|

|

|

|

The OECD Observer

October/November 1998, No. 214

Redefining tertiary education

By Alan Wagner

Rising participation rates, diminishing labour market opportunities and intense competition for public and private funds have combined to put tertiary education policy under renewed pressure. Moreover, education at this level is increasingly led by demand, with institutions of all types having to adapt themselves to students’ requirements. Governments have to readjust their policies too. (Redefining Tertiary Education (http://www.oecd.org/scripts/publications/bookshop/redirect.asp?911998021P1), OECD Publications, Paris, 1998.)

Tertiary education is a key part of lifelong learning and a cornerstone of today’s knowledge society. It is also a broader notion than it used to be, incorporating most forms and levels of education beyond secondary schooling, and including both conventional university and non-university types of institutions and programmes. Tertiary education also means new kinds of institutions, work-based settings, distance learning and other arrangements. Unlike conventional definitions used by the OECD before, (Towards Mass Higher Education, OECD Publications, Paris, 1974; Universities Under Scrutiny, OECD Publications, Paris, 1987.) tertiary education now puts the focus as much on demand as it does on supply. In other words, it is more student-led than it was in the past, and that has new implications for stakeholders, institutions and resource planning.

Tertiary education is expanding

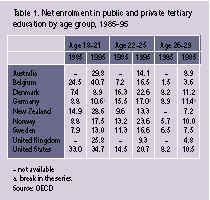

Tertiary education is where the pressures of growth and change are most acutely felt. As observed in each of the countries participating in the OECD’s current review of tertiary education, the challenges are several. They include how to accommodate students, mobilise staff and resources, devise curricula and teaching procedures, as well as meeting rising costs. And even though the growth in the level of tertiary participation in education has slowed in OECD countries since the start of the 1990s, the participation rate—which is the overall proportion of any post-school age group attending tertiary education—is rising (Table 1). In the United Kingdom, the participation rate of school leavers is slightly above 30%. But this figure fails to take into account the participation rate of mature students; if the latter is included, the probability of participation in tertiary education over a lifetime in the United Kingdom may be above 60%. (A. Smithers, P. Robinson, ‘Post-18 education: growth, change and prospects’, The Council for Industry and Higher Education, London, 1995.) The Australian education minister, David Kemp, said in a recent policy statement that the ‘probability of a current teenager entering some form of post-secondary education or training at some point in their life is near 90%’. This is a high estimate because it considers education over a lifetime and embraces a broad definition of post-secondary education. In Finland, a similar picture has emerged. When the OECD undertook a review of higher education there in 1994, the target participation rate was considered to be ambitiously high, at around 65%. But that figure has since been reached and the government expects the rate to rise further.

One conclusion from all this is that tertiary-level studies are no longer reserved for an exclusive minority. In fact, the trend seems to be towards universal participation. Learners at this level are more diverse in terms of their backgrounds, interests and career paths. The new challenge is how to adapt programmes to student demand, rather than the traditional approach of plugging students into programmes. This requires that the definition of standards be thought through properly; a practical approach would be to devise a range of standards and qualifications based on a common understanding of learning objectives. There are instructive examples of this in several countries: one is the former Higher Education Quality Council’s work in the United Kingdom on ‘graduateness’—a new notion which attempts to capture what each graduate should know and be able to do; reforms in the United States to strengthen the general education parts of degree programmes is another example.

Increased student diversity has affected an earlier tendency among different types of institutions to establish distinct missions and patterns of funding, governance and recruitment. The direction of change—as seen in countries such as Belgium (Flemish Community), Denmark and New Zealand—has been to introduce more diversity but less formal differentiation.

New strategic relationships are also emerging between different institutions to meet new demands, for example, in the United States, notably Virginia, with credit transfers between community colleges and degree institutions in the public and private sectors. The use of telecommunications-based distance learning tools have also spurred co-operation, such as between Blue Ridge Community College and Old Dominion University, via Teletechnet.

In New Zealand, recognition and linkages are improving between different educational institutions; secondary schools now offer tertiary-level modules which polytechnics and universities may accept and credit towards their qualifications. In Australia a few universities have absorbed within their institutional structures some technical and further education institutes (TAFE) which are not a formal part of the higher education system. There are also programmes being offered jointly by special training colleges and private universities in Japan.

In Denmark a policy review is underway as to the possibility of mergers between universities and those institutions running medium-cycle programmes, such as in teacher training, business and physiotherapy. Bringing short-cycle programmes, which tend to provide advanced courses in business fields, such as accounting, into the institutions offering medium-cycle programmes is also under discussion.

The role of private institutions in education is evolving and conventional private suppliers are finding themselves having to adjust to the new challenges in education too. Private involvement is already important in tertiary education in Japan, Korea, Portugal and the United States, and policies are being proposed to open up the field to private establishments in New Zealand and Australia.

Student demand is driving change

Many new pathways and combinations in education in OECD countries are the fruit not so much of deliberate policies, but rather of choices made by the students themselves. (Education Policy Analysis (http://www.oecd.org/scripts/publications/bookshop/redirect.asp?961997051P1), OECD Publications, Paris, 1997.) And such is the diversity of demand that students can no longer be easily distinguished according to programme enrolment. Full-time and part-time students, young and mature, fee paying or grant assisted—all are to be found working alongside each other in the same classrooms, laboratories, libraries and computing rooms throughout the OECD area. It is a trend which might be extended further. At their meeting in June 1998 OECD employment, labour and social affairs ministers drew attention to the importance of promoting a wider range of opportunities and activities for people as they get older (Table 2). Tertiary education features prominently in this vision. And while public, institutional and employer preferences and constraints remain important, the interests, backgrounds and demands of students are at the centre of thinking and planning.

There are several problems in tertiary education which demand attention. Pressure on resources, mainly because of tightening budgets, has resulted in a deterioration in staff-student ratios. Overcrowding is common in several OECD countries and the quality of teaching and learning is often quite uneven. New curriculum designs and educational strategies, for example, encouraging more distance learning, have only partly helped. But much is yet to be done, particularly in ensuring that education continues to progress to the full benefit of students and that the worlds of learning and work are brought closer together.

Finding ways of reducing the inefficiencies created by high drop-out rates and under-achievement is another pressing challenge, and is the focus of attention particularly at secondary level. But these problems are increasingly being addressed in tertiary education too. The responsibility for overcoming education failure may in general have to be shared widely. But at the tertiary level educational institutions have a particular responsibility towards helping to reduce the level of under-achievement. One possible way of doing this is to work more closely with schools as part of the drive to improve their flexibility and understanding of how students want to learn.

One emerging question is how to deal with the needs of those who remain outside of education as the participation rate rises. A positive strategy might be to find a place for everyone in tertiary education as a pro-active way of enhancing skills and knowledge, boosting life-chances and combating the costly waste generated by social exclusion. In practical terms, that may mean reviewing some of the conditions attached to certain types of welfare benefits so as not only to encourage participation in education, but to make sure that those who wish to study are not penalised in any way for doing so.

Deep-rooted reforms are needed

Reforms are being carried out in education, but progress has been mixed. The new bachelor’s degree in Denmark is an example of the new flexibility that may be required. Its purpose is to offer a tertiary qualification before the normal degree. It is recognised by employers and leaves open the possibility of returning to higher studies later on. Initiatives elsewhere are worth taking note of. The peer tutorat in France, in which advanced-level students work alongside new entrants, is one. Enhanced counselling in France and Belgium (Flemish Community) is another approach, wherein special teaching and counselling services are made available to first-year students. And learning centres in Belgium (Flemish Community), the United Kingdom and the United States which bring together library, laboratories and other student services are flexible in that they allow for independent, self-directed study even in constrained environments.

These new initiatives often complement or adapt current teaching and learning approaches. Deeper reforms may be needed, though. Building new links between work and study, as in France, the United Kingdom and the United States, is important. And further improvements in the transferability of academic credits from one institution to another, such as is possible in New Zealand, and in the recognition and transferability of credits between countries, would give extra momentum to student learning.

As the use of information and communication technology spreads, students will have a wider repertoire of learning sources to draw on. These opportunities will probably foster a more creative and critical approach to learning. Students will be able (and probably be expected) to exercise more choice and to pace their own learning. On the other hand, a mechanical use of available technology as a mere teaching aid would stifle creativity. So far in the OECD area generally, curricula, teaching and learning have not taken full advantage of the technologies now available.

The conventional idea of specific careers for specific types of education, while still valid in many jobs, is coming under increasing pressure. Not that we have too many graduates—if anything, we may have too few. But rather, tertiary education will have to become broader, encouraging more initiative and entrepreneurship, and a more flexible enthusiasm regarding work and lifelong learning.

Getting the resources

If, as is suggested in the OECD report, Redefining Tertiary Education, participation rates continue to expand, perhaps exceeding 75%, (Human Capital Investment—A Comparative Report (http://www.oecd.org/scripts/publications/bookshop/redirect.asp?961998021P1), OECD Publications, Paris, 1998.) then the question of resources will surely become the most pressing one of all. An argument for mobilising resources from stakeholders other than governments has been advanced in the OECD’s work on human capital investment. While tertiary education constitutes a relatively high cost to the taxpayer (on a per student basis), it appears to generate relatively high direct benefits to those who participate, in terms of subsequent employment and so on.

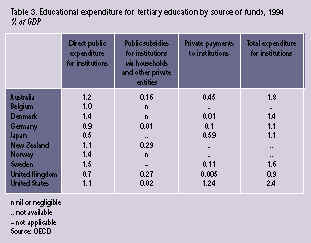

Spending on tertiary education by students and families has been growing in a number of OECD countries (Table 3). Fees or deferred charges are being either introduced or increased in several OECD countries, and student support schemes are being strengthened in others. However, there are worries about the possible future impacts of different loan schemes, for example, on patterns of domestic demand and there is a hesitancy in some countries about creating future debt obligations on today’s students.

Developing in young people the motivation and capacity for learning and giving them a bigger share of the responsibility for learning means changing the way society thinks about ‘teaching’, its physical infrastructure and technology supports. It demands striking the right balance between new approaches and the traditional modes of teaching and learning. But this implies more—and more effective—investment than is presently the case.

There may be arguments for increasing investment in tertiary education. But competing demands on resources require that any new investment in learning be undertaken with more attention to type, method and content. In other words, quality of education will be more important than quantity when it comes to working out returns on investment at the tertiary level. Moreover, the investment costs to enable learners to acquire qualifications would not only be diminished over the longer term, the costs would be shared more widely too.

Lifelong learning is important to the consolidation of the knowledge society and changes in tertiary education are therefore inevitable. The challenge is to manage those changes properly and to cater for the new and increased demands on education. Only then will it be possible to extend the opportunities in tertiary education to a much larger portion of each generation and at a manageable cost to the public budget.

OECD Bibliography

Redefining Tertiary Education, 1998

Human Capital Investment – A Comparative Report, 1998

Tom Healy, ‘Counting Human Capital’, The OECD Observer, No. 212, June/July 1998

(http://www.oecd.org/publications/observer/212/Article8_eng.htm)

Education Policy Analysis, 1997

Universities Under Scrutiny, 1987

Towards Mass Higher Education, 1974.

Alan Wagner: OECD Directorate for Education, Employment, Labour and Social Affairs