CIAO DATE: 12/07

Growing the State Department and the Foreign Service: The Powell Way

Ruth A. Davis

Full Text

Ruth A. Davis

Director General of the Foreign Service and Director of Human Resources

In response to the invitation extended by Ambassador Ogden Reid, I want to use this opportunity to update the Council of American Ambassadors on what we have been up to at the Department recently.

Because I am writing to a group of former Ambassadors, I don’t think I have to go on and on about some of the problems that have bedeviled the State Department over the past few years—inadequate funding for international affairs, not enough people to do jobs and train for jobs at the same time, and the lack of management and leadership training for our people.

So what has changed over the past 20 months or so? Quite a bit, I am proud to say.

When Secretary Powell arrived at the State Department in January 2001, he took a hard look at our “corporate balance sheet.” He compared our missions to our resources.

He concluded that the State Department’s resources—in terms of its people, its buildings, and its information management—were all inadequate to meet the diplomatic challenges that we faced. On the people front, he determined that the State Department needed nearly 1,200 more people above attrition in order to meet our present (or reasonably foreseeable) diplomatic challenges, create a training float, provide mandatory training throughout a career for our officers, and make a really strong push for greater diversity in the Department and the Foreign Service.

He therefore launched his “Diplomatic Readiness Initiative” (DRI) to set things on a new course, and used his tremendous contacts and credibility on Capitol Hill to make the case for this Initiative. Congress responded by approving Year I of this three-year project, providing approximately $100 million for it.

For those of you who might think that 1,200 is a pretty small number, let me hasten to add that this represents the largest expansion of the Department and the Foreign Service in over thirty years—since the Vietnam War, to be exact. It certainly is the biggest expansion in my professional lifetime.

I think the numbers can do some of the talking for me here. In Fiscal Year 2001 (October 1, 2000 to September 30, 2001), the Department of State hired roughly 1,000 persons—Foreign Service and Civil Service, in all employment categories.

In Fiscal Year 2002 (October 1, 2001 to September 30, 2002), the Department hired close to 1,800!

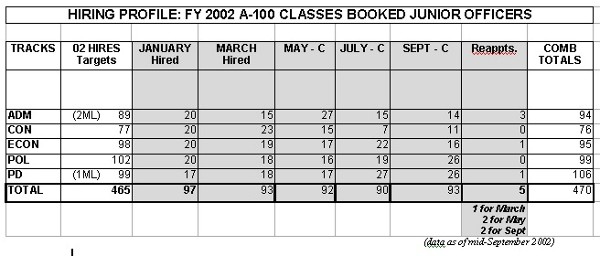

In FY 2002 we set as our goal to hire 267 more Foreign Service generalists above attrition. I am very glad to report to you that we have achieved this goal, and that the 470 Junior Officers hired in FY 2002 is a record.

I think Chart 1 at the bottom of the page gives you some idea of the magnitude of the change:

We had never had five consecutive classes with more than 90 new junior officers. Quite frankly, if you want to see the full impact of the change all you have to do is visit the George P. Shultz National Foreign Affairs Training Center at lunchtime. Change is definitely visible in the cafeteria.

The difference between FY 2001 and FY 2002 can be described in one short word: “resources.” We have had the resources we needed to recruit, examine, screen, hire, and begin to train the new talent that America needs to remain at the forefront of foreign affairs.

We are not planning to slow the pace in Fiscal Year 2003, either. We are raising the bar from the 470 Junior Officers hired in FY 2002 to our new target of 514 for FY 2003. To do this, we will hold six Junior Officer orientation classes instead of five, which will allow us to reduce average class size a bit while still managing our record intake level. I hope you will see this from Chart 2 at the bottom of the page.

In a “bottom-up” organization like ours, we realize that recruitment is the name of the game. We are therefore concentrating on this aspect of our work as never before.

The first problem that we confronted was that the process took too long. It was taking as much as 27 months from the time of exam to the time people were hired. That was simply unacceptable to Secretary Powell. We overhauled the system, and I am very happy to report that we have now gotten it down to around ten months, with a goal of pushing it even lower. That will make us competitive with other parts of the government dealing with foreign affairs and national security.

Secretary Powell also made it clear that he wants the Foreign Service and State Department as a whole to look more like America when it is representing America to the world. Our recruitment has therefore made a concerted—and adequately funded—effort to reach and attract minority candidates.

We have tackled the problem by putting more recruiters in schools with large minority populations. We have more resources for advertising in media, which reaches minorities. We have set in motion a Recruiter Emeritus program under which retired officers—or friends of the Department like yourselves—can volunteer to go out and help us find and attract top talent.

The numbers of those who have signed up for the Foreign Service Exam have soared over the last 14 months. This is in part because we made it easier for people to sign up for the Foreign Service Exam, but I believe it is also being driven by the surge in patriotism and the desire to serve that followed the terrorist attacks of last September 11.

We are developing our corps of Pickering Fellows, and we have also attracted one of the largest groups of Presidential Management Interns in the Federal Government.

All of this is the good news. But I don’t want to sound like we’ve slain every dragon and accomplished every task. Far from it. Our figures for minorities in the State Department and the Foreign Service still leave much to be desired. The total percentage of minorities in the Foreign Service is only around 14 percent, at a time when minorities’ representation in the national civilian workforce is considerably larger. Hispanics, for example, make up only four percent of the Foreign Service.

Moreover, we still have two more years of work ahead of us on the Diplomatic Readiness Initiative. We face demands for more language experts, area studies and tradecraft development, and leadership and management training like never before.

It should come as no surprise to anyone that there exists an intense demand for officers who are trained and competent in hard languages. For example, in FY 2002, we had planned to train four people in Urdu. September 11, 2001, changed things dramatically, of course, and our number nearly tripled, to 11. You can see some of this same trend line in Arabic. In FY 2001 we put 55 students through the Washington-based Arabic program. In FY 2002 we were able to ratchet that number up to 108 students.

The numbers tell only a part of the story, however. The Department needs, and is developing, an integrated collaborative strategy—a strategy designed to give earlier, longer, and deeper training in language and culture, to allow our representatives overseas to assert and defend US interests in every region of the world. Taking Arabic again as an example, the Diplomatic Readiness Initiative is making it possible for more junior officers to study Arabic for longer durations of training at an earlier stage in their careers.

This new strategy of earlier exposure to Arabic establishes a mechanism for us to build for the long term, for what we want is more “Beyond-3” speakers, who can deal with greater levels of complexity and depth in the language. By getting officers earlier in their careers, and giving them longer training at the outset, both of which are now possible under the DRI, we can produce officers with a deeper understanding of the region’s culture and values, and give officers incentives to do repeat tours in the region. To this end, the Department and the Foreign Service Institute (FSI) are actively engaged in establishing relationships with educational institutions in the region, to link them with our posts in the Arabic-speaking world and our training facilities here and abroad.

We therefore cannot afford to declare victory or slack off when we are just a third of the way through the race. But we are showing—to the Congress, to the American people, and to ourselves—that we can be good stewards of the vital infusion of resources that we have been given, and that we can produce results.

In sum, I think you can see that this is a very exciting time to be in the Department of State and involved with American diplomacy, and I close by asking for your continued active support for the Department, its resourcing, and its work for America.

IMAGE GALLERY

Chart 1