|

|

|

|

Foreign Affairs

When the Shiites Rise

Vali Nasr

VALI NASR is a Professor at the Naval Postgraduate School, an Adjunct Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, and the author of The Shia Revival: How Conflicts Within Islam Will Shape the Future.

IRAQ THE MODEL

The war in Iraq has profoundly changed the Middle East, although not in the ways that Washington had anticipated. When the U.S. government toppled Saddam Hussein in 2003, it thought regime change would help bring democracy to Iraq and then to the rest of the region. The Bush administration thought of politics as the relationship between individuals and the state, and so it failed to recognize that people in the Middle East see politics also as the balance of power among communities. Rather than viewing the fall of Saddam as an occasion to create a liberal democracy, therefore, many Iraqis viewed it as an opportunity to redress injustices in the distribution of power among the country's major communities. By liberating and empowering Iraq's Shiite majority, the Bush administration helped launch a broad Shiite revival that will upset the sectarian balance in Iraq and the Middle East for years to come.

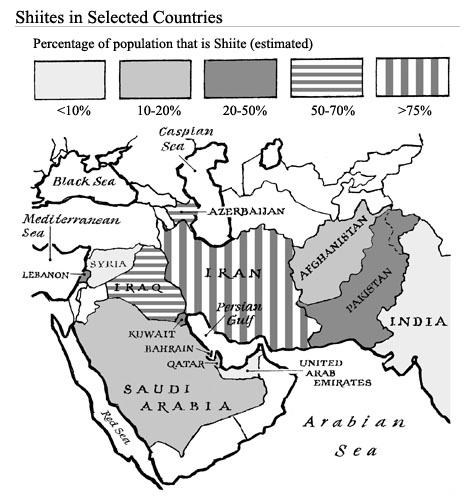

There is no such thing as pan-Shiism, or even a unified leadership for the community, but Shiites share a coherent religious view: since splitting off from the Sunnis in the seventh century over a disagreement about who the Prophet Muhammad's legitimate successors were, they have developed a distinct conception of Islamic laws and practices. And the sheer size of their population today makes them a potentially powerful constituency. Shiites account for about 90 percent of Iranians, some 70 percent of the people living in the Persian Gulf region, and approximately 50 percent of those in the arc from Lebanon to Pakistan -- some 140 million people in all. Many, long marginalized from power, are now clamoring for greater rights and more political influence. Recent events in Iraq have already mobilized the Shiites of Saudi Arabia (about 10 percent of the population); during the 2005 Saudi municipal elections, turnout in Shiite-dominated regions was twice as high as it was elsewhere. Hassan al-Saffar, the leader of the Saudi Shiites, encouraged them to vote by comparing Saudi Arabia to Iraq and implying that Saudi Shiites too stood to benefit from participating. The mantra "one man, one vote," which galvanized Shiites in Iraq, is resonating elsewhere. The Shiites of Lebanon (who amount to about 45 percent of the country's population) have touted the formula, as have the Shiites in Bahrain (who represent about 75 percent of the population there), who will cast their ballots in parliamentary elections in the fall.

Iraq's liberation has also generated new cultural, economic, and political ties among Shiite communities across the Middle East. Since 2003, hundreds of thousands of pilgrims, coming from countries ranging from Lebanon to Pakistan, have visited Najaf and other holy Shiite cities in Iraq, creating transnational networks of seminaries, mosques, and clerics that tie Iraq to every other Shiite community, including, most important, that of Iran. Pictures of Iran's supreme religious leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and the Lebanese cleric Muhammad Hussein Fadlallah (often referred to as Hezbollah's spiritual leader) are ubiquitous in Bahrain, for example, where open displays of Shiite piety have been on the rise and once-timid Shiite clerics now flaunt traditional robes and turbans. The Middle East that will emerge from the crucible of the Iraq war may not be more democratic, but it will definitely be more Shiite.

It may also be more fractious. Just as the Iraqi Shiites' rise to power has brought hope to Shiites throughout the Middle East, so has it bred anxiety among the region's Sunnis. De-Baathification, which removed significant obstacles to the Shiites' assumption of power in Iraq, is maligned as an important cause of the ongoing Sunni insurgency. The Sunni backlash has begun to spread far beyond Iraq's borders, from Syria to Pakistan, raising the specter of a broader struggle for power between the two groups that could threaten stability in the region. King Abdullah of Jordan has warned that a new "Shiite crescent" stretching from Beirut to Tehran might cut through the Sunni-dominated Middle East.

Stemming adversarial sectarian politics will require satisfying Shiite demands while placating Sunni anger and alleviating Sunni anxiety, in Iraq and throughout the region. This delicate balancing act will be central to Middle Eastern politics for the next decade. It will also redefine the region's relations with the United States. What the U.S. government sows in Iraq, it will reap in Bahrain, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere in the Persian Gulf.

Yet the emerging Shiite revival need not be a source of concern for the United States, even though it has rattled some U.S. allies in the Middle East. In fact, it presents Washington with new opportunities to pursue its interests in the region. Building bridges with the region's Shiites could become the one clear achievement of Washington's tortured involvement in Iraq. Succeeding at that task, however, would mean engaging Iran, the country with the world's largest Shiite population and a growing regional power, which has a vast and intricate network of influence among the Shiites across the Middle East, most notably in Iraq. U.S.-Iranian relations today tend to center on nuclear issues and the militant rhetoric of Iran's leadership. But set against the backdrop of the war in Iraq, they also have direct implications for the political future of the Shiites and that of the Middle East itself.

THE IRANIAN CONNECTION

Since 2003, Iran has officially played a constructive role in Iraq. It was the first country in the region to send an official delegation to Baghdad for talks with the Iraqi Governing Council, in effect recognizing the authority that the United States had put in power. Iran extended financial support and export credits to Iraq and offered to help rebuild Iraq's energy and electricity infrastructure. After former Prime Minister Ibrahim al-Jaafari's Shiite-led interim government assumed office in Baghdad in April 2005, high-level Iraqi delegations visited Tehran, reached agreements over security cooperation with Iran, and negotiated a $1 billion aid package for Iraq and several trade deals, including one for the export of electricity to Iraq and another for the exchange of Iraqi crude oil for refined oil products.

Iran's unofficial influence in Iraq is even greater. In the past three years, Iran has built an impressive network of allies and clients, ranging from intelligence operatives, armed militias, and gangs to, most visibly, politicians in various Iraqi Shiite parties. Many leaders of the main Shiite parties, the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI) and Dawa (including two leading party spokesmen, former Prime Minister Jaafari and the current prime minister, Nouri al-Maliki), spent years of exile in Iran before returning to Iraq in 2003. (SCIRI's militia, the Badr Brigades, was even trained and equipped by Iran's Revolutionary Guards.) Iran has also developed ties with Muqtada al-Sadr, who once inflamed passions with his virulent anti-Iranian rhetoric, as well as with factions of Sadr's movement, such as the Fezilat Party in Basra. The Revolutionary Guards supported Sadr's Mahdi Army in its confrontation with U.S. troops in Najaf in 2004, and since then Iran has trained Sadrist political and military cadres. Iran bankrolled Shiite parties in Iraq during the two elections, used its popular satellite television network al Aalam to whip up support for them, and helped broker deals with the Kurds. Iraqi Shiite parties attract voters by relying on vast political and social-service networks across southern Iraq that, in many cases, were created with Iranian funding and assistance.

The extent of these ties has displeased the U.S. government as much as it has caught it off-guard. Washington complains that Iran supports insurgents, criminal gangs, and militias in Iraq; it accuses Tehran of poisoning Iraqi public opinion with anti-Americanism and of arming insurgents. Washington failed to anticipate Iran's influence in Iraq largely because it has long misunderstood the complexity of the relations between the two countries, in particular the legacy of the war they fought during most of the 1980s. Much has been made of the fact, for example, that throughout that savage conflict -- which claimed a million lives -- Iraq's largely Shiite army resisted Iranian incursions into Iraqi territory, most notably during the siege of the Shiite city of Basra in 1982. But the war's legacy did not divide Iranian and Iraqi Shiites as U.S. planners thought; it pales before the memory of the anti-Shiite pogrom in Iraq that followed the failed uprising in 1991. Today, Iraqi Shiites worry far more about the Sunnis' domination than about Tehran's influence in Baghdad.

In addition to military and political bonds, there are numerous soft links between Iran and Iraq, forged mostly as a result of several waves of Shiite immigration. In the early 1970s, as part of his Arabization campaign, Saddam expelled tens of thousands of Iraqi Shiites of Iranian origin, who then settled in Dubai, Kuwait, Lebanon, Syria, and for the most part, Iran. Some of the Iraqi refugees who stayed in Iran have achieved prominence there as senior clerics and commanders of the Revolutionary Guards. A case in point is Ayatollah Muhammad Ali Taskhiri, who is a senior adviser to Khamenei and a doyen of the influential conservative Haqqani seminary, in Qom, where many of Iran's leading security officials and conservative clerics are educated. Taskhiri briefly returned to Najaf in 2004 to oversee the work of his Ahl al-Bayt Foundation, which has invested tens of millions of dollars in construction projects and medical facilities in southern Iraq and promotes cultural and business ties between Iran and Iraq. He is now back in Tehran, where he wields considerable power over the government's policy toward Iraq.

Throughout the 1980s and after the anti-Shiite massacres of 1991, some 100,000 Iraqi Arab Shiites also took refuge in Iran. In the dark years of the 1990s, Iran alone gave Iraqi Shiites refuge and support. Since the Iraq war, many of these refugees have returned to Iraq; they can now be found working in schools, police stations, mosques, bazaars, courts, militias, and tribal councils from Baghdad to Basra, as well as in government. The repeated shuttling of Shiites between Iran and Iraq over the years has created numerous, layered connections between the two countries' Shiite communities. As a result, the Iraqi nationalism that the U.S. government hoped would serve as a bulwark against Iran has proved porous to Shiite identity in many ways.

Ties between the two countries' religious communities are especially close. Iraqi exiles in Iran gravitated toward Iraqi ayatollahs such as Mahmoud Shahroudi (the head of Iran's judiciary), Kazem al-Haeri (a senior Sadrist ayatollah), and Muhammad Baqer al-Hakim (a SCIRI leader, killed in 2003), who oversaw the establishment of Iraqi religious organizations in Tehran and Qom. Those organizations have wielded great influence in Iran since the 1980s thanks to the role they played then in opening up the Shiites of Lebanon, who had traditionally been turned toward Najaf, to Iranian influence. Many senior clerics and graduates of the Iraqi Shiite seminaries in Iran have joined Iran's political establishment. Several judges in the Iranian judiciary, including Shahroudi, are Iraqis and are particularly close to Khamenei. And those Iraqi clerics who returned to their homeland after 2003 to take over various mosques and seminaries across southern Iraq have created an important axis of cooperation between Qom and Najaf.

So much, then, for the conventional wisdom prevailing in Washington before the war: that once Iraq was free, Najaf would rival Qom and challenge the Iranian ayatollahs. Since 2003, the two cities have cooperated. There is no visible doctrinal rift between their clerics or any exodus of dissidents from one city to the other. Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani's popular Web site, www.sistani.org, is headquartered in Qom, and most of the religious taxes collected by his representatives are kept in Iran. Despite repeated entreaties from dissident voices in Iran, senior clerics in Najaf have kept scrupulously quiet about Iranian politics, deliberately avoiding upsetting the authorities in Qom and Tehran.

This nexus extends well beyond the elites. The opening of the shrine cities of Iraq has had an emotional impact on regular Iranians, especially on the more religious social classes that support the regime. Since 2003, hundreds of thousands of Iranians have visited the holy cities of Najaf and Karbala every year. This trend has reinforced the growing popularity of devotional piety in Iran. Over the past decade, many Iranian youth have taken to adulating Shiite saints, in particular the Twelfth Imam, the Shiite messiah. Many more Iranians recognize Ayatollah Sistani as their religious leader now than did before 2003, and many more now turn their religious taxes over to him. Although largely cynical about their own clerical leaders, many Iranians have embraced the revival of Shiite identity and culture in Iraq.

Business has followed religious fervor. The Iranian pilgrims who flock to the hotels and bazaars of Najaf and Karbala bring with them investments in land, construction, and tourism. Iranian goods are now ubiquitous across southern Iraq. The border town of Mehran, one of the largest points of entry for goods into Iraq, now accounts for upward of $1 billion in trade between the two countries. Such commercial ties create among Iranians, especially bazaar merchants -- a traditional constituency of the conservative leadership in Tehran -- a vested interest in the stability of southern Iraq.

Granted, the legacy of the Iran-Iraq War, Iraqi nationalism, and, especially, ethnic differences between Arabs and Persians have historically caused much friction between Iran and Iraq. But these factors should not be overemphasized: ethnic antagonism cannot possibly be all-important when Iraq's supreme religious leader is Iranian and Iran's chief justice is Iraqi. Although ethnicity will continue to matter to Iranian-Iraqi relations, now that Saddam has fallen and the Shiites of Iraq have risen, it will likely be overshadowed by the complex, layered connections between the two countries' Shiite communities.

| Country | Percentage of population that is Shiite | Total population | Shiite population |

| Iran | 90% | 68.7 million | 61.8 million |

| Pakistan | 20% | 165.8 million | 33.2 million |

| Iraq | 65% | 26.8 million | 17.4 million |

| India | 1% | 1,095.4 million | 11.0 million |

| Azerbaijan | 75% | 8.0 million | 6.0 million |

| Afghanistan | 19% | 31.1 million | 5.9 million |

| Saudi Arabia | 10% | 27.0 million | 2.7 million |

| Lebanon | 45% | 3.9 million | 1.7 million |

| Kuwait | 30% | 2.4 million | 730,000 |

| Bahrain | 75% | 700,000 | 520,000 |

| Syria | 1% | 18.9 million | 190,000 |

| UAE | 6% | 2.6 million | 160,000 |

| Qatar | 16% | 890,000 | 140,000 |

| Notes: "Shiites" includes Twelver Shiites and excludes Alawis, Alevis, Ismailis, and Zaydis, among others. Percentages are estimated. Figures under 1 million are rounded to the nearest 10,000; figures over 1 million are rounded to the nearest 100,000. | |||

| Source: Based on data from numerous scholarly references and from governments and NGOs in both the Middle East and the West. | |||

These connections, moreover, are likely to be reinforced by the two communities' perception that they face a common threat from Sunnis. Nothing seems to bring Iraqi Shiites closer to Iran than the ferocity and persistence of the Sunni insurgency -- especially at a time when their trust in Washington, which has called for disbanding Shiite militias and making greater concessions to the Sunnis, is sagging.

SUNNI SCARES

Just five years ago, Iran was still surrounded by a wall of hostile Sunni regimes: Iraq and Saudi Arabia to the west, Pakistan and Taliban-ruled Afghanistan to the east. Iranians have welcomed the collapse of the Sunni wall, and they see the rise of Shiites in the region as a safeguard against the return of aggressive Sunni-backed nationalism. They are particularly relieved by Saddam's demise, because Iraq had been a preoccupation of Iranian foreign policy for much of the five decades since the Iraqi monarchy fell to Arab nationalism in 1958. Baathist Iraq worried the shah and threatened the Islamic Republic. The Iran-Iraq War dominated the first decade of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's revolution, ravaged Iran's economy, and scarred Iranian society.

If there is an Iranian grand strategy in Iraq today, it is to ensure that Iraq does not reemerge as a threat and that the anti-Iranian Arab nationalism championed by Sunnis does not regain primacy. Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and many leaders of the Revolutionary Guards, all veterans of the Iran-Iraq War, see the pacification of Iraq as the fulfillment of a strategic objective they missed during that conflict. Iranians also believe that a Shiite-run Iraq would be a source of security; they take it as an axiom that Shiite countries do not go to war with one another.

All this is small consolation for the Sunnis in the region, who remember the consequences of Iran's ideological aspirations in the 1980s -- and now worry about its new regional ambitions. A quarter century ago, Tehran supported Shiite parties, militias, and insurgencies in Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia. The Iranian Revolution combined Shiite identity with radical anti-Westernism, as reflected in the hostage crisis of 1979, the 1983 bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut, and Tehran's continued support for international terrorism. In the end, the Iranian Revolution fell short of its goals, and except for in Lebanon, the Shiite resurgence that it inspired came to naught.

Some say the Islamic Republic is now a tired dictatorship. Others, however, worry about the resurgence of Iran's regional ambitions, fueled this time not by ideology but by nationalism. Tehran sees itself as a regional power and the center of a Persian and Shiite zone of influence stretching from Mesopotamia to Central Asia. Freed from the menace of the Taliban in Afghanistan and of Saddam in Iraq, Iran is riding the crest of the wave of Shiite revival, aggressively pursuing nuclear power and demanding international recognition of its interests.

Leaders in Tehran who want to create a greater zone of Iranian influence -- something akin to Russia's concept of "the near abroad" -- view Tehran's activities in southern Iraq as a manifestation of Iran's great-power status. Yet none of them holds on to Khomeini's dream of ruling over Iraq's Shiites. Rather, Tehran's goal in southern Iraq is to exert the type of economic, cultural, and political influence it has wielded in western Afghanistan since the 1990s. Although Tehran clearly expects to play a major role in Iraq, it may not aim -- or be able -- to turn the country into another Islamic republic.

Predictably, Iran's growing prominence is complicating relations between sectarian groups in the region. Sunni governments have used Tehran's ambitions as an excuse to resist both the demands of their own Shiite populations and Washington's calls for political reform. Since 2003, Sunni leaders in Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia have repeatedly blamed Iran for the chaos in Iraq and warned that Iran would wield considerable influence in the region if Iraqi Shiites came to hold the reins of power in Baghdad. The Egyptian president, Hosni Mubarak, sounded the alarm last April: "Shiites are mostly always loyal to Iran and not the countries where they live." Such partly self-serving rhetoric allows Sunni leaders to divert attention away from their own responsibility for Iraq's troubles: Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia have so far supplied the bulk of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi's army of suicide bombers. It also provides them with a subterfuge to resist U.S. calls for domestic political reform. If bringing democracy to the Middle East means empowering Shiites and strengthening Iran, they argue, Washington would be well advised to stick to Sunni dictatorships.

The Sunnis' public-relations offensive worries the Iranian leadership. Despite its growing clout, Tehran needs its neighbors' support and the goodwill of "the Arab street" to resist international pressure over its nuclear program. So far, Tehran has avoided sectarian posturing and further antagonizing Sunnis; instead, it has tried to generate support in the region by escalating tensions with the United States and Israel. Iranian leaders have routinely blamed sectarian violence in Iraq, including the bombing of the Askariya shrine, in Samarra, in February, on "agents of Zionism" intent on dividing Muslims. Meanwhile, Tehran aggressively pursues nuclear power both to confirm Iran's regional status and to minimize Washington's ability to stand in its way.

A MEETING OF MINDS

Iran's aspirations leave Washington and Tehran in a complicated, testy face-off. After all, Iran has benefited greatly from U.S.-led regime changes in Kabul and Baghdad. But Washington could hamper the consolidation of Tehran's influence in both Afghanistan and Iraq, and the U.S. military's presence in the region threatens the Islamic Republic. In Iraq especially, the two governments' short-term goals seem to be at odds: whereas Washington wants out of the mess, Tehran is not unhappy to see U.S. forces mired there.

So far, Tehran has favored a policy of controlled chaos in Iraq, as a way to keep the U.S. government bogged down and so dampen its enthusiasm for seeking regime change in Iran. This strategy makes the current situation in Iraq very different from that in Afghanistan after the fall of the Taliban in late 2001, when Iran worked with the United States to cobble together the government of Hamid Karzai. Tehran cooperated with Washington at the time largely because it needed to: its Persian-speaking and Shiite clients in Afghanistan made up only a minority of the population and were in no position to protect Iran's interests. Tehran's calculus in the aftermath of the Iraq war has been different. Not only do Iran's immediate interests not align with those of the United States, but Tehran's position in Iraq is stronger than it was in Afghanistan thanks to the majority status of Shiites in Iraq. Seeing the Bush doctrine proved wrong in Iraq would be an indirect way for Iran's leaders to discredit Washington's calls for regime change in Tehran. Their recent willingness to escalate tensions with Washington over Iran's nuclear activities suggests that they believe they have largely succeeded in this goal; Iran is now stronger relative to the United States than it was on the eve of the Iraq war.

And yet, in the longer term, U.S. and Iranian interests in Iraq may well converge. Both Washington and Tehran want lasting stability there: Washington, because it wants a reason to bail out; Tehran, because stability in its backyard would secure its position at home and its influence throughout the region. Iran has much to fear from a civil war in Iraq. The fighting could polarize the region and suck in Tehran, as well as spill over into the Arab, Baluchi, and Kurdish regions of Iran, where ethnic tensions have been rising. As former Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Maleki has put it, chaos in Iraq "does not help Iranian national interest. If your neighbor's house is on fire, it means your home is also in danger." Clearly wary, Tehran has braced itself for greater troubles by appointing a majority of its provincial governors from the ranks of its security officials and Revolutionary Guard commanders.

Two groups within Iran could help convince the Iranian leadership that cooperation with Washington is in its interest. The first are Iraqi refugees, who act as a lobby for Iraqi Shiite interests in Tehran. They have encouraged Iran to pursue talks with the United States over Iraq, partly because they view Washington and Tehran as the twin pillars of their power in Iraq. The escalation of tensions between the two governments would not serve the interests of Iraqi Shiites, and that lobby does not want to see Iraq become hostage to the international standoff over Iran's nuclear program. The second important constituency is made up of the many Iranians who are greatly concerned about the sanctity of Iraq's shrine cities. Every major bombing in Najaf and Karbala so far has claimed Iranian lives. The Iranian public expects Tehran to ensure the security of those cities; its influence has already provided Khamenei with a pretext for publicly endorsing direct talks with Washington over Iraq.

Still, Iran will actively seek stability in Iraq only when it no longer benefits from controlled chaos there, that is, when it no longer feels threatened by the United States' presence. Iran's long-term interests in Iraq are not inherently at odds with those of the United States; it is current U.S. policy toward Iran that has set the countries' respective Iraq policies on a collision course. Thus a key challenge for Washington in Iraq is to recalibrate its overall stance toward Iran and engage Tehran in helping to address Iraq's most pressing problems.

SETTING THE STAGE

The most important issue facing Iraq in the coming months will be the constitutional negotiations, particularly regarding the questions of federalism and how oil revenues will be distributed. It was only after the U.S. ambassador to Iraq, Zalmay Khalilzad, persuaded the Shiites and the Kurds to agree to change the constitution that the Sunnis participated in the referendum to ratify it in late 2005. Since then, Washington has hoped for a deal that would bring moderate Sunnis into the political process and thus weaken the Sunni insurgency. But the prospects of such a deal are uncertain. The Shiites, the Sunnis, and the Kurds are unlikely to see the wisdom of compromise without outside pressure, and the U.S. government no longer has the political capital to force concessions or satisfy the demands of one party without risking alienating another. It is the weakening of the United States' position in Iraq that makes it necessary -- more so now than in 2003 -- for Washington to reach out to Iraq's neighbors.

If the constitutional negotiations fail, the Sunnis could abandon the political process. Even if the Sunnis participate, bargaining with the Shiites may become more complicated, especially given signs of increasing turmoil in southern Iraq. Over the past three years, the Shiites have both participated politically and resisted the Sunni insurgency's provocations, largely because they have believed that backing U.S. policy would serve their interests. But if they were to conclude that Washington is now more eager to buy the Sunnis' cooperation than to reward them for their steadfastness, the Shiites might turn their backs on the political process. Such an upset could spark a Shiite uprising. The Shiites would not even need to pick up arms to pressure the United States; by virtue of their numbers alone, they can change the country's political balance. In January 2004, Sistani rallied hundreds of thousands of Shiites for five days of demonstrations against U.S. plans to base the first post-Saddam elections on a caucus system. Earlier this year, he called the crowds to the streets again to protest the Askariya shrine bombing -- and to ensure that the U.S. government understood the extent of Shiite power.

Given its clout among the Shiites in southern Iraq, Tehran could help maintain order there while the constitutional negotiations were under way. Iran could ensure that the growing rivalry among Shiite factions such as SCIRI and Sadr's troops did not spin out of control, destabilize southern Iraq, and erode government authority in Baghdad. Keeping the Shiites together and maintaining calm in the south is of singular importance to the United States, and Iranian cooperation is crucial to achieving that goal. Iran's cooperation would help address Iraq's security and reconstruction needs, as well as buttress the central government in Baghdad.

But securing such cooperation would require the United States to address broader issues in its relationship with Iran. Tehran will end its military and financial support to Shiite militias and criminal gangs in southern Iraq only if it receives broad security guarantees from Washington. The current situation in Iraq is similar to that in Afghanistan in 2001 in the way it seems to entangle U.S. and Iranian interests -- only it is more complicated and the stakes are higher. After the fall of the Taliban in Afghanistan, the United States and Iran worked closely together to bring the Northern Alliance and its Shiite component into the mainstream political process. Washington and Tehran negotiated intensely on the sidelines of the Bonn conference on the future of Afghanistan, striking deals that helped ensure the early successes of the Karzai regime. The Bonn process promised to open a new chapter in the history of U.S.-Iranian relations. But at the time, Washington had little interest in further engaging a regime it believed it would soon overthrow. It missed an important opportunity then.

Iraq's troubles today offer Washington and Tehran a second great chance not only to normalize their relations, but also to set the stage for managing future tensions between Shiites and Sunnis. The Shiites' rise to power in Iraq sets an example for Shiites elsewhere in the Middle East, and as the model is adopted or tested it is likely to exacerbate Shiite-Sunni tensions. Better for Washington to engage Tehran now, over Iraq, than wait for the problem to have spread through the region. Although Washington and Tehran are unlikely to resolve their major differences, especially their dispute over Iran's nuclear program, anytime soon, they could agree on some critical steps in Iraq: for example, improving security in southern Iraq, disbanding the Shiite militias, and convincing the Shiite parties to compromise.

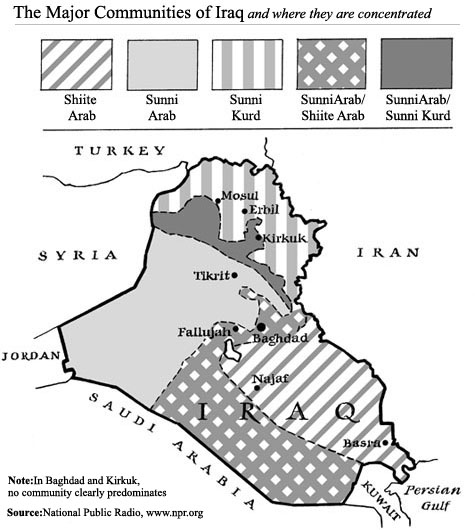

But if Washington and Tehran are unable to find common ground -- and the constitutional negotiations fail -- the consequences would be dire. At best, Iraq would go into convulsions; at worst, it would descend into full-fledged civil war. And if Iraq were to collapse, its fate would most likely be decided by a regional war. Iran, Turkey, and Iraq's Arab neighbors would likely enter the fray to protect their interests and scramble for the scraps of Iraq. The major front would be essentially the same as that during the Iran-Iraq War, only two hundred miles further to the west: it would follow the line, running through Baghdad, that separates the predominantly Shiite regions of Iraq from the predominantly Sunni ones. Iran and the countries that supported it in the 1980s would likely back the Shiites; the countries that supported Iraq would likely back the Sunnis.

Iraq is sometimes compared to Vietnam in the early 1970s or Yugoslavia in the late 1980s, but a more relevant -- and more sobering -- precedent may be British India in 1947. There was no civil war in India, no organized militias, no centrally orchestrated ethnic cleansing, no battle lines, and no conflict over territory. Yet millions of people died or became refugees. British India's professional army was sliced along communa 13bc l lines as the country was partitioned into Hindu-majority and Muslim-majority regions. Unable to either bridge the widening chasm between both groups or control the violence, the British colonial administrators were forced to beat a hasty retreat. As in Iraq today, the problem in India then lay with a minority that believed in its own manifest destiny to rule and demanded, in exchange for embracing the political process, concessions from an unyielding majority. The pervasive sectarian violence and ethnic cleansing plaguing Iraq today are ominous reminders of what happened in India some 60 years ago. They may also be a worse omen: if the situation in Iraq deteriorates further, the whole Middle East would be at risk of a sectarian conflict between Shiites and Sunnis.