|

|

|

|

The OECD Observer

October/November 1998, No. 214

Opening Pathways from Education to Work

By Marianne Durand-Drouhin, Phillip McKenzie, and Richard Sweet

The pathways linking full-time education and work can be long and complicated. The journey is an uncertain one, particularly for those young people who have struggled in education from an early age and expect to have little or no contact with tertiary education. Government policy in OECD countries has often concentrated on providing support to these groups after they have left school. Yet the evidence suggests that improving educational attainment would boost young people’s chances and at a lower cost to the public purse. (Education Policy Analysis, OECD Publications, Paris, forthcoming1998.)

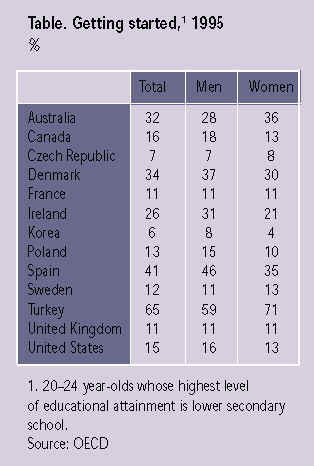

The participation rate in education has been rising in OECD countries in recent years. Yet, on average around a quarter of young people leave school without completing their upper-secondary education (Table). Intense competition in the labour market and the rising demand for skilled labour make it hard for them to find stable employment, often preventing their smooth integration to adult society. Policies to tackle this have tended to focus on the problems in the transition stage itself, though with mixed results.

Many of the obstacles young school-leavers face are caused by failure or under-achievement at school. Early school-leavers find it difficult to get work simply because they do not have the sound general education, information technology skills and foreign languages which most growth sectors require. This is particularly true of services, such as in health and information technology, where much employment is being created in OECD countries. And even in those expanding services where skills are not a priority, young job seekers can still be crowded out by over-qualified competitors.

How quickly young people find their first job after leaving school has a powerful effect on their employment and career prospects and a poor start in the labour market can be difficult to overcome. (Employment Outlook, OECD Publications, Paris, 1998, http://www.oecd.org/els/publicatio/labour/eoblurb.htm#Employment Outlook 1998 - Editorial.) Unqualified early school-leavers tend either to take up part-time or temporary jobs, or to become unemployed. Some leave the labour force altogether.

On the principle that prevention is better than cure, the pathways to work and adult life would be improved by aiming government policy first and foremost at reducing failure levels at school. (Overcoming Failure at School, OECD Publications, Paris, forthcoming 1998). That said, improving the success of education is clearly not enough, as the evidence for groups with and without full secondary education in different OECD countries shows.

Staying in Work

There are striking differences between the experiences of people with low levels of qualifications in different countries. Early school-leavers in Germany have more success in obtaining and keeping work in the first five years after leaving initial education than their counterparts in Australia, France, Ireland or the United States (Figure). The average job duration for the United States is the shortest, at 3.3 years employment for men and just 1.7 year for women. In each of these five countries people with higher qualifications are more likely to work in the years after leaving education than their less qualified counterparts. But between countries the rule does not appear to hold. For example, young German men who have dropped out of school early spend slightly longer in employment—an average of 4.4 years for their first five years out of school—than the 4.2 years spent at work by young Australian men who have completed their tertiary education.

A Question of Learning

A commonly cited reason for Germany’s strong performance is its apprenticeship system, from which young adults clearly benefit. Apprenticeships are also one of the reasons why youth employment in Germany is relatively low: it stood at 10% in 1997, compared with an OECD average of 13.4% and an EU average of 20.4%. Apprenticeship systems are also important in Austria, Denmark and Switzerland. Their success has prompted other countries to implement similar systems or to expand existing ones. Australia, Norway, the United Kingdom and the United States all have growing apprenticeship systems. But are apprenticeships the way forward for all OECD countries?

For a start, they are not easy to get right, and particular apprenticeship systems cannot simply be copied from one country to another. This is because a whole range of social, economic and political conditions have to be in place for apprenticeship systems to work. Employers have to be ready to co-operate in formal groups with public authorities to design and implement training regulations, courses and certification. Another condition appears to be the cultivation of a strong social partnership between governments, employers and trade unions to agree on wage levels and other training conditions. The downside of all this is that the process can be slow and sometimes rigid, since changes can only be implemented after a lengthy and exhaustive period of analysis, consultation and policy debate between the partners. That means that dedicated resources, in terms of both time and money, have to be made available.

Apprenticeship systems also raise questions of balance between initial and continued lifelong learning. In countries with extensive apprenticeship provision young people are tracked into at least two different education streams between the ages of 10 and 12. General and vocational pathways are often kept quite separate from each other at the upper secondary level and the connections between apprenticeship training and tertiary education remain limited. In a bid to improve the balance of learning some OECD countries, such as Australia and the United Kingdom, moved away from this two-streamed approach in the 1960s and ‘70s to develop comprehensive education instead, with an emphasis on conventional secondary courses. After that move the perception grew that vocational streams were inferior in quality to conventional education.

This view appears to be increasingly held in the traditional apprenticeship countries themselves. Countries like Austria and Germany now find that more and more young people want to register in general education instead of vocational and technical schools. Apprenticeship programmes are still strong, but are no longer as popular as they were, in part because difficult economic times and increasing competition have forced firms to become more reluctant to provide them. But the main reason would appear to be that, in contrast to full-time vocational and technical education, apprenticeships generally do not leave open the possibility of entering tertiary education at a later stage.

Double-qualifying Pathways

Traditional apprenticeship arrangements may not therefore hold the answer for all OECD countries seeking to reduce youth unemployment or to facilitate young people’s transition from education to work. A broader approach would be to create pathways which can meet both the demand for conventional tertiary education and the requirements of the job market. These double-qualifying pathways are in the development stage in a number of countries. They include many types of early contact with the labour market, from formal apprenticeships to internships and student projects. They enable students to see the worlds of work and study as intertwined and therefore create a positive attitude towards lifelong learning. And studies show that vocational approaches which can qualify young people for both work and tertiary-level study are attractive. (Pathways and Participation in Vocational and Technical Education and Training, OECD Publications, Paris, 1998, http://www.oecd.org/scripts/publications/bookshop/redirect.asp?911998011P1.)

Austria, for example, has been providing double qualifying vocational/technical pathways in its full-time schools (Berufliche Höhere Schulen, or BHS) for several years. These programmes are highly regarded by employers and provide access to tertiary education as well. The BHS curriculum includes obligatory summer internships, in which students are typically required to solve real problems in the firm. This pathway takes a year longer than the traditional four-year programmes of upper secondary education. But young Austrians tend to prefer it to standard vocational education and now more than 20% of young people take it at the end of compulsory schooling. The immediate employment prospects of the graduates from the BHS schools are at least as good as, and often better than, those of apprentices. In addition, because their occupational qualifications are of a stronger level and provide access to higher education, the BHS graduates are able to make better careers.

The community colleges of North America could have the same potential as the Austrian BHS, even though they cater for a wider spectrum of the population. The fact that they are open to all age groups makes them very flexible. They offer school leavers the opportunity to obtain occupational qualifications and, if they wish, to prepare for entry into higher education. Although the community colleges do not have the same formal structures for company involvement as the Austrian BHS, many have developed their own successful partnerships with industry at local and regional level.

Nordic Policy has Coherence...

Beyond specific organisational considerations, there is a wider issue of how to develop coherent education, labour and social policies for young people on preparing for work and adult life. The Nordic countries have come closest to asking that question and have spent two decades developing the youth guarantee approach, which provides an opportunity to all by way of a place in either education, training or work up to the age of 18 or 20. Every attempt is made to ensure that the places on offer are both useful and relevant. Though possible, it is difficult for unemployed young people to refuse an opportunity once it comes up and a system of incentives and penalties, with tight safety nets for those who fail, has helped this policy approach to work.

Although their institutional frameworks differ, the approaches in both the Nordic and the traditional apprenticeship countries have a lot in common. Both are based on the notion of social responsibility towards young people’s integration into work. They both depend on the active engagement of employers and trade unions in policy making, programme design and certification. Their broad principles strengthen social and economic policy generally, and rather than being specific to their country’s traditions and institutions, can be applied to many other OECD countries.

The Nordic approach highlights the importance of making a distinction between teenagers and young people over the age of 20, who are beyond the normal age of upper secondary education. The most appropriate way to help high-risk teenagers to make a successful transition to work and adult life may, in many cases, be to keep them in school (or apprenticeship) for a further year or two, to help them to return to school quickly, or to get them into post-school training as rapidly as possible. The measures required for the 20-24 age group are of a different kind. In this group achieving stable employment combined with providing skills training, are the priorities. For this, the age limits for apprenticeships and various educational programmes might have to be raised. And subsidies or tax relief might have to be considered for employers who provide training in the workplace. It is important to strike the right balance of incentives and penalties in welfare support to encourage members of this older age group to seek and take up employment and training.

... but is it the Answer?

Youth unemployment has not been eradicated in the Nordic countries. However, the number of very young people in the labour market has been considerably reduced, and strong partnerships have been developed between schools, local communities and businesses. The Norwegian and Swedish approaches can put a strain on municipal resources, particularly because of their emphasis on following-up young school leavers, identifying those who have failed to make a successful transition, and developing individual action plans for them. But the Nordic approach has the virtue of keeping the number of early school leavers down. Most of all, it shows that the chances of policy intervention working are higher while young people are still in school.

OECD Bibliography

Overcoming Failure at School, forthcoming 1998

Education Policy Analysis, forthcoming 1998

Employment Outlook, 1998

(http://www.oecd.org/els/publicatio/labour/eoblurb.htm#Employment Outlook 1998 - Editorial.)

‘The OECD Employment Outlook—Toward an Employment-centred Social Policy’, The OECD Observer, No. 213, August/September 1998

(http://www.oecd.org/publications/observer/213/fortherecord.htm)

Pathways and Participation in Vocational and Technical Education and Training, 1998.

Marianne Durand-Drouhin, Phillip McKenzie and Richard Sweet: OECD Directorate for Education, Employment, Labour and Social Affairs.