CIAO DATE: 7/00

Exploding the Value Chain: The Changing Nature of the Global Production Structure and Implications for International Political Economy

Thomas C. Lawton and Kevin P. Michaels

International Studies Association

41st Annual Convention

Los Angeles, CA

March 14-18, 2000

Abstract

Contrary to recent critical thought, something has changed between the globalisation process of the late 19th and late 20th Centuries. There has been a fundamental change in what Strange (1988) defined as ‘the production structure’. We begin this paper by examining Strange’s notion of the production structure and its place in structural power. We then proceed to discuss the changing process of globalisation and the growth in intermediate products, deconstructing Michael Porter’s value chain concept in the process. We argue that, in addition to developments in communications, the ‘new globalism’ is characterised in large part by changes in the production structure. These changes are facilitated by the advent of e-commerce. For governments to adapt to this new environment, they need to think in terms of how to gain or maintain comparative advantage in a particular part of the value chain.

Introduction

In the late 1980s, Strange first conceptualised power in the international system in terms of four interrelated structures - security, knowledge, finance, and production. She defined the production structure, the primary creator of wealth in the international system, as ‘the sum of all arrangements determining what is produced, by whom, by what method and on what terms (1988, p. 62).’ The location of productive capacity, she contended, is far less important than the location of the people who make the key decisions on what is produced, where and how, and who designs, directs and manages to sell successfully on the world market. Viewing international wealth creation - and associated power - through this prism, led Strange to some controversial conclusions about the international system. One of her conclusions was that U.S. control over international production had increased despite a diminishing share of world trade; U.S. hegemony was as strong as ever, only the will to exercise power had declined. She described the American Empire as a ‘corporation empire’ in which the culture and interests of corporations are sustained by an imperial bureaucracy of not only of U.S. government agencies but international organisations and regimes such as the OECD, IMF, and GATT (1988, p. 5).

Strange also highlighted the growing importance of international production sharing. In the mid-1980s, the volume of international production sharing exceeded the volume of international trade for the first time. The change is significant as it diminishes the power of states to control economic events. States retain considerable negative power to disrupt, manage, and distort trade by controlling entry to the territory in which the national market functions. However, they cannot so easily control production that is aimed at a world market which does not necessarily, take place within their frontiers (Stopford and Strange 1991, p. 14). This contention led to perhaps Strange’s most controversial assertion: transnational corporations, controlling the vast majority of international production, had assumed a role alongside states as primary actors in the international system. Economic security had lost its national character - international firms and markets could now be considered as influential as national governments (1986, p. 296). As a result, states - with less capability of pursuing independent economic policies - had to master a new task: bargaining with, rather than directing transnational corporations.

There have been significant changes in the nature of international production since Strange made these original arguments in the late 1980s. Among the changes are a surge in manufacturing and service exports, a shift in the composition of exports to high technology goods, and the continued growth of international production sharing. These changes are driven in part by changes in the transnational corporation itself, where vertical integration is becoming less desirable, while ‘horizontal specialisation’ on an international basis is becoming more common in scores of industries. Moreover, changes in technology are allowing transnational corporations (TNCs) to tightly integrate functions such as operations, logistics, and research and development on a global basis both within the firm and between firms - a trend that appears to be accelerating in the late 1990s with the onset of electronic commerce via the internet. Indeed, the impact of the internet on international production is and will be revolutionary for the foreseeable future.

These changes raise interesting questions for Strange’s aforementioned assertions about the production structure. Is the concept of the production structure still valid? Have changes in international production increased or decreased U.S. influence over the production structure? What issues do these changes raise for policy makers and international political economy (IPE) - as well as international business - theorists? This paper therefore has twin objectives: 1) To describe some of the key changes in international production in the 1990s and, 2) in light of these changes, analyse the continuing relevance of the production structure for IPE theory and policy makers alike.

Changes In International Production

The past decade has witnessed many changes related to international production, caused by both political and technological factors. On the political side, the successful completion of the GATT Uruguay Round, the emergence of the World Trade Organisation, and a general trend toward deregulation and privatisation by governments around the world has created a favourable environment for global production and international trade. Technology has also shaped international production as a result of falling transport and communications costs, the onset of the internet and e-commerce, and the emergence of a new breed of service sector TNCs: global logistics suppliers. While the changes in international production are numerous, this paper will highlight three trends with particular relevance for IPE: surging global trade, particularly in high technology goods and services; de-aggregation or ‘explosion’ of the production value chain, and the emergence of tightly integrated international production systems.

Surge in International Trade

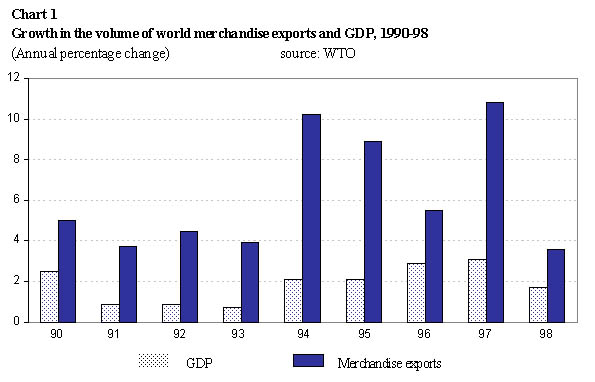

The decade of the 1990s was characterised by significant growth in world trade in both goods and services. Merchandise exports averaged 7 per cent annual growth between 1990 and 1997 to reach $5.3 billion. Over the same period, exports of services grew at an 8 per cent annual rate to reach $1.3 trillion by 1997. Considering that world GDP averaged approximately 2 per cent growth over the same timeframe, the record is impressive indeed.

(WTO 1998, pp. 73-74)

The 1990s record of trade growth, on the heels of another strong decade of trade growth in the 1980s, led some commentators to proclaim a ‘new era’ in the world economy on the basis of globalisation. While there has been a trend of growing trade since 1945, international trade is approximately the same share of the world economy as it was 100 years ago prior to the two world wars (Henderson 1998, pp. 34-67). Thus, while the current levels of international trade are not unprecedented, it is clear at the close of the 1990s that we are in a robust period of international trade growth. Despite this assertion, the authors of this article are not pop internationalists! 1

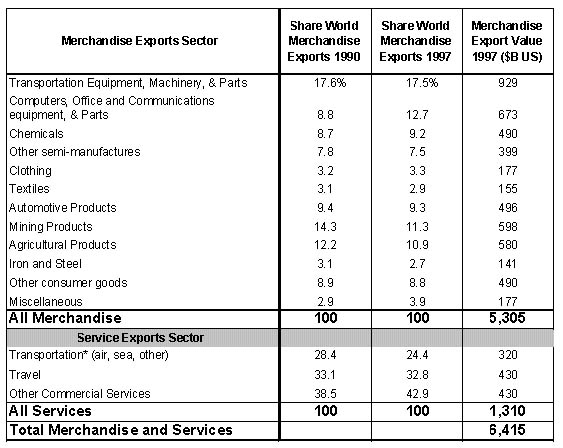

Along with robust trade growth has been a shift in the composition of trade favouring high technology products with reduced contribution from basic materials and agricultural goods. A review of merchandise exports for the 1990-1997 timeframe in chart 2 is illustrative.

Chart 2 1997 Merchandise and Service Exports

The percentage of world exports attributed to agricultural products declined from 12.2 per cent to 10.8 per cent; mining products similarly shrank from a 14.3 per cent share of exports to 11.3 per cent. The 1990s were not a favourable decade for raw material trade! At the same time, the share of office and telecommunications equipment sector as a percent of exports grew from 8.8 per cent to 12.7 per cent to reach $673 billion in 1997 - a substantial increase for a seven year timeframe and nearly identical to the decline in agricultural and mining products. The products making up this sector include computers and communications equipment, the basic building blocks of the internet and the information economy. The contribution of other key sectors such as automotive, chemical and consumer goods to exports roughly held their own over the timeframe, increasing at a the same rate (7 per cent per annum) as overall merchandise export growth, but again significantly faster than world GDP growth. The data for service exports has less granularity (and by the WTO’s admission, less precision) than merchandise figures, but does highlight declining contribution of transportation services as a result of fallings real costs, from 28.4 per cent to 24.4 per cent, to overall international service trade from 1990-97. In summary, while international trade grew at a robust pace in the 1990s, the composition of trade shifted away from raw materials to favour high technology goods.

The Exploding Value Chain

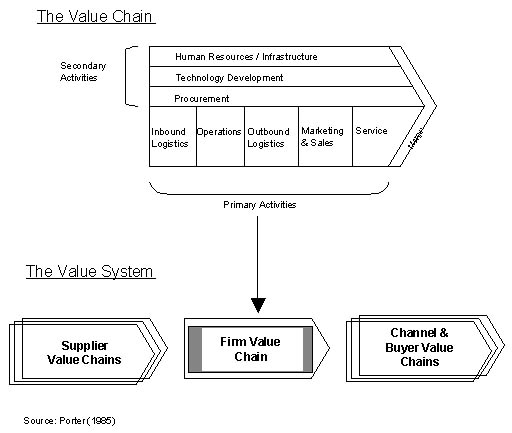

A second important trend in international production is the growing physical separation of activities defining the value chain of the firm. As defined by Porter, the value chain is a collection of activities that are performed by the firm to design, produce, market, deliver, and support a product or service (1985, p. 36). The configuration of a firm’s value chain - the decisions relative to the technology, process, and location and whether to ‘make or buy’ each for each of these activities - is the basis of competitive advantage. The value chain is, in turn, part of a larger value system that incorporates all value-added activities from raw materials to component and final assembly through buyer distribution channels.

Chart 3 Porter’s Value Chain and Value System

For much of the Twentieth Century, the value systems of many sectors were influenced by mass-production techniques pioneered by Henry Ford in the 1920s, which emphasized scale, standardization, and vertical integration to increase automobile production productivity. The epitome of ‘Fordist’ production was the River Rouge (Michigan) production facility, which was co-located with a port and steel foundry. Most value-added activities were confined to a single facility to improve coordination and reduce the transportation costs of intermediate goods.

A direct challenge to this production model emerged in the 1950s and 1960s from the Toyota Motor Company in Japan (Womack, Jones, Roos 1990). In place of standard products with long production runs by self-reliant vertically integrated firm, Toyota emphasized rapid product innovation, flexible production, and just-in-time inventory systems. Rather than vertical integration, Toyota emphasized strong relations with suppliers clustered near final assembly facilities. The productivity advantages of the Toyota lean production approach were significant, as Toyota could produce an automobile with less than half the labour hours of its American and European competitors. The Toyota model continued to evolve with falling transportation and communications costs in the 1970s and 1980s and soon it became feasible to coordinate large, extended supply chains on a global basis. 2 This production model, which some scholars have dubbed ‘post-Fordist’, spread to other manufacturing sectors beyond automotive and facilitated ever-greater movement of intermediate goods and components across national borders. 3

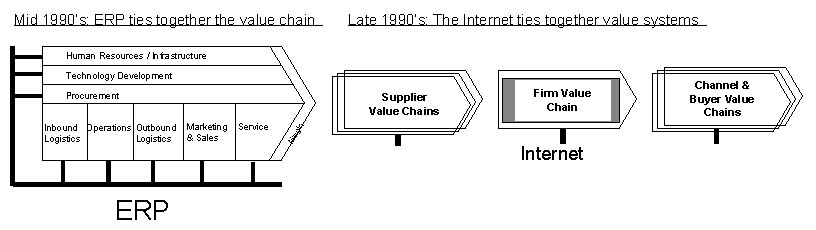

The growing use of information technology in the 1990s brought further innovation to the post-Fordist model. The introduction of ‘enterprise resource planning’ (ERP) software improved intra-firm coordination between frequently disparate functions as conceptualized in Porter’s Value Chain. Prior to ERP, key functions of the value chain — such as inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, and marketing — frequently had separate organizations, with separate information systems that did not easily share information with each other. Each function was, in effect, in a ‘silo’ performing its own task but not optimizing overall operations. ERP created an ‘electronic nervous system’ to link each function together, improve decisions, and increase overall productivity. Consider the impact on the operations and inbound logistics functions of a typical manufacturing firm. Historically, the operations (manufacturing) function demanded high inventory levels to ensure smooth production and avoid costly production shutdowns. At the same time, the inbound logistics function was focused on minimizing transportation costs. The result was excessive inventory levels that were replenished periodically in large batches by slow, inexpensive transportation alternatives. Enterprise resource planning broke down information barriers between ‘functional silos’ to shed light on the relationship between transportation costs, inventory levels, and operations. In some cases, firms found that they could eliminate most inventories by shifting to faster, but more expensive transportation alternatives (like air cargo) that replenished supply just-in-time. Simply put, ERP allowed information to replace inventory.

Chart 4: Impact of ERP and the internet on value systems

Revolutionary advances in communications technology spurred further evolution of the production model in the late 1990s. The emergence of the internet as a low cost conduit for sharing vast quantities of data facilitated more and more information sharing between firms, extending the benefits of ERP from the value chain of an individual firm to the entire value system of firms and their suppliers and customers. One of the early pioneers of this model was Dell Computer, which produced custom-made computers ‘just in time’ for orders received directly from the customer via telephone or the Internet. As Dell received an order, it shared production requirement information electronically with its suppliers worldwide for immediate delivery to a Dell production facility, where the computer was assembled and shipped directly to the customer within a week. The Dell model relied on "demand side pull" rather than "supply side push" - no computer was produced unless there was corresponding demand in the marketplace. Thus the massive queues of inventory usually sitting idle within retail stores, distributors, and factories were virtually eliminated. The productivity advantages of this production model were profound. Dell was able operate with half the number of employees and one-tenth of inventory of its traditional computer competitors. Return on invested capital reached 195 per cent in 1999 compared to 10-20 per cent for traditional manufacturing firms. 4 Soon, companies from around the world were flocking to Austin, Texas to understand the Dell production model, much as firms had flocked to Tokyo and River Rouge earlier in the century. The opportunity for productivity improvement was enormous; in the U.S. alone, the cost of goods in inventory of all value systems was nearly $1 trillion in 1997. 5 As the decade closed, the ‘Dell Model’ began to spread from high technology to traditional manufacturing sectors like automobile production. In late 1999, General Motors and Ford announced they were moving to electronic supply chain management systems similar to Dell Computer. If successful, the "Dell Model" could beevery bit as revolutionary to the production structure as Ford’s vertical integration and Toyota’s "lean production" models were in earlier eras.

One major consequence of the ‘exploding value chain’ is the growth of trade in parts and components as distinct from finished products. A study by the World Bank (Yeats 1998) estimates that the share of parts and components accounts for some 30 per cent of world trade in manufactured products. Moreover, trade in components and parts is growing significantly faster than in finished products, highlighting the shift to international production systems. New types of value systems are emerging. In the transportation and machinery sector, for example, OECD countries were net exporters of parts and components (surplus of $77 billion in 1995), signifying the comparative advantage that many developed economies have in capital-intensive components, as well as the comparative advantage that many developing countries have in labor-intensive assembly operations. Over 40 per cent of the exports of manufactured goods from Mexico, for example, involve assembly operations using components manufactured abroad.

More Trade Controlled By TNC Networks

A third major international production trend is the growing influence of TNCs in international trade. With the number of TNCs increasing from 7,000 in 1975 to 40,000 in 1995, and foreign affiliates of TNCs accounting for 25 per cent of world manufacturing output, an increasing proportion of world trade in manufactures is intra-firm, rather than inter-national trade. In other words, it is trade that takes place between parts of the same firm but across national boundaries. Gilpin (1987) was one of the earliest writers in IPE to recognise the significance of this shift in trade patterns. He argued that:

the result of this internationalisation of the production process has been the rapid expansion of intra-firm trade. A substantial fraction of global trade has become the import and export of components and intermediate goods rather than the trade of final products associated with more conventional trade theory (1987, p. 238).

The current estimate is that about 30 per cent of world trade is intra-firm (Karliner 1997; WTO 1997). The upshot of this activity is that unlike the kind of trade assumed in traditional international trade theory, intra-firm trade does not take place on an ‘arms length’ basis. It is therefore, not subject to external market prices but to the internal decisions of TNCs. Such trade may account for a very large share of a nations exports and imports. Dicken has noted that more than 50 per cent of the total trade (exports and imports) of both the United States and Japan consists of trade conducted within TNCs, and as much as four-fifths of the United Kingdom’s manufactured exports are flows within UK enterprises with foreign affiliates of within foreign controlled enterprises with operations in the United Kingdom (1992, p. 49). The economic power of TNCs is pervasive. Widening the prism beyond simply intra-firm trade, TNCs are involved in 70 per cent of world trade (Karliner 1997).

To summarise the trends in international production outlined in this section:

Implications For Policy Makers

For policy makers, there are a number of important implications of the changing nature of international production. For one, the splintering of the value chain in many industries may hearken the need for a new approach to industrial policy and wealth creation. Industrial policy - which traditionally has focused on particular industries or sectors - may now need to adopt a more functional approach (Lawton 1999). Returning to Porter’s value chain, policy makers may need to focus on creating comparative advantage in particular functions such as operations, logistics, or research and development rather than specific industry sectors such as semiconductors or aerospace. This appears to be the conclusion reached by Taiwan, a state with considerable success in expanding wealth over the last three decades. The current blueprint for economic development calls for Taiwan to become an Asia-Pacific Regional Operations Center (APROC). Focusing on improving the removal of impediments to the free flow of goods, information, capital, and personnel, Taiwan seeks to be the gateway to the Asian market for local firms and TNCs alike (CEPD 1997, pp. 3-4). Among the goals are to dramatically increase the competitiveness of air and sea transportation, communications, and financial services — the very linkages that tie value chains of firms together. Taiwan is betting that firms will locate their operations in countries where these support services are most competitive. This is a significant contrast with high profile sectoral industrial policies of recent years such as Japan’s fifth generation computer, the U.S.’s flat panel display, and Europe’s semiconductor initiatives - endeavours that have all arguably failed. Taiwan’s APROC objective acknowledges that ‘picking winners’ in an era of rapid technological change is an increasingly difficult and risky proposition.

A second implication of the changing production structure for policy makers, implicit in the Taiwan example, is to pay attention to infrastructure — particularly ‘fast’ infrastructure such as communications and air transportation. The changes in production outlined in this paper, including the development of tightly integrated international value systems and the emergence of electronic commerce over the internet, point to greater importance for transportation and communications public policy.

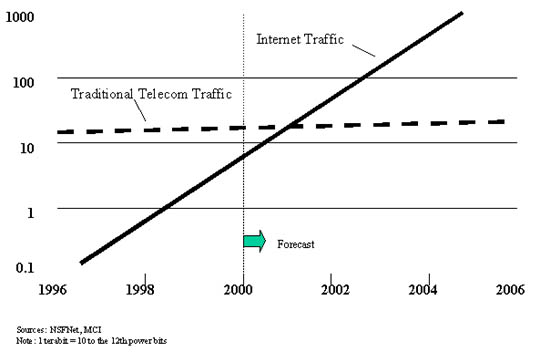

Data volume over the internet is growing at an exponential pace — about 10 per cent per month - and will soon surpass voice traffic carried over the traditional communications infrastructure. Much of this growth is fuelled by the globalization of production and the onset of electronic commerce. Moreover, as Chart Five illustrates, if current trends continue, internet traffic will be one hundred times greater than traditional voice traffic before 2010. Increasingly, firms will rely on abundant and cheap communications services to develop new products and services, integrate their supply chains, and to simply remain competitive. This means that governments focused on economic growth must carefully craft telecommunications policies — including regulation, taxation, and public ownership -- that encourage the development of a state-of-the-art infrastructure to the greatest extent possible. The challenge for developing countries lacking capital for such a build out will be especially acute. Increasingly, cooperation with telecommunications TNCs rather than protection of domestic suppliers will be required to develop this version of ‘fast infrastructure’, which is critical for economic development in an era of exploding value chains.

Chart 5 Growth of Internet vs. Traditional Telecommunications Traffic 1996 — 2006

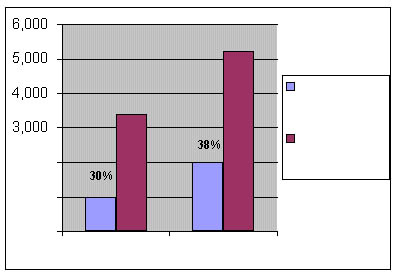

While the explosion of internet traffic has received headlines, another type of ‘fast’ infrastructure is gaining importance: air cargo. The changes in global production outlined in this paper have contributed a 600 per cent increase in air cargo traffic between 1977 and 1997. As a result, in 1998 nearly 40 per cent of the worlds merchandise trade by value moved by air cargo, up from 30 per cent in 1990 (chart six). In some Asian countries, the figure exceeds 60 per cent. 6 Airports are becoming magnets for economic activity, much like the historical role of maritime ports. Policy choices relative to air cargo service will therefore become more important than ever. Historically, the focus of governments - in negotiating air service agreements that regulate air travel between two countries - has been on passenger travel. The result has often been insufficient capacity or competition to adequately serve the needs of cargo customers. Another public policy issue deserving focus is the role of customs in a world of fast infrastructure. Traditionally an unglamorous (and many times corrupt) government agency focused on revenue generation and policing, customs plays a growing role in facilitating the rapid movement of goods. Transparency, speed, and 24 hour service are what TNCs require in an era where inventory levels are measured in hours rather than days or weeks. Policy makers that wish to attract TNC investment must now balance the security requirements of the country with the economic necessity of efficient customs procedures.

Chart 6 Air Cargo Shipments By Value, 1990 — 1998 ($US million)

Due in part to the emergence of fast infrastructure, comparative advantage has never been so mobile. Some regions are adept at wealth creation because their governments have learned how to gain advantage through time efficiencies. A good example of this phenomenon is Scotland, which has created a manufacturing centre for high technology goods, known as the ‘Silicon Glen,’ in the past decade. According to a TNC executive with a computer facility in Scotland:

Before, nobody was really producing in Scotland. Now, you can’t afford not to go there. Why? Because they have constructed an infrastructure. If you go to Scotland everything is ready — the regulatory system, the tax environment, the transportation, the telecommunications — for you to set up your manufacturing facility as fast as you can. (Friedman 1998, p. 174)

This points to a paradox: in an era when the TNC may well be the single most important force creating global shifts of economic activity, political spaces are among the most important ways in which location specific factors are packaged (Dicken 1992, pp.148-49) and ‘fast’ infrastructure will become an increasingly important location specific factor.

A final implication for policy makers to consider is that the creation of public policy will become more complex as a result of changes in the production structure. A mixture of subnational actors, international institutions and TNCs now have a voice in many public policy decisions that were once the exclusive domain of state governments. Strange and Stopford (1991, p. 2) referred to this as "new diplomacy": the concept that governments must bargain both with firms and governments. This point is best illustrated with an example, again from Scotland. In early 1999, FedEx, a U.S.-based air cargo TNC, decided that it wanted the right to fly direct cargo flights from Prestwick, in the heart of Scotland’s computer industry, to Paris, its European air cargo hub. Frustrated that U.S. - U.K. government negotiations for expanded European air traffic rights were stalled, FedEx took an unorthodox step and unilaterally applied to the British Government for these rights. Traditionally, air traffic rights are handled by government-to-government negotiations, not by petitions from TNCs. FedEx indicated to the British Government that if not granted additional U.K. traffic rights to France, it might be forced to ‘severely’ scale back its trans-Atlantic flights to Prestwick, a move that was sure to damage the operations of Scotland’s computer industry. Interest groups on both sides of the issue quickly formed. Opposed to granting FedEx additional rights were a group of British air cargo carriers, who wanted concessions in the U.S. market as a quid pro quo. Supporting FedEx were local government authorities, development agencies, and scores of mainly U.S. microelectronics and computer equipment firms from the Silicon Glen. A fierce public relations battle ensued, with one British executive accusing FedEx of trying to blackmail the British government. In late 1999, the British government announced that it would grant FedEx the air traffic rights it desired. FedEx even managed to upstage British carriers on their home turf when it was revealed that the FedEx Chief Executive Officer met directly with the British Deputy Prime Minister to advocate his position, while British carriers were only able to muster an audience with his junior Transport Minister. 7 While other factors - including domestic politics - may have played a role in the British government’s decision, it appears that in this instance a coalition of subnational actors, a U.S. air cargo TNC, and U.S. computer and microelectronic TNCs were able to exert significant influence on British public policy formulation. Admittedly this example is anecdotal, but it does illustrate the increasingly complex nature of public policy creation in an era of tightly integrated production systems. This may drive governments to create different types of institutions to ensure better coordination with subnational actors, TNCs and international organisations.

What Does This Mean For IPE/IB Theory?

What do these trends in international production mean for Strange’s perspective of the international system in particular and the study of IPE in general? First and foremost, Strange was a clairvoyant in anticipating - and interpreting - major changes in international production that are shaping the international system today. The empirical evidence indicates that the growth of global production sharing continues to gain momentum as a result of what we have termed ‘the explosion of the value chain’. In the early 1990s, Strange and Stopford pointed to three factors that would drive greater production sharing: lower transport and information technology costs; provision of more sophisticated financial instruments; and new technologies that have altered the scale needed for efficient operation (1991, pp. 35-7). A decade later, we live in a world increasingly tied together by the internet, a world where it is possible to outsource manufacturing and logistics to sophisticated global suppliers, a world where microprocessor designs are developed 24 hours per day by electronically transmitting designs between Asia, Europe, and North America. Indeed global production sharing is now much larger than foreign direct investment, the traditional focus of much IPE literature.

There is another critical consequence of the explosion of the value chain for IPE theory: it has facilitated what Bhagwati referred to as the ‘splintering’ of goods and services (1997, pp. 437-8). For example, the inbound and outbound logistics functions, traditionally performed internally by manufacturing firms, are now often outsourced and purchased from highly capable outside suppliers. Logistics resides in the service sector, according to international economists. Thus while the number of "goods" produced in this example may not change, economic activity (and employment) appears to be declining in the manufacturing sector and increasing in the service (logistics) sector. Facilitating this phenomenon has been the emergence of global air cargo TNCs including DHL, FedEx, United Parcel Service and TNT. These firms have emerged to provide end-to-end logistics services and delivery anywhere in the world within 48 hours. After constructing global networks in the 1990s, all four TNCs now operate in more than 200 countries and in 1998 DHL was named in a major survey by Global Finance magazine as the world’s most global corporation.

Whilst the ‘manufacturing matters’ argument is still evoked by social scientists (e.g. Cohen and Zysman 1987) and by policy makers, it is getting harder to determine what exactly manufacturing is as the value chain explodes! As operations are disaggregated, the manufacturing process itself becomes fragmented. Identifying the manufacturing source of a product can be increasingly complicated in a world of outsourcing and strategic alliance networks. In its extreme form, it is even possible for a ‘manufacturing’ firm to be little more than a marketing and sales enterprise, having subcontracted all of its fabrication and assembly activities. This transformation of international production challenges traditional perspectives of international business, such as Vernon’s product life cycle (1966), that view a product’s value chain as an holistic entity to be transferred to another location as it matures. Vernon recognised that growth in demand for a product has locational implications (1966; 1974). As the need to be close to the customer base decreases and concerns over production costs increase, he argued that firms are likely to move production offshore. However, Vernon failed to consider that firm structure could be transformed in such a way as to render obsolete the need for the geographical co-location of value chain functions. This may in part be due to what Ietto-Gillies describes as Vernon’s ‘concentration on the product rather than the firm’ (1992, p. 101). Consequently, Vernon and most other leading writers on international political economy and international business (e.g. Buckley and Casson 1979; Dunning 1993) were unable to envisage the fundamental changes in the nature of international production that have occurred in the internet age.

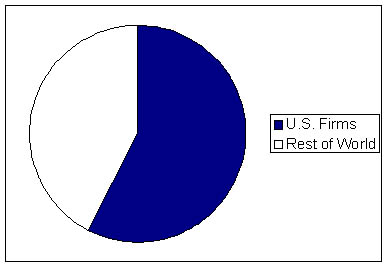

Another key Strange assertion - that the U.S. maintains hegemony over the production structure — has also weathered the test of time. Focusing on the location of the decision makers who determine what is produced, when it is produced, and the rules of engagement, yields a very different perspective than simply the location of value-added activities or trade balances. Consider the domicile of the world’s largest TNCs. Ranking the world’s largest corporations by market capitalisation — the value of publicly traded shares, which are a function of the value global investors place on current profitability and future earnings and growth potential — shows a commanding lead for U.S. firms. In The Financial Times 1998 survey of the largest global corporations, the U.S. was home to 9 of the top 10, 35 (70 per cent) of the top 50, and 244 (47 per cent) out of the top 500 firms on the basis of market capitalisation. In total, U.S. firms make up 57 per cent (7.3 trillion) of the $12.7 trillion market capitalisation of the largest 500 firms. In other words, the U.S., with about one quarter of the world’s GDP, is home to three-fifths of the market value of the most significant TNCs — the primary wealth creators in the global economy. 8 The names of the top U.S. TNCs are familiar to most people. These include Microsoft, General Electric, Exxon, Cisco Systems, Intel, and IBM. In the world of international business, market capitalisation (rather than turnover or number of employees) represents power - power to acquire other firms, raise capital, or launch new product introductions. Global shareholders, at least at the close of 1998, have placed their votes, and they believe that more than half of the world’s value creation will come from U.S.-based TNCs.

Chart 7 Market Capitalisation of Largest 500 Global Firms

U.S. Firms Make Up 57% of $12.7 Trillion Total

(Source: The Financial Times 1998 Survey)

While U.S. TNCs are as potent as ever, the U.S. government has also leveraged its power to shape the production structure. Key provisions of the GATT Uruguay Round - from the inclusion of intellectual property protection, to the General Agreement on Trade in Services - were included as a result of U.S. insistence. Strange’s perspective of international organisations as ‘strategic instruments of national policies and interests’ (1988, p. 12) is not far from the mark, based on the Uruguay Round experience. The U.S. has also acted on a unilateral basis to pursue its national interests. A good example is the U.S. conclusion of ‘open skies’ aviation treaties with over 30 countries in the 1990s, which removed capacity restrictions for international air transportation on a bilateral basis. Globally, competitive U.S. TNCs such as American Airlines and FedEx were key beneficiaries of these bilateral aviation agreements. While the focus of this chapter is on TNCs and the changing nature of international production, it is clear that the U.S. Government is sometimes an indispensable partner for U.S. TNCs in pursuing their interests.

Combining the strength of U.S. TNCs with the U.S. government, Strange’s assertion that the holder of authority in the international production structure is the international business civilisation consisting of public officials of some states, corporate managers, scientists, bankers, and market players with headquarters ‘in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles,’ (1989, pp. 262-265) remains highly relevant - perhaps more than ever as a result of changes in international production over the last decade.

Conclusion

The argument advanced in this paper is that current trends in global production make Strange’s production structure more relevant than ever for the study of International Political Economy. The emergence of the internet, combined with falling real transportation costs and a liberal trade environment, have allowed many TNCs to reconfigure their value systems and integrate operations on a truly global basis as never before. TNCs (particularly those based in the U.S.) appear to control a growing share of the world economy, and, as evidenced by the growth of trade in intermediate goods, a growing share of world trade as well. In Strange’s lexicon, TNCs have enhanced their influence on the global production structure as ‘the people who make the key decisions on what is produced, where and how, and who designs, directs and manages to sell successfully.’

While TNCs have increased their influence over the production structure, we have not analysed Strange’s contention that TNCs have enhanced their power in the international system, i.e. their ability to affect outcomes so that their preferences take precedence. 9 This is a highly complex issue that is beyond the scope of this paper. Undoubtedly the growing economic clout of TNCs, as evidenced by the FedEx / Scotland example in this essay, does translate into significant influence on policy outcomes many cases. What is clear is that TNCs and governments need each other more than ever. With the changes in international production structure that Strange first boldly described more than a decade ago, public policy creation will become an increasingly complex endeavour.

REFERENCES

Bhagwati, Jagdish (1997) in Balasubramanyam , V.N. (ed.) (1997), Jadgish Bhagwati: Writings On International Economics, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Buckley, P.J. and Casson, M. (1979) ‘A Theory of International Operations’, European Research in International Business, reproduced in Buckley, P.J. and Ghauri, P.N. (1999) The Internationalization of the Firm (London: International Thomson Business Press).

CEPD (Taiwan Council for Economic Planning and Development). (1997), The Plan for Developing Taiwan into an Asia-Pacific Regional Operations Center, Taipei: Executive Yuan.

Dicken, Peter. (1992) Global Shift: The Internationalization of Economic Activity (2nd edition), London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Dunning, J.H. (1993) The Globalization of Business (London: Routledge).

Friedman, Thomas L. (1999) The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux)

Gilpin, R. (1987) The Political Economy of International Relations (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press).

Henderson, David (1998) The Changing Fortunes of Economic Liberalism, London: Institute of Economic Affairs

Ietto-Gillies, G. (1992) International Production: trends, theories, effects (Cambridge: Polity Press).

Karliner, Joshua. (1997) The Corporate Planet: Ecology and Politics in the Age of Globalisation, Sierra Club Books.

Krugman, P. (1997) Pop Internationalism (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press).

Lawton, T.C. (1999), European Industrial Policy and Competitiveness: concepts and instruments (Basingstoke: Macmillan Business).

Porter, M. E. (1985), Competitive Advantage: Sustaining and Creating Superior Performance (New York: The Free Press)

Stopford, J. and Strange, S. (with John S. Henley) (1991) Rival States, Rival Firms: Competition for World Market Shares (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Strange, S. (1986) ‘Supranationals and the State,’ in J. Hall (ed.), States in History, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Strange, S. (1988) States and Markets, London: Pinter Publishers

Strange, S. (1988) ‘The Future of the American Empire,’ The Journal of International Affairs, vol 42, no. 1.

Strange, S. (1990) ‘The Name of the Game,’ in N. Rizopoulos (ed.) Sea Changes. American Foreign Policy in a World Transformed, New York and London: Council of Foreign Relations Press

Strange, S. (1996) The Retreat of the State, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Vernon, R. (1966) ‘International Investment and International Trade in the Product Cycle’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 80, pp. 190-207.

Vernon, R. (1974) ‘The Location of Economic Activity’ in Dunning, J.H. (ed.) Economic Analysis and the Multinational Enterprise (London, Allen & Unwin).

Womack, J.R., Jones, D.T., Roos, D. (1990) The Machine That Changed The World, New York: Ranson Associates

World Trade Organization (1997) 1997 World Trade Organization Annual Report, Vol II, Geneva.

Yeats, A. (1998) "Just How Big is Global Production Sharing?" World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper No. 1871, Washington D.C.

Endnotes

Note 1: This term is take from Paul Krugman (1996) and refers to ‘people who speak impressively about international trade [and competitiveness] while ignoring basic economics and misusing economic figures’. Back.

Note 2: For a discussion of Toyota’s lean production approach, see Womack et al. (1990) Back.

Note 3: For a discussion of Post-Fordism, see Kaplinsky, R., in Eden (1993), p. 112. Back.

Note 4: Data from speech by Michael Dell to Detroit Economic Club, 1 November 1999 Back.

Note 5: See ‘Colography Group Examines 20 Years of U.S. Air Cargo Deregulation,’ Colography Group, 22 Nov 10, 1997 Back.

Note 6: According to The Colography Group, more than $2 trillion of world trade by value moved by air cargo in 1998. An example of an Asian Country dependent on air cargo is The Philippines, where 66% of exports (by value) moved by air in 1998, according to the Philippine National Statistics Office. Back.

Note 7: The group of British air cargo carriers is known as the British Cargo Airline Alliance. For a discussion of the events surrounding this issue refer to The Journal of Commerce, 13 April 1999 and 18 March 1999. Back.

Note 8: The results of the 1998 Global 500 Financial Times Survey can be found at http://www.ft.com/ftsurveys/q3666.htm Back.

Note 9: See Strange (1996), p. 17 for a discussion on power. Back.