CIAO DATE: 02/05/08

European Affairs

Wall Street: Master of the Universe No Longer?

J. Paul Horne

Full Text

In a shift that appears to have surprised and dismayed U.S. experts, American dominance in the world’s financial system seems to be waning as foreign rivals— including the Euro zone—win a growing share of rapidly expanding global capital markets and international financial activity. The trend has shaken many American business leaders as a worrisome symptom of declining U.S. power and influence, with negative consequences for the economy and for asset prices in New York and other U.S. markets. Needless to say, in Europe and elsewhere, the development is viewed as long-overdue recognition that Manhattan, however lively its trading zeitgeist and reputation for financial power, had no monopoly on skill at deal-making, innovative financing, nose for new ventures— or even the kind of greed that drives people to succeed in the most competitive markets.For decades, the world has thought of Wall Street as the uncontested leader of global capital markets. Equities, bonds, investment banking, M&A, IPO’s, derivatives, private equity or hedge funds, you name it, U.S. markets and financial institutions were Number One for decades. It was not just in the lead, but actually far ahead of European, Japanese and other rivals. But that lead was perhaps not a permanent one. The recent data suggests American dominance is waning as other international financial marketplaces, especially London and to a lesser degree other European financial centers, gain ground and clout.

Are we seeing a tectonic shift? The question was debated by financial, corporate and government rainmakers at this year’s World Economic Forum in Davos on the theme Shaping the World Agenda: The Shifting Power Equation. The mere fact of the debate was symptomatic of spreading concern amid mounting statistical and anecdotal evidence. The Davos conclave concluded that rapid globalization means “we are living in an increasingly schizophrenic world where economies are booming and global signs are promising, but underneath are economic, political and social risks as well as imbalances and inconsistencies.”

In a geo-political sense, the Forum participants agreed that “while the U.S. remains the dominant world power, its position is increasingly challenged or constrained by new emerging players such as China and resource-rich Russia, as well as states with nuclear capabilities and ambitions such as North Korea and Iran.”

The U.S. decline in global capital markets was confirmed recently by two authoritative groups of financial experts who urged action to protect the competitiveness of U.S. capital markets. The first, the Committee on Capital Markets Regulation (CCMR), was created last summer at the urging of Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson. Representing major U.S. financial, investor, legal, accounting and academic institutions, the CCMR analyzed the reasons for and economic consequences of the U.S. decline in global capital markets.1 Public capital markets are the principal vehicle with which companies raise and price capital, and individuals and institutions invest. So they play a “vital role in the U.S. economy,” accounting for over eight percent of GDP and five percent of private sector employment, the CCMR said in its initial report last November. Its findings emphasized that U.S. economic vitality depends on its financial markets remaining competitive enough to finance the U.S. economy’s ever-growing appetite for capital and to ensure that there is enough liquidity in the market for buying and selling to grow unabated.

Now this level of performance seems to be becoming more problematic for U.S. capital markets—partly because of increased U.S. regulatory constraints on business and markets. The CCMR recommended easing some of these rules in order to facilitate business domestically and reduce incentives for big capital deals to migrate to rival financial centers in Europe that are growing in scale and sophistication.

Similar conclusions were reached by McKinsey & Co., in a recent 145-page report that concluded there is “urgent need for concerted but balanced action at the national, state and local levels to maintain the competitiveness of U.S. financial markets and New York’s role as a global financial center.” The report, released in late January, was commissioned by New York City Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, a Republican, and Democratic Senator Charles E. Schumer. Entitled Sustaining New York’s and the U.S.’s Global Financial Services Leadership, it was based on interviews with CEOs and executives of financial services companies and with investor, labor and consumer groups. Like the CCMR, the report recommended easing the regulatory environment. And it urged that immigration restrictions be eased for highly skilled workers and that New York City consider creating an international financial services zone offering tax incentives for clients who want to do their business in Manhattan.

Urgent appeals to roll back regulatory constraints on U.S. business and finance highlighted a high-level conference of financial and business leaders convened by Treasury Secretary Paulson and the Securities and Exchange Commission in Washington on March 12 and 13. The CCMR and Schumer-Bloomberg (McKinsey) reports, as well as a more recent one by the United States Chamber of Commerce, were cited as evidence that burdensome regulations and accounting transparency are causing U.S. business and finance to lose global competitiveness. It was noteworthy, however, that former Federal Reserve Chairmen Alan Greenspan and Paul Volcker joined former SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt and investor Warren Buffett to argue in favor of maintaining requirements for corporate accountability and transparency.

The CCMR and Schumer-Bloomberg reports cited a deluge of evidence, much of it linked with “equities” (essentially shares in companies), demonstrating the relative decline in U.S. domination of global finance.

• Equity market indices in Europe and Asia out-performed (in local currency terms) their rivals in comparable U.S. equity markets since 2003. Appreciation of the euro and the Chinese yuan (CNY) against the dollar (USD) during this period meant dollar investors would have made even more investing in the Euro zone or Chinese equity markets than in dollars because of the exchange- rate premium. (See Figure 1 —Major Equity Market Trends.)

• The U.S. share of global equity market activity was 50 percent in 2005, down from 60 percent in 2000 at the height of the “dot.com bubble.” (See Figure 2—Share of Global Stock Market by Region.)

• Global equity Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) are falling off sharply in the U.S. In the late 1990s, 48 percent of them originated on U.S. exchanges, but only six percent in 2005 and an estimated eight percent last year. Of the largest global IPOs, 24 out of 25 were done outside the U.S. in 2005; last year it was nine out of 10.

• Companies issuing new equity outside their home markets also shifted away from U.S. exchanges. In 2000, 50 percent of the dollars in global IPOs were raised on U.S. exchanges, but only five percent in 2005.

• Listing and trading of foreign securities on U.S. exchanges have been declining over the past five years as major foreign markets attract a growing share of those companies. This helps explain why the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) moved recently to take over Euronext, the stock-market consortium of Paris, Amsterdam and Brussels exchanges, and London’s LIFFE. NASDAQ is trying to take control of the London Stock Exchange (LSE), whose share of global IPOs soared from five percent in 2002 to 25 percent in 2005.

• U.S.-domiciled companies doing IPOs increasingly turn to London, even though they must still comply with the reporting requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act passed in 2002 to enhance corporate governance in the wake of the scandals concerning Enron and some other major U.S. companies. Even proponents of the legislation now seem inclined to view some of its provisions as too harsh in terms of the costs of reporting on compliance.

• Foreign companies increasingly issued equity to large U.S. institutional investors under Rule 144A allowing them to avoid the additional Sarbanes-Oxley scrutiny associated with publicly-listed equity IPOs. Foreign firms used this technique to raise $86 billion in 186 U.S. equity issues, versus only $5.4 billion in 34 public equity offerings in 2005.

• IPOs on the London Stock Exchange and its more loosely-regulated AIM market for small growth companies totaled $55 billion in 2005—exceeding, for the first time, the $47 billion raised on the NYSE and NASDAQ.

• The U.S. ranked only No. 5 as the best place for new business to raise capital in 2006. The Milken Institute’s Capital Access Index recently put “Hong Kong, Singapore, Britain and Canada ahead of the U.S., based on 56 quantitative and qualitative indicators used with 122 countries.”

• Employment in London’s financial services sector rose by 4.3 percent between 2002 and 2005 while New York’s dropped 0.7 percent in the same period.

• Earnings growth of U.S. financial groups, including Citigroup, Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and Lehman Brothers, was reported better outside the U.S. in 2006 than in the U.S. Much of the increased earnings originated in London and Europe. Investment banks generated more revenues from bond issuance in 2006 than from equities (including IPOs) for the first time, with much of the increase outside the U.S.

• Investment banks generated more revenues from bond issuance in 2006 than from equities (including IPOs) for the first time, with much of the increase outside the U.S.

• Outstanding debt securities issued in the euro zone were worth the equivalent of $4.83 trillion at the end of 2006, compared with $3.89 trillion for dollar debt.

• New issuance of euro-denominated debt accounted for 49 percent of total global debt in 2006. As recently as 2002, euro debt securities were only 27 percent of the total vs. 51 percent for dollar debt.

• Euro-denominated debt now accounts for 45 percent of the international (cross-border) market, compared with 37 percent for the dollar.

• The value of euro-denominated banknotes in circulation overtook dollars in circulation for the first time in 2006.

• Of the $2.7 trillion in daily foreign exchange transactions, about one third passes through London almost double the volume in 2001.

• Central banks are diversifying foreign exchange reserves away from the dollar, principally toward the euro as its credibility as a durable value grows.

• Investment banking revenues in European Union (EU) countries are gaining on the U.S., notably in IPOs and securities trading. EU banks' revenues from derivatives trading already exceed those of U.S. competitors.

• Capital-market revenues in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, are forecast to soon overtake those in the U.S., the McKinsey report said, with London and the EU replacing the U.S. as “the financial powerhouse in terms of top-line numbers.”

• Total U.S. financial assets, measured as a share of GDP, were four times U.S. GDP at end-2005. European financial assets were three times the region’s GDP, but the European ratio had grown six percent a year since 1996, double the growth rate of U.S. assets.

Four causes of the U.S. decline were identified by the CCMR (and endorsed by the McKinsey study): 1) increased trust in the integrity of major foreign public markets as a result of more transparency and better disclosure; 2) a relative increase in the liquidity of these foreign and private markets, making it less necessary for foreign firms to tap the U.S. public equity market for capital; 3) technological improvements enabling U.S. investors to invest in foreign markets; and 4) restrictive changes in the governance and regulation of U.S. public markets at a time when foreign and private market alternatives were gaining credibility.

While the CCMR and McKinsey reports focused attention on U.S. markets’ loss of competitiveness and its potential economic consequences, critics note that they may also be self-serving. The groups explicitly seek to roll back the increased regulatory constraints imposed on business following the epidemic of U.S. corporate scandals that erupted in 2001. (In 2002, I wrote an analysis of the economic and investment impact of large-scale corporate corruption on U.S. financial markets’ international standing in an article entitled “Enronitis.”2)

The post-Enron Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 significantly tightened accounting, management and transparency requirements for U.S. business, especially those which are publicly traded. The act set up the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board to oversee, for the first time, U.S. accounting firms. The CCMR and McKinsey reports attribute part of relative U.S. decline in global capital markets to the dissuasive influence of this tougher regulatory environment, including the actual costs of compliance with new standards.

Both the CCMR and McKinsey reports urge that the regulatory environment be relaxed to help preserve U.S. competitiveness. But these reports fail to take enough account of the possibility that such newly-enhanced regulatory vigilance may now be helping restore international investor confidence in the integrity of U.S. corporate governance, financial reporting and market efficiency. And that this restored confidence may encourage capital flows to the U.S., helping finance our external deficit and invest in U.S. business.

Erosion of the U.S.’s preeminence in global capital markets is also due to underlying factors, some cyclical and some long-term. Cyclical factors include the exceptionally tough domestic competition among U.S. financial institutions for market share following the dot.com and equity market bust in 2000-2002. A more restrictive interest rate environment was imposed by the Federal Reserve after June 2004, resulting in higher capital costs in the United States. The U.S. economic cycle, which has benefited from a booming residential housing market, strong corporate profits and improving labor-productivity growth, may also be running out of steam. This is reflected in stock markets’ performance (as measured by the Wilshire 5000 index which represents about 97 percent of publicly traded equities). The long, rising boom in the U.S. stock market - which took blue-chip stocks from a 2003 low to a record high on February 20— may be peaking, as evidenced by the nasty correction in early March.

Cyclical interest rate and economic factors in Europe, Japan and Asia currently appear more attractive to international investors. The European Central Bank (ECB) has cautiously managed an anti-inflationary monetary policy in the 13 countries of the single euro currency zone, and that record—controversial with some EU governments (notably those outside the euro zone, especially London)—has built up the ECB’s credibility with international investors. The Bank of Japan has been similarly prudent in stimulating a significant economic recovery without inflationary pressures.

The result is that euro zone and Japanese short-term interest rates are lower than those in the U.S. Because inflationary expectations are also lower, 10- year government bond yields are also lower outside the U.S. These cyclical factors explain why foreign firms’ cost of capital may be lower than those in the U.S.

Other cyclical factors include: corporate cost-cutting and restructuring; investment in technology to bring productivity gains; and increased emphasis on international marketing. Similar belt tightening boosted gains in profits and share prices in the U.S. since the mid- 1990s, but the relative benefits may be fading for the U.S. today. Now the same methods, applied in recent years in Europe and Japan, have sharply boosted growth in their profits and stock-market levels, with the change relative to the U.S. becoming evident since 2004.

These cyclical factors also contributed to exchange-rate changes that, since the dollar’s peak in 2002, have favored the euro, sterling and yen over the U.S. dollar. As a result, investors, especially those with dollars, now are starting to anticipate gains thanks to exchange rate moves that increase their returns on investments in the euro zone and Japan. The same reasoning applies to China, whose policy of slow yuan appreciation against the dollar encourages foreign investment in Chinese assets and markets in anticipation of bonus returns based on moves in the exchange rates against the dollar. (Such cyclical factors, especially monetary policy and equity market performance, could change during the next several years, or even months, to the detriment of Europe and Japan, allowing the U.S. to recover relative attractiveness.)

Perhaps more important for the long-term outlook for the U.S.’s relative position in global capital markets (as well as the vanity of Wall Streeters accustomed to being Masters of the Universe), there seem to be sea changes in irreversible macroeconomic and policy-related areas in the global economy and capital markets. These are already causing a long-term relative decline for the United States as the world’s single largest economy and capital market.

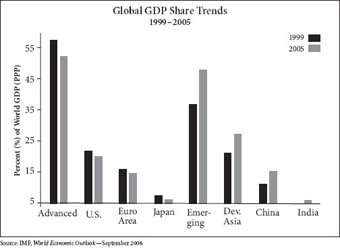

These long-term changes include the much faster economic growth of China, India and other emerging markets, which insures that the U.S. share of world GDP is declining and will continue to over the next decade or so. (See Figure 3—Global GDP Share Trends 1999-2005.) The resulting global competition for scarce energy and mineral resources means more U.S. resources must be diverted from consumption, a shift liable to have the effect of slowing overall growth.

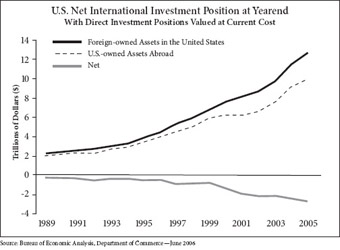

The U.S. faces a structural shortfall of savings for investment as a result of a long-term trend of over-consumption and declining savings. This leads to a large balance of payments deficit that must be financed with foreign capital. Foreign borrowing by the U.S. has led to accumulating foreign obligations to the point where, once the world’s largest creditor nation, the United States has become the largest international debtor. (See Figure 4—U.S. Net International Position at Yearend.)

Given the intractability of correcting these structural imbalances in the U.S., international investors are increasingly worried that the dollar will not be a long-term store of value. Investment preferences are thus shifting away from dollar-denominated assets toward alternatives— starting with euro-denominated assets. The success of the euro as a currency, due to its being backed by the credible anti-inflationary monetary policy of the Frankfurt-based European Central Bank, taken together with Europe’s restructuring of its markets for capital, labor and products, have made Europe more competitive and the euro an attractive alternative to dollars. Rapidly growing emerging markets such as China, India, Brazil and Russia also appear to be viable destinations for global savings even though they are clearly riskier, as demonstrated by the equity market sell-off in China in early March.

Another irreversible sea change is the internationalization of investment flows as financial assets are diversified among many different countries and business shifts direct investment to the most attractive environments. The continuing internationalization of capital flows and growing concerns about the dollar seem to make it inevitable that we will see further erosion in the position of the U.S. as the leader among global capital markets.

In the long run, it appears unlikely that this trend toward a multi-polar global capital system can be halted or reversed. Today, this prospect of continued relative decline appears disagreeable to U.S. market participants, long accustomed to being Number One. But they may be overlooking the advantages of the clearly-emerging pattern that might be called, to borrow a French expression, a “multi-polar system of global capital markets.” This on-going shift from a “unipolar” system, dominated by the U.S., to one in which multiple capital markets are large and liquid enough to attract growing international investment means global diversification. In principle, that should reduce systemic risks.

At this juncture, the foreseeable risks seem unlikely to do more than slow or alter the process of globalizing financial markets. Political turmoil in China or India could impede shifts in gross domestic product growth that currently favor Asia. European markets could be dealt a major blow by the emergence of greater reluctance to continue the painful process of restructuring labor markets and fiscal imbalances, or of failures to reform governance in the 27 EU countries, or a loss of credibility for the euro. At the outer edge of probability, the American consumer might decide to cut back spending and rebuild savings, thereby reducing U.S. borrowing abroad. This would lead, however, to a period of slower economic growth and a reduced rise in corporate profits, with hard-to forecast consequences for U.S. and international financial markets.

As an overall assessment, it seems that today’s globalization of capital markets is reaching a trajectory with its own inertial force. If so, it will very likely continue readjusting the relative importance of national and institutional players, notably by reducing U.S. predominance. Underlying structural pressures may reemerge at times to slow these changes with cyclical developments. But such periods are likely to be temporary. Meanwhile, although the United States may be losing its Number One ranking in certain markets or financial activities, it will remain, for the foreseeable future, the only single country with such large liquid capital markets and competitive financial and business institutions—a position of strength underpinned by the world’s largest and most dynamic economy.

One major caveat must hang over any assessment of the internationalization of capital markets. The absolute size of the U.S. economy and its capital markets, and the quantity of dollars invested around the world, ensure that any major U.S. economic or market downturn is very likely to trigger similar problems in Europe, Japan and Asia. That is what has happened in the past, and it continues to be highly probable in any foreseeable partial redistribution of the cards in terms of global capital markets. The U.S. also has an asset confirmed by history: Experience shows that in a crisis, investors have a traditional reflex of seeking refuge in stability and size, where the U.S. is the leader and will remain so in absolute terms for the foreseeable future. A crisis could be expected to accelerate foreign capital flows back to the U.S. once again and, in the process, slow the now-accelerating process of globalization of capital markets.

1 The Committee on Capital Markets Regulation is an independent, bipartisan committee of 22 corporate and financial leaders representing the investor community, business, finance, law, accounting and academia, announced on September 12, 2006. Co-Chaired by Glenn Hubbard, Dean of Columbia School of Business, and John Thornton, Chairman of the Brookings Institution, the CCMR issued an interim report on November 30, 2006 evaluating the competitiveness of U.S. capital markets.

2 “Does Enronitis Threaten the Dollar and the Economy? American and French Views” by J. Paul Horne and Albert Merlin in Business Economics (National Association for Business Economics) in October 2002. See: http://nabe.com/publib/be/c20024.html