|

|

|

|

European Affairs

Transatlantic Relations

The EU Starts to Find its Voice in New York

By Paul Luif

Earlier this year, the UN Security Council provided a dramatic showcase for Transatlantic differences over Iraq, both between the United States and some of its leading European allies and among the nations of the European Union themselves. After the U.S. decision to go to war was backed by Britain and Spain, and opposed by France and Germany, many concluded that deep new divisions in the West were dooming the European Union's hopes of forming a common foreign and security policy (CFSP), perhaps forever. An analysis of the European Union's longer-term UN voting record, however, suggests that the line-up over Iraq was unusual and does not reflect the underlying trends in EU policies and in relations between EU members and the United States. A strikingly different pattern emerges from a study I have recently conducted of UN votes, not in the Security Council but in the 191-member General Assembly, from the 1970s until 2002.

Among the study's conclusions are that the European Union has made considerable progress toward a CFSP in the past decade, with the EU nations achieving a relatively high degree of consensus, especially on the Middle East and on human rights. On most issues, the EU countries voted more in line with the Clinton administration than they have so far with the Bush administration, but the Middle East has always been the area of greatest disagreement with the United States.

The two nations whose positions have been noticeably closer to the United States than those of the other EU countries are the United Kingdom and, surprisingly perhaps, France. This has been true to some degree on the Middle East and to a greater degree on international security issues in general. These two countries, the European Union's only nuclear powers and only permanent Security Council members, have also been the most likely to deviate from the mainstream EU position in voting in the General Assembly. The European Union's two most influential countries have thus also tended to be the farthest away from an increasingly clearly identifiable EU mainstream position on many policy issues.

As the European Union does not yet have a legal personality, it is not officially represented as an organized group in the General Assembly, although its economic branch, the European Community, has observer status. Nevertheless, the European Union is one of the most important players in the Assembly as its 15 (soon to be 25) members are required by European treaty rules to try to reach common positions and speak with one voice in international organizations.

During meetings of the General Assembly (mostly between September and December in New York), EU diplomats make intensive efforts to agree on common statements and joint positions on UN resolutions. In the second half of 2002, for instance, the Danish EU Presidency convened a total of 601 coordination meetings in New York and delivered 145 formal statements on behalf of the European Union in plenary sessions and committee meetings of the General Assembly.

In contrast to the Security Council, the General Assembly can only vote on non-binding recommendations (except for UN budgetary matters). Each year the Assembly passes several hundred resolutions on a wide range of subjects including international security (in particular nuclear, but also conventional non-proliferation and disarmament), social and economic issues, de-colonization and human rights. Its resolutions also deal with specific international disputes, in particular the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The agenda of the General Assembly is largely established by the 115 developing countries that are members of the Non-Aligned Movement. Thus, EU member states, as well as the United States, have to take positions and vote on resolutions that have mainly been introduced by other countries.

About 70 to 80 percent of these resolutions are adopted by consensus, without any voting. Twenty to 30 percent are adopted or rejected by "recorded votes", in which the position of each state is made public, either "for", "against" or "abstaining". This makes it possible to calculate how far EU member states have succeeded in "speaking with one voice," i.e. how often they have cast identical votes in plenary sessions of the General Assembly, as a proportion of all their recorded votes.

The data used here show that starting in 1973, the then nine EU countries voted identically in about 60 percent of recorded votes. From the late 1970s, EU cohesion began to decline, reaching a low point in 1983, when member states cast identical votes only about 30 percent of the time. The decline was caused by renewed tensions between East and West.

Toward the end of the Cold War, in the 1980s, the EU countries differed over moves to strengthen NATO's military defenses by deploying intermediate range nuclear forces in Europe and President Ronald Reagan's firm policies toward the Soviet Union. The admission of Greece in 1981 led to a particularly sharp increase in internal discord. The Greek government formed in October 1981 by the Panhellenic Socialist Party (PASOK) conducted its own foreign policy and had little regard for coordinated EU positions.

In the second half of the 1980s, the degree of agreement among the EU countries rose again, with the Greek government moving closer to the mainstream. When Portugal and Spain became members in 1986, they had already partly adjusted to EU positions. The percentage of consensus votes among the then 12 member states continued to hover at around 45 percent. From 1990 onward, there was a steady increase in identical votes in the General Assembly, a trend that was maintained following the entry of Austria, Finland and Sweden in 1995.

This greater cohesion can be attributed firstly to the end of the Cold War, which removed the tricky issue of how to deal with the Soviet Union and its allies. Secondly, and more importantly, the Maastricht Treaty of December, 1991 replaced the looser European Political Cooperation of the 1970s and 1980s with the more ambitious CFSP. In 1998, the EU countries voted identically in 82 percent of recorded votes, nearly double the 42 percent achieved in 1990. Since then, the figure has decreased slightly to about 75 percent.

Within this overall trend, however, voting patterns have varied considerably according to the issue at stake. In voting on the Middle East, for instance, the EU states have displayed a relatively high level of consensus. Cohesion in this area has always been above average, reaching a perfect score of 100 percent in the late 1990s. There were disagreements in 2001 and 2002, but only on one or two votes. The EU countries have thus come closer to speaking with one voice since the Venice Declaration of 1980, when they decided to establish their own position on the Middle East conflict, in contrast to that of the United States. The EU countries have also achieved above average consensus on human rights issues.

There is less agreement, however, on external security matters. This should not be a total surprise, as the European Union includes two nuclear powers alongside four neutral/non-allied countries (Austria, Finland, Ireland and Sweden), of which Finland and Sweden strongly favor nuclear disarmament. Also contentious are the relatively few UN votes on de-colonization, with the United Kingdom and France, as former major colonial powers, voting differently from other EU members.

The mid-1980s saw the emergence of a "core" group of countries that usually vote identically in the Assembly. Five of the six EU founding members - Belgium, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands (i.e. all except France) - belong to this group. Since Portugal joined in 1986, it has also mostly voted the same way as the "core" countries.

Denmark and Spain moved closer to the mainstream in the early 1990s, and Greece followed in the mid-1990s. Non-aligned Finland has been very close to the core since the late 1990s. The other neutrals - Austria, Sweden and particularly Ireland - have exhibited noticeably different voting behavior. But the United Kingdom and France have diverged most clearly from the EU majority in General Assembly voting.

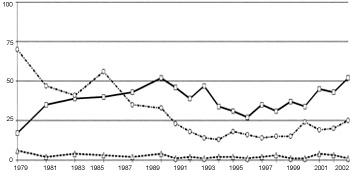

The voting figures can also be used to calculate distances between the positions of countries or groups of countries. For the purposes of this article, a "distance index" has been constructed to show the extent to which three countries, the United States, Canada and Russia, have voted similarly to or differently from the European Union. I have taken only those votes in which all EU member states voted the same way, i.e. EU consensus votes. If another country voted identically to the EU consensus, the distance is defined as zero; if the other country abstained, and the European Union voted Yes or No (or vice versa), the score is counted as 0.5. It rises to 1.0 if the country voted Yes and the European Union voted No (or vice versa). These numbers were added for each General Assembly session.

To allow a comparison over time (given that each session has a different number of recorded votes), the maximum distance is indexed at 100, a figure that would apply if the European Union and the country in question always voted as differently as possible. The minimum distance is zero, which would mean that the European Union and the other country always voted identically.

Graph 1 shows the distance indices for the United States, Canada and Russia (formerly the Soviet Union) since 1979. In that year, the United States, with an index value of 17, was not far away from the EU consensus. But the distance increased steadily during the 1980s, reaching 52 in 1989. The gap narrowed in the 1990s, particularly during the early years of the Clinton administration. After 1999, the distance widened again, with the index rising to 52 again in 2002.

In contrast to the United States, the Soviet Union was far from the EU consensus in 1979, with an index value of 70. The distance narrowed, however, especially after 1985, and the EU-Russia gap reached its lowest point in 1993, with a value of only 13. Since 1999, the distance between Russia and the EU consensus has increased again, to 25 in 2002.

Canada has always voted very similarly to the EU consensus. The overall pattern has remained much the same since 1989, with the United States voting rather differently from the EU consensus, Canada voting almost identically and Russia somewhere in between.

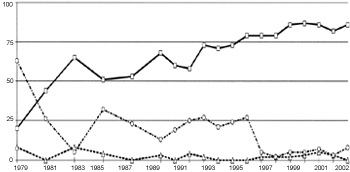

Graphs 2 and 3 show voting behavior on two specific issues, the Middle East and external security. On the Middle East, except for 1979 and 1981, the distance of the United States from the EU consensus has always been above 50 index points; since 1995 it has been more than 75 points. The Soviet Union and then Russia have narrowed the gap with the European Union over time, with Russia moving close to the EU position in 1996 and staying there. Canada is again very close to the EU consensus.

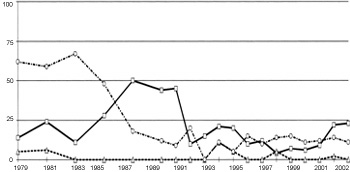

The picture is completely different when it comes to external security. As Graph 3 shows, the United States was quite close to the European Union until the mid-1980s. It then moved away, before narrowing the gap again in 1991. Since then, the United States voted similarly to the European Union until 2001, when the distance grew again.

As could be expected, the EU countries and the Soviet Union voted very differently during the Cold War. Since 1987, however, Moscow and the European Union have stayed relatively close to each other. During the Clinton administration, the EU consensus was closer to the United States than to Russia, but in the first two years of the Bush administration it moved away from the United States and nearer to Russia. Canada's votes on international security matters were mostly identical to those of the European Union.

On human rights questions, the United States used to be close to the EU consensus, but moved away in 2001 and 2002; Russia has always been quite distant from the European Union in this field. In the few votes on de-colonization in which the EU countries voted identically, the distance between the European Union and the United States has been rather big, whereas Russia has been much closer (cf. also Table 1). In both areas, Canada has again been very close to the EU consensus.

The data presented here demonstrate that the main bone of contention between the EU consensus and the United States has been the Middle East. On this issue, the distance between Europe and the United States was already quite large in the 1980s, and it has increased further since then. On other issues, especially international security and human rights, the differences have been much smaller, although the distance increased in 2001 and 2002.

Using the consensus votes of the EU member states for calculating the distance between the European Union and other countries has two drawbacks. First, the calculation does not take all recorded votes in the General Assembly into account, and, second, it does not distinguish among the EU countries. Table 1 turns the calculation around and shows the distance of the United States from each of the EU member states. We see that in 2002 the United States had a distance index value of more than 50 with regard to all EU countries, except for the United Kingdom and France, which were noticeably closer to the United States. At the other end of the scale, the EU member farthest from the United States was Ireland, followed by Sweden and Austria.

The table shows the large and nearly uniform distance of the EU countries from the United States on Middle East issues. Distances between the EU countries and the United States on international security problems are more varied. With a distance index of 22, the United Kingdom and France are relatively close to the United States. In contrast, the neutral EU members are much further away. The distance index for Ireland (45) is more than twice the figure for the European Union's two nuclear powers, and Sweden, Austria and Finland are close behind Ireland.

In de-colonization matters, the United Kingdom and France are again closer to the United States than the rest of the EU member states. In the field of human rights, the distances from the United States are below the average for all topics, and the figures are very similar for all EU members, although the Netherlands is a little closer to the United States.

If the cohesion of the EU member states in the General Assembly is a valid indicator of the development of the CFSP, then one must conclude that the CFSP made considerable steps forward in the 1990s. But the data presented here also show some of the remaining problems of the CFSP. Consensus among the EU countries is not perfect, covering only about three-quarters of the recorded votes. The United Kingdom and France are the "outsiders" among the EU member states.

The broad EU consensus on the Middle East does not necessarily mean that a united European Union can wield great influence in this area. On the contrary, at times it seems that the arduous search for consensus prevents the European Union from being more pro-active in international affairs. When the European Union finally reaches a consensus, its position is sometimes so rigid that it cannot negotiate with third countries - any attempt to change the EU position would ruin the hard-won compromise among the member states.

In the General Assembly, the European Union is often in an intermediate position between the United States and the developing countries, and the United Nations still needs the cooperation of the United States if it wants to be effective in international affairs. This means that the European Union and its member states will have to continue to try to engage the United States in the work of the United Nations. But the compromises that this will require - among the EU member states and with the United States - will probably prove hard to achieve.

Graph 1

Distance of the United States, Canada and Russia from the EU Consensus: All Votes

(Maximum Distance from the EU Consensus = 100, Minimum = 0)

![]()

Notes: * 1996 EU without Greece (Greece was absent for more than a third of the votes); ** until 31 December 2002.

Graph 2

Distance of the United States, Canada and Russia from the EU Consensus: Middle East

(Maximum Distance from the EU Consensus = 100, Minimum = 0)

![]()

Notes: * 1996 EU without Greece (Greece was absent for more than a third of the votes); ** until 31 December 2002.

Graph 3

Distance of the United States, Canada and Russia from the EU Consensus: External Security

(Maximum Distance from the EU Consensus = 100, Minimum = 0)

![]()

Notes: * 1996 EU without Greece (Greece was absent for more than a third of the votes); ** until 31 December 2002.

Paul Luif has been a member of the scientific staff of the Austrian Institute for International Affairs in Vienna since 1980, where he is responsible for the EU, in particular for defense and foreign policy issues. He is a lecturer at the Universities of Vienna and Salzburg. He has published papers on neutrality/non-alignment in Europe, foreign policies of small states, European integration, EU enlargement and the EU Common Foreign and Security Policy.