|

|

|

|

Korea: better social policies for a stronger economy

by Willem Adema, Peter Tergeist and Raymond Torres Directorate for Education, Employment, Labour and Social Affairs

Crisis, what crisis, is a tempting way to describe Korea these days. With the economy expanding rapidly again and unemployment below 4%, which is low by most standards, the traumatic effects of the financial crisis of late 1997 are receding in many people's memories.

As a result, it may be easy to assume that the crisis was just an unpleasant blip in an otherwise strong growth path. But that would be a highly optimistic view. In truth, the social pillar on which Korean development leans is still fragile, and this carries serious economic risks. To paraphrase President Kim Dae-Jung, "it is not yet the time to open the bottle of champagne".

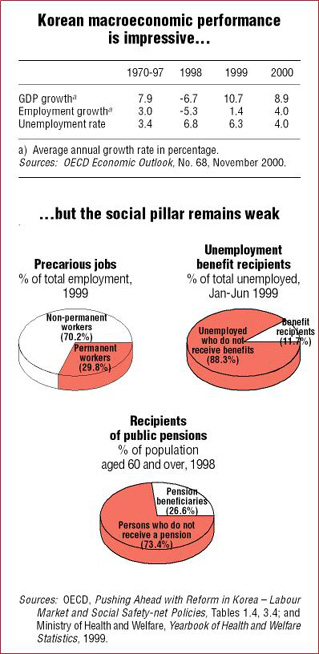

Take jobs for instance. Despite double-digit rates of growth, most jobs are extremely precarious. In 1999, less than 30% of workers had a permanent (i.e open-ended) contract. In fact, Korea has the lowest number of workers holding a permanent job in the OECD, followed by Turkey. On the other hand, because so many contracts are fixed-term or even daily, the majority of Korean workers face considerable job precariousness, while only a relatively small number of workers enjoy stable employment situations.

Despite recent reforms, such as the introduction of public works and the expansion of social assistance programmes, the social safety net still has too many holes, leaving large segments of the population unprotected. For example, only one in nine of the unemployed receives unemployment benefits. In addition, benefits are rather modest for the limited number of unemployed workers who receive them, amounting to 50% of the previous wage, while the maximum duration of benefit receipt ranges from three to eight months. Worrying for those reaching the end of their entitlement is that social assistance programmes are inadequate and pay out benefits that are below the poverty line. What's more, nearly half of those living in poverty receive no social assistance benefits at all, due to stringent eligibility criteria.

Another problem is the immaturity of the public pension system, which benefits only a quarter of people at retirement age. Moreover, the average pension currently amounts to two-thirds of the minimum wage, or a meagre US$3-4 a day, while recently introduced special allowances for poor elderly persons amount to less than a dollar a day.

Hardly helping matters is the fact that Korea's social partners don't trust each other. During the crisis, trade unions and employers agreed on an important economic and social reform programme, including measures to strengthen the social safety net, enhance labour market flexibility and moderate wage increases in a bid to stem the rise in unemployment. But with the return of rapid growth and falling unemployment, old confrontational attitudes have re-surfaced. Arresting and imprisoning workers for what might be considered legitimate trade union practices is back in vogue, a matter of considerable concern both at the OECD and the International Labour Organisation (ILO). The arrests are not only a threat to the exercise of fundamental workers' rights, they also hamper the development of trust that is so essential to successful industrial relations. This makes it extremely difficult for the social partners to agree on basic aims, like wage moderation, and improving employment conditions and workforce practices.

The poor social climate does not help to improve productivity either, which in Korea is something of an Achilles' heel. In fact, growth in the 1990s was largely driven by capital investment, but overall productivity practically stagnated. Many of the investment projects carried out in the 1990s were unproductive, a key factor behind the 1997 crisis. To remedy this chink in Korea's economic edifice requires, among other things, the provision of more and better training (which experience shows goes hand-in-hand with improving job tenure) and a more efficient social safety net. In other words, policymakers cannot afford to underestimate the link that exists between the social and the economic dimension, since to do so would increase the risk of another crisis taking place.

Better Programmes

In the past two years, the government has considerably expanded the range of labour market programmes. Yet, some basic weaknesses have to be resolved. In particular, small firms often do not pay social contributions; this has to be corrected to ensure that their workers are entitled to unemployment and public pension benefits. Moreover, active labour market programmes should be designed to reach the really needy, which is not happening, despite the large number of programmes. Indeed, given the brisk recovery, there is a strong case for scaling back public works programmes, while enhancing training programmes to upgrade the skills of specific categories of workers.

Already, public employment services have been greatly expanded in order to help the unemployed move back into the labour market. The quality of counselling will prove important in this regard, and more staff training may be needed. The government should do what it can to maximise the reach of these services too. One way of doing this would be for their employment offices to take advantage of the extensive network of private employment agencies in Korea, including contracting out some services to them.

Improving social protection would eventually open the way for some enterprise-based benefits, such as retirement and separation allowances, to be scaled back; these enterprise benefits mainly accrue to permanent workers and therefore make employers reluctant to convert fixed-term and daily contracts into permanent ones.

In October 2000 a newly reformed social assistance system comes into effect. The new system is based on the concept of "productive welfare" and a balancing of rights and responsibilities on the part of social assistance recipients. First, anyone who is eligible for social assistance should receive it as a right and the level of benefits will increase. Despite these efforts, reflecting complex eligibility rules, many individuals living in poverty will either receive very low benefits or, in certain cases, no benefits at all.

Second, in exchange for assistance, beneficiaries who are able to work will be obliged to search for jobs and to accept training, public works jobs and any job placements provided by the local welfare office, with the objective to promote self-reliance.

Moreover, the government has hired additional social welfare officers, but it is unclear whether these officers will have the means (or indeed expertise) to help recipients find a job. Overall, despite the problems, the new law is a step in the right direction.

Handled well, the October measures hold some promise. The question is how to fund them. For a start, the government could consider raising taxes - at just over 20% of GDP, the tax burden is light by OECD standards. However, before going down that thorny political road, it could find some money by channelling funds away from other programmes, such as public works. And it could look for savings by ensuring that its programmes are properly evaluated with a view to leaning resources towards the most cost-effective ones.

Towards International Standards

When Korea negotiated its accession to the OECD in 1995-96, its laws on labour and industrial relations reflected the legacy of authoritarian political regimes and were out of line with internationally-accepted standards. The Korean government at that point made a commitment to reform its labour laws, and ensure fundamental rights such as freedom of association and collective bargaining. Since 1996, legislative reforms have indeed brought Korean labour law closer to international norms. Nevertheless, further reform is needed in several areas.

Take trade union pluralism, for instance. Up until a few years ago, one national trade union organisation, the FKTU, enjoyed a virtual monopoly as the representative of employee interests. This did not conform to fundamental ILO Conventions on freedom of association and collective bargaining. In 1997, Korea modified its legislation to recognise the principle of trade union pluralism, thus allowing the formation and recognition of rival trade union centres, in particular the KCTU. By contrast, the law still prohibits (until 2002) the existence of multiple unions at company level.

Another problem is that unemployed or dismissed workers are not permitted to join trade unions. Clearly, behind this legislation is the fear of infiltration by outside radicals, although the concept of enterprise unionism, where bargaining is carried out mainly by the actors at company level, also plays a role. Still, in practically all other OECD countries the preconditions for union membership are determined by the trade unions themselves.

There are additional problems with labour regulations in the public sector. Only in 1999 were public (and private) school teachers awarded freedom-of-association and collective bargaining rights, and public officials were given the right to form consultative workplace associations. These were laudable steps, but Korea has to go further and allow trade unions with bargaining rights to be freely set up in the public service (even if, as in other countries, the legal status of wage agreements for public officials may differ from that of private sector employees).

As in some other OECD countries, strikes in central and local government are prohibited in Korea. However, by requiring compulsory arbitration, Korean law virtually prohibits all industrial action in "essential services", whose unusually broad definition includes the likes of banks, transportation and oil supply. Korea is under international pressure to narrow this definition - as it has already started to do - and should consider alternatives to an overall strike ban, such as the maintenance of "skeleton" services.

The OECD will conduct a follow-up study of labour market and social safety-net policies in Korea in 2002. This will be an opportunity to review whether the trend towards job precariousness has been reversed, holes in the social safety net have been filled and labour law reforms have continued. With the current signs of rapprochement between the two parts of the country, the need for the government in Seoul to get its economic and social policies right will become all the more pressing. END

* This article summarises the findings of a larger study produced jointly with Jaehung Lee and Elena Stancanelli:

OECD, Pushing Ahead with Reform in Korea: Labour Market and Social Safety-net Policies, Paris, 2000.