|

|

|

|

|

All Resources: Economics of TerrorismNBER "Insurance, Self-Protection and the Economics of Terrorism" by Darius Lakdawalla and George Zanjani (PDF, 28 pages, 328.5 KB)

MERIA - Political Economy of the Middle East Terrorism by Matthew A. Levitt (PDF, 17 pages, 98.8 KB)

The Economics of Civil War, Crime and Violence

In recognition of the devastating economic consequences of violence in developing countries, the World Bank has launched a large research program to study "The Economics of Civil War, Crime and Violence." The project is under the direction of Paul Collier, Research Director at the World Bank, and Ibrahim Elbadawi, member of the Development Economics Research Group (DECRG) and the Africa Department. Norman Loayza, DECRG, is coordinating the project's focus on crime and crime-related violence.

The 'About' page includes a detailed project overview and a description of the project's analytical approach. The 'Library' page lists all the studies produced by the project. The studies are also listed under separate 'Sub-topics'.

The 'resource persons' page contains short bios and contact information for the people associated with the project as well as links to their papers for the project.

This web site will be updated regularly and additions to it will be announced through the electronic newsletter. We encourage the newsletter's dissemination and we would encourage you to subscribe to it at the 'newsletter' page. If you have further questions or have information that you believe should be included in our site, please contact Marta Reynal-Querol at mreynalquerol@worldbank.org, core research group member and editor of the newsletter and the website.

Appendix F -- Countering Terrorism on the Economic Front

Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the US Government has taken a number of steps to block terrorist funding.

On 23 September 2001, for example, the President signed Executive Order (EO) 13224. In general terms, the EO provides a means to disrupt the financial-support network for terrorists and terrorist organizations. It authorizes the US Government to designate and block the assets of foreign individuals and entities that commit, or pose a significant risk of committing, acts of terrorism. In addition, because of the pervasiveness and expansiveness of the financial foundations of foreign terrorists, the order authorizes the US Government to block the assets of individuals and entities that provide support--financial or other services--or assistance to, or otherwise associate with, designated terrorists and terrorist organizations. The EO also covers their subsidiaries, front organizations, agents, and associates.

The Secretary of State, in consultation with the Attorney General and the Secretary of the Treasury, has continued to designate foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs) pursuant to section 219 of the Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended. Among other consequences of such a designation, it is unlawful for US persons or any persons subject to the jurisdiction of the United States to provide funds or material support to a designated FTO. US financial institutions are also required to retain the funds of designated FTOs.

A few 2003 highlights follow:

* On 9 January, the United States designated Lajnat al-Daawa al Islamiyya, a Kuwaiti-based charity with links to al Qaida, after France submitted this charity's name to the UNSCR 1267 Sanctions Committee (Sanctions Committee) for worldwide asset freezing.

* On 24 January, the United States designated two key members of Jemaah Islamiyah, Nurjaman Riduan Isamuddin (a.k.a. Hambali) and Mohamad Iqbal Abdurrahman (a.k.a. Abu Jibril). Both names were also listed by the Sanctions Committee.

* On 30 January, under the authority of both the EO and the FTO, the United States designated Lashkar I Jhangvi, which was involved in the killing of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl. The Sanctions Committee also included this group on its consolidated list.

* On 20 February, the United States designated Ansar al-Islam--a terrorist group operating in northeastern Iraq with close links to and support from al-Qaida. The group was added to the Sanctions Committee list four days later.

* On 29 May, the United States designated the Al Aqsa Foundation, a major fund-raiser for HAMAS.

* On 22 August, the United States designated six top HAMAS leaders (Sheik Ahmed Ismail Yassin, Imad Khalil al-Alami, Usama Hamdan, Khalid Mishaal, Musa Abu Marzouk, and Abdel Azia Rantisi) and five HAMAS-supporting 172 charities (Comite de Bienfaisance et de Secours aux Palestinians, Association De Secours Palestinien (ASP), Palestinian Association of Austria (PVOE), Palestinian Relief and Development Fund (Interpal), and Sanibil Association for Relief and Development).

* On 19 September, the United States designated Abu Musa'ab al-Zarqawi, a terrorist with ties to al-Qaida, Asbat al-Ansar, Ansar al-Islam, and Hizballah who provided financial and material support for the assassination of a US diplomat and was cited in the international press as a suspect in the bombing of the Jordanian embassy in Baghdad. Germany and the United States submitted his name jointly to the Sanctions Committee.

As of 18 December 2003, the total number of individuals and entities designated under EO 13224 is 344. The US Government has blocked more than $36.5 million in assets of the Taliban, al-Qaida, and other terrorist entities and supporters. Other nations have blocked more than $100.3 million in assets.

Wise Trade Policy Can Address the Roots of Terrorism

The West needs to open the trade door to the Muslim world

Edward GresserIn effect, as most of the world has debated globalization, these countries have conducted an experiment in 'de-globalization.' Their share of the global economy has contracted by 75% in a generation - and the generation in question is a very big one.

Since 1980, the population of the Middle East has jumped from 175 million to 300 million. That of Muslim south and central Asia has gone from 225 million to 360 million. Thus a quarter of a billion young people are fighting for opportunities no more extensive than those their parents had in the 1970s.

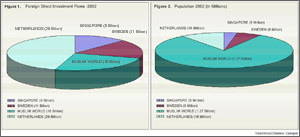

Chart 1. Muslim World: A Lot of People, Little FDI (Foreign Direct Investment Flows - 2002) Enlarge ImageIt is not surprising that a large pool of unemployable young people makes easier recruiting for radical and fundamentalist groups. The region's multiple conflicts, ethnic feuds, and religious tensions make the situation all the more explosive. And since the turn of the century, sensational coverage of these issues by a rapidly multiplying web of Internet sites and satellite TV networks has been raising the temperature even higher.

Even carefully developed trade policy cannot reverse these trends. But just as the series of multilateral trade agreements under the GATT system helped reverse the western 'de-globalization' of the 1930s, a movement towards fairer, open markets could help Muslim economies. For the moment, however, most of the Muslim world is in a state of economic inertia.

Local policies are at the heart of the problem. Nationalist economic policies, long abandoned in Southeast Asia and Latin America, continue to isolate countries from one another and the larger global economy. High trade barriers are one example: Syria's auto tariff, for example, is 200%, despite the fact that Syria makes no cars. The proliferation of sanctions and boycotts in the last twenty years, whatever their political motives, has further speeded regional fragmentation. Jordan's King Abdullah II has described the result as a 'series of isolated islands of production." And the Muslim world, despite its influence over energy markets, participates less in global trade policymaking through the WTO than East Asia, Latin America or sub-Saharan Africa.

Such policies, though, are neither immutable realities nor irreversible choices. Europe's majority-Muslim states -- especially Turkey but also Albania and Bosnia -- have a different approach, seeing their destiny in democratization and integration with the European Union. In Southeast Asia, meanwhile, Indonesia and Malaysia are big exporters and influential WTO members. In the Middle East, smaller countries like Jordan, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain are lively policy innovators. Pakistan has been revamping its policies as well, and the recent end of sanctions on Afghanistan and Iraq (and perhaps soon Libya) should help these countries and their neighbors.

Americans and Europeans have an obvious stake in the success of Muslim-world reformists. But their current policies not only fail to respond with help, but in some ways make their work harder.

European farm policies are one example. Subsidies to olive oil producers in Spain, Italy and Greece, for example, total about $2 billion a year -- more than twice the value of world olive oil trade outside the EU -- push down the price of European olive oil and keep competitive and high-quality oil from Morocco and Tunisia off the world market.

America's free trade agreement and preference network is another. These initiatives now excuse 67 developing countries in Africa and Latin America from tariffs. The unintentional result is to put Muslim-world exporters at a disadvantage. American retail stores pay no tariffs on a T-shirt made in El Salvador, Lesotho, or Peru, but a 20% tariff if they choose to buy the same shirt from plants in Pakistan, Egypt, or Turkey. The pressure will only rise next year, when the end of textile quotas enables India and China to take full advantage of their size and economies of scale.

The current American response is a proposal floated by the Bush Administration for a U.S.-Middle-East Free Trade Area. In one sense, this may be an overly ambitious approach. The difficulty of completing a Free Trade Area of the Americas, among a group of generally like-minded democracies with few internal conflicts, shows how hard any such initiative can be. In another sense, it is not ambitious enough. Even if it succeeds, its tentative conclusion in 2015 delays any tangible action for over a decade, and in excluding Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan and Central Asia, it misses countries of central importance in the war on terrorism. The more realistic short-term attempt to build free trade agreements with Bahrain and Morocco is better, but these two countries account for only about 35 million of the region's 700 million people.

An easier, and at least in the immediate future more effective, response would be to return to the approach Dawood suggested three years ago. Congress has already proposed such an idea. Last fall, Senators Max Baucus and John McCain, along with two Democratic Representatives, introduced a bill to drop tariffs on goods from 18 Muslim countries, from North Africa to Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh. Presidential candidate John Kerry had suggested such an approach even earlier, calling for "a general duty-free program for the region, [like] the Caribbean Basin Initiative and the Andean Trade Preference Act."

Such an approach could help spark quick investment and job creation. At minimum, it would improve a trade regime actually tilted against US allies in the war on terror. With a duty-free zone in place, future US Administrations would have a positive foundation to build upon as they consider carefully how to craft deeper and more comprehensive approaches to trade relations with the Muslim world. It's a pity the US didn't act on Minister Dawood's request three years ago. But there's still time to start now.

Edward Gresser is Director of the Progressive Policy Institute's Project on Trade and Global Markets.