|

|

|

|

CIAO DATE: 9/00

State Strength and the European Union: Examining the Impact of Unification on Europe’s Major Powers

Timothy Ponce

International Studies Association

41st Annual Convention

Los Angeles, CA

March 14-18, 2000

Abstract

The continued drive to unify Europe holds numerous implications for the measurement of state strength. The emergence of the European Union as a powerful player in the post-Cold War international system still remains to be seen. This article examines the complications for state strength brought about by European unification. Particularly, I examine the impact of unification on state strength for the United Kingdom, France, Germany and Italy from 1960 to the current period. Although potentially construed as part of the pains and process of unification, this paper argues that European unification does not seriously erode the strength of these states. My results indicate that these more powerful states are influenced negatively by the processes of globalization but not regional integration.

As we end one century and look to begin a new one, many questions arise as to role of the state in the international system. For better part of the 20th century, scholars of international politics and political science have largely regarded the state as the dominant actor in the international system. However, during the last half of this century, the nature of relationships between states changed as new influences and actors entered the system. There are roughly four times as many smaller states in the international system. State strength is no longer solely weighed in terms of military strength and the acquisition of territory. States and their citizens compete to acquire market share and are not focused on colonial acquisition or territorial domination as a way to acquire rights to resources. International organizations, multi- and transnational corporations and a variety of foreign markets place limits on the ability of the state to pursue policy. At the end of the 20th century, states are increasingly confronted with problems related to the relationship between the domestic and global economy.

A second important event during the latter half of the 20th century concerns Western Europe. The European continent has long been a battleground for states and regional actors. Not only has world war originated from Europe but also the modern conceptualization of the state. The definition of the modern state and its foremost rights to sovereignty emerged from Europe with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. This historic agreement set the foundations for modern government as well as relations between states. Over the course of three hundred years, states frequently battled with one another, finally culminating in World Wars One and Two, which brought major destruction to most of Western Europe. In order to rebuild the Western European states effected by these wars, their leaders, with encouragement from the United States, sought regional integration as a path to redevelopment. Regional integration did serve to lift Europe from the wreckage of World War Two, but most would concede that this was in relation to economic affairs only. However, the member-states of the European Union have gone beyond the boundaries economic integration and adopted a Common Foreign and Security Policy and a Social Charter as well as building a European Court of Justice that has become a strong legal actor. Given the historical nature of relationships between states, these developments would seem to compromise many of these states rights to sovereignty and decision making. Thus, proceeding with regional integration to this degree poses to weaken their strength to act not only in the international system but in relation to their domestic polities and economies as well.

But will it? These same states have also struggled in implementing and agreeing to the Social Charter, and the Common Foreign and Security Policy is largely regarded as a sham. Overcoming the well-defined national, cultural and linguistic character of the modern European nation-state seems to be a rather large stretch of the imagination. What would possess these states to throw away hundreds of years of history? However, given an increasingly uncertain global economic future and unwillingness of the United States to take decisive control in these matters, a strong, unified European actor or state may be a path to greater systemic stability and structure. Furthermore, the possible emergence of a unified European actor in international relations bears many interesting questions as to the distribution of power within the international system as well as to possible fate of the modern nation-state under the influences of regional integration and globalization.

Conceptualizing State Strength

Scholars in political science and international studies have given much attention to the concept of state strength. So much so that is has become difficult to determine a consistent definition of state strength. Then why is it so important that we continue to study state strength despite an apparent inability to arrive at a common conceptual consensus? As Jacek Kugler and Marina Arbetman so aptly put it, the study of state strength is important because it enables academics and national leaders to estimate the strengths and weaknesses of a state and of that state’s opponents (1989, 91). Doing so affords state decision-makers preparation for potential conflict situations, whether economic, political or military. Additionally, information on state strength allows statesmen and citizenry to assess the performance of government, its losses and gains relative to other governments and international influences and the opportunity to adjust either its policies or its attitudes to either a new higher or lower status in international affairs.

In examining the literature on state strength, there are two important dichotomies. First, there are two notions of strength: structural and relational. Structural strength refers to the ability of a state or states to define and set the boundaries and parameters for the conduct of politics in the global system. (Caporaso and Haggard 1989, Ruggie 1989, Strange 1989) States that hold structural strength hold the ability to determine a great majority of outcomes in international politics. They have played a primary role in initiating and shaping international organizations and setting the rules by which multinational and transnational corporations are governed. Since the end of World War Two, this role has been largely occupied by the United States, who played a fundamental role in begetting the United Nations and its predecessor the League of Nations and also in shaping many of the economic and political institutions in rebuilding Europe and Japan. In regards to international economics, the United States financial markets, corporations, currency and government treasury play an overwhelmingly strong hand in determining economic outcomes. Regardless of whether or not its strength in relation to other states declines, the United States, and for that matter any other state who exercises predominant structural strength, will dominate the international system via the favored position it has created for itself. (Strange 1987, Ward 1989, Strange 1991, Reuveny and Thompson 1997)

However, the concept of relational strength, as I set out earlier, is of great importance to states, their leaders and academics. I admit that structural strength is a more ‘powerful’ concept because it refers to the ability of one actor to determine the rules for all other actors. But how does it change? Typically, most explanations have revolved around the occurrence of global war and the systemic transition from one hegemonic leader to another. (Modelski 1978, Thompson and Rasler 1988, Levy 1991, and Volgy and Mayhall 1995) However, within the logic undergirding most of these theories, one can find the importance of the strength states hold in relation to one another. The logic of relational strength holds that those states that possess more and are better able to use their resources are to be considered the more powerful states. (Organski and Kugler 1980, Kugler and Domke 1986, Kugler and Arbetman 1989, and Krasner 1994) While war is a means by which one state can satisfy its perception that it is stronger over another, it is the belief that it is in some way, whether militarily, economically or diplomatically, superior to its potential adversary that motivates a state toward action. Within the Within the study of both structural and relational strength, there is a further dichotomy as to the dichotomy between relational and structural strength, it is with relational strength and the ability of the state to withstand influence that I am most concerned.

Within the study of both structural and relational strength, there is a further dichotomy as to the resources of state strength versus the capacity of the state to control and employ these resources. While the differences between structural and relational strength are important to developing an understanding of international politics, the concept of state capacity supersedes debate of these two concepts. In relation to state strength, state capacity refers to the ability of the state to use its resources and influence outcomes, regardless of the levels of those resources. This means that states weaker in resource terms may actually be better equipped organizationally, structurally or managerially to deal with certain policies or problems. Thus, they may actually be stronger than states that possess a greater abundance of a particular resource.

In assessing state capacity, state structure is of foremost importance. The determinants of state structure continue to be hotly debated among and between comparative and international politics scholars. Primarily, analysis of the literature on this matter breaks down into three influences: global, society and the state itself. The scholars positing global influences as determinants of state structure focus on the influence of international actors, on relational strength between states and to the precedence of historical economic development between states (Wallerstein 1974, Keohane and Nye 1997a, 1998 and Keohane 1998). Conversely, scholars posing historical societal influences look to the historical development of the relationships between classes, elites and other social groups (Moore 1966, Jackman 1974, and Rueschemeyer, Stephens and Stephens 1992). Finally, there are those scholars focused on the role of the state, which, once created, becomes an explanatory variable itself, as it defines the norms, laws and institutional arrangements that govern both private and public conduct (Krasner 1976 and Skocpol 1979, 1985).

However, some scholars note that they are missing the point. Each of these three perspectives exerts an influence upon state structure and hence its capacity, as domestic and international forces interact at a multitude of levels. These scholars note that modern states must deal with and reconcile the conflicting interests and influences of all three sources (Kugler and Domke 1986, Ikenberry 1986a, 1986b and 1989, and Caparaso 1997). I concur with this perception but particularly wish to address a methodological issue dividing them. This issue concerns the comparability of influences upon the state. To some, the state is a unique product of history (Ikenberry 1986a and 1986b). The state represents a constellation of forces peculiar to that state only, making comparisons between states difficult and possible only through detailed analyses of states on certain areas of policy.

On the contrary, I feel that this issue can be resolved through careful quantitative analysis in terms of the resources of state strength by weighing international, regional and domestic influences on each state individually and collectively. Judging state strength is not easy but can be done in relation to the success governments enjoy in improving the resources at their disposal and guarding them against external influences. This conceptualization of state strength is both nuanced yet admittedly rough. It is rough in that it does not seek to assess the individual history of each state nor does it regard their particular strengths in a particular policy area. However, the state is composed of numerous policy areas, constituents and historical forces. A state’s legitimate position in international bargaining situations and arenas is not only based on its strength in the pertinent area but also in regards to its overall strength in relation to other actors. This strength is promulgated based upon the success of the state in strengthening the resources available to it, whether in directly or indirectly doing so. My conceptualization of state strength is nuanced in that it posits that certain states can be stronger based upon their ability to balance direct state control over resources with letting market forces work.

As to the resources of state strength, scholars of international politics traditionally identify three primary resources. First, military resources constitute an important concept related to the measurements of state strength. While one might be lead to believe that military strength has taken a back seat to economic strength in the post-Cold War system, it is still important. Primarily, it is important because we simply do not know how other major powers would behave if not for the United States current superiority in military affairs or in a possible United State decline in international status. Additionally, relations between current major powers (including China and Russia) seems relatively benevolent, but we can not be sure that mankind has once and for all cast off tendencies for war. To be certain, the international system is governed by an increasingly dense pattern of formal and informal treaties and agreements. However, these agreements and treaties rely on goodwill between states for their maintenance. Military strength remains the ‘means of last resort’ upon which states can rely if international goodwill breaks down.

A second resource of state strength measures the total productive capacity of a state. Many authors use Gross National Product (GNP), Gross Domestic Product or either of the two in per capita terms as indicators of economic state strength (Kugler and Domke 1986, Kugler and Arbetman 1989). In terms of addressing the strength of the state to control resources and outputs, Gross Domestic Product per Capita represents the valued output of society per member of that society. Conversely, some scholars choose to use either Gross Domestic Product or Gross National Product to measure the relational strength between states. However, in addressing the ability or capacity of the state to extract resources or be influenced by external or internal forces, it is necessary to examine economic strength in terms of the value of productive capacity per member of society. In such a case, GDP per capita is the appropriate measure that permits better cross-national comparison as it controls for population. Undeniably, if one were to use GNP or GDP to measure state strength, the United States, with a GNP roughly four times larger than the second most powerful states, Japan and Germany, estimates of state strength would be biased. GDP per capita measures the performance and value of the total economy and national resource based with both government and private sectors accounted but averaged against the members of the state. Furthermore, GDP per capita represents a parsimonious and efficient indicator, which is easy to obtain yet contains a maximum amount of information on the performance of the state in a multitude of sectors but does not react to shifts from civilian to military production.

The final conceptualizion of state strength has not been given as much attention in the literature as military and economic strength. While economic and military strength are important indicators of physical strength, it is also necessary to assess the state in terms of its diplomatic ability. Diplomatic strength represents the ability to manage conflict, problem solve, negotiate, bargain, and manage programs, cross-cultural interactions, communication and information. (Reychler 1979 and Moravcsik 1993) If the number of salient international actors is increasing at a rapid pace as globalization predicts, then the diplomatic strength of state will increasingly become an important factor. Furthermore, if interdependence theorists are correct, then increasing globalization will demand that a state be more diplomatically active and alert, as it must respond to the actions of an increasing number of important international actors. In a globalized international economic system, the state will increasingly pursue action through negotiation and bargaining, especially in its interactions with other democratic states. Thus, given a potentially diverse global society, the state must be able to effectively manage and transmit its self-interest to international as well as domestic actors and perceive and receive pertinent information to the formation of that self interest. (Putnam 1988 and Cox 1997) The ability of a state to field diplomatic corps that can represent the national interest, translate policy to other actors and report on international conditions is an important element of state strength.

In particular, I feel that there are two relative and important components to measuring state diplomatic strength. First, there is the concept of ‘soft power’ or soft strength. In terms of state strength, soft strength refers to the ability of a state to obtain its desired outcomes because other states want what it wants (Keohane and Nye 1998). Soft strength is an important measure of state strength because it represents the fundamental ability of a state to obtain outcomes through its diplomatic corps and the aid a state distributes to other states and peoples. Aid comes in many forms but is designed primarily as a financial means to tie foreign interests to a state’s own foreign and domestic agenda. This is soft strength because the ties can be formal but are most often informal as future aid is dependent upon the recipient maintaining policies satisfactory to the donor. The diplomatic corps is then responsible for the translation, release and transmission of state policy to recipients as well as to other international actors. Their ability to perform this actual is crucial, as they are responsible for informing other actors of the rewards and consequences of choosing for or against the represented state. Soft strength is necessary in the international arena, as states must rely on the skill of their diplomatic personnel to accurately spell out their state’s policies and also to warn other states of the consequences of taking action against their specified policies.

The State and Globalization

In examining the variations of state strength among major powers due to the influence of regional integration, it is first necessary to assess the impact of other international forces on state strength. Across the range of scholarship on this question, scholars are raising questions as to the ability of the traditional Westphalian state to control infractions upon its sovereignty and maintain the integrity of its dominance of its domestic affairs as well as its prominent position as the primary actor in the international system. These scholars are concerned with the increasing dominance of economic issues over political ones, the influence of transnational corporations and international organizations, and the increasing salience of transactions and decisions at the global level. These concerns are reflected within the literature of this debate over the effects of globalization on the state, of which there are primarily two schools of scholarship.

The theories of the first school concern the notion that the strength of the modern state is declining and that its predominance as the central actor in international politics is ending. Primarily, there are two fundamental bases that influence the arguments of this first school of scholarship: the effects of a growing global economy on traditional notions of sovereignty and the influences of political structure on the state. For those scholars who look to the effects of the growing global economy, the state is experiencing a serious decline in its ability and strength to regulate and react to the intensifying patterns exchange in international markets (Strange, 1987, Cox 1989, Ruggie 1989, Strange 1989, , Rosenau 1992, Strange 1994, Schwartz 1994, Strange 1995, Volgy and Mayhall 1995, Sassen 1996). The majority of these economically oriented scholars agree that the world’s financial markets are becoming increasingly unregulated, which they view as a primary cause behind the declining strength of the state.

The rapid expansion and increasing lack of regulation over credit, foreign exchange, bond and capital markets holds a number of potentially disturbing effects for state control over its own resources. First, it means that these markets are increasingly unresponsive to government economic policies and actions (Strange 1989). As the value of trade on these markets increases, states are increasingly unable to exercise power over them. Second, as these markets expand, those actors that have benefited and have some ability in interacting with them will become increasingly important and influential actors (Sassen 1996). These actors, such as transnational corporations or international financial organizations, now posses the ability to directly influence government economic policy and force governments to change, delay or scrap existing economic plans. Finally, as the saliency of international markets and economics prevails over their domestic counterparts, domestic firms are increasingly open to international competition from larger, wealthier multinational or transnational corporations (Schwartz 1994). International competitors can contract at lower prices, and when they do, national governments have less opportunity to intervene and set policy, unless international competitors violate national law, which they most often do not.

The rapid growth of technology in the latter part of the 20th century is another cause for pessimism on the strength of the state among economically minded scholars. The advent of the Internet, the personal computer and the importance of the telecommunications industry have outpaced the ability of the state regulate the development of these technologies and advancements. These technological advances are a primary force behind the internationalization of production, capital and finance and increase the likelihood that other actors will seek to compete on a state’s domestic market (Strange 1994). Subsequently, states are forced to continually invest in the latest and rapidly outdated forms of technology at great cost in order to maintain pace with the global economy and other international actors. Combined with its more traditional responsibilities in maintaining the nation, these scholars argue that the state cannot hope to keep up and produce growth in the long term.

The second perspective on the effects of globalization is grouped together by the fundamental influences that certain actors, institutions and structures hold on the sovereignty of the state (Lindblom 1977, Milward 1992, Sassen 1996, Cox 1997, Keohane and Nye 1997a, Keohane and Nye 1997b, Caporaso 1997, Lamborn 1997). These scholars can be further divided by the particular focus of their studies on the effects of globalization and an enlarged number of actors in the international system on the state. First, some of these scholars note that the state loses its pre-eminent status and ability to determine outcomes as more and diversified forms of actors emerge in the international system (Cox 1997, Keohane and Nye 1997a, 1997b, Lamborn 1997). As more actors and institutions come to hold important positions of influence on the strength of the state to control resources and outcomes, states must formulate policies that account for and react to these actors. Furthermore, as the global economy and these new actors obtain saliency and positions of structural power, the age-old realist notion of the supremacy of ‘high politics’ and military dominance have increasingly less meaning. As state abilities decrease, they become increasingly interdependent with and even dependent upon other states and these new international actors. Thus, the proliferation of multiple and competing forces makes it increasingly difficult to adopt and use a ‘state only’ perspective as to international relations (Caporaso 1997). To these scholars, new international forces and actors are bombarding the state, which cannot hope to maintain its central position in world affairs.

Other scholars pose that there are fundamental changes at national and individual levels of analysis that are pertinent to assessing the impact of globalization on state strength. While international economic forces are increasingly wrecking havoc on the state’s ability to govern its own affairs, Charles Lindblom posits that this should not be a surprise to most political scientists. Specifically, Lindblom notes that the history of democracy has been a struggle to obtain personal liberty and freedom, and the majority of these freedoms are rooted in economic liberties (1977, 163). To illustrate his point, he examines the market structures of the world’s states and finds that all democracies have market-oriented economic systems but also that not all market oriented economic systems are democracies (161-2). Democratic states are structurally geared to allow citizens to pursue their economic desires, and, as such, the increasing saliency of the global market and its power over the state is a natural development. Furthermore, Ronald Inglehart (1967) and Saskia Sassen (1996) find support for Lindblom’s assessment in the emergence of attitudes and outlooks on citizenship that are increasingly becoming more globally oriented.

The second school on globalization directly challenges the view that state strength is declining. These scholars point out that concerns over globalization are not new and have been ongoing since the inception of the modern state system with the 1648 Peace of Westphalia (Gilpin 1971, Krasner 1976, Waltz 1979, Thomson and Krasner 1989, Krasner 1994, Winters 1994, Weiss 1998). They argue that decline scholars make fundamental assumptions concerning the status of recent developments in the international system. First, decline theory assumes that recent historical developments are unique, that states had been able at some time to control transborder movements and that recent technological changes represent some fundamental long-term change in the international system (Thomson and Krasner, 197). Mercantilism and mercenarism posed unique and complicated border control problems, yet states coped with these problems and eventually controlled them. Furthermore, the development of reliable weaponry, such as the rifle and portable artillery, or other developments such as the telephone, the printing press, reliable oceanic transportation and the advent of flight were all important major technological advancements that affected international relations and global economics at past times. Thus, these scholars hold that current developments should really not be considered any more spectacular than that of past years nor should be used to make such long term structural pronouncements.

These scholars do note that decline scholars are correct in assessing growth in the level of international transactions. However, these scholars also argue that decline scholars tend to ignore a number of fundamental state achievements over the course of this century. While fluidity of capital and international transactions are increasing, transnational corporations and international organizations still rely upon the state to provide security. The security provided by the state comes in numerous forms. Fundamentally, the state sets the fundamental framework of economic activity and channels it in directions that tend to serve the objectives of dominant political groups and organizations, whether democracy or autocracy (Gilpin 1971, Krasner 1976). Couldn’t transnational actors use the competing interests of different states to secure its desires and thus exercise power over the state? Possibly, but the fact of the matter remains that transnational actors may pursue such policies in lesser developed and weaker nations but still rely upon the stable property rights and opportunities afforded by advanced states (Thomson and Krasner 1989) and also the secure channels and provision of capital and finance they provide (Winters 1994, Weiss 1998). While the international economic system may be more complex, scholars reject the decline thesis and maintain the centrality and power of the state in global politics well into the 21st century.

The European State and Regional Integration

In light of the continuing fundamental role of Europe in the modern international system, the debate over the effects of globalization on the state and its strength are particularly salient to the process of European integration. If this relationship is to be examined, then it necessary to consider the effects of regional integration in relation to both as it has played a fundamental role in the post-World War Two development and reemergence of Western European states as strong actors in the international system. Likewise, the literature on regional integration is rich with competing theoretical perspectives focused on multitude of effects of integration on Europe but has not satisfactorily dealt with its relation to state strength and the effects of globalization. Research on regional and European integration is broad as multitudes of scholars focus their theories, analyses and explanations on particular institutions, processes, political actors and policy issues. However, the focus of this research in regards to regional and European integration concerns the long-term effects and ramifications generated when states yield sovereignty to a supranational actor or institution on the status of state strength and the roles of European actors in the international system. If globalization truly represents a threat, the state must possess sufficient strength to ensure its present and future political, economical and social stability.

In considering the relationship between globalization and state strength, the role of regional integration poses an interesting question. This question concerns the effect regional integration could exert upon the state. While few would agree the surrender of sovereignty on any issue would serve to strengthen the state, regional integration may possibly serve to shield, protect and even enhance state strength. Indeed, the historical recovery of Western Europe following World War Two indicates this possibility. France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom represent strong states in the current international system and have played stronger and more dominant roles in the past. World War Two deeply diminished their strength relative to other states such as the United States and the Soviet Union yet regional integration served to protect their fragile economies and industry following the war and afforded them the ability to reemerge as influential and strong actors in international politics (Milward 1992). As strong actors in the international system, they choose to continue to pursue regional integration primarily to promote economic growth and stability, thus to promote state strength. These states also chose to further integrate at legal and political levels in order to manage previous economic arrangements as well as establish avenues and frameworks for future efforts.

The choice for regional integration in the post-war period proved a beneficial one. In the wake of the destruction of the war, Western European states desired to possess the ability to protect themselves from future conflicts and to rebuild their economies in such a manner as to ensure political and economic stability. With the aid of the United States, such regional institutions as the European Coal and Steel Community, the European Economic Community and many others were created to promote the economic recovery of Europe yet that would simultaneously prevent any future occurrence of war and conflict at the level of World War Two. The United States hoped that the political and economic integration of Europe would serve this goal. Despite indications in the Treaty of Rome towards political integration, Western Europe pursued economic integration solely as state leaders diluted the powers of European political institutions. The primary political body among regional institutions, the European Council of Ministers, could only pass decisions by unanimous vote and met every six months. While states desired integration as a path to present and future stability, political questions and matters were left specifically to state leaders, much in keeping with the prevalent theoretical perspectives of the time.

Among the major early theoretical perspectives, pluralism and functionalism dominated the debate. Concurrent with the decisions of national leaders after World War Two and during the first decade of integration, pluralism explicitly focuses its analyses on the state, which is viewed as primarily concerned with maintaining its sovereignty over decision-making (Deutsch et. al., 1957, Henig 1973, Wallace 1982 & Hoffman 1982). While integration could serve to boost economic growth and industrial productivity, the state was and remains the most fundamental unit of leadership. The destruction of Europe during World War Two demanded strong state supervision and administration of its own affairs. Economic cooperation and integration, however, was seen as a matter of low political importance. Like their realist kin, the pluralist school finds no real problem with economic cooperation provided the state maintains full control over its affairs. In line with the early processes of European integration, the goals of regional integration were the formation a community of security in hopes of preventing the recurrence of conflict and war and increasing the predictability of the behavior of all political actors (Deutsch et. al., 1957, 3-5). Sovereignty was only nominally pooled into early European institutions, which did serve to normalize social practices between states. Over time, these states came to agree that further integration would serve to supplement security issues and enhance the lines of communication between actors.

The similarity that functionalism shares with pluralism lies in the important yet contentious nature it ascribes to security and political issues. However, instead of focusing on how states deal with each other only on these issues, functionalists view integration as attainable through economic and social cooperation. These strong bonds produce the means by which predictable behavior and peace are produced in international as well as regionally integrating settings. As the social and economic bonds strength between states, functional theory posits that the satisfaction of social and economic ‘functions’ or demands at the regional level will increase as the constituents of the respective governments find it successful (Mitrany 1966, Lindberg and Scheingold 1970, and Caporaso 1974). While not targeting the replacement of the state with a regional supranational government, functional theory points to the fulfillment of non-political functions of society that exert important influences upon the political system and its functions that would lead to enhanced functioning at the regional level (Pentland 1979). Furthermore, activities and functions are organized separately and specifically according to the nature of citizen demands, which arise in response to the perceived needs or problem of the current time. The political structure is simply the sum of functions performed by the government that solve these problems or issues. For example, European Union member-states have lowered shipping tariffs amongst themselves to reduce costs for shippers and bring more goods for sale to national markets. As European consumers find increasing satisfaction in marketing their goods, they will demand of their respective governments to ensure their newfound opportunities. Therefore, regional integration is logical if it can more efficiently meet constituent demands.

However, the events of the mid-1980s through the 1990s changed many perceptions as to the validity of these theories in describing European reality. Not only did the European Community expand to fifteen members but also began once more to pursue economic, political and legal integration. The impetus for increased economic integration was the Single Europe Act (SEA), which amended the Treaty of Rome and created the Single or Common European Market. Originally proposed by the European Commission in 1979, the Single Europe Act was eventually adopted due to the failure of Keynesian economic management. The global economic crises and stagflation hit Europe hard during the 1970s, and European governments were powerless to reverse the negative impact upon their economies. Burdened by recession in the early 1980s, French, British and German politicians recognized the failure of the Keynesian school to rectify the situation. Facing pressure from the European Round Table of Industrialists and from the general private sector, governments adopted the SEA to protect their markets from the uncertainties of the global economy. Not only concerned with global crises, the private sector demanded the SEA as part of a larger European effort to provide opportunities for its larger corporations, which were feeling pressure from American and Japanese multinational corporations. Both private and public sectors viewed enhanced integration and market protection as a means to stimulate growth and their influence internationally.

In order to insure the pace of integration, governments also pursued a number of important political reforms. First, the primary decision making body of the European Community, the Council of Ministers, agreed to revert to simple or qualified majority voting in 1985. The previous voting system required near unanimity among the member-states. As the economic situation stagnated in the 1970s, this voting system often prevented the EC members from pursuing decisive policy as one member-state wielded power enough to derail any proposal. The change to simple and qualified voting procedures allows the Council of Ministers to arrive with greater frequency at decisions to assist integration. Second, the member-states took decisive steps to reduce the more subtle barriers to integration with the "Project 1992" initiative. Initially discussed in 1986, the main goal of Project 1992 was the elimination of non-tariff barriers, which were important tools states could use to defend their markets. Non-tarriff barriers (NTBs) referred to the high standards many states would set for important domestic industries: so high, in fact, that foreign countries couldn’t possibly hope to compete within the NTB protected market. Project 1992 targeted 287 instances of such NTBs among the member-states and required them to eliminate these barriers by December 1, 1992. Hopefully, if member-states complied, the goal would stimulate further movement of people, goods and capital within the Common Market. As the end of 1992 drew near, indeed, most of the targeted NTBs had been reduced to desirable levels.

In terms of legal integration, the increasing social and economic exchange between states led to an important role for the European Court of Justice (ECJ) sorting out the likewise increasing number of trade and other regional disputes. While dependent upon references from national court justices, the case load for the ECJ has steadily increased over the years to the point where it adjudicates between 160 and 200 ‘references’ or cases per year (Stone Sweet and Brunell, 1998). What is most enlightening about the role of the ECJ as an illustration of deepening European integration is the willing deference of national courts to its rulings. While not to say there has not been opposition, a clear precedent is set that grants superiority in many matters to the rulings of the ECJ and to the legislation passed by the Council of Ministers and European Parliament. Furthermore, as the court’s rulings have come into contact with an increasing segment of European society, it has been received in a favorable light (Caldeira and Gibson, 1995). The emergence of a definite regional legal tradition and legitimate supranational institutions represents a serious challenge to pluralist and functional theories of integration.

In light of the challenges of an increasingly complex process and further progress of European integration, a few new schools of scholarship emerge from the ranks. The first emerge from among functional theorists, positing a ‘neo-functional’ explanation for regional integration. The goals of neo-functionalism do not preclude the emergence of a supranational state. Analysis of political integration is primarily based on the constituent shift of national interests to a new supranational setting (Haas, 1958, Keeler 1996). The new supranational institution, by seeking to address the demands of new constituents, derives increasing legitimacy for its actions over that of the pre-existing nation-states. The driving force behind the shift of interests from the national to supranational level results from a process termed "spill-over" (Haas, 1958, 283). Like functionalism, neofunctionalism is focused primarily on satisfaction of ‘functions’, such that administrative, technological and economic pathways lead to regional integration much as in the case of the ECJ. Particularly, as integration in one sector occurs, integration in other sectors will be desired and pursued as national leaders and citizens realize that further integration is achievable in additional sectors or is needed to maintain the success of the originating sector (Pentland, 1973, 118, also Tsebelis 1990). Additionally, spill-over can be ideological. If integration is successful in one sector, citizens or political actors may see it as possibly successful in other sectors and may pursue further integration (Haas, 1958: 287 and Gibson and Caldeira, 1995).

Neofunctionalists also posit that the process of integration is not a fast-paced process but a process of slow, gradual change, which they have termed incrementalism. Incrementalism is necessary because political actors, and indeed humans in general, cannot be expected to change their beliefs and motivations overnight. Therefore, regional integration must incremental. It must be a process of gradual change of instrumentally motivated actors to relatively minor changes in mutual policies (Haas, 1975, 12). Neofunctionalists point out that adjustment to spillover takes time and that no government would give up its sovereignty in such a hasty manner.

Similar to neofunctionalism, intergovernmentalist theory evolved with the changing international environment of the 1970s and 1980s. According to Stanley Hoffman and Robert Keohane, this theory derives its beginnings from the European experience in the 1970s. They note that it was during this time that European policy and decision-makers realized their dependence upon world trade and events (Hoffman and Keohane, 1991, 5). The US rejection of the Bretton Woods System and the OPEC oil crisis triggered severe economic crises in Europe, and trade and monetary frictions between Europe and the rest of the world increased. Therefore, intergovernmentalists posit that integration became a process in which European states came to believe they shared definite common objectives (23). Integration came to express the need to for European states to remain competitive and prosperous within increasingly competitive global, regional and local markets.

Intergovernmentalism explains international cooperation as an effort to arrange mutually beneficial policy coordination among countries whose domestic policies have an impact on one another. Cooperation is a means for governments to produce predictability when confronting the economic activities of foreign countries and works for their mutual benefit. These economic activities and international markets transmit policy externalities. The pattern of externalities reflects not just the particular policies countries choose but also their relative positions in domestic and international markets. Where states are able to act in their self- interest without substantial cost, they will act unilaterally. When potential cooperation can eliminate negative policy externalities or create positive outcomes more efficiently than individual responses, governments have an incentive to coordinate their activities. Simultaneously, domestic producer groups, demands for regulatory protection, economic efficiency and fiscal responsibility, and partisan competition influence government policy. International and regional cooperation is thus more likely as domestic and international complexities interact to place a heavy burden upon the state (Moravcsik, 1998, 35-38). While this view posits that the state is ultimate promulgator of national efforts to integrate, interacting domestic and international influences may drive the state to seek assistance by coordinating policy at the regional level.

Synthesis

An examination of these two literatures produces my primary research question: does regional integration preserve or enhance the strength of the modern state? This is not a very contentious issue, as most scholars feel that regional integration weakens the state. However, Alan Milward has argued that integration served to strengthen the European state and assisted it in overcoming the devastation of World War Two (1989). Furthermore, now that Europe’s major powers are very influential actors in the current international system, integration may be a source of strength as they combine economic and political resources. While giving away some sovereignty to regional partnership, integration may serve to protect the state against the complications brought about by globalization and continuing the influence of the global economy. In relation to state strength, this is my first and primary research hypothesis:

Research Hypothesis (1): Globalization weakens the state, while regional integration preserves and enhances state strength.

Regional integration may weaken the state in certain traditional areas but has provided Europe stability and influence in the international system. The Common Market affords these states a mechanism by which they can protect themselves from the uncertainty of international trade and finance thus provides stability. One of the primary goals of regional integration is the development of a common legal framework for trade that serves to deflect many of the pressures of globalization. As a result, other international actors find themselves hard pressed to resort to threats of abandoning relations with one European actor in favor of another over issues of trade. Furthermore, the adoption of the Common Foreign and Security Policy is aimed precisely with this in mind and does not aim for the amalgamation of these states into a supra-state. While I refrain from indicating or determining whether or not regional integration will produce a united European actor, the ability of European Union member-states to coordinate their resources on issues of foreign affairs and war will represent an additional challenge to the United States as pursues its own international military strategy. If this hypothesis is correct, I expect to find that the European states have increased or preserved their strength proportionately more so than other states that have not pursued regional integration in a similar fashion.

Alternate H1: Globalization and regional integration weaken the state.

Alternate H2: Globalization and regional integration do not weaken the state.

Globalization, interdependence and decline scholars would posit that regional integration could not stem the tide of global integration. Therefore, if correct, regional integration will be expected not to possess a significant effect on state strength, but it is expected that globalization will weaken state strength and that this relationship will covary across all states in the international system. Conversely, scholars in opposition to the claims of the globalization and decline scholars pose that modern state is not in decline. States remain predominant actors in the global system. If regional integration does strengthen the state, it is only because certain states, such as the United States in relation to European and Japanese reconstruction, have allowed it. Globalization and regional integration efforts do not weaken the state as they only effect the state in so much as the state allows itself to be influenced by them. These scholars would expect their to be no significant covariance among states in terms of state strength, globalization and regional integration as states are able to pursue effective policy to combat their influences.

The Model

The model I intend to pursue is as follows:

State Strength = Globalization + Regional Integration + Domestic Constraints + _ (error)

I will be comparing data from the United States, Japan, Australia, Canada, Germany, Italy, France and the United Kingdom that will first be analyzed collectively in a pooled time series design. Particularly, the goal of this pooled time series design will be to assess the extent to which state strength differs across these eight major powers over thirty-five years. As I set out in the following section on my research design, this goal will also entail comparison of these states to determine if they significantly covary together as a whole, according to their respective regions or not all, in order to assess the effects of globalization and regional integration. Second, I will also assess the effects of each independent and control variable on each country and compare to see if and which variables influence state strength uniquely or collectively.

Research Design

Operationalization — Dependent Variable

In order to operationalize military strength, I use the value of annual government expenditures devoted to the military for two reasons. First, annual military expenditures denote a state’s current commitment to existing military priorities in regards to other domestic concerns. A relatively high stable rate of military spending relative to other states, for example, indicates that the government and its constituency feel that physical security is an important priority. Second, the increase or decrease of military spending across states indicates a weakening or intensifying trend of potential military conflict. While we know from the Democratic Peace literature that democracies typically do not war with one another, assessing the trends in military spending allows the opportunity to observe whether or not the demise of the Cold War has brought about a shift in priorities from military strength to economic and diplomatic strength. Therefore, I will operationalize military strength in terms of government expenditure on defense as a percentage of gross domestic product.

Military Strength = annual Defense Expenditure (DE) as % of Gross Domestic Product

A second operationalization of state strength measures the total productive capacity of a state. Many authors use Gross National Product (GNP), Gross Domestic Product or either of the two in per capita terms as reliable operationalizations of state strength. (Kugler and Domke 1986, Kugler and Arbetman 1989) In terms of addressing the strength of the state to control resources and outputs, Gross Domestic Product per Capita represents the valued output of society per member of that society. As I seek to measure the state in relation to the resources it governs and may draw from as measures of strength, GDP per capita is an appropriate measure that permits better cross-national comparison as it controls for population. Undeniably, if I were to use GNP or GDP to measure state strength, the United States, with a GNP roughly four times larger than the second most powerful states, Japan and Germany, my estimates of state strength would be biased. GDP per capita still measures the performance and value of the total economy and national resource based with both government and private sectors accounted but averaged against the members of the state. Furthermore, GDP per capita represents a parsimonious and efficient indicator, which is easy to obtain yet contains a maximum amount of information on the performance of the state in a multitude of sectors but does not react to shifts from civilian to military production. GDP per capita will be used as a measure of state economic and resource strength and represents the most important and heavily weighted portion of my state strength index. I will use the value of annual Gross Domestic Product per Capita in 1960 European Currency Units.

Economic Strength = Annual Gross Domestic Product per Capita in 1960 ECUs

My third and final operationalization of state strength has not been given as much attention in the literature devoted to power and state strength. If the number of salient international actors is increasing at a rapid pace as globalization predicts, then the diplomatic strength of state will increasingly become an important factor. Diplomatic power represents the ability to manage conflict, problem solve, negotiate, bargain, and manage programs, cross-cultural interactions, communication and information. (Reychler 1979 and Moravcsik 1993) If interdependence theorists are correct, then increasing globalization will demand that a state be more diplomatically active and alert, as it must respond to the actions of an increasing number of important international actors. In a globalized international economic system, the state will increasingly pursue action through negotiation and bargaining, especially in its interactions with other democratic states. Thus, given a potentially diverse global society, the state must be able to effectively manage and transmit its self-interest to international as well as domestic actors and perceive and receive pertinent information to the formation of that self interest. (Putnam 1988 and Cox 1997) The ability of a state to field diplomatic corps that can represent the national interest, translate policy to other actors and report on international conditions is an important element of state strength.

In order to maintain and promote one’s position and strength in the international arena, a state must be willing to commit fiscal resources to influencing other actors to its position. States do this in several ways. Guaranteed loans, arms sales and direct aid are a few of the primary means states use to exert some influence over others. Often, in the case of Israel, Egypt and the United States, the resources given by one state to others due significantly influence the recipient state’s foreign policy and relations with other states. As reported by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Total Development Assistance (TDA) figures measure the technological, development and other financial assistance given primarily from industrialized countries to developing countries. This assistance is important because it represents a relationship, a formal bond between countries. Rarely is anything given for free, and state’s distributing the assistance usually benefit from increased economic relations or rights to resources from the accepting state. Furthermore, TDA accounts for the loans and assistance a state can draw from its private sector to support its diplomatic position.

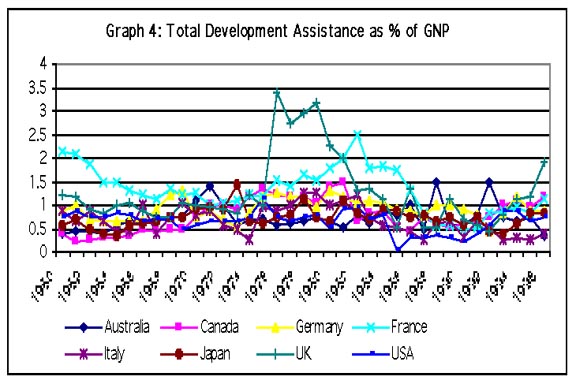

Diplomatic Strength = Total Development Assistance (TDA) as % GNP

Operationalization — Independent and Control Varibles

My first independent variable, globalization, will be operationalized primarily upon state trade figures. However, my argument for using trade as a measure of globalization would be incomplete without a discussion of this concept. As a concept, globalization does not represent a single phenomenon but an overlaying process affecting the conduct of international politics. It is indeed much more than a country’s desire to expand and open trade. References to the processes effected by globalization vary widely in the literature, as scholars refer to the increasing internationalization of production and financial capital (Schwartz 1994), identification as a ‘global’ citizen (Sassen 1996), the proliferation of new actors (i.e., international organizations) that complicate relations and transactions between states (Keohane and Nye 1997a, 1997b and 1998, and Keohane 1998) and to the influence of multinational and transnational corporations on state policy and international markets (Strange 1991, 1994, 1995 and 1998, and Ruigrok and Van Tulder 1995), just to name a few. Furthermore, due to the complex nature of globalization, there are no true quantitative indicators or measures that fully grasp ‘globalization’ in all facets implied by its conceptual definition (Strange 1995, 1998). By taking this into consideration, how can any political scientist or international studies scholar hope to measure globalization?

I admit that I could not possibly hope to measure such a phenomenon in its entirety. However, this being said, globalization is still an important process that requires consideration when examining the relationships between states. Although I noted that globalization represents much more than trade, the international structure of trading relationships is of some interest. Presumably, neoclassical trade theory assumes that states will maximize their aggregate economic utility by maximizing global welfare, which entails achieving as open an international economic system as possible (Krasner 1976). However, trading relations have hardly even been completely open. States employ tariffs to generate income and prevent international competitors from undermining the strength of domestic business. Despite international trade agreements, state will circumvent these by employing non-tariff barriers such as medical and food quality standards that other countries cannot hope to meet. Such non-tariff barriers are also difficult to measure and collection of such data in their entirety would be a challenging endeavor.

However, a definite relationship between the openness of the state to international trade and globalization emerges. Despite barriers to trade, as globalization increases, states should become increasingly open to engaging in trading relationships. Advancements in technology should play a fundamental role in decreasing the costs to trade and market entry as transportation, advertising and marketing costs decline. Furthermore, the most powerful states in the international system should be likewise effected but should engage increasingly in trade with all countries, industrialized and developing, to achieve the greatest possible utility from their trading relationships. The ability of one state to dominate the structure of international trade is also affected, as it becomes increasingly cheaper for smaller states to trade. Therefore, there are a few important indicators that can capture the tug and pull between the globalization of trade and its effects on the state.

Openness to Trade = [State Trade]/[Gross National Product]

State Trade= [Imports + Exports] / 2

Of course, these operationalizations will draw criticism for their focus solely on trade. But what else to use? Based on the arguments of Susan Strange against quantitative indicators, her best suggestion would lead on to focus on the role of multinational and transnational corporations in international system (1997 and 1998). Primarily, their offshore operations, seeming borderlessness and vast financial resources make the terribly difficult to govern not too mention an added burden to a state’s diplomatic efforts. States must now bargain and negotiate with these powerful corporations in addition to their relationships with an increasing number of states and international organizations. Dr. Strange recommended detailed analysis of multinational and transnational activities and relationships to states in order to unearth the true effects of globalization. Only then, she claimed, would we be able to realize the extent of the influence that these corporations and globalization represent to the current international system.

However, based on the evidence of a few scholars who have pursued this recommendation, I can not agree with her. Not yet anyway. In particular, Winfried Ruigrok and Rob Van Tulder conducted a survey of the top one hundred multinational corporations. They could not find a single instance of any of these corporations truly fitting the description of a transnational corporation. All had permanent headquarters in the states from which they originated and where they are fully responsible to the home government. They did discover that about forty of these corporations generated at least half of their sales abroad and twenty that maintained at least half of their production facilities abroad (1995, 159). Despite this, nearly all of these multinational corporations executive boards, research and design efforts and corporate finances were decidedly domestic based. The perils of unstable international finance and coping with new legal systems largely serves to block the ascendance from multinational to transnational. Given these findings, I remain unconvinced of the emergence of the transnational or multinational corporation as an international actor worthy of measurement.

My second independent variable, regional integration, is an interesting concept. Why? Primarily, I think it is because regional integration occurs at so many different levels worthy of analysis. Indeed, one can think of hundreds, if not thousands, of ways integration could and does cause states to relinquish sovereignty. However, given that I am controlling for globalization by focusing on the international structure of trade, I will rely on trade as a measure of regional integration. To do so also requires the definition of ‘regions’ as defined in the International Monetary Fund’s Direction of Trade Statistics Yearbook and Quarterly statements. (Appendix One) I use the percentage of overall trade with a state’s region as my primary measure:

Regional Integration = [[Exports to Region + Imports from Region] * 0.5] /GNP

In regards to the relationship between state structure and state strength, the most important dimensions of state structure that requires countenance concerns the role of the government in economy and centralization of government powers. Particularly, John Ikenberry noted how important these matters were in determining state responses and policies toward the oil shocks of the 1970s (1986a and 1986b). In this regard, annual total government expenditures represent the involvement and role of the government in the market, whether it be taking a guiding role or in letting market forces work for themselves. On the other hand, annual central government revenues represent the concept of centralization of power. Particularly, the revenues allotted to the central government denote the ideological choice of a polity as to role of power in society. Strong centralization of power will be evident in the increased centralization of the funds allotted to the federal government. Thus, these two operationalizations represent the centralization of power in certain actors hands as well as the overarching role of government in the economy.

State Structure = Total Government Expenditures (TGE) as % of GDP

State Structure = Central Government Expenditures (CGR) as a % of TGE

In examining the relative strength between democratic major power states, there are domestic constraints that affect the ability of statesmen and policy makers to pursue international policy which must be controlled. Particularly, democracies are domestically constrained in two important ways. First, as Lindblom noted, democracies are fundamentally designed as institutions that grant political and economic liberties to the citizenry that it governs (1977). Politically, therefore, it is more challenging for democratic systems to arrive at a fundamental consensus on policy. Representative government, in any form, requires legislators and executives to be responsive to their constituencies. These constituencies can be expected to hold domestic concerns that will conflict with the pursuit of external policy as they compete for budget resources. Furthermore, the more partisan a particular legislature, the more difficult it will be to adopt legislature, pursue policy and extract resources from society. (Domke 1989) In addition, even less is accomplished in an election year, as attention and resources are occupied with maintaining or attaining public office. Subsequently, to measure domestic political constraint, the partisan division of each government will be employed with a dummy variable representing whether or not an election occurred in a particular year.

Domestic Political Constraint = % Majority of Seats of Governing Party or Coalition

Domestic Political Constraint = Dummy Variable for an Election Year

Domestic Political Constraint = Dummy Variable for Presidential System

There are also domestic economic restraints that affect state strength. The debt accumulated by the national government can severely constrain its ability to pursue present and future policy and also can represent the degree to which it may be influenced by international actors. First, the greater the debt a nation holds, the higher the annual interest payments it will have to make to its creditors. When interest payments consume a large portion of government expenditures, intuitively, that government will be able to devote increasingly less resources to any policy area. Second, the debt itself may present a constraint on policy makers. National debt is unlikely to be by held exclusively by domestic financiers. As financial resources trend toward transnationality, governments are increasingly at the hands of financiers from other states and transnational sources. As national debt grows, these financiers will be more likely to desire to turn their interests into some form of equity and can use their leverage to influence policy makers on international issues for their benefit. (Strange 1998) As debt increases, interest payments will rise, leaving the government fewer resources to use to manage the public and private sectors. In addition, consumer price inflation directly affects the spending and consumption ability for constituents, thus placing a burden upon policy makers should it rise or decline abnormally. To account for domestic economic constraints, the percent of the budget devoted to interest payments and the annual CPI will be controlled.

Domestic Economic Constraints = Annual Interest Payments as % GDP

Domestic Economic Constraints = Annual Inflation Rate

The Period of Study

The observed time period of this study is dependent upon the amount of detailed trade data I can gather for the countries involved. I would like to obtain data beginning with 1950, but data becomes increasingly hard to reliably obtain prior to 1965. I will also break my longitudinal analyses down to periods of time from certain events using a dummy variable, such as the date of the end of Bretton Woods, The Single Europe Act, Maastricht, etc., to ascertain their impact on state strength.

Sample Size

Choosing which countries to observe for analysis is theoretically very important. First, as I am also concerned with the structure of power in the international system, I am only concerned with those states that are major powers within it. Additionally, I am limiting myself to the study of established democratic systems, for which data collection is much more feasible than with autocratic powers who can be reserved about the spread of information. Who are the major powers in the current global system? For the purposes of this paper, I define these primarily by their international involvement and democratic system but also by their importance in their respective particular region. The United States, Japan, Italy, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, France and Germany will be the countries under study. Why these countries? During the majority of the Cold War, these states were also the most powerful Western countries as well. Today, while the debate ranges on a unipolar versus multipolar international system, these states continue to be important major economic and political powers. While Italy may not be as powerful or influential, it continues to be a major power in Europe and is thus included. Likewise, Canada and Australia are not known typically known as major powers but play important roles regionally and internationally, particularly in their involvement with the United Nations and peacekeeping.

Given my predominant concern with the major powers of Europe, the inclusion of Japan and the United States is an important control issue. First, the importance of the United States is important to assess the power distribution of the current international system as well as to measure the economic and military gains or losses Europeans have made in comparison to the United States, which was the preponderant Western power during the Cold War. Second, Japan is also important. Not only did the United States invest in its future much in the same way it initially assisted in the rebuilding of Europe following the devastation of World War Two. Like Europe, Japan made a strong recovery and has become an important actor in many international arenas and especially in Asia. Including these two countries helps this project to gather a sense of the shape of the power distribution among the most powerful capitalist democracies and also as parts of the global system.

Findings

Before discussing the substantive findings of the panel model, the statistical model itself presented a few problems. Particularly, in using a panel model, I encountered two problems: Heteroskedasticity and Autocorrelation. First, heteroskedasticity, if present, will produce estimators that are no longer of minimum variance or efficient. This means that confidence intervals will be increased, t and F tests will be inaccurate and inferences will be biased and inefficient. Second, autocorrelation represents a special problem for panel designs. Not only may the individual cross sections and time series possess autocorrelation, but spatial autocorrelation represents may occur, whereby the errors adjoining one another in ‘space’ are correlated. The presence of any of these three types of autocorrelation will serve to bias estimates of the standard error of slopes and thus to produce inefficient estimates.

In tackling these two problems, I employed three methods that make proper adjustments and produce BLUE estimators. First, I included a single lag of the dependent variable in each model, which assists in correcting for autocorrelation. The inclusion of a lagged dependent variable does not only serve statistical purposes but fits well with the theoretical intent of each model. It is common knowledge that past behavior influences present actions. Governments base current budget projections on past needs, and trade relationships continue based upon the satisfaction of previous contracts. Second, in accord with including a lagged dependent variable, I included a single lag of the independent variables of interest using the same logic. While I include lagged variables for statistical and theoretical purposes, their slope values are unimportant as I am only attempting to use them to correct for autocorrelation and adjust for any time dependencies. Third, I employ panel corrected standard errors, as suggested by Beck and Katz (1995). They note that Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) estimation assumes that standard errors at one particular point in time are unrelated to the errors for every other unit, i.e., that there is no spatial autocorrelation. However, given joint influence of the past behavior of the dependent variable upon itself and the past and present influence of the independent variables of substantive interest, this is a very unrealistic assumption. Therefore, I use panel corrected standard errors, which account for the presence of spatial autocorrelations. The Durbin-Watson h value for each model indicates I have corrected for these problems, as its value is less than 1.65 (t>.10) in all models.

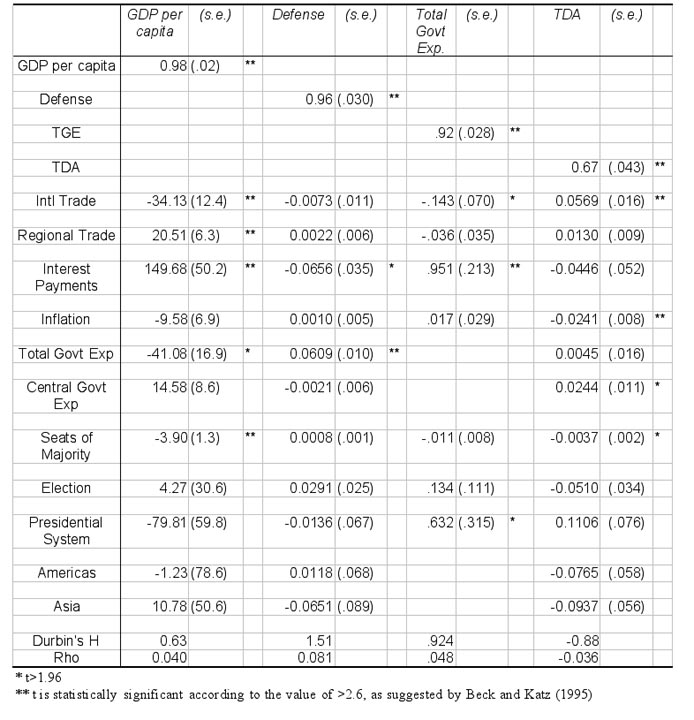

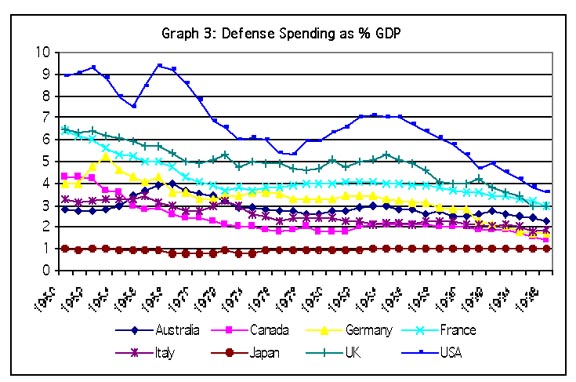

The substantive findings largely confirm my expectations. For my measure of economic strength, gross domestic product per capita (Graph 1), the living standards for the citizenry have increased and with this increase, economies have prospered. The increased internationalization of trade bears a negative effect for economic strength, but states have countered this effect by pursuing cooperation and integration at a regional level, which increases economic growth per capita. The member-states of the European Union would seem to be at an advantage in this regard. Their attempts to coordinate regional cooperation far surpass all other states in the current international system. Regional integration offers the opportunity to pool resources to deflect some of the negative externalities of the internationalization of trade, capital and investment and provides allies in dealing with them.

Despite this, states are not unique in the effects of domestic constraints and government structure upon economic growth. My results also indicate that government involvement bears a negative effect on economic growth. While initially puzzled that interest payments held such an intense positive effect towards economic growth, this particular result only reinforces the negative effect of an increased role for government in society. As interest payments increase, governments have fewer resources at their disposal with which to control the economy and society. Given that governments only possess a limited revenue base for each year, they do possess the option of borrowing to meet expenditure needs, such as the United States has done in the 1980s and early 1990s under the Reagan and Bush Administrations. Unfortunately, this is only a short run solution. As debt accumulates, interest payments increase, and governments will possess even fewer resources and opportunities to directly manage the economy and society.

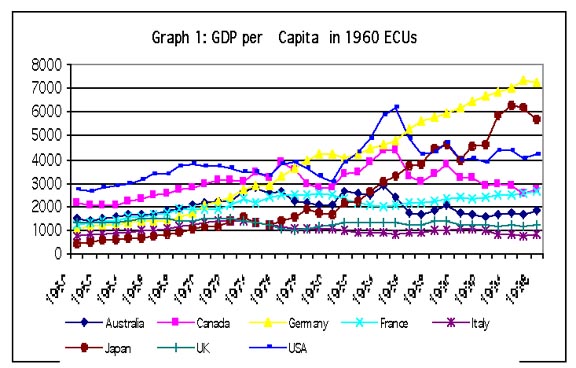

The Japanese, while currently mired in economic recession, represent a good example of this model, as the Japanese economy grew faster than any other state over this time period while its government spent the least relative to its economy. However, to state that a lack of government involvement is a necessary condition for economic growth would be naïve. Indeed, if one examines total government expenditures (graph 2), one will find that they have increased on average fifteen percent since 1960. It appears that less involvement is better tight state control over the economy, but the increasingly complexity of international trade and other globalized processes requires the state to take a more active role. While the Japanese have advanced economically with less relative government involvement, the state plays an increasingly important role in dealing with the international economy.

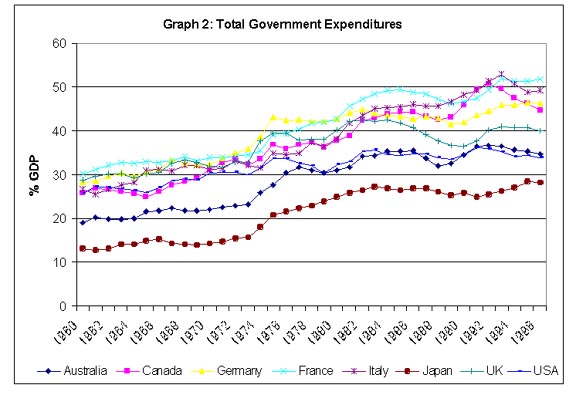

While I have not judged the change in the levels of conflict over this period, the expenditures on defense among major actors dropped significantly through this period, most notably after the end of the Cold War. Governments are spending relatively less per capita than at other times during this period, and defense expenditures continue to decline. In order to explain the decline of defense spending and the impact of government spending, the independent variables of interest were examined against total government expenditures. As one can see, the decline in defense spending is due largely to the effects of the international economy and also an increase in interest payments. These states are no longer engaging in direct conflict with each other nor with other major actors in the world system. Thus, the major battlefields are becoming markets and international organizations. As long as this trend continues, it seems unlikely that defense spending will return to previous levels.

Finally, the measure of diplomatic relationships, total development assistance, has remained relatively constant (Graph 4). These states devote regularly devote less than one percent of their gross domestic product to development assistance, and this has not changed since 1960. While absolute assistance has increased, states are providing more assistance relative to the resources available to them. It is little wonder that North-South relations sour from time to time. The major actors in world system have not been willing to take a more active role in employing their resources to assist developing countries.

Despite the positive influence of the internationalization of trade and regional integration, domestic factors clearly pay an important role in determining assistance. Significantly, all four domestic factors measured had a negative impact upon development assistance spending. This is important because it represents a crucial tension between levels of analysis in assessing the strength foreign policy makers have at their disposal. The process of globalizing trade, finance and capital is not likely to be met passively by domestic constituencies who are threatened by competition from foreign sources or who feel helpless when decisions by other states hold negative impacts. As the recent hikes in oil and gas prices demonstrate, constituents are most likely to react negatively when international decisions hit their pocketbooks.

Conclusion