|

|

|

|

Alternative futures AD 2000-2025

by Walter C. Clemens JR., Professor of political science at Boston University

Of the many potential scenarios, global governance looks the most fruitful.

We start with three facts of world affairs. The first is the interdependence of states their mutual vulnerability in many domains. Second is globalisation the many forces that transcend state borders from epidemics to electronic banking. Third is the pyramid of power military, economic, political, cultural. At the onset of the 21st century the world is unipolar. It combines a single superpower with successive levels of great, medium, regional, and rising powers.

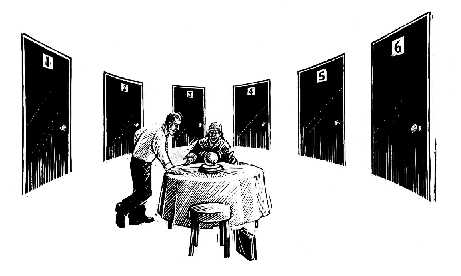

SIX SCENARIOS

Many alternative futures are conceivable but let us focus on six. We portray each scenario as a fact not what could, would, or should be. The first scenario proceeds from the present pyramid of power.

I. UNIPOLAR STABILITY

US hegemony is rooted in tangible and intangible assets that show no sign of weakening. The unipolar world continues for decades. It proves to be the most peaceful and prosperous era in human history. It is a world in which most states deal with global interdependence so as to generate mutual gain. International actors focus more on creating values for mutual gain than on aggressive exploitation or parasitism. The model the Canadian-Mexican-US relationship than, say, to the triangle of India, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan. Unipolarity proves to be more conducive to peace than multilateral balancing or bipolarity. It does not, however, prevent disorder among lesser states and failing states. Outside powers, usually with UN blessing, intervene in some but not all trouble spots.

The United States is a new kind of hegemon on the world stage. A deal takes shape: Washington does not abuse its power and other countries do not gang up against it. The sole superpower seldom acts alone. Washington seeks and usually gets the support of other actors for its key goals, as it did in forging a policy to contain Iraq and North Korea in the 1990s.

Economic prospects for most of the world are positive. The world is sufficiently rich and well informed to find paths to sustainable development. The World Bank formulates guidelines by which countries can enlarge their GDP and improve their Human Development Index ratings. Infant mortality continues to decline in most countries. Russia begins to realise its economic potential. New giants arise China, Brazil, Argentina, Indonesia, Kazakstan. But none of these countries has the wish or the means to challenge the global hegemon.

Europe and Japan remain powerful trading states. Europe, however, is at most a confederation. Real union is unfeasible due to language, cultural, and economic differences. Alliance with America remains the linchpin of Japans security. The country faces severe limits. Its archipelago remains crowded. The population becomes greyer with fewer workers to support retirees. Japans foreign markets shrink as Korea and other neighbours fill the same demands at lower prices.

Authoritarian rule curtails the once vibrant growth of Singapore and Hong Kong. Most Pacific rim economies slow their torrid pace as fresh inputs of labour, capital, and energy become more costly.

II. FRAGMENTED CHAOS

Extrapolations from the relative calm and prosperity of the late 20th century may miss the mark. How could chaos replace stability? A serious change in any part of the system can ripple throughout the whole. First, the biosphere fails to support human life in some places where it flourished in the 1990s. The affluent Pacific rim sits on a ring of fire volcanoes and fault lines that devour life and property. Storms and droughts increase due to climate change and deforestation. Both environmental and economic barriers impede growth. It is easier to call for sustainable development than to practice it. Epidemics such as H.I.V. infection undermine both physical and financial health.

Second, the rational calm inspired by expanding prosperity is not shared by actors whose deep demands go unmet. Unemployed youth in many countries resent the gap between haves and havenots. Religious and ethnic zealots incite violence. Some states fail.

Third, weapons of mass destruction become more accessible. A single nuclear explosion near a city set off by mechanical accident, human error, or design makes Chernobyl and Oklahoma City look like childs play. Reports that Iraq is ready to launch anthrax-filled warheads create panic in Iran and Israel.

When the awakening giant China trembles, there are global repercussions. Millions are unemployed as the economy slows. Malthus strikes: China has sacrificed too much farm land to industry. Border peoples become more restive. Authoritarian rule is challenged by democratic reformers and regional potentates. Transitions from dictatorship can endanger world peace.

The United States fails to lead or throws its weight too aggressively. It antagonizes followers or loses them. Washington oscillates between do-nothing complacency and hubristic arrogance of power. The US home front deteriorates as racial and class cleavages multiply; as Hispanic and other groups reject the long dominant culture; as guns rule some streets and many schools; and as Congress and the public refuse to invest in science, public health, or infrastructure.

As many countries follow the US lead, their democracy suffers from brain washing by mass media technology. Couch potato fast-food obesity and drug dependency impede brain power and physical health. Parasitism also takes its toll. Many actors try to free-load. While more and more individuals bowl alone some of them lost in cyberspace a global time of troubles engulfs humanity.

III. CHALLENGE TO THE HEGEMON

Nothing lasts. When Uncle Sam appears weak or overbearing, rising powers challenge the hegemon. Most Chinese remain poor, but the countrys enormous GDP permits Beijing to build formidable armed forces. Chinas engineers move the country to the leading edge of technology. Chinas oil requirements deepen its motives to hold onto Central Asia and to dominate the South China Sea.

Problems multiply when China cracks down harder on its Uygurs, Kazakhs, and Tibetans; insists that Japan stop building antimissile defences; and demands that Taiwan join in a Beijing-dominated federation. Washington again sends aircraft carriers to the Taiwan Straits. The danger to peace is far greater than when an Austrian archduke died in Sarajevo.

Here the road forks. One direction sees China back down before the US show of force. Like Russias rulers in 1911 and 1962, however, Beijing swears never again to retreat before rival power. China steps up military investments and prepares for a confrontation one or two decades hence.

The other fork also leads to trouble: Washington pulls back while Beijing incorporates Taiwan into China. The PRC then bullies other neighbours Vietnam, Korea, Japan, Russia, India. Washington wants to contain China, but blows hot and cold. Emboldened, China marches toward a collision with the enfeebled hegemon, believing it will win the next round.

IV. BIPOLAR CO-OPERATION

China and the United States have equivalent GDPs by 2025. Their economies are more complementary than competitive. Beijing and Washington have no territorial claims on each other. Co-operative projects convince their peoples that mutual gain is possible in all fields.

The Taiwan issue no longer troubles PRC-US relations. China adapts the Taiwan model as technocrats supplant ideologists in Beijing. Mainland China and Taiwan are linked economically but distinct politically. They agree to disagree on politics.

China keeps to its late 20th century borders and focuses on internal problems. China suffers many severe economic and environmental challenges but other countries give or sell food and other goods to fill deficits. China is not active at the United Nations but rarely objects to peacemaking by others.

V. MULTIPOLAR CO-OPERATION

The poles of power are diverse but complementary. Democracy and peace reinforce each other. Most governments are representative democracies, linked by trade and other collaborative ventures. Cyberspace joins scientists, cultural figures, business people, relatives, and e-mail pals across the world.

Even before 2025 Moscow and Washington cut their nuclear arsenals to 600 strategic warheads. Other nuclear powers keep their arsenals well below this number. The military requirements set out in Articles 43-47 of the UN Charter are fulfilled. The UN Security Council has a Military Staff Committee; and most UN members have earmarked forces for use by the Security Council. Collective security is becoming a reality. The tough action taken by the UN against Saddam Hussein in the 1990s encourages confidence in collective security and discourages rogue attacks on the evolving world order. Israel and most of its neighbours are learning how to co-exist and trade.

North-South differences narrow. More Asian, African, Middle Eastern, and Latin American countries enter the path of rapid and sustainable development. New strains of wheat, rice, maize, and other crops permit nearly every region to feed itself without heavy irrigation or chemicals. Few countries still depend on a single commodity. Both developing and industrialised countries shift resources from defence to development needs. Biodiversity in the Amazon and other tropical regions is protected and becomes profitable.

VI. GLOBAL GOVERNANCE WITHOUT WORLD GOVERNMENT

The transnational civil society develops across many countries and regions. Common values political choice, trust in free markets, respect for human rights are shared by more than three-quarters of humanity. Territoriality weakens as a principle of organisation. There is no world government by a supranational authority. National governments remain, but they share power with a medley of non-governmental agencies business and labour groups as well as nongovernmental organisations (NGOs). Together they form expanding networks of institutions designed to meet a wide range of human needs.

National governments confer among themselves and with responsible specialists from international and transnational agencies. This is functionalism writ large decisionmaking informed and managed by experts, mediated and supervised by representatives of elected governments. To cope with epidemics, for example, government experts form a committee drawn from national medical boards, the World Health Organization, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and the recently formed International Academy of Health Sciences. To deal with economic problems from currency fluctuations to commodity prices government experts form a committee drawn from the OECD, World Bank, the IMF, leading commercial banks, and the recently formed International Academy of Economic and Social Scientists.

To deal with threats to peace and security, governments depend heavily on the UN Security Council and the UN Secretary-General. Some governments retain nuclear arsenals, but the Security Council has its own rapid reaction force, backed by designated units from most UN members. The UN Secretary-General has a panel of mediators whom she/he can propose to disputants. A committee of elders drawn from Nobel Peace Prize laureates advises the Security Council and the Secretary-General.

By 2005 the University of the Middle East, founded by Arabs and Israelis who met in US graduate schools, has received help from some governments and foundations. By 2025 it has trained a generation of men and women more concerned with peaceful development than with sectarian passions. By 2025 they have launched several projects that knit Israel and its neighbours in mutual gain.

World governance is global public policy responding to the dangers and opportunities inherent in globalisation.

WHICH SCENARIO IS BEST? WHICH IS MOST FEASIBLE?

It is easy to say which scenarios are the worst. Scenarios II and III could destroy many lives and waste valuable assets. Wise planners will act to block the roads that lead in these directions.

Any scenario that promotes peace and prosperity is acceptable. But scenario VI world governance has advantages. First, it postulates development of a truly transnational society. Without such a society, the state system may eventually break down.

Second, global governance cultivates a rich emergent structure in which NGOs and governments face complex challenges together. Such teamwork provides the flexibility and reach needed to deal with emerging needs.

Is learning possible before the roof crashes? A vision of international relations rooted in global interdependence provides a broader

framework than realism or idealism for planning the future. Actors may see that past practices do not suffice to deal with looming problems such as global warming. Even antagonists may find themselves condemned by interdependence to negotiate better solutions.

The concept of interdependence underlines both the dangers and the opportunities inherent in globalisation. As a guide to policy it does not presume that humans are good or bad. But it hopes that enlightened self-interest will guide governments and other actors to create values for mutual gain rather than try to seize them for one-sided advantage.