|

|

|

|

|

|

CIAO DATE: 6/00

The New WTO-Round and Eastern Enlargment of the EU: Overlapping Negotiations and the Role of the EU-Commission in Agricultural Policy 1

Manfred Elsig

International Studies Association

41st Annual Convention

Los Angeles, CA

March 14-18, 2000

Abstract

This paper focuses on three overlapping negotiations, namely the Berlin summit (Agenda 2000), the Seattle summit (New Trade Round) and the pre-accession negotiations with Poland (Accession). By looking at agricultural policy the paper identifies a weak and isolated Commission in relation to the Council and Member States. With the help of level-analysis, developed by Putnam, possible strategies of the main negotiators as well as linkages among issue-areas are highlighted. It is shown that linkages block rather than press negotiations ahead. In particular the paper concentrates on the Agenda 2000 negotiations and its influence on the length and scope of the other negotiations. It focuses on developments that shift win-sets over time as well as factors determining the outcome equilibrium inside the win-sets, as exemplified in the accession negotiations. The paper ends with a look at new institutionalist approaches (historical institutionalism and agent-theory) and shows that these help explain the variance of the agent's (Commission) activity in 1999 compared to its more active role played during the Uruguay-Round.

Introduction

Commissioner Fischler stated during a WTO-conference with the EU-candidate countries, which took place shortly before the third WTO ministerial conference in Seattle in December 1999, that "whatever the exact timetables for the multilateral negotiations and the negotiations on enlargement, it is probable that the two sets of negotiations will be very close together or overlap" (Commissioner Fischler, Bratislava 12.11.99).

The Seattle summit was considered a failure for many reasons 2 . The agricultural dossier (it is part of the so called in-build agenda) 3 was a particular stumbling block. Concurrently to the negotiations in Seattle, the Polish government coalition was caught up in a heated debate over budgetary issues heavily influenced by the worsening terms of trade with the EU and centered on the question of whether to increase - once more - duties on inflowing EU food products which threaten to push local products off the market. The harshness of the EU's stance with Poland on agricultural issues comes across as a demand for "shock therapy" in the structural reform of the Polish agricultural sector and has succeeded in driving public support for EU membership to lower levels as well as heavily influencing the accession talks with Poland.

Since the birth of the EU, agricultural issues have been given great priority within EU governance structures (Rieger 1996). Next to the Structural Funds, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is granted the largest percentage of the EU budget. The CAP is considered by many countries to distort trade and has been the cause for increasing international disapproval, especially because EU policies in other areas, such as services, are less trade distorting and therefore generally accepted by the international community. The expansion of the agricultural regime, originally pushed by France, Germany and the Netherlands in the 60s (Rieger 1996: 103), had reached a new high during the 80s through the accession of Spain and Portugal. While it was politically feasible under the 1988 German Council Presidency with financial support by former Chancellor Kohl to reach a mini-reform at that time, the conditions cadre had changed considerably by 1992 on both the internal and external front. Under the threat of a failing of the Uruguay-Round and rising budget imbalances (Germany had in the meantime to deal with Reunification) a reform, named by the Commissioner in office "MacSharry", was undertaken. 4

Most research conducted on the CAP-Reform was anchored in traditional neofunctionalist-intergovernmentalist theory, which concentrated on either national or supranational explanations for the outcome of European Policy-Making. 5 As researches began to search for approaches to overcome the biased concentration on either national or international factors to explain the MacSharry Reform the concept of level-game analysis was invoked. Drawing on the work of Robert Putnam (1988), international relations theorists tried to conceptually intertwine these factors into one analytical framework. The question facing them was not whether to combine domestic and international explanations into a theory of "double-edged" diplomacy, but how best to do so (Moravcsik 1993a:9). 2-level-analyis concentrates inter alia on theories of international bargaining and emphasizes the statesman as the central strategic actor. The strategies used reflect a simultaneous calculation of constraints and opportunities both from the domestic and international negotiation board (Moravcsik 1993a: 16-7). As level-game analysis, be it influenced by neofunctionalism or intergovernmentalism, lacks explanatory power for changes in the political context of European Policy-Making institutionalist, approaches and network analysis seem to gain relevance as it concentrates more on long-term developments in an institutionalized setting (Pierson 1996, Daugbjerg 1999, Pappi and Henning 1999). Similar to game-theory, two-level games are used as a heuristic tool to describe rather than directly explain factors which influene the outcomes (also Wolf and Zangl 1996). Nevertheless, on a conceptual basis it still holds an important place.

In the aftermath of the Uruguay Round, the question of whether there was a synergistic linkage between the parallel negotiations in the GATT-Regime and the CAP, which is embedded in a multi-level governance system (Jachtenfuchs and Kohler-Koch 1996, Marks et al. 1996), received considerable attention. This question has found various answers when concepts of level-games are applied. Paarlberg (1997), for instance, finds little evidence for the hypothesis of a positive link. For him, the international pressure through the GATT provided no measurable incentive for domestic reforms in the US and Europe. On the contrary, it contributed to a delay of the outcomes ("negative synergistic linkage"). 6 Patterson (1997) tested the empirical value of Putnam's two level metaphor in a three-level game and concluded that whereas the link between the Uruguay Round and EC reform in 1988 was only minimal, a considerable link was found in 1992. 7 Coleman and Tangermann, however, find that " the timing of CAP reform and the very logic of the reforms introduced represent direct responses to international pressures emanating from the GATT negotiations" (1999:386). Thus, it is generally agreed that a linkage between the two parallel negotiations, negative or positive, does exist.

Putnam's (1988) two-level game metaphor draws implicitly more attention to the negotiating actors at the intersection between domestic interests and international pressures ("negotiator in chief": COG) than strictly domestically or internationally focused research does. After having tested the two-level metaphor with various case studies, Evans asks critically concerning the level of analysis: "Has the focus on leadership gone too far, pointing research uncritically down a slippery slope that leads to the idiosyncratic, personalistic (individual) 'first image' explanations rejected by systemic realists a generation ago? (Evans 1993:428)." Nevertheless, the role of negotiator was fairly under-explored by Putnam's one-dimensional focus on its room for maneuver based solely on the influence of national interest groups and institutions (Schoppa 1993, Mo 1994). 8 Moravcsik enlarges the spectrum of the negotiator's utility function by introducing the concept of "acceptability-sets". He counters these critics to a certain degree, but at the same time shows cautiousness by limiting the negotiator's self-interested capacities (Moravcsik 1993a). 9 He opts for an unequal two-level game inspired by liberal intergovernmentalism with explanatory power given to domestic factors (1993b). For him, the main negotiator plays the sole role of mediator with restricted means of influencing stable preferences. Others, such as Coleman and Tangermann, on the other hand, advance neo-functionalist arguments and see a powerful broker and self-interested actor pursuing independent objectives (1999).

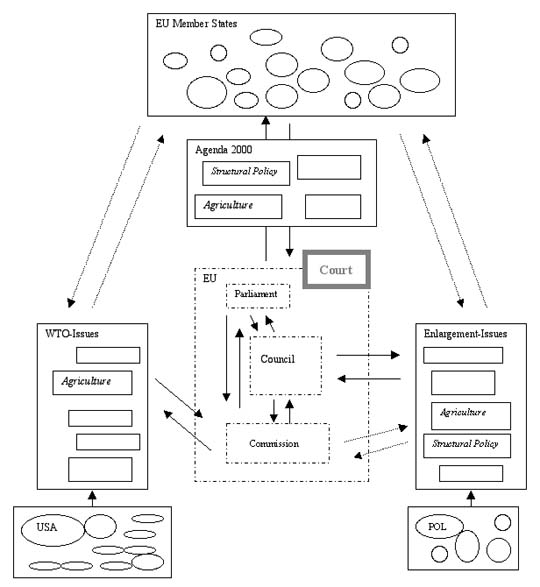

This paper expands the linkages outlined above by adding a new phenomena which overlaps with the parallelly conducted negotiations (CAP-Reform and WTO), namely the ongoing EU enlargement process. Figure 1 is a sketch of horizontal interaction clusters. The EU-System is placed in the center as the EU-Commission sits both at the negotiating table of the WTO and plays a role in the accession negotiations. Concurrently, the Commission conducts iterative games within the EU system with the Member States, the European Council and the European Parliament in the framework of the Agenda 2000 negotiations.

(Figure 1)

The paper is presented as an explorative study of European multi-level regulation by complementing level-game-analysis with a closer look at new institutionalism. First it draws on concepts developed by Putnam and reviews them critically. Then it looks at the three parallel overlapping negotiations and tries, with the help of level-analysis, to explain outcomes and discover possible linkages. In the final chapter, it will take a look at new institutionalism in an attempt to explain the passive role of the EU Commission in the three games. It hopes to contribute to a broader approach to intertwining the "horizontal interaction between issue-systems" (Collinson 1999: 220) in a post Uruguay Round perspective. In opposition to most level-analysis case studies, this paper reviews ongoing negotiations conducted parallel to the Agenda 2000 and therefore only presents probabilistic results. It draws on past experiences in these negotiation arenas. This way of proceeding is more apt to depict the inherent blockage in this process, which is otherwise under-developed in ex post approaches.

Level games, linkages and reverberation: Putnam reconsidered

The concept of level-games as an analytical approach seems to lend itself to examining the rather heterogeneous picture of multi-leveled governance as it allows a crossing of domestic and international boundaries. In order to apply level-game analysis, though, we first have to comment on possible adjustments to Putnam's metaphor. Putnam developed his analytical framework at the end of the cold war. He focuses primarily on economic issues and attempts to conceptualize linkages outside the area of security policy. Putnam was early to recognize of the growing importance of economic interdependence in world politics, phenomena discussed today as "globalization" and "denationalization". 10 The paper utilizes Putnam's concept and focuses on linkages inside the issue-area of trade, namely agriculture. 11 The focus on agriculture as the field of analysis results in domestically biased outcome explanations. The influence of transnational and supranational actors in this sector is far less weighty in comparison with other trade areas (namely services, information technology, etc.), where domestic lobbyists generally have strong international backing. Supranational actors behave rather passively, are often handicapped by, as what Scharpf calls, the "joint-decision-trap" (1988) and seem not to lobby overtly in international negotiations until they feel their intermediate goals are endangered. During the Uruguay Round, the multinationals waited a rather long period of time until beginning to defend their interests vigorously. Their action was motivated by the threat of possible discrimination on foreign markets resulting from a negative outcome of the negotiations. This threat lead to pressure on the national negotiators. 12

Methodologically, level-games seem to solve the level-of analysis problem (Singer 1961, Waltz 1959) by taking into account both domestic and international variables to explain outcomes. However, they don't address questions regarding the preponderance of power structures (pre-existing structures of interest) as such (compare Evans 1993). 13 Power resources seem to play a major role in games where the negotiating actors are not constrained by institutional settings. This is true for the accession negotiations and to a lesser degree for the trade negotiations within the WTO. 14 In the latter, institutionalized rules and norms might counter-balance power resources to a certain degree. In the accession talks, however, the lack of explicit institutionalized proceedings results in different power resources which alternatively shape the process and outcome of the game. This phenomena is inadequately explored in Putnam's work. The win-set concept does not explain what helps the negotiator restrict or enlarge win-sets. Further, the extension of the two-level metaphor to a three-level-analysis in the case of the European Union (Patterson 1997, Moyer 1993) has to be conducted with caution as the power resources of the EU institutions, namely the Commission, varies considerably over policy fields.

The empirical findings of this paper lead to a re-weighting of certain variables introduced by Putnam and make a discussion necessary. This discussion is presented in the following four points: First, Putnam's metaphor does not account sufficiently for the possibility of constraints emanating from the international arena. As mentioned above, level I institutions are only superficially mentioned by Putnam, yet they play an increasingly important role in policy coordination. 15 Patterson (1997) points to this shortcoming and shows that the GATT negotiations had no significant influence on the outcome of the 1988 EU agricultural reform package, whereas in 1992 they did. Domestic factors and the applied strategies of the negotiators are not satisfactory in explaining the ability to suddenly overcome the "status-quo default condition" (Scharpf 1988). 16 The variance in outcome can be explained by taking supranational and institutional factors into account. These factors seem to gain relevance the longer the "GATT-game" lasts and the more the negotiations come under pressure. The resulting time-induced imbalances, namely the unwillingness of actors to let a final outcome slip out of hand and a fear of a perpetuation of the status quo lead to the necessary pressure to cause policy shifts . In Putnam's case-study on the Bonn summit he attributes partial influence to international pressure. In his view, pressure from the international community created a "necessary condition" for the policy shifts (1988:430). But he attributes the outcome mainly to domestic resonance and the strategies followed by the leader. 17

Second, not only do level I institutions matter, but the procedural setting and uncertainty at level I negotiations are also important. Putnam looks primarily at bilateral and trilateral negotiations. This paper focuses mainly on multilateral negotiations in which the decision making process is primarily consensus driven. This puts the assumption into question that any key player at the international table, who is dissatisfied with the outcome, may upset the game board (Putnam 1988). Multilateral negotiations are often characterized by coalition building, making it more difficult for a key actor to credibly invoke the exit-option. Further, multilateral negotiations increase the likelihood of decision-making under uncertainty, as it becomes a challenge not only to properly assess the other's win-sets but also one's own win-set. After having tested Putnam's metaphor with the help of case-studies, Evans concludes that "the others side's domestic polities were often mistaken as well, but not dramatically more often than estimates of one's own polity" (Evans 1993: 409). Uncertainty as a key feature for explaining the outcome has been closely studied by Iida (1993) in a two-level setting and by Schneider and Cedermann (1994) to explain the variance of political cooperation in the European Community.

This leads to the third point, namely the negotiator's selection of possible strategies and his preferences, which can be modeled -in opposition to Putnam's belief - as independent from the influence of his constituencies. Schoppa (1993) and Mo (1994) criticized Putnam's view that negotiators have no real personal interests in the negotiation process and its outcome. Moravscik (1993a) introduced the so-called acceptability-set for the government's position in relation to the win-sets directly linked with the interest of the constituencies. 18 This paper focuses in the last chapter on the influence the monitoring activities of the Member States have on the Commission's acceptability-set in an agent-principal framework.

In the literature, the strategy of "tying hands" is diversely discussed. Evans concludes after comparing heterogeneous case-studies, that the "tie-hand strategy is infrequently attempted and usually not effective" (Evans 1993: 399). This paper illustrates, however, that if negotiations with the same actors over many years are conducted, the negotiators' hands are tied from the very beginning as the constituencies are capable of learning. It is generally felt that the efficiency of this type of negotiation shouldn't be underestimated. Threats of the shadow of ratification are becoming rather credible and as the case of the Agenda 2000 negotiations show, this strategy is more then ever used by negotiators. 19 On the other hand, the concept of enlarging each other's win-set in order to untie the hands of the negotiator seems overemphasized. Side-payments and target linkages can be introduced to offer special benefits to the opponents of a treaty. This strategy is sometimes used in power asymmetric negotiations, such as the accession negotiation. Another instrument is the attempt to influence through "reverberation", which is more greatly a form of symbolic policy act, such as, for exampl, the visit of a statesman to another country in order to win the other's constituencies favor. As Patterson (1997) points out, reverberation can often also end in back-flashes, making it a risky strategy. As this paper indicates, "reverberation" is more often an exception than courant normal in international trade politics. The Seattle summit showed that discussions and negotiations on international trade issues are no longer excluded to high level statesmen and are now highly influenced by groups and organizations outside the member governments, making "reverberation" as an instrument likely to end in back-flashes. The Seattle summit further indicated that the question of relative and absolute gains is back on the table. 20 Analyzing the multi-level governance of the EU also questions the assumption that policy preferences of Member States and therefore the preferences of COG are fixed (see Pierson 1996:140). Domestic policy shifts occur through elections especially in political systems dominated by two major parties or party coalitions as in Great Britain, France and Germany. This paper shows that a weakened Commission also reflects a minor policy change in the WTO negotiations.

This leads to the fourth point: a closer examination of factors representing domestic constraints for international bargaining. Not surprisingly, by studying agricultural policy, the explanatory power of domestic factors for the outcome is considerably high. Procedural settings of level II institutions, the institutional integration of pressures groups in decision-making and enforcement and their overall influence define the win-set. These factors cannot be neglected by the negotiator even though he might have personal goals diverging from the defined win-set of his constituency. The paper further finds no evidence that the internal division strengthens the negotiator's position (Putnam 1988). The European Commission does not play this strategic card. Poland's negotiators, on the other hand, try to transpose internal division directly to the negotiating table in order to build pressure. They want to be seen as the transmission belt of domestic interests rather than as a strong internal player. In the next chapter, I analyze the process and the outcome of the most important of the observed games: the CAP game.

Berlin summit: Incremental change in the CAP?

In the summer of 1997, the Commission presented its reform proposition under the title "Agenda 2000". The proposition consists of a new financial framework for the period 2000-2006 and is closely linked to a reform of the two most important expenditure areas, namely agriculture and structural policy, in view of eastern enlargement and in order to meet the commitments of the Uruguay Round. The negotiations centered around the different reform propositions in agriculture. What follows is an overview of the negotiations with the help of level-analysis by closely looking at the agricultural dossier.

The Berlin summit can be modeled as a de facto two-level game, with the international level playing a minor role. Possible "reverberation" from the international level, namely the warnings of the USA or Commission members, such as Sir Leon Brittan, were far from constructive and found no resonance in the discussion. The international level created no back-flash but actually blocked progress in the discussions. The supranational players, such as the Commission, were weakened and the domestic players shut their eyes from possible international influence.

In a level-analysis perspective, the influence of level I on the outcome seems nearly nonexistent. Pressure from the enlargement process was slightly visible and primarily presented by two respective funds (ISPA and SAPPARD), which were created in support of pre-accession efforts to aid the application countries. 21 The summit further illustrated that the Southern European countries and Ireland are unwilling to pay for the enlargement by ceding privileges, as the example of their intransigence in preserving the Cohesion Fund showed. 22 The wealtheir countries also showed little willingness to compromise as their efforts were directed towards reducing their net payments (Germany) maintaining their privileges (Great Britain's rebate) or showing little support for the CAP reform (France). The game output was also greatly influenced by the process. 23 The CAP was in the center of the deliberation with a half-hearted appeal from the finance ministers to remain within the lines of the outlined budget. 24 25 The final outcome was left to the heads of state and government, who chose to play the domestic card, leaving the communitarian card un-played. No one could afford to go home with less in the hand than they arrived with. The Berlin summit's outcome is best explained by the priority given to domestic factors. The passivity of the Commission in allowing domestic interests to take center stage at the summit seems surprising. The most striking empirical finding is that the Council even watered down the package already agreed upon by the agricultural ministers. At the same time the finance ministers were left in the rain by the Council's decision to allow increased spending. Thus, the final outcome of the Berlin summit can be largely explained through the concept of distributive games, the order of the negotiations, the passive role of the EU Commission and the non-transparent "negotiation mechanisms".

The CAP reform objectives were in the tradition of 1992 reform, which aimed to further reduce guarantied prices and lead to lower export subsidies These goals are also in line with future WTO talks as export subsidies are the most politically contested instrument of the EU's market support system. The loss of income should be compensated for through direct payments. 26 Direct payments fall under the blue box and are to be negotiated beginning in 2000, with the peace clause continuing to 2003. 27 28 Price cuts are planned for cultivated plants, beef and veal. A reform of milk quotas also put forward. An increase in the total milk quota is intended to result in lower prices for milk products and, at the same time, legalize the chronic over-production in countries like Italy. 29 The US ended direct payments to their farmers in the 1996 Farm Act. 30

A closer look at the negotiations in the three months preceding the Berlin summit sheds light on the actors' preferences. Negotiations seemed to move considerably fast and tensions increased after the German Presidency proposed a system of co-financing CAP spending. 31 This proposal rang the alarm bell in France, leading to the country's deliberate threat to leave the table. In order not to isolate itself, though, the French Agricultural Minister proposed to decrease direct payments over time to stay inside the budget line. 32 As France receives a relatively large share of EU subsidies and has one of the most competitive agricultural sectors in Europe, this offer seemed an elegant counter-proposal. However, the suggested conditions would be disadvantageous for farmers in other countries.

France's proposal opened a "window of opportunity" for the Commission. Not only would a decrease of direct-payments proposed by a member country help to control unlimited CAP spending, it would also simplify negotiations with the Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC). The Commission has been denying these countries direct payments by arguing that this form of support is considered a compensation for price cuts, which the CEEC has not suffered. The CEEC do not share this reasoning. A decrease in direct payments would also bolster the EU's position in the forthcoming WTO negotiations. Further, as the proposal emanated from a member country, the Commission would not have to bear the political costs of being responsible for a proposal reducing subsidies. Commissioner Fischler acted passively by refusing to take a stance on the controversy. He stated the Commission had not submitted a proposal for co-financing and would only do so if there was clarity on the political agenda (Agra Europe, 25.1.99). As for the model of decreasing payments, Fischler suggested an allowance of some 5'000 Euro be set, thus especially helping small farmers in Portugal (Agra-Europe, 22.2.99). The role of the Parliament in the process of bargaining was also rather limited as it is reduced to approving the overall budget.

At the Council of Finance Minister's meeting in mid February, clarification was not made as to whether the established maximum level of expenditures was to be achieved only in 2006 or whether the maximum level was to equal the average spending over a 7 year period. The often cited German-French axis suffered in the meantime from Germany's decision to go its own way in the negotiations and not consult with France. In the past, this axis represented a guarantee for continuing effective output, as a compromise between these two countries often proved a conditio sine qua non for the adoption of EU legislation at the council level. The new German government's openness to different coalitions greatly discomforted the French (FT 3.3.1999). 33 The German Agricultural Minister, Funke, tried shortly afterwards, in a surprise move, to smoothen the German-French differences. He proposed a half-hearted compromise not in the name of the Presidency but in that of Germany. 34 This had a (in)voluntary side-effect: the widespread criticism with which the proposal was met made France realize that their position was not greatly supported in Europe. On March 11, 1999 the Agricultural Ministers agreed on a package worth 7 billion Euro (314.1 billion total) over the called spending level for the 2000-2006 period. 35 The idea of a decrease of direct payments was abandoned, price cuts were lowered 36 and the reform of the dairy market postponed to 2003. Only Portugal abstained from approval during the meeting of Agricultural Ministers. Great Britain, Sweden and Denmark hoped for a stronger reform, yet were in a minority position. This package negotiated two weeks before the Berlin summit increased pressure on the heads of state, as somebody was going to have to pay for this increase. Public attention was now redirected to the structural policy reform, in particular, the Cohesion Fund and the British Rebate was questioned (FT, 22.3.99).

In the weeks before the Berlin summit, the NATO intervention in Kosovo and the search for a new President of the Commission dominated the political arena and were first on the agenda at the summit in Germany's old and new capital. Thus, the Agenda 2000 negotiations began rather late in the summit and were characterized by typical bargaining processes. The heads of state diluted the CAP reform even more. They didn't see the need to cut additional costs from the provisional agricultural agreement earlier that month. President Chirac was mainly held responsible for opening Pandora's box (FT, 26.3.99). 37 Dairy sector reforms were further delayed and price cuts for cereals further reduced. 38 These changes were only possible by simultaneously allowing side-payments to the more pro reform countries in other areas. 39 That the heads of state felt unease over the projected agricultural spending became clear in the final declaration. At the same time, they urged the Commission and Agricultural Ministers to search for additional savings. 40 The total budget is to increase from currently 89.6 billion to 103.5 billion in 2006 (Europe 21). Every country went home with a little something. 41 In the end, the slices of the stagnant grew. Meanwhile, forthcoming challenges, namely WTO and eastern enlargement, were not adequately addressed. The pre-accession funding was set at 3.12 bn annually and the money reserved in 2002 was 4.14 bn for new members, rising to 14.21 bn in 2006 (FT 27.3.99). 42 The German Presidency and other net contributing countries, such as the Netherlands, tried to cut spending for structural fund payments. The Southern Euroepan countries, however, successfully secured an increase in the structural support of poorer regions, which - until new members join the Union -benefits them the most. In the end President Chirac tried to commit the Union to using the CAP Reform as a mandate in the upcoming WTO trade round ("tie-hand"). His move was countered by the majority of the heads of state. To summarize, the chief negotiators in Berlin acted like "hawks". They tried to minimize their win-sets by (convincingly) threatening to exit the game. The German Presidency held a particular position. As they were committed to representing communitarian interests, they acted "dove-like" and therefore had to tame their own "hawk-like" intentions to a certain degree. Not surprisingly, their share of the growing cake is - at least in the short run - limited. 43 The win-sets in a multilateral arena are further diversly defined in relation to who is conducting a prognosis of the real long-term costs and benefits. Calculation on the effect of the market development of certain CAP mechanisms varied according to the author (i.e. Commission, the Court of Auditors etc.), leaving considerable room for uncertainty and interpretation. 44

The outcome of the Berlin summit is ambiguous as it places the EU Commission in a difficult and defensive position for WTO negotiations. The Commission's hands are especially tied by the failure to further cut direct aid and guaranteed prices, leading to continued high export subsidies. This leads us to assess the Commission's role during the decision-making phase as passive.

During the Uruguay Round the Commission played an active role (see Coleman and Tangermann 1999). They even threatened to take the Member States to the ECJ when the Agricultural Council failed to produce a budget in 1988. In spring 1999, the Commission looked very different. Due to the many internal struggles at the time the CAP reform was left to the Directorate-General VI (Agriculture). Even Sir Leon Brittan's skeptical remarks towards the subsidy-mechanisms seemed to fade. In light of the forthcoming trade negotiations, the dairy market reforms would have been more WTO compatible than the current policy, therefore helping the Commission. The package proposed by the Commission was, however, rather modest from the beginning. At different times, General Director of DG VI, Legras, and Commissioner Fischler even warned the negotiators not to freeze the CAP budget (Agra Europe, 18.1.1999). Fischler went so far as to call the agreement of the Agricultural Council "the most radical reform since the Common Agricultural Policy was first established in the early 1960s" (Herald Tribune, 12.3.1999).

As a closer look at the Berlin summit shows, the parallel negotiations (WTO, Accession) are often referred to in rhetoric. In daily bargaining, which focuses on immediate outcomes, the negotiations are, however, of minor importance. As Thomson shows, (1996) the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture (URAA) does not pressure the EU to reform its agricultural sector, but prevents it from further protectionist moves. Thus, international pressures did not at this time significantly reverberate within domestic or community politics. Intergovernmental negotiations are influenced, however, by the shadow of future negotiations making domestic forces tie their negotiators' hands well in advance. They define a restricted win-set from the beginning. In Berlin they were helped by a weakened Commission. By comparing the linkages in the Uruguay Round we have seen that at the end of the international trade negotiations the influence of the international level on the CAP was considerable. In the beginning, though, pressure was rather modest. Here a parallel to the Uruguay-Round can be drawn. In the next chapter I examine the Seattle summit by discussing possible linkages between the reform of the CAP and the new round.

Seattle summit: Is agriculture an underestimated stumbling block?

The WTO increasingly attracts attention from the broad western public as illustrated by the Seattle summit. Transparency issues gain importance in multilateral trade talks, therefore limiting the negotiators' ability to exploit information gaps as well as the possibility of overt side-payments. 45 The summit failed for a multitude of reasons, domestic, systemic and otherwise. However, the question of the influence of ideas on policy-making - which lost ground in the intergovernmentalist-neofunctionalist debate - has to be addressed anew (see Goldstein and Keohane 1993, Risse-Kappen 1996). New to this conference was a growing criticism of globalization; the consensus for embedded liberalism is shattering or as the economist Paul Krugman put it, world trade is confronted with an image problem (Herald Tribune, 24.1.2000). 46 Skepticism over globalization did help the European Commission, who arrived in Seattle with a broad agenda not to be pushed into the corner from the exports-pushing CAIRNS group and the US. Led by the new Trade Commissioner Lamy, Agriculture Commissioner Fischler and Commissioner Byrne (Health and Consumer Protection), the EU found itself as the main advocate for the protection of consumer interests, cultural heritage and the social role of the agricultural sector. CAP was one of the stumbling blocks and contributed to an overloading of the WTO agenda. While the European model of agriculture seemed to have been successfully defended, the stalemate which resulted from the inability to find common ground on various issues seemed like a move on the part of the Europeans to win time. A lowering of export subsidies, however, lies in the long-term interest of the EU, especially in light of eastern enlargement and interests in a balanced budget. 49

How will things proceed? The EU is not fond of a light negotiation package with agriculture taking prominent position and will try to push a broad agenda. 50 The US seems to pursue the opposite strategy. No real leverage can be expected from a WTO-Secretariat headed by a Director General who has been appointed for only a partial term. This stands in contrast to the findings of Coleman and Tangermann (1999), whose arguments were based on a strong agenda-setting role of the Secretariat, namely former General-Secretary of the GATT Arthur Dunkel .The current weak position of the Secretariat places the application of these findings in question.

What can be said at this preliminary stage of the negotiations with the help of Putnam's metaphor and the empirical evidence from the Uruguay-Round? First, as outlined above, level-games cannot methodologically account for the dynamics of multilateral trade negotiations in an institutionalized system, such as the WTO. Second, the variety of the actors and the different forecasts for the long-term effect of the changing rules of international obligations render it difficult for the negotiators to assess each other's win-set. The negotiators act therefore "hawk-like" and try to reduce their win-sets.

Reverberation does not always happen intentionally, but actors are aware of its possible effects and do not want to risk back-flashes. Not surprisingly, the European Delegation to Seattle was not accompanied by heads of state as this would have put more pressure on the negotiators from the European side. 51 The issues were handled at an abstract level, therefore side-payments were not yet a feasible strategy objective. The US negotiators' win-sets were curtailed both by by President Clinton's speeches at the conference on labor issues and the intransigence by the Republican dominated Congress against European calls to put anti-dumping issues on the agenda. As the USTR (United States Trade Representatives) already has the difficult tasks of convincing Congress to approve China's entry into the WTO while also seeking to obtain fast track approval for negotiating international trade agreements, they couldn't afford to negotiate by only looking at their acceptability-set. One could conclude that the negotiators' win-sets simply didn't overlap and that the actors incorporated possible future gains through later negotiations in their utility-assessment ("shadow of the future"). Also some signs of a "joint-decision trap" were appearing, as some countries began to prefer the status-quo from a reform process they wouldn't have enough control of (Scharpf 1988). They preferred to stay in the trap and believe that others are having greater struggles as they lack alternatives to the present multilateral trade system. The Commission continues to lack the confidence of other negotiating partners. The Uruguay Round illustrated how little freedom the Commission has in negotiations, as commitments by the Commission have to be approved by the Council, where a de facto consensus in important issues exists. 52 This approval process often results in involuntary defection on the part of the Commission, as it cannot ex post deliver what it has promised, making it an incalcuble actor. In theory, the Commission's "tied hands" mustn't necessarily be a disadvantage (see Schelling 1960, Putnam 1988). The Commission still deals with the long shadow of the disastrous experience in the end phase of the Uruguay Round when some Member States publicly attacked the Commission over exceeding its mandate.

This leads to questions regarding motives for the Commission's behavior. In the process of formulating the mandate for the EU, the Commission played a largely passive role. The long weeks of defining the mandate were largely influenced by the CAP reform. The Trade Ministers clashed for a first time in May 1999 over the strategy as countries like the Netherlands, Sweden, Great Britain and Denmark questioned the proposal that the CAP should automatically determine the EU's position (Agra-Europe, 17.5.99). At the end of the summer, the US Senate passed the new farm aid bill to increase financial assistance to farmers from 9.2 to 16.6 Bn $ for 1999 (Agra-Europe, 9.8.99). This helped EU Agricultural Ministers to move from a defensive to a more offensive strategy, attacking US food aid policy and US export credit schemes. 53 At the same May meeting, the Ministers voiced their wishes for a new trade round encompassing issues such as animal welfare and environmental protection. 54 They further defended subsidies included under the blue box. Possible room to maneuver was found only in the area of export subsidies (FT 15.9.99).

The newly appointed EU-Commission was passive in working with the Council on the formulation of the mandate. Commissioner Fischler's comments regarding work on the mandate were ambiguous. At times he praised the CAP-Reform as a huge success and as the fundament for WTO talks; 55 took a firm stand addressing the US, criticizing their export support mechanism and direct aid schemes; 56 and denied any attempt to picture a agricultural fortress of Europe. On other occasions, however, he pointed out fields of compromise and criticized the Agricultural Ministers for creating an approach which could threaten Europe's interests by providing no room for concessions (Agra-Europe, 16.8.99).

In conducting negotiations, it becomes clear that the EU-Commission still lacks necessary bargaining power. Following the Uruguay Round, the EU Commission tried unsuccessfully to turn to the ECJ (avis I/94) and later, during the negotiations which led to the Amsterdam Treaty, to gain more legitimacy and enlarge its room to maneuver in WTO negotiations. The ECJ, however, backed the Member States' position. The provisional "mixed competence" for WTO agreements in fields, such as services and intellectual property between the Commission and the Member States completely tie the Commission's hand as a negotiator. During the deliberation prior to the 1997 Ministerial Conference in Amsterdam, the Commission withdrew its original proposal as it was considered to be watered down by the representatives of Member States. The end result, by amending Art. 113, was not far off the status quo. 57 In Seattle, a move from Commissioner Lamy to propose a compromise, already backed by countries such as Japan, Korea, Norway and Switzerland, was immediately criticized by representatives of the EU Member States and the EU Parliament. At the same time, a ministerial meeting in Brussels condemned the Commission's proposal. This example illustrates how thin the Commission's room to maneuver has become in WTO issues.

To sum up, the Commission tried to take the driver' seat but failed and has since tried to stay in a comfortable situation in the back seat, acting passively with tied-hands. Linkages from the CAP were dominated by the logic not to give away everything at the beginning. On the other hand, accession played little role in the Commission's strategy, even though Commissioner Fischler repeatedly hinted at a possible link. The WTO-Secretariat proved rather weak in its efforts to facilitate a breakthrough of the negotiations and will have to try to rebuild its reputation inside the IGO at a micro level through confidence building. In this light, it seems that Coleman and Tangermann (1999) are too optimistic in focusing on the Secretariat's role. By only looking at the outcome, they neglect the long lasting and often blocked negotiations, where domestic factors repeatedly got the upper hand. Further, as Hall (1993) already shows in his study, the framework of ideas influences the policymakers beyond the simple setting of policy goals and the choice of instruments to achieve them. Ideas in form of value systems further help legitimize the status-quo and protect it form changes (another form of Scharpf's "status-quo default condition" (1988)). Coleman (1998) shows in his comparative study between the US, France and Germany for the years 1955-85 that this idea framework which strongly developed in the European states represented a considerable obstacle for a paradigm shift from protected agriculture toward market liberalism (see also Skogstad 1998).

Poland's Accession negotiations: Do Berlin and Seattle matter?

Directly after the Berlin summit the Polish government decided to increase import duties for EU products on various agricultural products, starting 1.4.99. 58 Pressure from the farm lobby had built up due to falling prices mainly influenced by growing (export-subsidized) imports from the EU. The decision was legitimized by the safety-clause formulated in the Europe Treaties (Agra-Europe, 29.3.99). This move triggered speculation about the chosen moment, two days after the closing of the Berlin summit. This policy decision exemplifies that the question is not whether the processes of CAP-Reform and Eastern Enlargement are entangled but how. The EU-Commission has also been pushing for a coordinated action with CEEC countries in the WTO arena, a wish that Commissioner Fischler hasn't tired in publicly stressing. The average measure of support (AMS)-limits in agriculture for the CEEC are very low in comparison to the those of the EU (see Thomson 1996). After the accession of the applicant countries to the EU, renegotiations with their main trading partners will be necessary, as a custom union under WTO-law is only exempted from principles such as the most-favorite nations clause, if countries loosing their market share through growing import duties or the like are compensated adequately for their loses. 59

Unlike the WTO negotiations outlined above, the enlargement negotiations differ as their total failure is not politically feasible. The question is therefore not, whether cooperation will take place, but how the terms of accession will look. The political process of accession began in 1993 at the Copenhagen Council meeting, where is was agreed that "the associated countries in central and eastern Europe that so desire shall become members of the European Union". It was decided in Luxembourg in December 1997 that the screening process would begin on 31 March 1998, under the auspice of the Commission. 60 The Berlin summit made 22 billion Euro available for pre-accession support during the period 2000-2006 and reserved some 57 billion Euro in the EU's 2002-2006 budget for possible first accessions from 2002 onwards. This sum was considered by almost all observers to be insufficient. On 13 October 1999, the Commission recommended that the Member States open negotiations with more countries. 61 This suggestion was endorsed by the Member States at the Helsinki summit on 12 December 1999. Chapters expected to be opened with the first group of accession candidates under the Portuguese Presidency are: inter alia Agriculture, Justice and Home Affairs, Freedom of Movement of Persons. By the end of the Portuguese Presidency, all negotiating chapters will have been opened, allowing for a complete overview of the hard core negotiating issues to be solved with each of the applicant countries.

How are the negotiations expected to proceed? The Commission proposes common negotiating positions for each chapter relating to Community competence (i.e. agriculture). The Council President in cooperation with all Member States and the Commission, suggest negotiating positions for chapters concerning the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) as well as justice and home affairs. 62 The positions require unanimous approval by the Member States. The Presidency of the Council puts forward the negotiating positions agreed upon by the Member States and chairs all negotiating sessions. The General Secretariat of the Council and the applicant countries provide the Secretariat for the negotiations. The negotiations are conducted by representatives of the Member States and the applicant countries. In conclusion, a draft is sent to the Council for approval and the European Parliament for assent. The ratification of the Treaties of Accession is needed by each Member State.

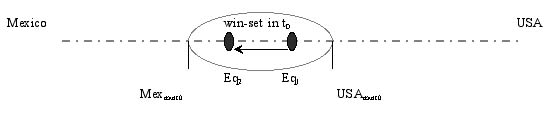

Without entering the debate on the overall gains and loses of the EU enlargement process, a look at the negotiations between the EU and Poland in the agricultural sector shows to what extent power resources, strategies of "tied-hands" and the linkages from parallel overlapping processes can determine the win-sets of each side. One critique on the two-level game metaphor is the empirical weakness of negotiations between two or more parties with considerable differences in power resources. The few empirical studies on this issue have produced different findings. In their case-study on the 1988 Brazilian Debt Negotiations with the IWF, Lehman and McCoy (1992) conclude that the weakness of the Brazilian government was turned to a strategic negotiation advantage by reducing its win-set by the credibly threat of instability. Avery's case-study (1996) on the NAFTA negotiations between the US and Mexico, on the other hand, highlights how domestic pressure and the election of a new president in the stronger state can lead to a re-opening of the negotiations at level I. The study shows that ex-post negotiation processes, like ratification, matter insofar as the president has to win a majority which he does through different forms of side-payments. Uncertainty characterizes the negotiations at level I (see Schneider and Cedermann 1994) as US negotiators cannot ex ante calculate all possible obstacles in the ratification process. 63 A big change of the balance of power in level II institutions, namely the election of a new president (Clinton follows Bush) further moved the outcome equilibrium inside the existing win-sets from Eq1 to Eq2 as Figure 2 shows.

Figure 2

In the case of the accession negotiations, factors which influence the position inside the common win-sets (i.e. uncertainty, changes in level II institutions, negotiation strategies) can be supplemented by factors shifting the win-sets over time, namely market developments under the influence of status quo regulations. Possible market developments include a loss of market share for Polish products and greater pressure on Polish farmers to leave the farming sector. As the European Agreements already allow privileged market access for agricultural products from the EU, the once protected Polish market has been confronted with new challenges. The inflow of EU products profiting from export subsidies along with struggling export markets in Russia have driven the prices in Poland down and the domestic market has become over-saturated. 64 At the beginning of 1999, 25% of the working population in was employed at least part-time in approx. 2.4 m farms throughout the country. 65 Farmers enjoy a generally positive image in Poland, partly due to the strong stand they took against the former communist regime. 66 In order to make Polish agriculture compatible in the Common Market, the Ministry of Agriculture introduced plans to raise the efficiency of larger Polish farms, provide incentives for those who sell out and help fund early retirement. A further initiative on the part of the Ministry of Agriculture is to encourage investment in non-farm rural development such as tourism. The cost of these programs totals some 19 billion Euro over the next 7 years. The EU will pay a third of the costs (FT 9.9.99).

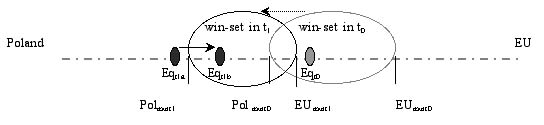

Until now, EU negotiators have been refusing Poland's call for direct payments. 67 The Agenda 2000 budget makes only a limited amount of funding available for direct payments to the CEEC. If the EU were to pay the same amount of subsidies in form of direct payments to Polish farmers as it does to current EU farmers, it would increase agricultural expenditures by 4 bn Euro. If Polish products continue to lose market shares and Polish farmers do leave the farming sector , the EU and the Polish win-sets will shift on the scale as shown below in Figure 3. The longer the negotiations last, the further the win-sets move to the left. 68 This shift makes possible the danger that the new negotiation equilibria (Eqt1a) moves outside the minimal point of acceptance (Polmint1). The EU will therefore attempt to shift the possible negotiation equilibrium within the Polish win-set (Eqt1b) by offering side-payments such as the pre-accession schemes described above.

Figure 3

As mentioned above, the position inside the win-sets can be influenced by strategy (i.e. side-payments) and its effects, which can only be analyzed ex post. At this stage, we are confined to looking at possible instruments employed during the pre-negotiation period before the official negotiations begin in April 2000. Budget restraints limit the Polish government in its ability to influence domestic constituencies. Poland's agricultural subsidy rates are the lowest in Europe and are about half the EU levels (FT 9.9.99). 69 The government is rather "weak," as the Solidarity Electoral Alliance (AWS) is currently plagued by internal struggles over the direction of its policies. Its instability threatens to jeopardize the stability of its coalition with the Freedom Union, the junior partner led by finance minister Balcerowicz. The budget deficit in 1999 was around 6% of GDP while pensions and social security expenses were on the rise. Throughout the year, the polls showed extremely alarming figures of declining support for the AWS. 70 Street protests by farmers in August were directed against the import of cereals. The farmers demanded both greater subsidies and state guarantied purchase schemes (Agra-Europe, 16.8.99). In September 1999, 50'000 Poles, among them many farmers, demanded an easing of restrictive economic policies in one of the largest demonstrations since the fall of communism (FT, 25.9.99). Level II developments tie the hands of Polish negotiators and reduce the size of their win-sets. As such, the Polish negotiators cannot afford to make any concessions in the field of direct support as they (especially the AWS) have to think about reelection. From the beginning, the Polish Ministry of Agriculture acted "hawk-like", hoping to receive support from the European capitals. As Lehman/McCoy showed in the Brazilian example, weak governments try to portray themselves as pro-market actors but are dependent on outside support to consolidate reforms at home. One way of doing so is by picturing the danger of a blockage of reforms if the government is replaced by another one. In the case of Poland, a trend towards a negative perception of EU membership was underpinned by opinion polls showing that about 55 per cent of all Poles would vote yes in a referendum on EU membership (support has declined from about 80 per cent five years ago) (FT, 9.9.99). How credible this threat is can, at this stage, not yet be assessed. Jerzy Plewa, Deputy Agricultural Minister, publicly criticized the EU position on direct payments not allocated to Polish farmers. The EU Commission continues to deny CEE farmers direct payments by arguing they have not suffered price cuts, but the Polish government recently introduced direct payments to wheat producers, who were badly hit by declining prices. This contested policy move in the government sends a signal to Brussels (FT 9.9.99) demonstrating the Polish farmers suffered price-cuts and therefore are also eligible for subsidies. The Financial Times commented in a September 1999 article that Poland was heading "for a clash with the EU" on the direct payment issue by trying to ease domestic pressure and at the same time apply pressure on Brussels to review its stance on the issue (FT 21.9.99). The Polish Agriculture Ministry threatened to increase tariffs for various agricultural imports, i.e. for wheat from 3 to 27.5%. 71 They argued that this policy option was necessary to protect Polish farmers and legitimate according to their rights and obligations under the WTO. As Poland has a maximum tariffs agreement with the organization, but has applied rates far below the maximum to help develop a market economy, it has the right at WTO member to increase them. This increase, the agriculture ministry further argued, would create extra negotiating room in forthcoming tariff-reduction talks in the next WTO-Round. This was not only criticized by the EU-Commission but also by the Finance Ministry fearing that higher tariffs lead to more inflation. The stability of the Polish government was threatened several times in the second half of 1999 due to internal disagreement on this issue. In December the EU-Commission warned the Polish government publicly to increase tariffs (Agra-Europa, 2.12.1999). 72 The Polish government still has not stopped rejecting the idea of transition periods for the agricultural sector (Central Europe Online, 7.12.1999). Kulakowski, the Chief Negotiator for Poland not only criticized a proposal from the Commission President Prodi to postpone Poland's entry date from 2003 to 2004 but also said that "the backing for the accession process is stronger in theory than in practice" (Central Europe Online, 16.12.1999).

Instruments such side-payments are likely to be used in this kind of negotiation, where the loser of the process and the swing-voters needed for the support of the defined policy can be identified. Side-payments, such as co-financed programs, are used by the EU to enlarge the win-sets of Poland. Side-payments to EU Member States not favoring enlargement are being distributed constantly (see Agenda 2000). Poland tries to please farmers through tariff increases and subsidies. The swing voters, it seems, have not yet been addressed (see Avery 96:124). "Reverberation" is also likely to be a often used strategy by the negotiation parties as the symbolic part of the deal is extremely high valued. This has to be observed closely in the future negotiations to understand possible moves and outcomes.

As outlined above, the Commission's role in the accession negotiations was initially more of an agenda-setter and later of an arbitrator with the power of information. Interestingly enough, the Commission supported the policy of a uneven membership in direct aid in agriculture from the beginning. Inside the Commission, the DG VI (Agriculture) plays an important role as it has already shown through its actions and in-actions that it can induce a shift in policy reform in the Agenda 2000 negotiations. Not surprisingly, the head of the EU Commission's task force for accession, Nikolaus van der Pas, appreciated the pre-accession help but criticized the CAP-Reform. He identified "direct payments" as a hot issue (Agra-Europe, 17.5.1999). Commissioner Fischler countered critics of export-subsidies to the CEEC by arguing that without them other importers would "close the cap" and the deteriorating terms of agricultural trade were not due to subsidies but rather the inability of the CEEC to increase their exports to Western Europe (Agra-Europe, 26.4.1999). This wasn't the end of the story. Fischler changed his view as depicted by his actions. Due to the worsening of terms of trade between the CEEC and the EU, he proposed a quota system with the CEEC and the abolition of export subsidies (Agra-Europe 12.7.1999). This proposal was followed a week later by a decrease in export subsidies for pork directed to the CEEC. The balance of the EU Commission's politics towards enlargement could be further altered through the recent establishment of DG Enlargement, headed by Commissioner Verheugen. How can this rather hard-line stance on the issue "direct payments" be explained? Why didn't the Commission, as agenda setter, choose to propose equal treatment? Why was the Commission so inactive? These questions will be discussed in the concluding chapter.

Can New Institutionalism resolve the puzzle?

As presented above, the use of level-analysis becomes difficult when applied to the European Union. Level-analysis focuses very strongly on the chief-negotiators. External EU negotiation responsibilities are often shared, making it difficult to speak of a single voice. 73 Three periods have to be distinguished to better understand the impact of the actors inside the EU polity: first the agenda-setting (initiating), second the negotiating process and third the adoption of a negotiated package (ratification). Only by taking a look at the whole period can the Commission's role in a policy field be assessed. This paper has further emphasized the passive role of the Commission and its inability to make use of its power resources. Until early 1999, the Commission had greatly influenced the ongoing process towards eastern enlargement and was very active in maintaining necessary marge de maneouvre for future trade diplomacy. How can the change in influence be explained? Here institutionalist approaches might fill out the gap, be they in the historical (Pierson 1996, Bulmer 1998, Ikenberry 1994) or in the rational-choice tradition (Pollack 1996, 1997).

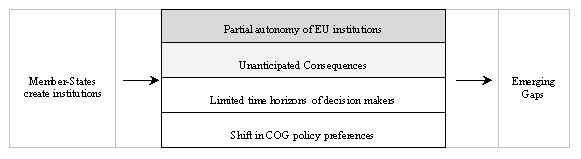

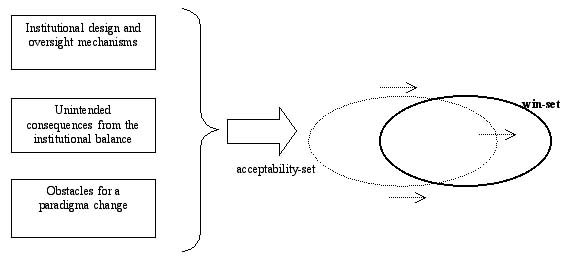

In outlining his theory of historical institutionalism, Pierson (1996:131) begins from the premise that social processes cannot be understood without acknowledging the impact of historical processes. Historical Institutionalism shows how institutions (i.e. Commission) can change over time and conduct autonomous policies. By doing so they drift away from the goals set by the designers (Member States) representing their long-term interests. 74 In his excellent article Pierson identified four possible groups of factors that might explain why such gaps would emerge (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

From the different variables above only the degree of autonomy of the institutions (i.e. Commission) can be identified as a key factor for its passive or active role in this case-study. What Pierson refers to as "unanticipated consequences, emanating from issue density", such as asymmetrical access to information, helps shape the autonomy of the institutions as it is closely linked to possible negotiation instruments for the Commission. A shift of COG's preference at level II seems not to have occurred in agricultural policy, as its structure seems robust against changes in the domestic level. To give an example, the change of the Prime Minister in France has - if at all - a minor impact on a possible shift in French Agricultural Policy. The COG's decisions, even when focused on short-term calculations, namely to please electorally important constituencies, do not vary considerably from long-term calculations. Thus, the limited time horizon of decision-makers does not at first glance influence the possible gap or non-gap. The original design of CAP already had all the inherent characteristics Scharpf identifies as "joint-decision traps" and is therefore kept hostage to the Member States.

The change in partial autonomy could explain the shift of the Commission's role. Let's now turn to the question of "what", then, has an effect on the variance of the autonomy. With the help of principal-agent approaches, made fruitful for European policy analysis by Pollack, a first attempt to answer this question shall be made. In the European context Member States (principals) did "pool sovereignty" to an upper level (Keohane and Hoffmann 1991) and equip their agents with autonomous instruments to ensure efficient decision-making. Thus, the political organs of the EC are not without resources. As a result, they are not simply passive tools of the Member States (Pierson 1996:132). The question, then, is why isn't the Commission using their resources? As Collision points out, "the allocation of institutional responsibility provides only a partial, and sometimes quite misleading, picture of the nature and location of power and agency in the system" (1999:208). Thus, even though the Commission has de facto autonomy it doesn't profit from the opportunities to further enlarge the gap. In contrary, its acceptability-sets in negotiation seem to overlap or move further towards overlapping with the collective win-set greatly influenced by Member States strongly opposing reforms. As figure 5 shows three major explanatory variables can be portrayed.

Figure 5

Institutional design and oversight mechanisms

The institutional design from the beginning was not favorable for changes in the field of agricultural policy. The absence of a trade council ,especially evident during the Uruguay Round, transfers a disproportionate amount of influence to the Agriculture Council. If divisions in the General Affairs Council of Foreign Ministers exist, sectoral councils can shape policies considerably (Moyer 1993). Further, the shared competency for negotiating in the WTO weakens the Commission and leads to passive negotiating. However, the Commission is able to learn and anticipate moves from the principal to sanction offensive moves. The oversight mechanisms developed by Pollack (1996, 1997) can explain why, in the case of the Commission, it didn't "take on a life of its own". Oversight procedures can themselves be separated in "monitoring" and "sanctioning". Taking a look again at the case of trade negotiations in the GATT, the Member States possess a type "police-patrol oversight"(Pollack 1996) with the so-called Art.113 Committee. This Committee not only acts as a monitor but at the same time influences the setting of negotiation mandates (Comitology). Agricultural Policy generally foresees a "management committee procedure", where the specialized Committee can use a qualified majority vote to direct a proposal by the Commission to the Council. 75 The strong national farm lobbies complete the monitoring (so-called "fire-alarm oversight") and directly pressure their national representatives at the European table. Sanctioning instruments in the EU are limited in an agent-principal framework. As a result, the agent can only be subjected to limited sanctions should he drift, in spite of monitoring, from the target set by the principal. Most likely, the revision of an agent's mandate or, as in the case of the Amsterdam Treaty, the non-attribution of necessary bargaining power can be seen as a tough sanction. The oversight mechanism and the institutional setting alone, however, do only partly explain the passive role of the Commission. Two further explanatory factors are described below.

Unintended consequences from the institutional balance

Pierson describes how unanticipated consequences widen the agency losses. The opposite could also be true as another institution, such as the parliament (half agent, half principal) can intervene in the game in the form of sacking the Commission for mismanagement and neputist activities, as was the case in 1999. Such developments are not determined by the Member States. The Court's actions also are only marginally monitored. As described in the previous chapter the negative opinion of the Court concerning the Commission's sole legitimacy to negotiate in the WTO (I/94) was a major blow for the Commission. The Court was usually described as the natural ally of the Commission. 76 By creating different agents, the principals didn't have to use strong sanctioning measures to call on the Commission. An emerging competition between the agents can to some degree block their actions. In light of these developments, the agent tries to secure Member States' support by avoiding "bureaucratic drift".

Obstacles for a paradigma change

The importance of "ideas" shouldn't be underestimated as they are embedded in institutions (Skogstad 1998). The CAP has been an important component of European Integration since its creation. State intervention was seen as a necessary policy tool in the early years of the EC to avoid food scarcity. Through the massive growth of production-related subsidies, import-restrictions and export subsidies, the EU became a major exporter of agricultural products. In the past years - influenced by budget imbalances and outside pressure (GATT) - the EU began to lower tariffs and subsidies. The paradigma change from a protected to a more liberal market, despite encountering various obstacles in Europe (Colemann 1998). A protectionist sentiment among Europeans (also the ones paying higher prices) is emerging towards protecting European produce, European farmers from cheap imports, and traditional European production methods and farm traditions. The BSE crisis further encouraged consumers to buy local. This "corporate culture" doesn't stop outside Brussels. Inside the Commission in general, and in the DG VI in particular, ideas of protecting European Agriculture have influenced the Commission's stance on international trade issues. As the Seattle summit demonstrated, diverging interests within the Commission seem to become united when pressure from the outside intensify.

Bibliography

Avery William P. 1996. "American agriculture and trade policymaking: Two-level bargaining in the North American Free Trade Agreement." Policy Sciences 29(2):113-36.

Bulmer Simon J. 1998. "New Institutionalism and the Governance of the Single European Market." Journal of European Public Policy 5(3):365-86.

Coleman William D. and Tangermann Stefan 1999. The 1992 CAP Reform, the Uruguay-Round and the Commission: Conceptualizing Linked Policy Games. Journal of Common Market Studies 37(3):385-405.

Collinson Sarah 1999. "'Issue-systems', 'multi-level games' and the analysis of the EU's external commercial and associated policies: a research agenda." Journal of European Public Policy 6 (2):206-24.

Evans Peter B. 1993. "Building an Integrative Approach to International and Domestic Politics." In Double-Edged Diplomacy, Peter B. Evans, Harold K. Jacobson and Robert D. Putnam (eds.). Berkeley: University of California Press, 397-430.

Daugbjerg Carsten 1999. "Reforming the CAP: Policy Networks and Broader Institutional Structures." Journal of Common Market Studies 37(3):407-28.

Goldstein Judith and Keohane Robert O. 1993. "Ideas and Foreign Policy: An Analytical Framework." In Ideas and Foreign Policy, Judith Goldstein and Robert O. Keohane (eds.). Ithaca & London: Cornell University, pp. 3-30.

Griego Joseph M. 1988. "Anarchy and the Limits of Cooperation. A Realist Critique of the Newest Liberal Instituionalism." International Organization 42(3):485-507.

Hall Peter A. 1993. "Policy Paradigms, Social Learning and the State." Comparative Politics 25:275-96.

Iida Keisuke 1993. " When and How Do Domestic Constraints Matter?" Journal of Conflict Resolution 37(3):403-26.

Jachtenfuchs Markus and Kohler-Koch Beate 1996. Europäische Integration. Opladen: Leske&Budrich.

Keohane Robert O. and Hoffmann Stanley (eds.) 1991. The New European Community. Boulder: Westview Press.

Lehmann Howard P. and Jennifer L. McCoy 1992. "The Dynamics of the Two-Level Bargaining Game. The 1988 Brazilian Debt Negotiations." World Politics 44(4):600-44.

Marks Gary et al 1996. "European Integration from the 1980s: State-Centric v. Multi-level Governance." Journal of Common Market Studies 34(3):341-78.

Mo Jongryn 1994. "The Logic of Two-Level Games with Endogenous Domestic Coalitions." Journal of Conflict Resolution 38(3):402-22.

Meunier Sophie 2000. "What Single Voice? European Institutions and EU-U.S. Trade Negotiations." International Organization 54(1):103-35.

Meunier Sophie and Nicola'ïdis Kalypso 1999. "Who Speaks for Europe? The Delegation of Trade Authority in the European Union." Journal of Common Market Studies 37(3):477-501.

Moravcsik Andrew 1993a. "Introduction." In Double-Edged Diplomacy, Peter B. Evans, Harold K. Jacobson and Robert D. Putnam (eds.). Berkeley: University of California Press, 3-42.

Moravcsik Andrew 1993b. "Taking Preferences Seriously: A Liberal Theory of International Politics." International Organization 51(4):513-53.

Moyer Wayne H. 1993. "The European Community and the GATT Uruguay Round: Preserving the Common Agricultural Policy at All Costs." In World Agriculture and the GATT, William P. Avery (ed.). Boulder & London: Lynne Rienner, pp. 95-120.

Paarlberg Robert 1997. "Agricultural Policy Reform and the Uruguay-Round: Synergistic Linkage in a Two-Level Game?" International Organization 51(3):413-44.

Pappi Franz U. and Henning Christian H.C.A. 1999. "The organization of influence on the EC's common agricultural policy: a network approach." European Journal of Political Research 36:257-81.

Patterson Lee Ann 1997. Agricultural Policy reform in the European Community: a three-level game analysis. International Organization 51(1):135-65.

Pierson Paul 1996. "The Path to European Integration. A Historical Institutionalis Analysis." Comparative Political Studies 29(2):123-63.

Pollack Mark A. 1996. "The New Institutionalism and EC Governance: The Promise and Limits of Institutional Analysis." Governance 9(4):429-58.

Pollack Mark A. 1997. "Delegation, agency, and agenda setting in the European Community." International Organization 51 (1):99-134.

Pollack Mark A. 1999. "Delegation, agency and agenda setting in the Treaty of Amsterdam." European Integration on-line papers (http//eiop.or.at/eiop)

Putnam Robert D. 1988. "Diplomacy and domestic politics: the logic of two-level games." International Organization 42(3):428-60.

Rabinowicz Ewa 1999. "EU enlargement and the Common Agricultural Policy: Finding compromise in a two-level repetitive game." International Politics 36(3):397-417.

Rieger Elmar 1996. "The Common Agricultural Policy: External and Internal Dimensions." In Policy-Making in the European Union. Helen Wallace and William Wallace (eds.) Oxford: Oxford University Press, 97-124.

Risse-Kappen Thomas 1996. Exploring the Nature of the Beast: International Relations Theory and Comparative Policy Analysis Meet the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies 34(1)53-80.

Scharpf Fritz W. 1988. "The Joint-Decision Trap: Lessons from German Federalism and European Integration." Public Administration 66(3):239-78.

Schelling Thomas 1960. The Strategy of Conflict. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Schneider Gerald and Cedermann Lars-Erik 1994. "The change of tide in political coooperation: a limited information model of European integration." International Organization 48(4):633-62.

Schoppa Leonard J. 1993. "Two-level games and bargaining outcomes: why gaiatsu succeeds in Japan in some cases but not others." International Organization 47(3):353-86.

Singer David J. 1961. "The Level-of-Analysis Problem in International Relations." World Politics 14:77-92.

Skogstad Grace 1998. "Ideas, Paradigms and Institutions: Agricultural Exceptionalism in the European Union and the United States." Governance 11(4):463-90.

Snidal Duncan 1991. Relative Gains and the Pattern of International Cooperation." American Political Science Review 79(4):701-26.

Thomson Kenneth J. 1996. "The CAP and the WTO after the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agiculture." European Foreign Affairs Review 2:169-83.

Waltz Kenneth N. 1959. Man, the State, and War: A Theoretical Analysis. New York: Columbia University Press.

Webber Douglas 1998a. "High midnight in Brussels: an analysis of the September 1993 Council meeting on the GATT Uruguay Round." Journal of European Public Policy 5(4):578-94.

Webber Douglas 1998b. "The Hard Core: The Franco-German Relationsip and Agricultural Crisis Politics in the European Union." European University Institute, Working Paper RSC No 98/46.

Wolf Dieter and Zangl Bernhard 1996. The European Economic and Monetary Union: "Two-level Games" and the Formation of International Institutions." European Journal of International Relations 2(3):355-93.

Zangl Bernhard 1995. "Der Ansatz der Zwei-Ebenen-Spiele." Zeitschrift für Internationale Beziehungen 2(2):393-416.

Zürn Michael 1998. Regieren jenseits des Nationalstaates. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Endnotes

Note 1: This paper is part of a Ph.D. project on linkage politics in the EUBack.

Note 2: i.e. no new trade round was launched; the transatlantic partners were not able to find common ground before and during the summit on issues such as agriculture, competition and health concerns; the proliferation of wishes directed to the young international governmental organization (IGO), not least by developing countries, made it impossible to create some sort of compromise platform for further trade liberalization.Back.

Note 3: The in-build agenda was decided in 1995 and foresees the beginning of further liberalization as well as talks in the field of agriculture. Even without a new trade round, this subject has to be addressed from 1999 onwards.Back.

Note 4: For an excellent summary see Patterson 1997 Back.

Note 5: For intergovermentalist approach, see Webber (1998a), for neofunctionalist-supranational approach, see Coleman and Tangermann (1999).Back.

Note 6: Paarlberg looks at the influence of the GATT-Uruguay Round on agriculture reform in the EU and the US. He finds the Round to have had some influence on the 1992 MacSharry reform and almost no influence on the US reforms of 1990 and 1995-6. He identifies bilateral pressures from the US on the EU as the main international factor influencing negotiation outcomes. The EU had agreed to concessions in an earlier round (Dillon-Round), which the US wanted to see implemented under the threat of sanctions totaling $ 1 billion. Back.

Note 7: Patterson introduced another level (communitarian) parallel to the national and international level.Back.

Note 8: For a discussion on the concept of win-sets, see Putnam (1988:435-52).Back.

Note 9: According to Putnam (1988) "win-sets" are defined by domestic preferences, coalitions and institutions as well as negotiators' strategies at the international board. "Acceptability-sets", however, also mean the COG range of acceptance, which could differ from the win-set, i.e. a negotiator for personal reason rejects a compromise even though his constituencies would back it.Back.

Note 10: See Zürn (1998) for a discussion of the concept of denationalization. Back.

Note 11: In the case of EU-accession the context of European Security Policy shouldn't be neglected (see Rabinowicz 1999).Back.

Note 12: Kohl's change of position during the GATT-negotiations in the Uruguay-Round can be partly attributed to growing pressure from the export industry, which did not want to let the negotiations fail because of the agricultural dossier (Webber 1998a).Back.

Note 13: Waltz (1959) also uses three levels. Besides systemic and domestic, he applies the level of the individual statesman.Back.

Note 14: For different findings, see Lehmann and McCoy (1992), who show in their case study on debt restructuring between Brazil and the IMF that not just external power preponderance can be a advantage but also internal weakness of the government. The case study, though, is insofar biased as the IMF was heading for a compromise anyway and therefore widened Brazilian win-sets accordingly. Back.

Note 15: In Putnam's terms level I stands for the international, level II for the domestic level.Back.

Note 16: The status-quo default condition describes a lock-in situation where an agreement is unlikely as the status quo is preferred by a blocking minority.Back.