|

|

|

|

Letter from Niger, October 2003

By J.R. Bullington

*

This journal has had the distinct pleasure of publishing Amb. Bullington's missives from Niamey for more than three years. They present not only a fascinating picture of that far-away city and land, but also an accurate portrait of how many American live abroad, representing their country as volunteers and Peace Corps officials, and as plain American citizens. Following is the latest in this valuable series of reports. —Ed.

Niger, Lush and Green

|

| The swollen Niger River at Gaya, where it forms the border with Benin. Note the old bridge at right, almost under water. |

We returned from a lengthy and pleasant home leave to the greenest Niger we have yet experienced. The rainy season began in May, a few weeks earlier than normal, and the rains were abundant throughout the summer, ending about on schedule in late September. Records indicate this has been the wettest rainy season in about three decades. The semi-arid zone in the southern third of the country, where almost all of the people live, has become almost lush with greenery, and grass has appeared far north into the Sahara. Farmers are harvesting an excellent crop of millet and other grains, and the nomadic pastoralists have found ample pastures for their herds.

In some areas along the Niger River, local flooding has been a problem. The river's flow at Niamey was measured at the highest rate since record keeping began in 1928. (Unfortunately, this high flow rate is indicative not only of abundant rain but also of denuded and degraded land that doesn't retain as much water as before.)

Minister Jim and Alabama Memories

|

One of the more interesting events during home leave was going to church with my brother Mike. As far as I can recall, this was the first time I've been inside a church in more than 40 years except for weddings, funerals and sightseeing.

No, I've not been "born again," and I remain deeply non-religious; but this particular church, it seemed to me, was not to be missed, since I was publicly advertised as its Minister! Moreover, it is located about half a mile from where Mike lives, near Braselton, Georgia, right on the highway leading to his home. And since Mike and I were raised in the Church of Christ, it evoked a good deal of nostalgia.

My namesake turned out to be a fairly close relative who hails from Athens, Alabama, where I spent several years as a youngster on my grandfather's 40-acre cotton farm. Minister Jim's grandfather and my grandfather were brothers.

Mike and I weren't familiar with any of the songs in the service, as a new taste in hymns seems to have prevailed even in the highly conservative Church of Christ. The sermon, however, on "Serving God with Zeal," had some familiar notes, including the story of how the Israelites, prompted by the evil Balaam, had joined the Moabites in idolatry and fornication, and how the zealous Phineas heeded God's righteous injunction to slay all the sinners.

A real blast from the past!

Another rich trip through Alabama memories came on a flight from Washington to Atlanta, when Tuy-Cam and I were seated next to Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions. He was very friendly, and he impressed me favorably by traveling in coach without any staff. He seemed genuinely interested in Africa and Peace Corps, and I took the occasion to tell him my views on some of the continent's problems and opportunities as well as to lobby for the Peace Corps budget increases requested by President Bush (to which he seemed favorably disposed).

After we had exhausted Africa and Peace Corps as topics of conversation, we turned to Alabama, particularly the turbulent 1960s when we were both in college there. (He went to Birmingham Southern; I went to Auburn.) Since it turned out that he knows the man well, I couldn't resist telling him my John Patterson story.

Patterson defeated George Wallace for Governor of Alabama the first time George ran for the office because, as George famously put it in his post-election analysis, "He out-niggered me." During Patterson's term of office, I became editor of the Auburn student newspaper, The Plainsman, and soon thereafter wrote a front-page editorial condemning segregation and calling for Auburn's integration.

Though it sounds rather anodyne today, in Alabama in 1961 this was truly radical. In fact, so far as I have been able to determine, I was the first editor of a state university student newspaper in the deep South (and certainly in Alabama) to call for an end to segregation. The firestorm was immediate, both figuratively and literally: A cross was burned on the front yard of my fraternity house, and I was called everything from a damnyankee agitator to much worse. Governor Patterson and the state legislature threatened to cut Auburn's appropriation if it didn't put an end to such heresy, and the affair drew extensive press coverage, even in the Washington Post and the New York Times.

I somehow escaped expulsion—in fact I pretty much dared them to expel me, knowing that would almost certainly lead to a full scholarship from a more progressive university—remained editor, and continued my anti-segregation writings.

Nearly 20 years later, the State Department sent me to the Army War College for senior training. As part of the graduation festivities, the College invited a number of distinguished citizens from around the country to visit Carlisle Barracks. On the guest list for the reception to welcome them, I was astonished to see the name of former Governor John Patterson, now a leading lawyer in Montgomery. I recognized him and presented myself, saying, "Governor, you probably don't remember me, but when you were Governor of Alabama I was editor of The Plainsman over there at Auburn."

Patterson immediately drew himself back, pointed his finger at my chest, and exclaimed, "So you're the sonofabitch that wrote that editorial!"

I was proud to acknowledge that I was indeed that sonofabitch and was enormously pleased that he had remembered the editorial all those years.

Senator Sessions enjoyed the story.

The Poverty Index

In spite of the excellent harvest now underway, poverty is never far from our minds in Niger.

The United Nations Development Program releases an annual survey called the Human Development Index, also known as the "poverty index." It seeks to measure the degree of development of all the countries in the world by combining per capita income with several health and social indicators such as life expectancy, literacy, etc.

On this year's index, released in August, Niger again ranks next to the bottom, 174 out of 175. It's ahead only of war-torn Sierra Leone.

Here are some of the grim statistics from that report, with the comparable U.S. figures for reference.

| Niger | U.S. | |

| Per capita GDP | $175 | $35,277 |

| % Population living on less than $1 per day | 61.4 | 0 |

| % Population living on less than $2 per day | 85.3 | 0 |

| Life expectancy | 45.6 | 76.9 |

| % Adult literacy | 16.5 | 95.1 |

| Doctors per 100,000 people | 4 | 276 |

| Children per woman | 8.0* | 2.1 |

| % Population growth rate | 3.6** | 1.0 |

| % Urban population | 21.0 | 77.4 |

| % Population under 15 | 49.9 | 21.7 |

| % Population over 65 | 2.0 | 12.3 |

| % Children malnourished | 40 | 1 |

| % Children in primary education | 30 | 98 |

| % Children in secondary education | 5 | 88 |

|

* Highest in the world |

||

There are other figures just as depressing, such as the fact that three of every 10 children born in Niger will not live to see their fifth birthday. Moreover, the high rate of population growth assures that extreme poverty is likely to persist for the foreseeable future.

These are the difficult realities that our Peace Corps Volunteers must live with on a daily basis.

Volunteer Village Life

|

| Iris, center, with Tuy-Cam, left, a Peace Corps driver, and other Volunteers. Tuy-Cam and I were visiting and had brought them a picnic lunch. |

Iris Flannery completed training and was posted to her village last March. She has been writing accounts of her life in the village for her hometown newspaper, The Humboldt Beacon of Fortuna, California. Following are some excerpts.

For the past month I have been settling into the village where I will be living for the next two years: Bangario Moussa. It has a population of 500 ethnic Zarmas. I live in a round mud-brick hut, which has a woven grass/millet-stalk roof. I have an outdoor latrine, and a cement slab for a shower. Obviously, I don't have electricity, plumbing or running water. My hut is surrounded by a millet-stalk fence. It keeps the roaming donkeys, cattle, goats, sheep and fowl from sneaking in and damaging my tree nursery or my garden.

My biggest adjustment has been pulling my own well water. My hut is 50 feet away from the nearest well. I pull my water with a rubber bag (made from recycled inner tubes) on the end of a 16-foot rope. Two bags fill my plastic bucket. Then I carry the bucket on top of my head back to my hut. I am very proud of my newly acquired ability to carry water on my head. I can even use only one hand to steady it! I use at least four buckets of water a day.

Jason Chau at his hut, a typical Zarma house similar to the one Iris lives in. Last Friday the rains fell for the first time in Bangario Moussa, and on Saturday I went out with the mayor's family to plant their fields. We set out at seven o'clock, Fatiya-nya, the mayor's wife, and her grandsons: Brahaminu, 11; Almagidi, 9; Abdul-baki, 7; and myself.

Fatiya-nya led the way at a fast pace on the sandy path carrying her water kettle and several small calabashes on top of her head. Abdul-baki, despite being the littlest, followed close behind, with Almagidi and I chatting, and Brahaminu, who was carrying the heavy bag of millet seed on his head, trailing behind.

The walk out to the field took over an hour. The men of the household, the mayor and his grown son, had left the village earlier and were already out cultivating.

We arrived at the mayor's field, where the mayor and his son had already dug shallow holes covering an acre in the hour or so they had been working. The fieldwork, like most village labor, is divided along lines of age and gender, with the men cultivating the fields and the women and children planting the millet. Fatiya-nya gave the boys and me each a calabash of millet seed. We went up and down rows, dropping a pinch of seeds into each hole, then stomping the sand back over the top.

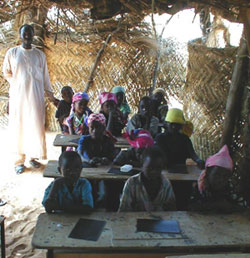

My village is lucky enough to have its very own schoolhouse. It is one room, full of wooden desks and benches, and has two blackboards. It is the only cement building in the village. (All others are built from mud bricks.) There are 130 students, from Bangario Moussa and a couple of other nearby villages. The one room can hold only so many students; the remainder is taught by a second teacher under an adjoining millet-stalk shelter. There are 78 boys and 52 girls.

On Wednesday I spent the morning sitting in school. The teacher, Bagio, wrote a short paragraph on the front blackboard in French, which turned out to be a math problem about the cost of soccer balls. Each student copied the paragraph carefully on his or her handheld blackboard, while Bagio sat at his desk. As the students finished, they brought their work to Bagio, who corrected it. After all the work had been checked, two hours after we had begun, the class ended for lunch break.

School kids and their teacher For me, it was a tedious and boring two hours. I was impressed by how attentive and hardworking all the students were. Still, in a paragraph of 15 French words, there was not much learning of vocabulary, grammar or syntax. And since my village children are just as likely to greet me with "Bonjour, Monsieur" as with "Bonjour Madame," I do not think they are learning much French.

With eight national languages, the Nigerien government has chosen French as the official language. In this way, none of the ethnic groups is being favored over others. However, learning arithmetic, reading and writing in French rather than one's native language is very challenging, especially because the students do not come in regular contact with French outside the school. Only the brightest, most dedicated and most encouraged students attain sufficient proficiency to go on to secondary school.

The Yellowcake Road

Niger has gained unaccustomed notice in the American and world media because of uranium, Joe Wilson, and an incredible chain of events that has propelled what seemed a rather minor story to the heart of U.S. politics.

I have been totally, and happily, uninvolved; and locally the affair has been given very little press or public attention. Joe was my deputy when I was Ambassador to Burundi, so when he visited Niamey a few months ago we had him to lunch and dinner. Quite properly, he said nothing to me about his mission to check out an intelligence report that Iraq had tried to buy uranium from Niger. (It is longstanding U.S. policy that Peace Corps should in no way be connected with intelligence work.)

Readers might be interested in some basic facts about Niger's uranium industry that are publicly known and have been reported, most notably in a recent series of articles by Associated Press writer Bruce Stanley, who visited Niger in September. (I don't think his articles were widely published in the U.S.)

Niger has been producing lightly processed uranium, called yellowcake, since the 1960s. It comes from two mines located in the vicinity of Arlit, an oasis town far north into the Sahara near Niger's borders with Mali and Algeria. The mines are jointly owned by the Nigerien government, a French government-owned company, a state-owned Spanish company, and a private Japanese consortium. These owners are the mines' only customers.

Although it is the raw material for enriched uranium that can be used as nuclear reactor fuel (or to make an atomic bomb), yellowcake is low in radioactivity and poses a health risk only if ingested. This bright yellow, powdery material is loaded in thousand-pound drums at the mines and hauled on flatbed trucks from Arlit to Agadez and thence south through Niger and down the length of Benin to the port of Cotonou, whence it is exported to Europe and Japan for further processing and use in nuclear power plants. (In driving along this road, I have frequently seen small spills of yellowcake brightening the desert roadside.)

Niger exports about 3000 tons of yellowcake annually, which account for two-thirds of its approximately $300 million a year in export earnings. It is the number three producer of yellowcake worldwide, after Canada and Australia.

Because of its low radioactivity (and hence unsuitability for use in a "dirty bomb"), and because a very large quantity (about 9000 pounds) would be required to yield enough enriched uranium for a bomb, Niger's yellowcake has not been considered a very high security risk. In the post-9/11 environment, however, there have been suggestions that additional security and accountability measures may be appropriate.

According to the Associated Press, "If Niger wanted to sell yellowcake independently, experts say, the government would almost certainly need its foreign partners' consent. What's more, any clandestine sale probably wouldn't generate a financial windfall for the government. World uranium prices have fallen continuously for years, and Niger's mining companies are struggling to break even, given their relatively high production costs."

I leave to the gentle reader all speculation as to how Niger's uranium could have led to the story currently dominating U.S. news media and political discourse.

The Road to Accra

This year's conference of African Peace Corps Country Directors was held in September in Accra, Ghana. When I discovered that it would take three days to fly there, with plane changes and overnight stays in both Dakar and Abidjan, I decided to go by road instead. It would take about as much time, but there would be less risk of being stranded by flight problems and changes (frequent among African regional carriers), and it would be more interesting to see the countryside along the way instead of airports.

So Tuy-Cam and I set out in one of the Peace Corps Toyota Land Cruisers with a Peace Corps driver who knew the way. We spend the first night in Parakou, in central Benin, and drove on to Cotonou the next day.

|

|

| Pool at La Palm hotel, Accra | Tuy-Cam shopping for avocados in Togo |

We were especially interested in seeing Cotonou, since we had served at the Embassy there more than 20 years ago. We found it to be greatly changed, and not for the better, at least in quality of life. When we were there, the government was nasty, but the city itself was quiet and rather pleasant. Now, it has grown so rapidly that it has outstripped its infrastructure. It is dirty and crowded, traffic is permanently snarled, and, as Tuy-Cam remarked, the people don't smile any more. The change has been so great that we had a hard time finding the Ambassador's residence—the house where we lived for over two years—and when we did find it we were chased away by the guards.

We decided not to spend any more time than necessary in Cotonou, and continued on across Togo to Accra.

This was our first visit to Ghana. (When we were in Benin, 1980-82, Ghana was in the throes of revolution and civil war, and travel there was not recommended.) We found Accra to be considerably more developed and prosperous than Niamey, and a bit more orderly than Cotonou. The conference hotel was on the sea, and was truly first class by international standards (though it did give me my first case of acute diarrhea during the last three years of living in Africa).

On the way back, we spent the first night in Lomé, the capital of Togo, a city we visited fairly frequently while assigned to Benin. Tuy-Cam had brought along a couple of coolers, which we filled with red snapper, shrimp and squid to take back to Niamey, where seafood is hard to find. We also bought avocados, pineapples and other fruit. After another overnight stop in Parakou, where we stayed in a reasonably good hotel run by an expatriate Frenchwoman, we arrived in Niamey exhausted and genuinely happy to be back home.

Note *: J.R. Bullington is currently Country Director of the Peace Corps program in Niger. He was formerly a US Ambassador and career diplomat, with extensive service in Africa and Asia. Back