|

|

|

|

Journal of Military and Strategic Studies

Journal of Military and Strategic Studies

Canadian-U.S. Industry, Trade, and Cross-Border Commerce in Defense: The U.S. Government Perspective

By Cindy Williams

This paper was presented at the Bullets, Butter, and Trade: Canada/U.S. Defence Co-operation Symposium at Mewata Armoury, Calgary on 13 March 1999.

Let me begin by thanking the Strategic Studies Program and the co-sponsors for arranging this important conference and for inviting me to talk with you about industry and trade related to the United States military. I should mention that although I have worked for the American government for many years, I am currently not in government service. Nevertheless I will try to articulate the government’s perspective as I understand it.

To put things in context, I will start with a brief discussion of the American budget for defense, and particularly the part of the budget that is devoted to research, development, testing, and engineering (RDT&E) and procurement. Then I would like to make a few remarks about the consolidation that has occurred in the American defense and aerospace industries during the past 15 years, and what it might mean for firms that are looking to do business with the United States military. As David Bercuson discussed in his talk yesterday, the United States and Canada have a unique relationship in the areas of national security, collective defense and defense trade, and I want to spend a few minutes talking about that. I will end with a brief review of some recent changes in United States policy that will affect the way a company does business with the military.

The U.S. Defense Budget

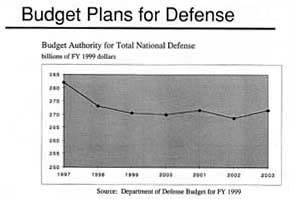

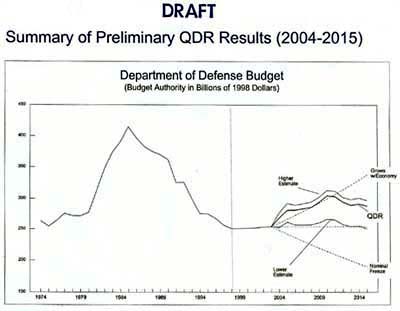

Let me begin with some facts and figures about the American defense budget. In 1999, the United States will spend US$277 ($415 Canadian) billion-about 16 percent of the total federal budget-on defense. Most of that money, about US$263 billion, will be spent by the military through the Department of Defense. Most of the remainder will go to the Department of Energy for its nuclear weapons programs. Defense spending is considerably lower in real terms-that is, after adjusting for inflation-than it was in the mid-1980s, but it is higher than it was in the mid-1960s or mid-1970s.

Let me begin with some facts and figures about the American defense budget. In 1999, the United States will spend US$277 ($415 Canadian) billion-about 16 percent of the total federal budget-on defense. Most of that money, about US$263 billion, will be spent by the military through the Department of Defense. Most of the remainder will go to the Department of Energy for its nuclear weapons programs. Defense spending is considerably lower in real terms-that is, after adjusting for inflation-than it was in the mid-1980s, but it is higher than it was in the mid-1960s or mid-1970s.

Of the $263 billion earmarked for the Defense Department, the lion’s share-US$98 billion-goes to operation and maintenance. Another US$71 billion pays salaries and bonuses for the 1.4 million active duty troops and 1.3 million reservists, and a few billion dollars goes to military construction and family housing. The rest is devoted to military acquisition-US$37 billion to RDT&E and US$49 billion to procurement.

Of the $263 billion earmarked for the Defense Department, the lion’s share-US$98 billion-goes to operation and maintenance. Another US$71 billion pays salaries and bonuses for the 1.4 million active duty troops and 1.3 million reservists, and a few billion dollars goes to military construction and family housing. The rest is devoted to military acquisition-US$37 billion to RDT&E and US$49 billion to procurement.

The budget that President Clinton submitted to Congress in January 1999 calls for 21 percent real growth in military procurement spending between now and 2004, but a small decline in RDT&E spending in real terms. If the President’s plan is realized, RDT&E and procurement funding combined will reach US$104 billion (current dollars) by 2004.

The budget that President Clinton submitted to Congress in January 1999 calls for 21 percent real growth in military procurement spending between now and 2004, but a small decline in RDT&E spending in real terms. If the President’s plan is realized, RDT&E and procurement funding combined will reach US$104 billion (current dollars) by 2004.

It would be unrealistic to count on these amounts for military acquisition over the next five years, however. The reason is that the United States is having its own “bullets vs. butter” problems inside the military. The American military has found it very difficult since the end of the Cold War to reduce its spending on infrastructure-upkeep of military bases, administration, schoolhouse training, health care for military personnel and their families, and so on.  As a result, the share of the defense budget devoted to operation and maintenance has grown each year, while plans for increasing procurement spending have not been realized. Unless the Department gets a major boost in its budget or is able to reduce its infrastructure significantly (for example by closing fifty or a hundred more military bases), carving out this 21 percent increase for procurement will be extremely difficult.

As a result, the share of the defense budget devoted to operation and maintenance has grown each year, while plans for increasing procurement spending have not been realized. Unless the Department gets a major boost in its budget or is able to reduce its infrastructure significantly (for example by closing fifty or a hundred more military bases), carving out this 21 percent increase for procurement will be extremely difficult.

But even if there is no increase, the US$86 billion that the United States will spend this year on military acquisition is a huge amount by anybody’s standards. And Canadian firms should have access to a sizeable portion of that amount.

Consolidation in the U.S. Defense Industry

One thing that may make it difficult for Canadian firms to compete for that money is the unprecedented wave of consolidations in the U.S. defense and aerospace industries. Since 1985, mergers and acquisitions have led to the consolidation of 36 American aerospace companies into four: Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, and Northrop Grumman. The depth and breadth of companies like these gives them enormous leverage in winning Defense Department contracts. Their size gives them staying power through the long process of bidding and negotiation. The breadth of their traditional customer bases puts them in a position to propose systems that meet the demands of multiple services, a big plus as the Defense Department seeks to stretch constrained investment budgets through joint purchases. And their people offer a base of experience that translates into formidable competition across the spectrum of defense systems. They represent a huge competitive force to be reckoned with, both for smaller American companies and for international ones.

Last year, the U.S. government prohibited the merger of Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman on anti-trust grounds. Thus, it seems consolidation at the prime contractor level has gone as far as it can in the United States. Many observers now believe that the merger mania that took hold of the primes is about to be felt among the second- and third-tier companies as well. In this environment, a Canadian contractor looking to attract Defense Department business would do well to identify a niche that is not covered by one of the giants and team either with a big company or with other smaller firms, perhaps as a supplier, a subcontractor, or a strategic partner.

Canada-U.S. Trade Relationship

The relationship between Canadian and U.S. defense industries is part of a wider partnership of trade and investment between the two countries. The Canada-United States trading partnership is the largest in the world. Each country is the other’s largest trading partner: 80 percent of Canada’s merchandise exports go to the United States and 77 percent of its merchandise imports come from south of the border. On the American side, 22 percent of exports and 20 percent of imports are with Canada. Moreover, 68 percent of the foreign direct investment in Canada is U.S.-owned, and Canadian companies account for a large segment of foreign direct investment in the United States.

On the defense side, two-way trade between the two countries comes to billions of dollars. Recent American military purchases include armored personnel carriers and Bell helicopters. The Army, Air Force, and Navy are all considering purchases of Bombardier’s Guardian unmanned aerial vehicle. Conversely, the Canadian military has recently purchased C-130 transport airplanes and also a variety of weapons and radars for the Halifax frigates from American firms. And the Canadian Forces plans to buy software and mission computers to upgrade its CF-18 fighters from American companies as well.

The U.S. and Canadian industrial and technology bases for defense already seem to be quite integrated. Several American aerospace and defense companies have major subsidiaries in Canada. And U.S. defense trading with Canada is more open than with any other country. Special exemptions to American export laws grant Canada license-free imports of unclassified defense articles, services, and technical data from American companies. This open border policy, however, may be in jeopardy because the U.S. State Department, under considerable pressure from the American legislative houses, has proposed amending its regulations on international arms traffic to end the unrestricted cross-border defense trade. Although it is still too early to tell exactly what long-term effect these proposed changes might have on the relationship, if such restrictions are put in place, Canadian companies will face far more bureaucratic obstacles and paperwork in competing for American contracts.

Changes in Procurement Policy

The Defense Department is instituting some new ways of doing business that its trading partners should be aware of. The changes stem from multiple forces working on the Department: a desire within the Department to transform itself for the future after the Cold War ended; lessons learned in the Gulf War about the value of technology, especially information technology; and a government-wide thrust for procurement reform.

The government-wide thrust has resulted in two pieces of legislation: the Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act and the Clinger-Cohen Act on the management and procurement of information technologies and services. These acts significantly simplify the government acquisition process for less expensive items, encourage the purchase of commercial off-the-shelf items whenever possible, and streamline the process by which equipment users and acquisition agents define their requirements. The acts are intended to free acquisition agents from an array of cumbersome procedures that have slowed down the government’s purchases in the past. In response to the new laws, the executive branch, including the Department of Defense, is reviewing and re-writing federal regulations to streamline procedures throughout the acquisition process.

In transforming itself to meet the future, the Defense Department asserts that it is on the threshold of two revolutions: a revolution in military affairs and a revolution in business affairs. Both of these so-called revolutions have implications for firms doing business with the Department in the coming years.

Proponents of a revolution in military affairs argue that recent advances in information technologies and other areas make it possible for the United States to gain information superiority on the battlefield-that is, to collect, process, and disseminate a steady flow of information to U.S. and allied forces, while denying an opponent the ability to gain and use information. The emphasis on information technologies shows up in the budget for fiscal year 2000, which boosts spending in the information areas by several billion dollars compared with previous plans. One upshot of the perceived revolution is that the Pentagon is actively seeking cutting edge technologies in the information sector.

But the Department knows that new technologies and weapons are only as good as the warfighting concepts that employ them. As a result, there is currently a heavy emphasis in all three military services on warfighting experimentation to explore the usefulness of new equipment and to develop new military operational concepts and doctrine. The Air Force even goes so far as to say that all of its future procurements will be based on knowledge gained from its annual warfighting experiment, called the Expeditionary Force Experiment. The Services have also built battle laboratories that are responsible for identifying useful new technologies.

For a contractor with a new idea, especially in the information areas of sensing, command and control, or communications, the battle laboratories and warfighting experiments offer a key avenue for getting into the defense procurement cycle. Bombardier has discovered this route, and has entered its Guardian air vehicle for testing at the Air Force’s Unmanned Aerial Vehicle battle lab in Florida.

Let me turn now to the revolution in business affairs. Through this so-called revolution, the Department of Defense hopes to adopt the best business practices of the private sector for conducting the business of defense. For a supplier, the goals that will have the most impact are in the area of electronic business operations. For example, the Department wants all phases of the contracting process to be paper-free by the end of this year. Also, in the future, industry partners and the public will get access to financial information, requirements and specifications, and government regulations and standards only through the Internet or CD-ROM. There will be no paper products. The same goes for government payments, which will be made strictly through electronic funds transfer. Most purchases of goods and services under US$2,500 will be made using a government VISA card called IMPAC. And the Department is setting up electronic catalogs and electronic “shopping malls,” through which suppliers can sell directly to government purchasers after negotiating terms and prices with a central contracting organization like the Defense Logistics Agency.

A related Defense Department initiative is price-based acquisition, which will free suppliers from having to track and disclose the cost of labor and materials for every segment of a work breakdown structure to the government’s contracting officer. Under the new plan, suppliers will simply tell the government the price of each element of a system. Price-based acquisition will bring military buying procedures closer to those of the commercial world and will help the government streamline its outdated auditing and accounting mechanisms.

None of these initiatives is an unalloyed boon to trading partners, especially to partners who already have the structure in place to do business with the Defense Department the old way. But they do seem to be the way of the future, and firms looking to extend an existing trade relationship or start a new one with the Defense Department should try to learn everything they can about them.

Summary

Despite the post-Cold War cutbacks, the U.S. military is still spending a huge amount of money on research and development and procurement. The Defense Department plans for growth in those areas over the next five years, but its hopes may not be realized as budgetary pressures inside and outside of the Pentagon continue to be felt. The virtually unrestricted cross-border defense trade between the United States and Canada puts Canadian firms in a good position to compete for that money. Knowledge-based exports like information and telecommunications systems will be especially sought after because of the Pentagon’s emphasis on information superiority.

In these days of the mega-corporation, however, it will be difficult for any supplier not among the top twenty or thirty to compete. Therefore smaller companies will want to consider strategic alliances with other firms. And any company planning to do business with the American military should prepare to do most of its business electronically in the very near future. Still, the potential rewards for Canadian companies seeking to gain a small share of the lucrative U.S. defense market make the effort more than worthwhile. Should the Canadian defense budget continue its current downward trend, the amount of money available for new equipment purchases and similar procurements in Canada will likely be limited. Thus, many Canadian defense-related companies, including those counted as the traditional suppliers of the Canadian Forces, may need more American business in order to survive over the short and long terms. The challenge is finding out what the U.S. Defense Department wants and how to navigate successfully the elaborate procurement processes of the different services. At the same time, expect stiff competition from American firms competing for the same contracts.