|

|

|

|

|

|

European Affairs

European Economic Reform

The ECB Must First Break the Policy Deadlock

By Daniel Gros, Thomas Mayer and Angel Ubide

After several years of unsatisfactory economic growth, the 12-nation euro area is stuck in a vicious cycle. Growth disappoints, plans are outlined reduce fiscal deficits below the three percent limit of the Maastricht Treaty, and governments embark on successive waves of structural reform to try to increase potential output. Year after year, however, growth disappoints again and deficits only get worse. Citizens grow tired of ever increasing demands for reforms that seem to mean only greater labor market insecurity and lower pension and health care benefits.

As the cycle persists, governments run out of political capital, voter dissatisfaction increases, and the end result is gridlock. Meetings of policy makers and pundits about the future of Europe are as festive as a funeral, ending typically in agreement that the current situation is unsustainable and that there is no clear way out.

Dissatisfaction is widespread: the European Parliament elections in June 2004 showed a high level of discontent with Europe's economic performance, and in almost all countries governing parties suffered sharp setbacks.More recently, regional elections in Eastern Germany, and the ritual of "Monday demonstrations against changes to the welfare state," showed that the German electorate is increasingly willing to vote for extremist parties that are opposed to any reforms. How did Europe end up in this sorry state? In addition to general opposition to any cutback in lavish welfare benefits, Europeans are rapidly growing older and do not want to renounce the generous pensions that they regard as hard earned "acquired" rights. Governments, however, are finding it ever more difficult to pay out all the pensions implicitly promised under the dominant "pay-as-you" go systems in continental EU countries. Their attempts to do so have led to higher payroll taxes, and thus higher labor costs, with the predictable effect of boosting structural unemployment and lowering economic growth.

The long run challenge is well known: by 2050 the number of pensioners relative to those of working age will double for the EU-15 (the fifteen EU member states before the Union's enlargement to 25 members in May 2004). If the income of the elderly is to be kept constant in relation to the average income of the entire population, all other things being equal, spending on pensions will have to double. Since pensions expenditure is already above ten percent of Gross Domestic Product in most member states, this would mean increasing total government expenditure by over ten percent of GDP from present levels already close to 50 percent of GDP (even without taking higher health care costs into account). The pressure on public budgets - and "crowding" out the private sector - will thus become extreme in the longer run.

Less well known is that aging is also having an impact on trend growth, and not only for the next generation. Europeans stopped reproducing at the rate necessary to maintain current population levels about a generation ago. This implies that the work force will soon stop growing and will be missing its most productive elements. The consequences of this for potential growth can be seen by looking at the ratio of the working age population to overall population. Other things being equal, changes in this ratio show how far demographic developments affect the scope for redistribution of economic resources. If the ratio increases by one percent, for example, potential GDP per capita should also go up by one percent, provided other factors such as productivity and employment rates remain the same. A fall in the ratio indicates a decline in potential GDP per capita, implying that there is less to re-distribute to pensioners and other interest groups.

"By 2050 the number of pensioners relative to those of working age will double for the EU-15"

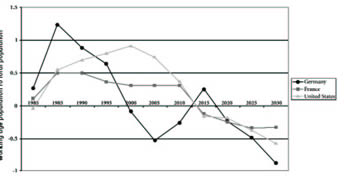

Perhaps the country suffering most from this problem is Germany, which is why it has become much more difficult to reorganize the German economic and social system in recent years. During the five years preceding reunification, demographic factors provided a strong tailwind for economic policy as the ratio of working age population to total population was increasing by about 0.8 percent a year. This was the result of a falling birth rate at a time when the rise in the number of pensioners was still moderate. During the five years up to 2005, on the other hand, demographic factors acted as a head wind to economic policy. As the graph on page 80 shows, the German ratio will improve sharply for about ten years, starting in 2005, because of the impact of World War II. During the War, birth rates collapsed and thus the increase in the number of retirees slows sharply 60 years later. After 2015, however, the steep long-term decline in the German ratio is due to resume.

The total dependency ratio started to fall rapidly after 1995, with the deterioration during the last five years equivalent to about 0.54 percent a year, as the "benefits" from fewer children were overtaken by the "costs" of more pensioners. The total deterioration in potential output growth between the late 1980s and now thus amounts to almost 1.5 percent a year. The German economic system, which until the end of the 1990s could count on a demographic bonus each year, in the form of less private and public spending on children, was simply not prepared for this change. The sails had been set for a following breeze, and the ship of state could not adjust to the fact that it is now heading into the wind. It is interesting that France is in a quite different situation: given its higher birth rate, demographic change is coming more slowly, with an important deterioration unlikely until the next decade. The United States is following a similar path to France, but with a somewhat more pronounced deterioration over the next ten years. The U.S. demographic ratio will change from an annual increase of 0.7 percent today to a drop of around 0.2 percent in the five years to 2015. That is equivalent to a negative change of over 0.8 percent a year over the next ten years - just when the budget deficit is supposed to be being brought back under control.

The demographic shock is thus not just a long-term problem. It is a reality that has already started to dent the growth capacity of some European countries, especially such large euro area countries as Germany and Italy. And EU enlargement does not solve the problem. On the contrary; the demographic perspective of the ten new member countries is even worse than that of the EU-15. In the latter the old age dependency ratio is projected to double, but in some new member countries the ratio might even triple over the next two generations.

To make matters worse, increases in European productivity have also slowed significantly in recent years. The growth rate of GDP per hour in the euro area has declined from about 2.6 percent in 1990-95 to less than 1.5 percent since 1995, a decline of 1.1 percentage points. Because the United States was moving in the opposite direction (statistical arguments notwithstanding, the growth rate of GDP per hour grew 0.8 percentage points during the same period), the European decline cannot be blamed on global developments.What are the idiosyncratic factors that have caused this decline in productivity growth?

Europe has not turned its back on the adoption of information technology (IT), so that cannot be the answer. In a recent report,1 we argue that the decline in productivity growth is due to two main factors: insufficient investment in non-IT intensive sectors, and a decline in labor quality. The decline in labor quality is probably associated with an increase in the share of low-skilled workers in the labor force - one of the main objectives of the labor market reforms. With unemployment levels still close to 10 percent, however, one wonders whether the fault really lies with lower skills or, more worryingly, with a mismatch of skills, and thus an inadequate education system.

What does this mean for future economic growth in Europe? To answer this question, it is important to review the objectives of the Lisbon Agenda, adopted by EU leaders in 2000, which is intended to make the European Union the world's most technologically competitive economy by 2010. One Lisbon target is to increase the employment rate by about one percentage point a year. Given population growth, this means that employment growth has to average about 1.5 percent a year until the end of the decade. If, however, current trends of investment continue despite this accelerated pace of job creation, the current shortage of capital stock will worsen. In addition, an acceleration of employment growth is likely to lead to a further decline in labor quality, as employers reach deeper into the pool of unemployed workers. Thus, if the Lisbon targets for employment rates are met, productivity growth will decline further under current investment rates. A sharp increase in investment will therefore be needed to generate productivity enhancing, sustainable growth in the euro area. This requires a continuation of structural reforms that free resources from declining sectors to be invested in growing sectors. It also requires a decline in fiscal deficits, for they crowd out much needed private investment, and thus a stricter enforcement of the European Stability and Growth Pact (SGP).

As argued above, however, insufficient growth has all but exhausted the room for fiscal consolidation and structural reform, and the risk of a collapse of the policy making structure of the European Union has increased - witness the conflict between the Commission and the Council of Ministers over the SGP. Europe is stuck in a low growth trap. There is a policy gridlock, in which those responsible for fiscal and structural policy claim their hands are bound until the economy recovers and those responsible for monetary policy call for fiscal and structural policy reforms so that interest rates can remain low. It is a critical situation requiring critical action. To break the policy gridlock, one of the players must move first, and we believe that player should be the European Central Bank (ECB). The Bank is the only EU institution with a reputation for prudent economic management and, with price stability not seriously endangered, it could afford to be more ambitious in pursuing the secondary objective of the Maastricht Treaty - contributing to the general policies of the European Union. In short, we believe that the ECB should adopt a policy that fosters investment and gives the European Union "room to grow".

It is true that agreements among governments, social partners and central banks have, at times, succeeded in kickstarting economies. But these are not normal times. The risks to price stability from a breakdown in the policy making structure of the European Union - abandonment of fiscal discipline, no structural reform, and even loss of central bank independence - are very large compared to the risks of tolerating higher growth for a while. Central banks must use careful judgment in balancing sticks and carrots. This is one of those moments where the carrots are badly needed. The ECB should say loudly and clearly that it will be patient and keep monetary policy accommodating to give fiscal and structural policy a chance to speed up reform.

A monetary carrot from the ECB at this point would have the added advantage that it might also be appropriate to re-balance growth from a global point of view. The risk of a sharp dollar correction is increasing as global imbalances (embodied by the exceptional U.S. current account deficit) widen. The European position has been that this issue is not a European problem, because the European Union is in balance. One could thus argue that the problem lies in the "excessive" surpluses in Asia that mirror the U.S. deficit. But Europe is the world's largest trading block and cannot just leave the global scene to a game between the United States and Asia. Without the extraordinary U.S. contribution to global demand, EU growth in the last two years would probably have been even lower, and the European Union might then not have been in balance. Europe has been free riding on "excessive" U.S. consumption, and should therefore contribute to the resolution of the global imbalances.

The optimal solution would be for emerging markets to run current account deficits to allow for a turn around in the U.S. current account and enable the aging developed world to accumulate net foreign assets. But the risk of a sudden balance of payments crisis makes this option unfeasible. A second best choice would be for Europe to contribute to resolving the problem by adopting policies that foster domestic demand growth and accommodate an appreciation of the euro. In view of the need for fiscal discipline, a patient monetary policy would be adequate from this perspective.

In conclusion, the euro area is at a critical juncture, with increased uncertainty about the sustainability of its policy making structure. The Stability and Growth Pact is already being twisted and partially abrogated, and the same might happen to the independence of the ECB if growth does not return. There is a limit to the patience of politicians, and if reform does not yield any growth payoff, governments may conclude that reform is no longer worth the trouble and adopt populist and myopic policies. We believe that the ECB has an important role in preventing this from happening.

Daniel Gros is the Director of the Centre for European Policy Studies. He has served on the staff of the IMF, as an advisor at the European Commission and as visiting professor at the Catholic University of Leuven and the University of Frankfurt.

Thomas Mayer is Managing Director and Chief European Economist at Deutsche Bank in London. Previously, he was Director of Euroland Economics at Goldman Sachs, Frankfurt.

Angel Ubide is Director of Global Economics at Tudor Investment Corporation in Washington, DC. He was previously Chief Economist at the French Desk of the International Monetary Fund.