|

|

|

|

The OECD Observer

October/November 1998, No. 214

Y2K

By Vladimir López-Bassols

The article is based upon the findings of a pending study of OECD countries: “The Year 2000 Problem: Impacts and Actions ,” (http://www.oecd.org/puma/gvrnance/it/y2k.htm) carried out by the Public Management Service (PUMA) (http://www.oecd.org/puma/) and Directorate for Science Technology and Industry (DSTI) (http://www.oecd.org/dsti/sti/).

Y2K might sound like the name of a newly discovered planet. In fact, it is the short label for the year 2000 problem, otherwise called the Millennium Bug. Quite simply, most computer systems today were programmed to identify calendar dates using the last two digits of the year. The aim was to save memory. But many computers will not recognise 00 as 2000 when the clock ticks past midnight on December 31, 1999. As a result, it is likely that some programmes will fail or at least malfunction.

There could be all sorts of problems, whether in computer systems, communication networks, or in embedded chips integrated into industrial control systems and consumer electronics. Perhaps the worst scenario would be sudden failure in safety systems affecting health services, defence, nuclear energy generation and air travel, or in critical sectors such as utilities, financial services, telecommunications and government services. Even now, current systems which perform post-2000 forecasting or transactions have already begun to experience failures.

Y2K is a global problem which can be resolved through proper management and co-ordination by firms and governments alike. Most major companies seem to be taking corrective action, but there is concern about whether smaller companies have either the knowledge or the funds to follow suit. It is an expensive business: many firms are allocating up to two-thirds of their annual IT budgets over the next two years to solve the problem. It is also an uncertain one and even the insurance industry has not been able to assess the true scale of the risks of Y2K. Apart from the cost involved, there is also some uncertainty about whether there is enough personnel to go round. Certainly, salaries for some categories of consulting IT professionals have been rising rapidly, which indicates a shortage of supply, although high pay should quickly attract new engineers into the market.

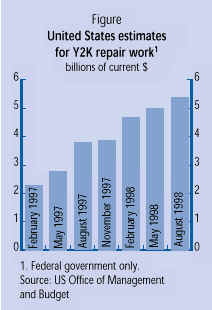

The economic effects of the Millennium Bug can be quantified in various ways: first the direct cost to governments and firms of resources diverted to fix non-compliant systems. Estimates of this cost at a world-wide level are in the $300-600 billion range (not including embedded systems), according to a study undertaken by the Gartner Group. The direct fixed costs will vary across industries, depending on the extent of their reliance on IT and network communications. Direct spending on achieving compliance could have positive short-term economic spin-offs, such as higher sales of software and increased employment for IT staff. The long-term outcome could include improved efficiency of information systems. Nevertheless, the negative impacts of Y2K are likely to cancel out the short-term benefits. This is because most of the expenditure on fixing Y2K will be related to fixing existing capital stock, rather than improving it. There are secondary costs too, which non-compliance of systems could generate: billing errors, delayed payrolls and tax collection, and potentially explosive insurance and litigation bills. All of this could prove very costly for government, and for intermediaries in financial services.

Analysts have finally begun to speculate on the possible macro-economic effects of the millennium bug. Widespread business disruptions would hurt investment spending in technology from this year until after 2000. And financial markets could react badly as the level of Y2K-related risk of firms and countries becomes more apparent, leading to falls in stock and increased bankruptcies. In Europe and other financial centres around the world, the development and conversion of software in connection with the new euro will largely be concurrent with Y2K work. There may even be short-term inflationary pressures from demand for new investment, supply-side disruptions, and wage increases of IT specialists. Productivity growth is likely to decline temporarily as resources are diverted to maintain the economy’s productive capacity.

Given the interdependence of economies and the potential for cross-border disruption from the year 2000, international initiatives are needed to co-ordinate remediation, testing and contingency planning, especially for developing countries where awareness of the issue remains low, and action is lagging. But governments could do more, for instance:

Other relevant sites:

Focus Online—Millennium countdown (http://www.oecd.org/puma/focus/current/y2k.htm)

Year 2000 Links (http://www.oecd.org/dsti/sti/it/infosoc/news/y2klinks.htm)

Realising the potential of global electronic commerce (http://www.oecd.org/publications/observer/214/Article6_eng.htm) (article is publised in the Observer issue No. 214 (October/November 1998)

The promise of 21st century technology (http://www.oecd.org/publications/observer/214/article7-eng.htm) (article is publised in the Observer issue No. 214 (October/November 1998)

The Year 2000 Problem: Impacts and Actions (http://www.oecd.org/puma/gvrnance/it/y2k.htm) (The report, co-ordinated by the OECD’s Public Management Service (PUMA), includes a review of economy-wide and sectoral impacts carried out by the Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry (DSTI), and a PUMA-written chapter on governments’ role and actions, based primarily on responses to a questionnaire received from countries in June and July.)

Vladimir López-Bassols: OECD Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry (DSTI)