|

|

|

|

Ozone Discourses: Science and Politics in Global Environmental Cooperation , by Karen T. Litfin

| In our modern societies, most of the really fresh power comes from science - no matter which - and not from the classical political process. |

| -Bruno Latour, The Pasteurization of France |

In chapter 1, I presented a deductive argument in support of a reflectivist approach to international environmental politics. In essence, I argued that the dominant approaches, neorealism and neoliberal institutionalism, fail to grasp the nonmaterial nature of knowledge-based power; nor do they dig beneath the surface to explore the process of interest formation. In this chapter, I reexamine this question in light of the case study, asking whether existing theories of regime formation can account for the development of the international regime for ozone protection. The central importance of knowledge in international environmental negotiations as both a political resource and an arena for struggle suggests that conventional theories are inadequate, at least for this issue area. This chapter examines the dominant theoretical approaches to international regime building as a mode of entry into the larger question of knowledge and political power. All of these, from structural realism to bureaucratic politics to interest group approaches, neglect the role of intersubjective understandings as the basis for international cooperation.

As if in reaction to past materialist excesses, a good deal of attention has recently been given to ideas and information as sources of foreign policy and international collaboration. 1 While much of that literature focuses on political and economic ideologies, some of it looks at scientific knowledge as a foundation for international cooperation. The Montreal Protocol, characterized by a high level of involvement by atmospheric scientists, seems at first glance to be an ideal case for applying the epistemic communities approach. Building upon the theoretical arguments advanced in chapter 2, however, I show in this chapter why the global ozone regime was not the work of an epistemic community.

Instead, I argue for a discursive practices approach that sees knowledge and power as mutually interactive. The power of competing knowledges - likely to be decisive under conditions of scientific uncertainty - was the critical factor. An emphasis on discursive practices, rather than on states, bureaucracies, or individuals, would interpret international regimes as loci of struggle among various networks of power/knowledge. In contradistinction to the epistemic communities approach, issues of framing, interpretation, and contingency are central to this approach.

If those scholars who discern a trend toward a postindustrial or informational world order are correct, then this argument has important implications not just for environmental issues but more generally for the nature of power in the emergent global system. One trend may be the diffusion of the sovereign power of nation-states to nonstate actors and the proliferation of disciplinary micropowers. Consistent with this diffusion would be the displacement of power toward those actors most proficient at controlling and manipulating informational resources. As is already evident in the global warming debates, the implications of this trend for relations between information-rich and information-poor nations are both intriguing and unsettling. In any case, it is not clear that politics in a postindustrial world is likely to be any less conflictual than in the past.

Alternative Approaches to Regime Formation

Neorealism has relatively little to say about regime creation in general and even less about global environmental regimes in specific. According to Kenneth Waltz (1979), the structure of the international system shapes both the most significant aspects of nations' interests and the outcomes of their interactions. The distribution of capabilities - in particular, military capabilities - is the key element of structure. Yet military force seems quite irrelevant to environmental preservation. The structure of the international system, until recently a bipolar one, tells us little about national interests or bargaining outcomes for environmental problems. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of bipolarity had no apparent effect, except perhaps in a few details, on the evolution of the ozone regime.

Those structural theories that posit a unipolar rather than a bipolar system fare no better. Neither of the two versions of hegemonic theory offers a satisfying account of the ozone regimes. The first attributes regimes to a hegemonic power acting altruistically to supply a public good, while the second sees them as imposed upon weaker states by a dominant power. 2 Both versions associate regime creation with the existence of one dominant nation. Yet the recent period of intensive environmental regime building, beginning in the early 1970s, coincides with what most observers regard as a period of dwindling U.S. hegemony and a diffusion of power (Kennedy 1987; Rosecrance 1986; Keohane 1984). Admittedly, the theory does not maintain that great powers are sufficient for international collaboration, yet the timing of the recent increase in environmental regime formation suggests that they are not even necessary.

Keohane and Nye have proposed a more disaggregated "issue-structural" model of hegemonic stability theory that applies under conditions of "complex interdependence" (1977:50Ð52). For certain issue, they argue, military force is beside the point, power is not fungible, the line between international and domestic politics is blurred, and transnational actors may be as important as nation-states. The distribution of capabilities for a specific issue, or the structure of the subsystem, may differ from the overall structure of the international system. For instance, although Brazil and Malaysia are not global powers, they are dominant actors for the issue of tropical deforestation.

Because international environmental problems are characterized by complex interdependence, it makes sense to apply Keohane and Nye's model. Yet one is immediately confronted with a mix of theoretical and empirical obstacles. Even for a narrow issue area, there is no straightforward method for gauging the distribution of power. Taking the case of the Montreal Protocol, one could argue that, since the USA and the EC each accounted for about 30 percent of the CFC market, there was no single dominant power. With a rough balance of power between two adversaries, hegemonic stability theory might incorrectly predict that no meaningful agreement would be reached.

A different tack would be to argue that because most research on stratospheric ozone was generated in the United States, there was indeed a scientific hegemony in the technical debates. Clearly, without the United States pushing for a virtual phaseout of CFCs, there would have been no reason to move beyond the freeze or the cap on production capacity initially favored by the EC, Japan, and the Soviet Union. Yet this argument cannot explain the ends to which the United States applied its superior access to scientific knowledge. Why, for instance, did it not employ scientific discourse in support of a weak treaty? Nor can it explain why the U.S. negotiating position was so compelling, even for those with strong material interests to the contrary. Nor does it explain the leadership role of other countries during the treaty revision process. An adequate account must move beyond structure to an examination of the dynamics of discursive power and the strategies of specific agents.

At the core of these difficulties lies the failure of structural approaches to examine the nature and constitution of state interests. Once a state's interests are determined, it will, of course, use its resources, technical and otherwise, to further those interests. The truly engaging question, however, is how those interests are constituted - a question about which structural theories are essentially mute. As Stephen Haggard and Beth Simmons observe, "structural theories must continually revert in an ad hoc way to domestic political variables" (1987:501). And since information and ideas generally enter into the policy-making process via domestic politics, this means that structural theories tend to neglect these factors as well.

The failure of structural approaches to consider the nature and origins of national interests is rooted in their ties to the "choice-theoretic" tradition (Oye 1986). Once the state is accepted as a rational, unitary actor, many of the most significant political questions are swept under the carpet. While a choice-theoretic approach permits an abstract analysis of the potential for cooperation in strategic situations, it provides little insight into the determinants of those situations and therefore into the question of how often or under what conditions nations will cooperate (Wendt and Duvall 1989:56). The ozone case demonstrates that actors' interests, and thus the structure of the games they play, are shaped by the knowledge they accept. Because of the flaws in their underlying assumptions, choice-theoretic approaches routinely disregard the impact of knowledge on behavior. The assumption of stable preferences that can be neatly ordered conflicts with the many cases where interests and preferences are at issue. And the persistence of uncertainty subverts the assumption of perfect information. Not only can uncertainty confound efforts to assign probabilities to alternative ends and means, it can even hinder agreement on what the proper ends and means should be.

The fact that the state seldom acts as a unitary actor further complicates matters. William Zimmerman claims that only two types of issues are amenable to a structural approach that treats the state as a rational unitary actor: those that threaten vital national interests and those that have little impact on domestic interest groups and bureaucracies. After Theodore Lowi, he calls these "the poles of power and indifference" (Zimmerman 1973; Lowi 1967). As it turns out, however, relatively few issues fall into either of these categories.

International environmental problems are among the vast majority of issues lying somewhere between the poles of power and indifference. They are the cumulative result of many local actions by domestic actors, and international agreements addressing them entail new regulations by national governments. Thus, any analysis in this area must incorporate domestic-level processes. As Harold and Margaret Sprout argued at the dawn of the environmental movement, a key ramification of environmental problems is the "progressive convergence of domestic and external politics" (1971:10).

The two traditional ways of looking at the impact of domestic actors on foreign policy are through bureaucratic politics and through interest groups, the first being state-centered and the second being society-centered. Clearly, both have something to contribute to an understanding of international environmental politics in general and the ozone regime in specific. Among the primary actors in the ozone negotiations were national agencies, various industries, and environmental pressure groups.

The bureaucratic politics model claims that actors' policy stances are largely determined by their organizational post - as the truism goes, "where you stand depends upon where you sit" (Allison 1971:176). Rather than being the result of rational analysis by a unitary governmental actor, national decisions are the outcome of internal wrangling among competing agencies with conflicting interests. In the United States, for instance, intense struggles over ozone policy found their way up to the cabinet level, with many of the competing agencies taking fairly predictable positions. The EPA advocated strong control measures, both before and after Montreal, that would have enhanced its own power as a regulatory agency. The State Department's Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs took a similar position, which can be interpreted as an attempt to raise its status from an obscure outpost to a potent diplomatic force. As the world's preeminent research agency for ozone science, NASA certainly had much to gain from the heightened sense of public concern that accompanied the international negotiations. Because regulations may be costly, at least in the short run, the Office of Management and Budget's resistance to them was consistent with its role as guardian of the government's purse strings. The Department of Energy initially opposed stringent CFC reductions because insulating foams made with CFCs had become an important component of the agency's energy conservation program since the mid-1970s. Until 1987, the Pentagon opposed regulation of the halons because they were necessary for a certain type of fire-extinguishing equipment. As the primary governmental advocate for U.S. industry, the Commerce Department predictably opposed a stringent Montreal Protocol.

The same pattern is observable in other countries and among international organizations. As a bureaucratic politics approach would anticipate, the principal ministries advocating a stringent ozone regime were environmental agencies, while those associated with industrial interests tended to resist strong measures. In those countries where industry-related agencies were most influential, namely Britain, France, and Japan, the governments were slowest to back stringent controls on CFC emissions. The global status of UNEP, not to mention its budget, would be enhanced by a strong Montreal Protocol, so there is nothing surprising in UNEP's role as principal catalyst for the ozone regime.

While the overt power of an agency, a function of its budget and other material resources, is an important indicator of its influence in the policy process, another source of influence is its access to information. The bureaucratic politics model suggests that agencies can shape foreign policy by virtue of their ability to select the information that is given to top political leaders (Art 1973:467). Indeed, this was an important dynamic in the ozone negotiations, where a group of knowledge brokers was able to control, frame, and interpret much of the information disseminated to both domestic and foreign decision makers.

But the bureaucratic politics approach leaves some important questions unanswered, each of which points to the distinctive role of knowledge and beliefs in formulating policy. It cannot explain why the influence of particular agencies waxes and wanes over time. Why, for instance, was the EPA, a relatively small U.S. agency, able to dominate the ozone policy process, while its voice was barely heard for several years in discussions on greenhouse gases? Moreover, as an exercise in comparative statics, the bureaucratic politics model has little to say about why the positions adopted by a particular agency vary over time. It cannot account for the dramatic shift in the EPA's stance on CFC reductions between the early Reagan years and 1986, a shift that occurred primarily because of the different attitudes toward risk-taking of EPA administrators Anne Gorsuch and Lee Thomas. Likewise, the bureaucratic politics model alone cannot explain the different positions taken by the various national environmental ministries.

Psychological attitudes and philosophical orientations are at least as important as bureaucratic position in determining actors' policy stances. The differences between Gorsuch and Thomas, for instance, cannot be reduced to bureaucratic position. Along the same lines, in many cases the preferences of certain officials could not be determined by their positions. Why should Donald Hodel, secretary of the interior, have been so vehemently opposed to regulating CFCs? Nor is there any obvious bureaucratic explanation for why French environmental officials differed so widely from their Scandinavian counterparts. To answer these questions, one must consider cognitive factors.

The bureaucratic politics model ignores the distinctive role of knowledge; persuasive ability is not determined by institutional position but by the power of alternative discursive practices. The EPA's ability to prevail during the domestic interagency review process was undeniably due more to its discursive competence than to any conventional measure of bureaucratic prowess. When scientists did propose specific policy recommendations, their influence was due to their persuasive ability and their status as authoritative experts rather than to their bureaucratic position.

An interest group approach suffers from the same shortcomings. While interest groups were important actors, the global ozone regime was not primarily the result of bargaining among or pressure from those groups. Rather, expert knowledge and specific modes of framing that knowledge were critical mediators of the ultimate outcomes. The main antagonists were industry and environmental pressure groups, with industry being the more overtly powerful of the two. Throughout the regime-building process, many of the proposed control measures were actively opposed by industry, especially before substitutes became available.

The influence of environmental NGOs was substantially related to their ability to frame and manipulate information. During the Montreal Protocol bargaining process, environmentalists in the NRDC employed the chlorine-loading methodology to promote an 85 percent reduction of CFCs. Later, they publicly ridiculed Donald Hodel's personal protection plan by pointing out the pitfalls of framing the issue narrowly in terms of skin cancer. After Montreal, environmental groups became more influential, and they learned that influence flowed from the ability to define the issues. In the aftermath of Montreal, they became quite savvy in the employment of scientific discourse. Friends of the Earth and other groups always framed their positions and criticisms in terms of the scientific assessments. Recognizing the universal appeal of scientific discourse, these groups rested their claims to legitimacy on the persuasiveness of their arguments, rather than on the appeal of their ideals or their ability to mobilize human and material resources. Thus, without taking into account the political implications of scientific discourse, an interest group approach alone does not contribute much to an understanding of the evolution of the ozone regime.

The argument that discourse may be an integral factor in the policy process is related to the broader claim that ideas and other cognitive factors are important determinants of social processes. After several generations of emphasis on the material causes of action and events, international relations scholars are expressing a renewed interest in nonmaterial factors. Yet because the recent research stresses "the political influence of the content of ideas, not cognitive processes" (Goldstein 1988:182), the origins of ideas are often ignored. The discursive approach taken here suggests that ideas should not be taken as independent variables in explaining policy outcomes. If knowledge and interests can merge even in the natural sciences, how much more pronounced is this entanglement likely to be for trans-scientific issues?

Any attempt to treat scientific knowledge and political power in the ozone case as either a purely independent or a purely dependent variable would ultimately generate a false picture of the events that transpired. Both theoretical argumentation and empirical research indicate that knowledge and power should be understood as interactive and that science and politics function together in a multidimensional way. There is nothing novel in these observations; they are consistent with a long tradition in the social sciences that explains events in terms of the interaction of material interests and ideas. Max Weber, for instance, wrote that: "Not ideas, but material and ideal interests, directly govern men's conduct. Yet very frequently the 'world images' that have been created by ideas, have, like switchmen, determine the tracks along which action has been pushed by the dynamic of interest" (1958:280).

Inasmuch as institutions "reflect a set of dominant ideas translated through legal mechanisms into formal governmental organizations" (Goldstein 1988:181), the literature on ideas as an impetus for foreign policy echoes the work of neoliberal institutionalists. Consistent with the study of the ozone regime, "critical junctures" are "unanticipated and exogenous events that drive institution-building" (Ikenberry 1988:233). The most commonly studied crises in world politics are economic depression and war, which tend to become "watershed events in states' institutional development" (Skowronek 1982:10) by challenging the capacity of the old institutions to cope with the new situation. But environmental crises like the discovery of the Antarctic ozone hole also frequently spur new national and international institution building.

By challenging old institutions, and hence old patterns of thinking, crises clear a space for the consideration of new ideas on how to explain and solve problems. A moment's reflection on the history of environmental problems reveals that disasters are frequently the prelude to new regimes. The 1986 Chernobyl disaster and the ensuing negotiations to update the nuclear accident regime under the International Atomic Energy Agency are a case in point (Young 1989a). Similarly, two giant oil spills in the late 1960s, one from the grounded Torrey Canyon off the British coast and the other from an oil well run amok near Santa Barbara, California, led to a complete revision of the international regimes governing marine pollution (M'Gonigle and Zacher 1979:17). The massive forest death in West Germany in the early 1980s caused that country to change its acid rain policy radically, precipitating similar moves across the Europe, even though the forest death had not been conclusively linked to acid rain (Wetstone 1987). The importance of crises for catalyzing environmental regime formation bodes poorly for problems that develop more gradually, such as loss of biodiversity, tropical deforestation, and global climate change, even if the resulting damage may be huge and irreversible.

Ideas about environmental problems are rooted in two categories of beliefs that are at least analytically distinct: causal and normative beliefs. The former would include the belief that CFCs deplete the ozone layer, whereas the latter would include the belief that, in the face of scientific uncertainty, one should err on the side of caution. 3 Scientific knowledge about environmental problems is concerned with testable beliefs about causal relations, and the authority of scientists derives from their presumed expertise about causal relations in a specialized area of study. Epistemic communities are networks of experts who share knowledge about causal relations as well as a common set of normative beliefs about preferred policies. Under conditions of uncertainty, it is argued, and especially during crises, epistemic communities become the catalysts for international regime formation. What distinguishes epistemic communities from interest groups is their shared commitment to causal in addition to normative beliefs.

The literature on epistemic communities makes an important contribution to a reflectivist understanding of world politics by focusing on social agents who are united by virtue of their shared intersubjective understandings. In problematizing interests, this literature moves beyond the constraints of structural and choice- theoretic approaches. Reflective approaches do not necessarily supersede other theoretical orientations - certain institutional preconditions may be conducive to the emergence of epistemic communities or particular discursive practices - yet by highlighting knowledge and beliefs, reflective approaches open up new research vistas beyond the study of bureaucracies and interest groups.

Nonetheless, as argued in chapter 2, the epistemic communities approach tends toward the modernist belief that science transcends politics, that knowledge is divorced from political power. While proponents of this approach are more careful than their functionalist predecessors to qualify their conclusions about the ability of science to make politics more rational and less conflict-ridden, ultimately they seem to share an underlying commitment to the rationality project. 4 Epistemic community approaches underestimate the extent to which scientific information simply rationalizes or reinforces existing political conflicts. Just as interesting as epistemic cooperation, and perhaps even the norm under the conditions of uncertainty that characterize environmental decision making, may be epistemic dissension.

While epistemic community approaches make an extremely important contribution in their attempt to elucidate the process of interest formulation in light of prevailing knowledge claims, they offer only a partial picture of the policy process. As the ozone study demonstrates, actors may revise their conceptions of their interests when presented with new information, but their receptivity to information is itself a function of their perceived interests. Knowledge and interests are mutually interactive, a possibility that epistemic community approaches downplay.

The power of epistemic communities allegedly rests on their privileged access to consensual knowledge, but both the nature and the role of consensual knowledge are ambiguous. It seems almost tautological to argue that a group of policymakers who agree on the facts is more likely to agree on policies than a group that does not. More interesting - because they are unexpected - are those instances when consensual knowledge disintegrates under political pressure (Miles 1987:37), or when ignorance, not knowledge, increases the chances of cooperation (Rothstein 1984:750). The process of negotiating the international ozone regime raises some of these counterintuitive possibilities. A body of consensual scientific knowledge may exist, yet the wide range of possible interpretations of that knowledge may limit its influence.

The two prevailing accounts of the ozone regime rightly focus on the pivotal role of scientific knowledge in shaping the outcome, but they accept science and scientists as unproblematic catalysts in the process (Haas 1992b; Benedick 1991). According to Benedick, "First and foremost was the indispensable role of science in the ozone negotiations. . . . Scientists were drawn out of their laboratories and into the negotiation process" (5; emphasis in original). But interpretation and contingent events determined the knowledge that was accepted by the various actors. In emphasizing the involvement of scientists, both accounts clash with the fact that virtually no atmospheric scientists, especially prior to Montreal, were willing to make specific policy recommendations. Beyond putting the issue on the agenda initially and framing the problem in terms of chlorine loading during the treaty revision process, scientists were not directly responsible for the ozone regime. The "power of problem definition" almost never remains with the scientists throughout the policy process (Weingart 1982:80).

Scientific knowledge, rather than the scientists themselves, was crucial, but its ability to facilitate international cooperation was mediated by two crucial factors. First, the science was framed and interpreted by a group of ecologically minded knowledge brokers associated with the EPA, NASA, and UNEP. Second, the context of the negotiations, defined in large part by the discovery of the Antarctic ozone hole, determined the political acceptability of specific modes of framing the scientific knowledge. Both Benedick and Haas wrongly downplay the impact of the hole on the Montreal Protocol negotiations. No body of consensual knowledge, either from the computer models or from empirical observations, indicated that major cuts in CFC emissions were necessary in 1987. Only one specific mode of framing the available knowledge supported such a conclusion, and that mode gained its plausibility from the heightened sense of risk that accompanied the discoveries over Antarctica. The importance of the chlorine-loading methodology is underscored by the fact that it became the universally accepted scientific discourse once the Antarctic ozone hole was conclusively linked to industrial sources. Discursive strategies were also prominent in the discussions of the environmental effects of UV-B radiation and substitute availability.

The critique of the epistemic communities approach suggests that the relationship between science (and scientists) and policy (and policymakers) is multidimensional. Scientists may join together in an epistemic community to influence the course of policy, but their power is circumscribed by a host of contextual factors. Policymakers may co-opt or manipulate the scientists, or they may simply ignore what the scientists have to say. Whether or not the voices of scientists are audible may depend upon seemingly extraneous contingencies beyond the control of either scientists or policymakers. Furthermore, the scientists may deliberately refrain from addressing the policy implications of their research.

Once produced, knowledge becomes available to a host of political actors. Knowledge brokers exploit the discursive nature of science and politics, framing the available knowledge in ways that promote certain policies. To a greater extent than the notion of epistemic communities, the concept of knowledge brokers connotes the competitive and conflictual dimensions of knowledge claims in the policy arena. Knowledge brokers may work for government agencies, industry, international organizations, or nongovernmental organizations; in the ozone case, they were found within all of these. If they come from domestic agencies, as did those associated with the EPA and NASA during the ozone negotiations, the distinction between the domestic and international levels becomes blurred. Knowledge brokers are influential political actors not because they possess superior material resources but because of their discursive competence. In the evolution of the international ozone regime, political power often emanated from the ability to set the terms of discourse.

Discursive competence depends on many factors besides the skill of the individual knowledge brokers, including the nature of the audience and context. It is not supremely consequential who these individuals are; their authority is often more a function of their ability to manipulate information than of their professional or bureaucratic credentials. More important than the specific identities of the agents of discourse is the content of discourse. As determinants of what can and cannot be thought, discourses delimit the range of policy options, thereby functioning as precursors to policy outcomes.

Consider, for instance, how the dominant antiregulatory discourse on ozone was supplanted by a discourse of precautionary action. This discursive shift occurred both domestically within the United States and internationally during the Montreal Protocol negotiations. The 1986 WMO/NASA report defined the scientific parameters of discourse, yet the heteroglot nature of that document is evident in the wide range of policy stances derived from it. One of the key properties of discourses is their capacity to define how issues are connected within an issue area (Keeley 1990:94). During the ozone talks, the politically messy climate issue was essentially excluded from policy discourse, even though it was a central concern of scientific research. Skin cancer was highlighted in the early years but downplayed later as it became necessary to attract the support of countries not concerned about skin cancer. Even the discourse of cost-benefit analysis, institutionalized in order to bolster an antiregulatory approach in the United States, was used by the proregulatory forces to strengthen their own position. As an emerging counterdiscourse came to dominate the field, the definition of permissible issue linkages shifted.

There is no easy method of correlating bureaucratic or professional identity with policy stance. Rather, what was important in the ozone negotiations was the structure and content of discursive practices, a subject that is easily ignored when the roles of specific agents is overemphasized. The particular identities of the knowledge brokers associated with the chlorine-loading methodology, for instance, may be noteworthy, but they tell us little about how that mode of framing the science gained its authoritative status. By contrast, an approach that takes discursive practices as central can say something meaningful about the legitimation process.

Most importantly, discourses define the menu of possible policy options. Chapter 4 maintains that the rise of discourse of precautionary action was primarily shaped by the discovery of the Antarctic ozone hole - despite the negotiators' explicit agreement to ignore it. By presenting the real possibility of unprecedented catastrophe, the hole shifted the terms of the debate in favor of those who preferred to err on the side of caution. Indeed, the hole changed the meaning of caution altogether; the vulnerability of ecosystems suddenly became more salient than the vulnerability of CFC industries. Thus, a discursive practices approach runs counter to any analysis of the Montreal Protocol process that downplays the discovery of the Antarctic ozone hole on the grounds that the negotiators had agreed not to consider it. This is precisely the sort of decontextualized analysis offered by Benedick and, to a lesser extent, Haas. Even a cursory glance at the press coverage during that period confirms that the Antarctic hole was at the forefront of public consciousness. And a more in-depth investigation into the perceptions of key scientists and officials indicates that the hole was very much on their minds. Under such conditions, the hole's discovery naturally had a strong influence on the dominant discursive practices.

Initially, it might seem as if the argument that crises empower counterdiscourses is little different from the neoliberal institutionalist observation that crises generate new ideas and, hence, institutional change. The key difference, though, is that the discursive approach goes beyond the institutional expressions of ideas, moves into their deeper structure and content, and explores how these are conditioned by context. This approach puts the focus on discursive practices, rather than on individuals or organizations. Unlike institutionalism, which tends to accept ideas and power as separate independent variables, it understands power as being embedded in discourse. Discursive practices are not free-floating entities; they are embodied in technical processes, institutions, and pedagogical forms that both impose and maintain them (Foucault 1977:200).

A discursive practices approach offers insights into political process that go beyond those generated by a purely materialistic approach. Environmental crises, for instance, are not just physical phenomena; they are informational phenomena as well. New information is incorporated into previously existing discursive practices, or else it is employed by knowledge brokers to empower counterdiscourses.

A poststructuralist perspective on international regimes yields very different sorts of insights and research questions from those emanating from liberal and realist approaches, both of which treat interests and rationality unproblematically. Putting the spotlight on discourse enriches these key concepts, just as it yields a more complex picture of power and social order. Realists tend to define power narrowly in terms of material resources; they explain regime formation in terms of the interests of the preponderant power. Regime analysis rooted in more liberal assumptions about the international system tend to assume that regimes are communitarian, benevolent, voluntary, and cooperative. The conventional notion of regimes as "principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures around which actors' expectations converge" connotes ideas of freely shared judgments, freely converging to a consensus (Keeley 1990:83Ð85). A discursive approach to regimes, however, offers a more variegated conception of power than that of the realists, and it assumes a more skeptical stance to the problem of community and order than that of liberal institutionalists.

A discursive practices approach regards international regimes as localized power/knowledges, with each regime providing an arena for contestation among contending discourses. Arguing on behalf of such an approach, James Keeley states,"Adding knowledge to power and treating a regime as an implementation of both, this analysis goes inside the regime rather than treating it as a mere dependent variable. It is, therefore, better able to ask how regimes work and what they do and to incorporate cognitive issues into both its questions and its answers" (1990:100; emphasis added). Such an approach is particularly germane to the study of regimes in which the framing of information is decisive, as is often the case in environmental regimes. It also anticipates that regimes tend to become arenas for debate among competing power/knowledges, as the Montreal Protocol has been during the treaty revision process.

After stating the advantages of a discursive approach, it is only fair to acknowledge its methodological shortcomings. A discursive approach is helpful in answering "how" and "what" questions, but it does not fare as well in providing parsimonious explanations. (Recall, however, that approaches purporting to offer more parsimonious explanations have already been called into question earlier in this chapter.) Moreover, because of the central role it gives contingency and context, a discursive approach cannot make sweeping generalizations or offer precise predictions.

What, then, is it good for besides telling a story well? First, many would see inherent value in a well-told story, particularly if the topic were related to planetary sustainability. But I would also argue that a well-told story can offer important insights into the policy process in general and perhaps into future events as well. It can alert the analyst to certain misconceptions that might arise, and it can also alert the practitioner to the importance of alternative discursive strategies.

Implications for Global Environmental Politics and the World System

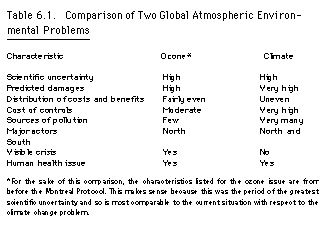

Because the global ozone regime has been lauded as a prototype for a future climate change regime, it is worthwhile to draw some comparisons between the two issues. (The comparisons are elaborated in table 6.1.)

|

The level of political involvement by scientists in the climate change issue is unprecedented in international environmental politics. 5 Since 1985, scientists have been calling for action to stabilize the climate system, which would require as much as a 50 percent equivalent reduction in carbon dioxide emissions (Usher 1989:26). Such sweeping recommendations stand in marked contrast to the virtual silence of scientists on CFC reductions prior to 1987 and their relatively low profile since the Montreal Protocol. If the issue is truly shrouded in scientific uncertainty, as it is popularly believed to be, then the prominence of scientists on the political scene is rather puzzling. This puzzle can be partially clarified by considering that most of the scientific uncertainties revolve around the timing and the degree of anticipated climate change, not around whether major changes occur. A broad consensus exists among scientists that it is a "very, very real problem" and that humanity is "moving the climate into uncharted territory" (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 1990). Consequently, it is not surprising that large numbers of scientists oppose behavior that will induce unprecedented conditions on a global scale.

At least some scientists were encouraged by the Montreal Protocol experience to become more outspoken on policy issues. Because ozone and climatology are both atmospheric problems, there is some overlap in the scientific communities that address them. By the late 1980s, many of the relevant scientists were accustomed to being in the political limelight. After the Montreal Protocol, both environmentalists and scientists focused their attention on the climate problem (Nature 1987a).

Despite the apparent existence of a powerful epistemic community of scientists, environmentalists, and political leaders in favor of regulatory measures, such measures have yet to be adopted. Because of strong objections by the United States, the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) adopted a Climate Change Convention that contains no specific control measures. Nonetheless, the treaty's stated objective is "to prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system" (UNCED 1992). This convention, negotiated in Rio, may serve the same function for climate as the 1985 Vienna Convention did for the ozone issue: it may establish a discursive norm in favor of precautionary action that may eventually be implemented.

All of this is indicative of the limits of discursive practices. The very term discourse is derived from a Latin word meaning "a running to and fro." Discourses do not solve environmental problems - they merely offer alternative interpretive lenses through which problems can be viewed, lenses that lend themselves to certain policy solutions. The climate change problem demonstrates that consensual knowledge does not guarantee concerted international action. Strong opposition from one key state can lead to a perpetual "running to and fro," even if all the running is rationalized on scientific grounds.

Discursive power, particularly that associated with scientific knowledge, is likely to be increasingly important in the future. And, as environmental problems become more serious and more globalized, science can be expected to play an expanded role in institution building. Other developments in the international system are likely to reproduce and reinforce this pattern. National security, traditionally viewed in terms of military power, has become more complicated as the nature of the threats has shifted toward economic and environmental dangers (Nye 1990:179). 6 The simultaneous decrease in the utility of military power as an instrument of foreign policy and the new prominence of nonstate actors has cleared a space for knowledge-based power. 7 In the same way, the declining utility of force and the informational nature of many contemporary international problems promotes greater involvement by nonstate actors, since knowledge, once produced, is accessible to many people. The proliferation of information that has accompanied the postindustrial revolutions in computers and communications technology has been instrumental in this regard.

Many indicators, including the number of scientists and other professionals employed in the service economy, document the shift to an informational as opposed to a resource-based mode of production in the affluent countries. This shift represents a major transformation of the social structure, one that places knowledge at center stage. The new social genre has been referred to variously as "cybernetic" (Bell 1973), "technocratic" (Brzezinski 1968), "programmed" (Touraine 1972), "post-industrial" (Touraine 1972; Bell 1973), "knowledgeable" (Lane 1966), "active" (Etzioni 1968), and "post-modern" (Kavolis 1970, 1972; Bell 1973). Despite their differences, all these thinkers emphasize the centrality of knowledge in the new social order, and most are optimistic about this development. In general, the theorists of postindustrialism devote little analysis to the key theoretical categories of information and knowledge, treating them as monolithic and uncontroversial. Thus, much of that literature is consistent with the aims of the rationality project (Stone 19888).

Nonetheless, there are real signs of a shift toward a postindustrial society, a shift that has important implications for our understandings of power. 8 Undoubtedly, a society's generally accepted view of power is determined by an entire social context. A civilization that reduces the world to a mechanical aggregate of material objects to be exploited for individual gratification is bound to reduce power to its physical dimensions (Skolimowski 1983). Perhaps a postindustrial society, based on modes of information rather than modes of production, would be more likely to grasp power in its cognitive and subjective dimensions. This reconceptualization, implicit in the recent turn toward reflective approaches to world politics, may betoken a more general trend toward the subjectivization of the study and practice of world politics.

James Rosenau offers the first comprehensive effort to explicate a theory of world politics for a postindustrial age. He suggests that "post-international politics" is increasingly bifurcated, with traditional state actors on the one side and a proliferation of nonstate actors, including businesses, social movements, experts, and international organizations, on the other (1990). Not only the actors are changing; so is the nature of power. Rosenau believes that, because "scientific proof" is becoming elevated as a major political tool, "the tendency to contest issues with alternative proofs seems likely to grow as a central feature of world politics" (203). Power in post-international politics, then, would be primarily discursive.

Other analysts concur with Rosenau's observations that postindustrial world politics are distinguished by a "diffusion of power" away from state actors to nonstate actors (Nye 1990:20). The diffusion of power coincides with a shift away from traditional notions of "hard" power to "softer" forms of "co-optive" power. The former entails influencing other states' behavior through either inducements or threats, whereas the latter rests on the attractiveness of one's ideas or on the ability to set the political agenda (31Ð32). Co-optive power ranges from cultural and ideological factors to scientific information.

The prevalence of scientific discourse should not delude us into the common misconception that politics will therefore become more rational and less conflict-ridden, whether through functional cooperation, epistemic communities, or postindustrial technocracy. The modernist faith in science dies hard, however, even for those who foresee turbulence as the dominant mode of the future. Rosenau observes, for instance, that the enormous increase in the supply of information has accentuated the practice of seeking knowledge before making decisions. From this he concludes optimistically that "the 'science of muddling through' may well give way to the science of modeling through" (1990:324). Rosenau discerns within the rise of scientific proof in international politics a nascent "global culture" (421Ð22). The experience in negotiating the ozone regime suggests, however, that inasmuch as scientific discourse permeates political debates, as often as not it serves to articulate or rationalize existing interests and conflicts.

A discursive approach is particularly germane to a social field pervaded by the "mode of information" rather than the "mode of production" (Poster 1984). The commodification of consciousness through representation and "hyperreal simulation," for instance, provides a provocative description of postindustrial dynamics, ranging from advertising to computer modeling (Baudrillard 1975, 1981, 1983). Environmental politics can offer some key nodes for the study of disciplinary power and surveillance. The nations of the earth have fixed their collective disciplinary gaze on the earth itself, resulting in a multitude of new discursive practices.

A discursive approach suggests that the profusion of information may lead to greater confusion as the world becomes a ubiquitous market for discourses. Frederic Jameson's observation may well be correct: "No society has ever been quite so mystified as our own, saturated as it is with messages and information" (1981:60 - 61; quoted in Terdiman 1985:46). The gigantic volume of environmental data generated in the past two decades by a host of monitoring and research programs may at times hinder rather than facilitate the process of environmental management. The process of delegitimation is fueled by the demand for legitimation.

And, as the global warming debates have revealed so starkly, the distribution of knowledge is far from even. The proliferation of information characteristic of postindustrial society is occurring far more rapidly in the North than in the South. About 95 percent of the world's production of chemical knowledge in 1980 was available in only six languages, and two of these, English and Russian, accounted for over 82 percent (Laponce 1987:198; quoted in Rosenau 1990:427 - 28). As one analyst of trends in environmental information argues, "The information-rich will become richer, and the information-poor will not even suspect what they have missed" (Davis 1974:27).

The equation, however, is not so simple: the information-poor are suspicious, and they may compensate for their deficiencies in surprising ways. Most obviously, while scientific knowledge can be an important political resource, it is quite different from standard material resources. Access to knowledge does not necessarily bestow political influence; persuasion is an essential ingredient in the process. Knowledge is only a useful tool when others are convinced of its validity or, more precisely, of the validity of the proponent's interpretations of it. Such cognitive processes are not easily predictable and are shaped by seemingly serendipitous events like the weather or the Antarctic ozone hole. All of this suggests a distinctive power-of-the-weak phenomenon; those without access to informational resources may simply refuse to be persuaded.

A core issue, then, is whether the apparent "scientization of politics" observed by analysts of epistemic communities and advocates of postindustrialism is not really the "politicization of science" (Weingart 1982:73). While "the language of science is becoming a worldview that penetrates politics everywhere" (Haas 1990:46), old cleavages may simply be recloaked in new scientific garb. Epistemic dissension may be as likely an outcome as epistemic cooperation.

In this sense, there are both hopeful signs and causes for concern. Scientific discourse can be employed skillfully to persuade states to adopt precautionary policies jointly. Yet the celebratory mood that has surrounded the Montreal Protocol and its revisions must be tempered with the recognition that it took thirteen years for this "sudden global emergency" (Roan 1989) to be addressed with concrete action. The ozone protocol was too late to prevent the Antarctic ozone hole and probably would not have contained the provisions that it did without the hole. The most recent revisions, adopted in Copenhagen, are likely to be rapidly outstripped by accelerating ozone depletion. Even in this "most likely case" of the global ozone regime, there was no clear path leading from consensual knowledge to international cooperation.

This raises the larger question of the role that scientific knowledge can be expected to play in formulating environmentally responsible policies. Conventional wisdom among environmentalists has been that scientific knowledge communicated to people and political leaders will lead to ecologically sustainable societies: education engenders action. The faith in the power of science, as I have argued, runs deep. There are, however, two arguments - based on two different views of science - against this position. The first is that, because science deals with the world of facts, not values, and because values are ultimately what inform our actions, we cannot expect science to save us. Rather, what is required is a reorientation of fundamental values regarding human relationships with the biosphere, whether through political, ethical, or religious movements (Caldwell 1985). The second argument rejects the premise that science and politics, facts and values, are wholly divorced from one another. In this view, science can promote sustainable policies when it is used as a political tool and framed in ways that enhance environmental preservation, as was the case when a group of knowledge brokers deftly defined the terms of the ozone debates. Paradoxically, the more skeptical view of science acknowledges its real power; the key questions in this view then become how knowledge is framed, by whom, and on behalf of what interests.

On a deeper level, these arguments are not fundamentally inconsistent with one another. In both cases, values are the key to developing environmentally responsible policies. As I argued in the study of the ozone regime, the discourse of precautionary action was not mandated by scientific knowledge but grew out of a particular interpretation of that knowledge. Yet, so long as science serves as a universal legitimator, values alone will not be sufficient to forge international regimes to protect the global environment; the skillful employment of scientific discourse is essential. The political impact of scientific knowledge is determined far more by its incorporation into larger discursive practices than by either its validity or the degree to which it is accepted by scientists. Science, then, is not likely to save us from environmental ruin, persistent political action informed by carefully chosen discursive strategies might.

Note 1: This revival hearkens back to the recurring debate in the social sciences between materialism and idealism. It appears as if the pendulum of international relations theory may now be swinging, after several generations, in the direction of the latter. Back.

Note 2: Economist Charles Kindleberger, a chief proponent of the first viewpoint, ties hegemonic status to an ethical responsibility to lead (1973, 1986). The second version eschews Kindleberger's latent liberalism and is more widely accepted among international relations theorists, particularly those seeking to explain the formation of economic regimes in the postwar period (Krasner 1976; Keohane 1980; Gilpin 1981). Back.

Note 3: I specify that these two categories of beliefs are only separate analytically because, as was argued in chapter 2, in practice they tend to merge. Much of the critical literature on risk analysis develops from this observation. Back.

Note 4: It is ironic that the field of international relations, in which conflict figures so centrally, would take such a sanguine view of the role of science. One possible explanation is the intellectual legacy that sees science as a salvation from politics or at least as providing an objective, value-free basis for political consensus. Or perhaps liberal theorists, wishing to flee the contentious nature of world politics, seek some basis for consensus, some common language. Science, as a universal legitimator, seems to provide that common ground. Back.

Note 5: Over sixteen hundred scientists, including the majority of the living Nobel laureates in the sciences, have signed the "Global Warning," calling upon the world's leaders to cut greenhouse gas emissions and to move away from fossil fuel dependence (Nucleus 1992Ð93). Back.

Note 6: On some of the pitfalls involved in applying the language of national security to environmental problems, see Deudney (1990). Back.

Note 7: On the declining utility of military force, see Rosecrance (1986); Baldwin (1985), and Nye (1990). While the most recent literature draws its cogency from the end of the Cold War, it also extends a school of thought that was influential during the 1970s (see Keohane and Nye 1977). Recent events such as Tien An Men Square and the Persian Gulf War seem to cast doubt on the "declining utility of force" thesis. Yet a deeper analysis reveals the striking extent to which these events, principally because of their direct coverage by the electronic media, were about ideas, persuasion, and the ability to sway world opinion. Back.

Note 8: Whether the shift toward postindustrialism might also entail a shift toward a postmaterialist value structure, as some have argued (Inglehart 1977), remains to be seen. Back.