sections would be demilitarized and patrolled by either an international peacekeeping force or a joint Indian-Pakistani peacekeeping force. Both legislative councils would continue to meet separately and on occasion jointly. The people on both sides of divided Kashmir could meet and interact freely and informally. None of these steps would prejudice or prejudge the position of both countries on the disputed areas. Simultaneously, the borders between Pakistan and its South Asian neighbours, including India, would be opened for unrestricted trade, cultural cooperation and exchange. Tariffs and quotas between the nations would be eliminated. Educational and technological exchanges at the secondary and university levels would be initiated on a broad scale. Discussions would commence on the creation of a South Asian Free Market Zone, which would expand unrestricted and untaxed trade to include India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan and the Maldives-a free-market zone modeled after the European Community and the North American Free-Trade Agreement. Only after all of these confidence-building mechanisms were in place, and only after a significant set period of time (Camp David called for a five-year transition), would the parties commence discussions on a formal and final resolution to the Kashmir problem, based on the wishes of its people and the security concerns of both India and Pakistan.”

Movement of people across the Line of Control was also favoured by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. Elaborating on his view, Rafi Raza writes that Bhutto maintained that only by normalising relations there could be increased exchanges between both the countries and later within Kashmir, and with the passage of time Cease-fire Line or Line of Control becomes irrelevant. Later speaking to Kuldip Nayyar on March 27, 1972, Bhutto said, “We can make the Cease-fire Line as the basis of initial peace. Let the people of Kashmir move between the two countries freely. One thing can lead to another . . . . We cannot clear the deck in one sweep”. 68 Given the reality of the military situation after the nuclear tests there is a growing belief that LoC as an international border is a viable option though many people do not want to talk publicly regarding this issue given the Government of Pakistan’s Kashmir policy. 69

Recently, the Kashmir Advisory Committee has been formed to look into the Kashmir policy of Pakistan. Mushahid Hussain, who is a member of this committee, wrote in The Nation, “The Kashmir struggle, which has entered a crucial phase, will now need to give primacy to its political face and indigenous character, with a more innovative and active strategy required to achieve the goal of self-determination . . . Given this context, the challenge before Pakistan is to sustain its Kashmir policy with a creative approach aimed at seeking a change in the status quo, which in any case, has been rejected by the Kashmiri people”. 70 While advising the Government of Pakistan, Mushahid Hussain wrote, not to repeat the mistake of Afghan policy by pursuing only the favourite groups, Pakistan’s endeavour should be to keep the unity of the All Party Hurriyat Conference (APHC), keeping diverse opinions on the Kashmir issue intact with the bottom line of rejecting the status quo. While pursuing this policy Pakistan should not adopt any policy that it cannot sustain and should not ask for third party mediation. Pakistan should relentlessly reaffirm UN resolutions and self-determination and focus on human rights violation in the valley. 71 However, subscribing to this opinion would be playing the zero sum game again and would be an untenable policy given the dwindling local support to militancy and an urge for normalcy in the valley.

Challenges Ahead

Over the period of time the Kashmir problem has sustained various groups who have vested interest in the continuation of the problem. Some of the militants engaged in violence in Kashmir have well-defined economic interests. The criminalisation of the struggle has taken place to such an extent that many people opt to fight in Kashmir for money. 72 So much so, after the death of a person fighting in Kashmir, the responsibility of the associated family becomes the concern of the recruiting group. 73 Nowhere in the world do any recruiting agencies offer this kind of benefits. In a country like Pakistan where unemployment and growing population have become a major concern, such facilities, though with risk, are attractive, more so, due to lack of alternative sources of employment. According to a report, Pakistan has the largest private army of Islamists. 74

The Kashmir issue has given political relevance to many splinter political groups, religious organisations and militant outfits. From obscure existence, these groups have made political capital out of it and have managed to get extensive coverage in the media portraying them as messiah. Had the ‘issue’ not been there, these groups would have had marginalised existence. These groups would challenge any solution that would sideline them in the future political set up. Moreover, “With easy foreign funding flowing unregulated, these armed mercenaries are not hindered by rules and regulations. While foreign countries have their own agenda for funding, activities of such a growing number of fundamentalists are difficult to regulate”. 75 This would pose a challenge to peace in Kashmir.

Pakistan’s aspiration to confine the Indo-Pak dialogue to Kashmir only reflects its narrow approach and is against both the spirit of the Simla Agreement and the the Lahore Declaration. Pakistan has always portrayed Kashmir as an unsettled issue. It has questioned the instrument of accession and has kept the desire for independence of the Kashmiris alive in the event the UN resolution is not implemented. Moreover, the independent Kashmir option is articulated carefully to get the valley separated from India first, then ultimately to merge it with Pakistan. While manipulating the sentiments regarding independent Kashmir, various interest groups have kept the issue alive for various reasons. Some of the reasons are: since such a proposition would not be acceptable to India, the zero sum game can be played for a longer time, which would sustain the insurgency that has become an industry. This would also provide the Pakistan army with a dominant role in the domestic politics and they would continue with unquestionable defence allocations. Often the Kashmiris themselves and some Indian analysts refer to the unique culture of Kashmir. There are talks of Kashmiriyat and their sense of identity and independence is invoked to portray that they are different from the other parts of India. If reference to history is made, every parts of India has its own historic identity and cultural diversity. Though the religion may be broadly Hinduism and their beliefs and rituals are also diverse, the fact of uniqueness can be applied to each region of the country. However, the historical sense of independence and uniqueness cannot be justified for creation of independent entities at present. The question to ponder over is that a Muslim majority state is talking of alienation and incompatibility whereas the minorities are cohabiting with other religious groups in different parts of India. Thus, there exists a political reason to the identity factor rather than cultural one. This has been sustained and propagated to argue for independence by some Kashmiri groups.

Interpreting Kashmir as a zero sum game, a Pakistani analyst commented that Kashmir would continue to be exploited by the leaders of both the countries for nationalistic interest. 76 The issue of Kashmir is likely to remain alive for many decades due to the diametrically opposite arguments put forward by both the countries. Though Pakistan has been talking of holding discussion on Kashmir in a free and fair manner ‘anytime anywhere’ it is not clear whether Pakistan would talks of any new approach. Unless there is harmonisation of position, another round of talk would not yield anything but would lead to reiteration of the old stands. The underlining fact is, Pakistan would continue to pursue its foreign policy objective through low intensity conflict as long as it can afford it with an army-dominated decision-making apparatus. 77 The question arises here, can Pakistan achieve domestic stability by pursuing a jhadi policy vis-à-vis India in Kashmir though Pakistan cannot afford the domestic implications of the growing radicalism? Jihad needs to be delinked from Pakistan’s Kashmir policy because Pakistan cannot achieve domestic stability and deal with sectarian violence while encouraging jihad in Kashmir. This is so because Jihad cannot have different meanings in domestic and international context. As it appears, the Line of Control should be the ideal solution with an open border, given the reality of the situation. Pakistan would need to educate its public. The problem in accepting such a solution arises from the fact that India giving up its claim over the Pakistan Occupied-Kashmir is not considered as a compromise in Pakistan due to lack of public articulation on the subject. According to a retired career diplomat, Kashmir issue “has been built up to the extent that I cannot see any leadership in Pakistan diluting the focus on it. In private conversations you might hear words like ‘compromise’, ‘give and take’, ‘via media’, but in publicly declared policy or in public statements it is tantamount to political suicide. Indeed it is not unrealistic that any leader in Pakistan who genuinely tries to break this deadlock will need the courage of, and be prepared to meet the same fate as, a Sadat or a Rabin”. 78 Since Pakistan for the past 54 years has generated public opinion in favour of its policy, it would be difficult to change its posture swiftly. The only way Pakistan can wriggle out of the situation of its own creation without adverse public opinion is to allow the democratic process in Kashmir to take root. It should encourage the Hurriyat Conference to participate in the election. At the same time it should stop the infiltration to ensure peace in the state. This will allow both Pakistan and India to compromise along the LoC with free movement of the Kashmiris across the border. Otherwise, by reiterating the traditional stand on Kashmir without compromise and hoping for solution would be farfetched from reality. With the growth of radicalism in both the countries, even this solution would be difficult with the passage of time. The question is, whether Pakistan can have a Kashmir policy that would be sustainable and implementable without domestic costs. Clearly, and in the light of this, Pakistan needs a reappraisal of its Kashmir policy.

Endnotes

Note *: Dr. Smruti S. Pattanaik, a Research Officer at IDSA, has a PhD from Jawaharlal Nehru University. She did her doctoral work at the South Asian Studies Division of the School of International Studies of the University. She specialises on security issues pertaining to the South Asia region. Back.

Note 1: Panderel Moon (Ed) The Transfer of Power 1942-47, vol XII, HMSO; London, n.d. pp.348-51. Back.

Note 2: Air Marshal Ayaz Ahmad Khan, India-Pakistan Relations, Frontier Post. Peshawar. September 8, 2000. Back.

Note 3: Latif Ahmed Sherwani, Kashmir Accession to India. Pakistan Horizon April 1990, 43(2), 54. Back.

Note 4: Ibid., p.28. Also see the White Paper on Jammu and Kashmir presented to the National Assembly of Pakistan in 1977 reproduced in the Frontier Post. In the first part of the White Paper that appeared on April 3, 1990 it is mentioned that Maharaja Hari Singh prevented the natural accession of the state to Pakistan. It also mentioned that all of Kashmir’s communication following the direction of its river led into Pakistan and there was no link with India. The Frontier Post. April 3, 1990. Back.

Note 5: Hasan-Askari Rizvi, The Military and Politics in Pakistan 1947-86 1987. Progressive Publishers; Lahore. p. 39. Back.

Note 6: For such a view refer to Ayub Khan, Friend not Master 1967. Oxford University Press; London. p. 124. Back.

Note 7: Sardar Abdul Qayyum Khan, Kashmir Problem an Appraisal. In Tariq Jan and Ghulam Sarwar Ed., Kashmir Problem: Challenge and Response, 1990. Institute for Policy Studies; Islamabad. p. 67. Back.

Note 8: Ayub Khan, no. 6, p. 114. Back.

Note 9: Ayub Khan, no. 6, p. 123. Back.

Note 10: As cited in Ajit Bhattacharjea, Z.A.Bhutto’s Double Speak: Turning Defeat into Victory. The Times of India. New Delhi. May 3, 1995. Back.

Note 11: Iqbal Akhund, Advisor to the PM on Foreign Affairs and National Security on “National Security and Pakistan’s Foreign Policy in a Changing World” in his address to Pakistan Institute for International Affairs on April 5, 1990. See National Security and Pakistan’s Foreign Policy. Pakistan Horizon. April 1990 43(2) . Back.

Note 12: Akbar Khan, Raiders in Kashmir, n.d. Army Publishers; Delhi. p. 10. Back.

Note 13: The Muslim. Islamabad. October 18, 1989. Back.

Note 14: The Nation. Islamabad. September 19, 1989. Back.

Note 15: Stephen Cohen, The Pakistan Army 1998. Oxford University Press; Karachi. p. 173. Back.

Note 16: Editorial, Newsline. July 1999. p.13. Back.

Note 18: White Paper on the Jammu and Kashmir Dispute: Mediation by the UN (1948-53), The Frontier Post. April 5, 1990. Back.

Note 19: As quoted in M.H.Askari, The Dawn. Karachi. 18 April 1991. Back.

Note 20: See Pakistan National Assembly Debates. 2(5) July 14, 1974, p. 713. Back.

Note 22: Stanley Wolpert, Zulfi Bhutto of Pakistan 1998. Oxford University Press; Karachi. p. 192. Back.

Note 23: Pakistan National Assembly Debates, 1(1), February 5, 1990, pp. 61-62. Back.

Note 25: Ayub, no. 6, p.183. Also see Air Marshal Ayaz Ahmad Khan, India-Pakistan Relations. Frontier Post. September 8, 2000. Back.

Note 26: Ayub, no. 6, p. 128. Back.

Note 27: For the controversial text of anti-government pamphlet as published in urdu weekly Takbeer, see Public Opinion Trend (Pakistan Series) 17(189), October 9, 1989, pp. 3682-87. Back.

Note 28: E.A.S. Bokhari, Indo-Pak Mismatch in Weapon and Missiles, The Nation. January 20, 1989. Back.

Note 29: The Nation. Editorial. Message from Srinagar. April 7, 1991. However there was a definite indication for Pakistan to continue the dialogue. See M.H. Askari, Dialogue Should Continue. The Dawn. April 10, 1991, Hasan Askari Rizvi, Pakistan-India Diplomacy. The Nation. April 3, 1991. Back.

Note 30: Maleeha Lodhi, New Low in Indo-Pak Relations. The News. Rawalpindi. December 18, 1992. Back.

Note 31: Shirin Mazari wrote that such an attitude can be described as a desperate desire among some of the decision-makers in Pakistan. Some of the elite even invite Indian film stars for fund raising. Describing this as a policy of appeasement she wrote that there should be reciprocal approach and should not be done at the cost of national interest. The Muslim. April 23, 1991. Back.

Note 32: The News Editorial August 12, 1991. Back.

Note 33: As cited in the The Times of India. February 27, 1995. Back.

Note 34: The Nation. Editorial September 17, 1991. Back.

Note 35: Air Marshal Ayaz Ahmed Khan, India Played its Card Well in Islamabad Talks. The Muslim. January 15, 1994. Back.

Note 36: Benazir Bhutto, Camp David for Kashmir. The New York Times. June 8, 1999 Back.

Note 37: I.A.Rehman, Hope of Deliverance. Newsline. January 1995. Back.

Note 38: Prime Minister Z.A.Bhutto to the Chief of Army Staff, June 23, 1973, as cited in Wolpert, no. 22, p. 186. Back.

Note 39: See Pakistan National Assembly Debates. 2(5) July 14, 1974, p. 695. Back.

Note 40: G.C. Katoch, War or Peace. The Hindustan Times. New Delhi. September 27, 1990. Pakistan will not give up its support for terrorism unless the cost is too high. Refer Manoj Joshi, Is there a Shared Interest in Promoting Peace. Hindu. Madras. June 19, 1990. K.Subhramanyam talks of containment rather than an approach of war with Pakistan. See, Dealing with Pakistan: Containment Better than War. Times of India. June 26, 1990. War no option. See, KD Majumdar, India and Pakistan: No Dividend in Hostilities. Statesman. Calcutta. June 27, 1990. Times of India Editorial A Necessary Dialogue. July 21, 1990. Back.

Note 41: Air Marshal (retd) Ayaz Ahmad Khan, Pakistan Times. Islamabad. September 30, 1989. Back.

Note 42: Hasan Zaheer, Rawalpindi Conspiracy 1951, 1998, Oxford University Press; Karachi. p. xix. Back.

Note 43: Hamid Yusuf, Pakistan: A Study of Political Developments 1947-97 1999. Sang-e-Meel Publications; Lahore. p. 91. Back.

Note 44: Mushahid Hussain, Choices Before Pakistan on Kashmir. The Nation. February 4, 1990. Back.

Note 45: Though the 1971 war resulted in the separation of East Pakistan, the thrust was to teach India a lesson for its involvement in the East Pakistan crisis. Refer Hasan Zaheer, The Separation of East Pakistan: The Rise and Realisation of Bengali Muslim Nationalism. 1995. Oxford University Press; New York. p. 358. Back.

Note 46: Henry Kissinger, My White House Years. 1979. Vikas Publishing House; Delhi. p.861. Back.

Note 47: See S.M.Qureshi, Kashmir Liberation Struggle and our Foreign Policy: Some Recommendation, In Tariq Jan and Ghulam Sarwar eds., no. 7, p. 83. Back.

Note 48: Aamer Ahmad Khan, The End of Jihad. The Herald, December 2001, p. 21. Back.

Note 49: Gen K.M. Arif, Kashmir Problem-Overview. In Tariq Jan and Ghulam Sarwar (Eds.), no. 7, p. 65. Back.

Note 50: Jonah Blank, Kashmir: Fundamentalism Takes Root. Foreign Affairs. November/December 1999, p. 42. Back.

Note 51: Zaigham Khan, Allah’s Army. The Herald. January 1998, p.124. The sole purpose of this organisation is to impart military training. It is also reported that all the arms inside the Dawa secretariat are licensed. Aamer Ahmad Khan, The Wrong End of the Stick. The Herald. December 1995, p.38 Back.