|

|

|

|

Cosmopolitan Capitalists: Hong Kong and the Chinese Diaspora at the End of the 20th Century, by Gary G. Hamilton (ed.)

3: Chinese Cities: The Difference a Century Makes

G. William Skinner

What difference does a century make? In this chapter I ask this question about China's cities and systems of cities. I pose the question in terms of a century not because a hundred-year span has any intrinsic significance, but simply because my own research career has inadvertently provided a setup. Twenty years ago I completed a study of Chinese cities as of the 1890s, the latest possible date for analyzing them prior to any significant modern transformation. The Treaty of Shimonoseki, which ended the Sino-Japanese War, triggered the onset of urban industrialization in China, so I took 1895 as my year of reference. In 1995 I was engrossed in a project designed to take advantage of excellent disaggregated data that have become available only in the 1990s, and today I'm nearing completion of a regional analysis of contemporary China. So, as it happens, I have something to go on in comparing China's cities today with those of a century ago. Such a comparison can serve to dramatize the magnitude and significance of urban change, while pointing up certain continuities. It can also provide context for an assessment of Hong Kong's changing role in China's urban system.

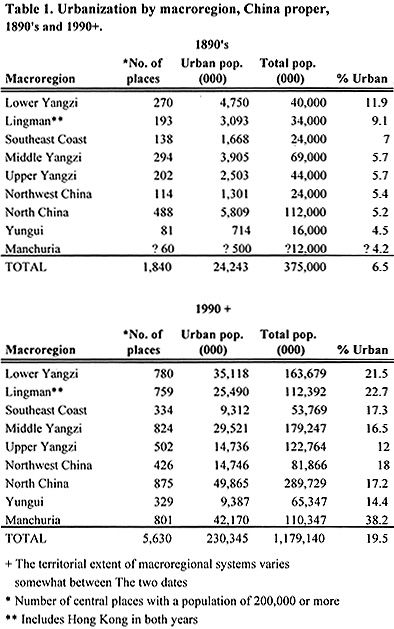

Let's start with the big picture. In the 1890s China's urbanization index was between 6 and 7 percent; as of 1990 it was about 20 percent. The urbanization index is the proportion of the total population residing in urban centers and, as such, is a function of the criteria used in classifying settlements as urban; so let me say that no matter how urban is defined–whether in terms of function, centrality, or population size–the magnitude of the change comes out about the same: The level of urbanization has increased threefold in the course of the last century. It will help us appreciate the significance of that change to look at some absolute figures. Focusing on the total row of Table 1, you will note that during the century, the population of China Proper (that is, excluding the Inner Asian territories) grew from approximately 375 million 1 to over 1.1 billion–almost exactly a threefold

increase. We may note that the total number of cities and towns with a population of 2,000 or more also increased about three times, from 1,840 to 5,630. 2 It follows that the total urban population must have grown about ninefold during the century and that the growth rate has been higher in large cities than in small cities and towns. Note the magnitudes involved. China's urban population was 24 million in the 1890s, and over 230 million in 1990. 3 That's more urbanites than we find in any other country of the world, regardless of urbanization level.

You might well ask how important cities and towns could have been for Chinese society and political economy in the 1890s, when the urban population accounted for less than 7 percent of the total. In fact, as in most agrarian civilizations, the urban hierarchy was all-important in shaping rural life. On the one hand, the entire governmental apparatus was urban, with lines of authority and control emanating from the imperial capital in Beijing, to provincial capitals, and on down to the capitals of prefectures and counties. On the other hand, all cities and towns, not just those that served as administrative capitals, provided economic and other central functions for their hinterlands and, in so doing, differentiated those hinterlands in significant ways. The general economic importance of an urban center in late imperial times was in large part a function of three factors: (1) its role in providing retail goods and services for a surrounding tributary area or hinterland, (2) its position in the structure of distribution channels connecting economic centers, and (3) its place in the transport network. In an analysis of 1890s data that systematically investigated these functions of cities and towns, I found that China's great metropolises were but the highest level of a seven-level hierarchy that extended down to rural market towns (Skinner 1977b). The marketing systems centered on these bottom-level towns, each typically encompassing 15-20 villages, constituted the basic building blocks of the economic hierarchy. Central places at each ascending level served as the nodes of ever more extensive and complex socioeconomic systems. At each level, the town or city at the system's center served to articulate and integrate activity in space and time. Just where a village was situated within this hierarchy of local and regional systems and, in particular, how it was related to the cities and towns at their centers overwhelmingly determined social and economic opportunity, living standards, and quality of life.

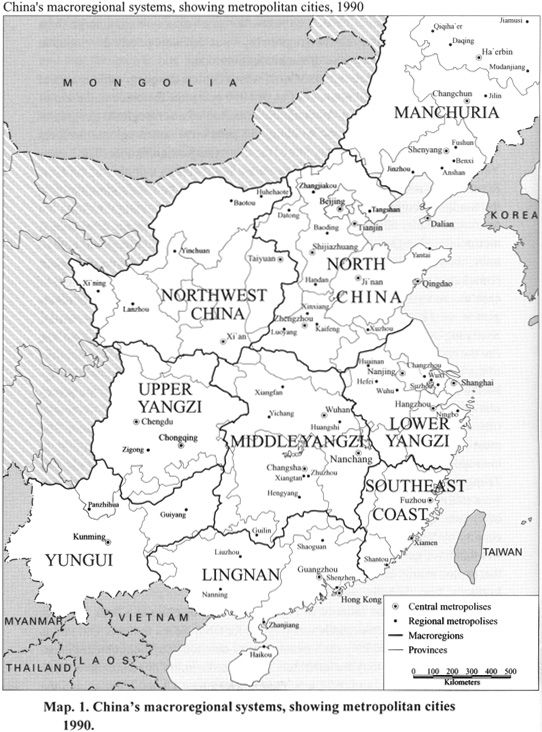

When considering systems of cities, we must recognize that China is on quite a different scale from Japan, Thailand, Iran or France. Throughout the last century, it has been more or less 10 times as populous as these standard-sized countries, and its internal differentiation has been and is correspondingly sharper. By the end of the nineteenth century, Tokyo, Bangkok, Teheran, and Paris each served as the central metropolis of a single, integrated urban hierarchy. The same could not be said of China. Based on my analysis, in the 1890s there were seven distinct regional urban systems, plus two emergent systems in the process of cohering into a hierarchical urban system. Rather more surprising–and this is the most significant of the continuities I'll touch on here–the same nine systems emerge from my analysis of 1990 data. The two regional systems that were poorly developed in the 1890s have fully integrated urban hierarchies today.

We may pin the discussion to Map 1, which depicts the geographic extent of these nine macroregional economies as of 1990 and plots the cities at the top of each regional urban system. A detailed comparison of macroregional geography reveals many shifts of boundaries along the peripheral macroregional frontiers between 1890 and 1990, but only one of these is of major significance. The Lower Yangzi region has expanded both to the north, incorporating a portion of the Huai River valley, and to the south, capturing, as it were, the Ou-Ling subregion from the Southeast coast. This territorial expansion of the Lower Yangzi reflects the continued vitality of its regional economy and the growing centrality of its central metropolis, Shanghai. Despite these shifts in the limits of macroregional economies, their core areas have changed little since the 1890s. And there has been remarkable continuity in the central metropolises integrating the urban system of each macroregion. Of the two macroregional economies that were merely emergent in the 1890s, Manchuria and Yungui, the present-day central metropolises, Shenyang and Kunming respectively, were already dominant a century earlier. For the rest, then and now, we find Chengdu and Chongqing the twin metropolises of the Upper Yangzi, Wuhan the central metropolis of the Middle Yangzi, Shanghai the central metropolis of the Lower Yangzi, Fuzhou the metropolis of the Southeast coast macroregion, Xi'an and Taiyuan the twin metropolises of Northwest China, and Beijing and Tianjin the twin central metropolises of North China. The most important exceptions to this overall continuity are four cities that rose to metropolitan rank in the course of the century. Two of these, Shijiazhuang and Zhengzhou in North China, are sited at the junction of major north-south and east-west railroads that were completed shortly after the turn of the century, and the other two, Qingdao and Hong Kong, are outports established in the nineteenth century by Western metropolitan powers. Another major category of urban centers that have moved up the hierarchy during the past century are industrial cities that exploit nearby mineral resources, for example, Anshan in Manchuria, Tangshan in North China, and Zigong in the Upper Yangzi.

In emphasizing the salience of regional systems of cities in China, I do not mean to deny their interdependence; they are far from closed systems. But just as France, Germany, and Italy each boasts a semi-autonomous, hierarchical system of cities, even though they are intricately interrelated within a more inclusive Western European system, so the Lower Yangzi, Northwest China, Yungui, and the other regional urban systems of China must be recognized as semi-autonomous despite their partial integration into a national Chinese economy. In the sense that Paris is the metropolis of France, Shanghai is the metropolis of the Lower Yangzi. But at the next level up, no city or pair of cities predominates. China's urban system, like Europe's, is decentralized.

It is, of course, true that interregional trade has grown enormously during the past century, facilitated by the expansion of mechanized transport, and it might be thought that this would inevitably strengthen the national economy at the expense of regional economies. But that argument overlooks the fact that transport modernization and trade growth have proceeded within as well as between regions. Macroregional systems of cities are far more tightly integrated today than they were a century ago, and in at least some macroregions the internal transport net has been greatly expanded and upgraded, whereas interregional routes, despite mechanization and upgrading, have not been appreciably intensified. That we find remarkable continuity and only very gradual change in the structure of China's urban systems attests the inertia induced by such factors as the largely unchanged structure of navigable waterways, sunk costs in cities and overland transport routes, the pervasive constraints of cost-distance in relation to topography, and the inexorable logic of increasing returns. In short, path-dependent development and historical contingency.

A closer look at Table 1 shows that the level of urbanization varied sharply from one macroregion to another–in 1990 as in the 1890s. The macroregions are listed in order of urbanization in the 1890s. Above all, the order reflects position with respect to the major waterborne trade routes. The Lower Yangzi, the most urbanized region, encompasses the mouth of the Yangzi, i.e., where the major internal waterway links to coastal trade routes. Next most urbanized were the coastal regions to the south, and after them the Yangzi regions farther upstream. By far the most dramatic change in urban systems during the past century took place in Manchuria. From 1668 until the last decades of the nineteenth century, the Manchu court banned the migration of Chinese peasants into the region. But this exclusion policy was eventually abandoned in the face of foreign threat and population pressure in North China, and by 1904 the entire region was open to peasant in-migration (Lee 1970). Russian and Japanese rivalry stimulated precocious development of an extensive rail network, which in turn facilitated the influx of land-hungry peasants from the North China macroregion. Then, early in the 1930s, the Japanese occupied the region and converted it into an industrial base. The PRC regime systematically built on this legacy. So it was that in the course of a century flat, Manchuria went from the weakest of China's macroregional economies with an urbanization index of under 5 percent to the country's most urbanized economy. More generally, it will be noted in Table 1 that differential rates of change during the past century have had the effect of reducing urbanization differences among the various macroregional systems. After Manchuria, the three regions that were least urbanized in the 1890s–Yungui, and North and Northwest China–saw higher than average levels of urban growth during the past century, whereas the most urbanized of the macroregions in the 1890s, the Lower Yangzi, exhibited a relatively low rate of urban growth during the century. 4

Let us pause here to take a closer look at Lingnan's urban system at the close of the nineteenth century, with special attention to the role of Hong Kong. Then as now, the inner core of the Lingnan macroregion was very nearly coterminous with the Pearl River delta. The delta was, of course, dominated by Guangzhou (Canton), the central metropolis of the entire macroregion, but at the next level down it also supported two regional cities: Foshan and Jiangmen. Hong Kong's population, over 250,000 in 1898, placed it on a par with these two delta cities, but its central functions were anomalous: more limited that those of a regional city in certain ways, more extensive in others. On the one hand, Hong Kong lacked a "proper" hinterland, that is, an extensive dependent territory for which it provided the full range of urban functions. Foshan and Jiangmen were at once cultural and economic centers for their respective subregions, funneling goods, services, and credit into local distribution channels and housing religious, cultural, and welfare institutions that served, inspired, or interfaced with local systems. In these respects, Hong Kong's centrality did not extend beyond the New Territories, which it annexed in 1899. On the other hand, with respect to shipping, trade, and migration, Hong Kong played a role that was critical for the entire macroregional economy. As of the 1890s, Hong Kong had already become the major transshipment center for most of Lingnan (Endacott 1973; M. Chan 1995). To be sure, Guangzhou continued to dominate inland transport and trade within the macroregion, serving as the central collection point for exports and the distribution center for imports. But most of these imports and exports were transshipped in Hong Kong, which, in addition to its superior harbor facilities, offered banking, accounting, and insurance services geared to international trade. Hong Kong was also the usual port of embarkation for emigrants originating in central Lingnan (Endacott 1973). Often recruited by and through agents in Guangzhou, prospective emigrants usually proceeded by riverboat to Hong Kong, where over a hundred boarding houses served the "coolie traffic." Around the turn of the century, Hong Kong shipped out some 100,000 emigrants every year, almost entirely Cantonese and Lingnan Hakkas, to destinations in Southeast Asia, the Americas, and Australia/New Zealand (M. Chan 1975: 37). As of the 1890s, then, Hong Kong had usurped some of Guangzhou's metropolitan functions and served as Lingnan's major link to the world system.

To this point, I have emphasized continuities in the regionalization of China's urban system and in the dominant position of its major cities. But when we shift our focus from systems of cities to the cities themselves, we find that the twentieth century has brought about dramatic transformations. In their very physical appearance, Chinese cities today bear little resemblance to those of a century ago. We are fortunate to have access to a splendid corpus of photographs from the late nineteenth century that document the appearance of Chinese cities and their residents (e.g., Thomson 1982; Boerschmann 1982; Beers 1978). The architecture, especially the roof lines, the attire of the people on the streets, the iconography of arches and shopsigns–indeed, virtually every manifestation of culture that can be gleaned from such visual records–are unmistakably Chinese. And the absence of telephone poles, electric transmission wires, streetcars, buses, or even bicycles in these photographs of street scenes mark these cities as unmistakably pre-modern. Sad to say, the modernization of Chinese cities has entailed systematic de-sinification. Unreconstructed pockets are still to be found in some cities, but it is precisely these recognizably Chinese neighborhoods that lack sewers and other modern amenities. For the most part, the advent of mechanized transport–streetcars and buses and more recently motorbikes and automobiles–and a century of urban reconstruction and expansion have yielded cityscapes that are sprawling, rectangularly drab, and virtually culture free. In late imperial times, all cities that served as capitals, over 1,500 of them, were walled, and boasted both a bell tower and a drum tower near the center of the city. The state cult prescribed particular altars for sacrificial rites outside the walls and Confucian and military temples within. With few exceptions, these glorious artifacts of Chinese civilization are gone, if not torn down by mindless modernizers then destroyed by Maoist radicals in their zeal to discard the old, combat religious superstition, and free the socialist present from its feudal past.

Despite the antiquarian bias just revealed, I hold no particular belief for late-imperial administrative arrangements as they affected cities or for the prevailing modes of governance. These arrangements were in fact rather anomalous. In general, cities were not administered or governed separately from the county to which each belonged. Most–but not all–important cities were capitals in the sense that the magistrate's yamen was situated within the walled city, but the magistrate's responsibilities were not formally differentiated between city and countryside. In some of the highest-order capitals, the local administrative arrangement was even odder. Such metropolises as Beijing, Xi'an, Chengdu, Changsha, Nanchang, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Fuzhou, and Guangzhou each served as the capital of two counties. In these cases, the county boundary ran through the city, and the yamen of each county was located in the appropriate sector (Skinner 1977b). To be sure, the city as a whole was under the jurisdiction of the prefectural yamen, but once again only as an undifferentiated part of a much larger, primarily rural administrative unit. Quite apart from bureaucratic arrangements, in most cities of any appreciable size the population had organized itself into neighborhoods, normally defined in terms of streets rather than blocks, and these neighborhood associations, usually in the form of religious hui, took responsibility not only for the ritual purity of the area but also for its general order, harmony, and cleanliness (Schipper 1977; Skinner 1977c). In addition, major urban temples often became the foci of territorial units uniting several neighborhoods. By the late nineteenth century, many urban services were provided by non-governmental corporate groups financed through assessments and dues or the income from corporate property. The trend was toward cooperation, if not federation, among guilds, native-place associations, and/or gentry-dominated boards to provide a number of citywide services, including firefighting, policing, garbage collection, and charity (Rowe 1984; Elvin 1974; Skinner 1977c).

During the first half of the twentieth century, these ad hoc arrangements were superseded in many cities by the creation of true municipalities: formal administrative units limited to the city and detached from the surrounding county. This administrative practice was extended to lower-order cities by the Communist regime, and there are now some 500 municipalities Chinawide, though, to the confusion of not a few urban analysts, many county-level municipalities differ from counties only in name. In any case, the urban population today is formally organized under neighborhood committees, which, in the case of larger cities, are subordinate to government offices at the urban district or ward level. The rural administrative hierarchy of county-township-village is thus paralleled by an urban hierarchy of municipality-ward-urban neighborhood. State control is exerted not only via this territorial hierarchy but also through the danwei, or work unit, to which most urbanites are formally attached.

How do urban populations today differ from those of the 1890s? The most significant change has to do with gender composition or sex ratio. If one scrutinizes century-old photographs of Chinese street scenes, it becomes apparent that virtually all of the passersby were men. This reflects not only the fact that respectable women did not venture into the streets but also the strongly skewed sex ratio of rural-to-urban migration. In societies with patrilineal joint family systems such as that of traditional China, young women were kept close to home (if not at home) under the watchful eyes of parents before marriage and of parents-in-law after marriage. Only men were sufficiently mobile to take advantage of economic opportunities away from home. Those opportunities were concentrated in cities, and the sojourning strategies that were a characteristic feature of the premodern Chinese economy were largely limited to men. Women played virtually no role in the larger political economy prior to the Revolution. Urban merchants were almost exclusively male, and the bureaucratic state apparatus, wholly urban as noted earlier, was literally manned, that is, staffed entirely by men. Even clerical workers in the yamens were men, as were the jail wardens guarding female prisoners. As a consequence, prosperous cities that attracted large numbers of sojourners were very disproportionately male; city-wide sex ratios of over 200 were not uncommon.

In fact, to characterize family and gender patterns in late-nineteenth-century Chinese cities adequately, one must draw a critical distinction within the urban ecology. Most cities were characterized by two nuclei: one the center of merchant activity, the other the center of gentry and official activity (Skinner 1977c). The business district was dominated by shop-houses in which the salesrooms of stores and the workrooms of craft shops doubled as dining rooms and sleeping rooms for the largely male employees. Quarters were cramped because of high land values, the normal desire of businessmen to keep non-essential overhead down, and the frugality of sojourners. The sex ratio was sharply skewed because of the high proportion of sojourners who had left their families behind in their native places and the large number of unmarried apprentices. Men with families in the business districts were mostly shopowners, and their wives cooked meals for the entire workforce; their families were usually simple conjugal units: the married couple and their children. Apart from shopkeepers' wives, the only other women in the business districts were actresses, entertainers, and prostitutes. Certainly some of the men were functionally literate, but virtually all women in the business districts were illiterate. The location of the business nucleus appears to have been determined more by the merchants' transport costs than by convenience of access for consumers, and it was typically displaced from the geographic center of the walled city toward (or up to or even beyond) the gate or gates affording direct access to the major interurban transport route.

Not surprisingly, residents of the urban gentry tended to cluster near the official institutions of greatest interest to them. Academies, bookstores, stationery shops, and used-book stands favored locations near the Confucian school-temple and examination hall, and in general the gentry nucleus of the city tended to be on the school-temple side of the yamen. The gentry district was characterized by a high proportion of residences with spacious compounds, by relatively large and complex families containing more than one conjugal unit, and by a female population swelled by the concubines and maidservants of gentry households. Sex ratios, though far less extreme than in the business nucleus, were still unbalanced because of the concentration in these districts of sojourning male students and, in high-level capitals, of expectant officials. Sex ratios in gentry-dominated urban wards were typically 150:175, as against 225:300 in the business districts. In sharp contrast to the business districts, the men in gentry-dominated wards were normally classically educated and some of their wives and daughters were literate.

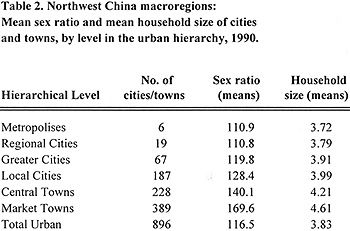

Changes in the gender system over the past century have been truly revolutionary in the cities, with major progress in the direction of greater equality occurring during the Maoist era. Even before the 1911 Revolution, urbanites were leading the way in establishing girls' schools and ending footbinding. The development of urban industry after 1895, especially the expansion of textile mills, meant that women could seek urban employment not only as sex workers and domestic servants but also as factory workers. The modest advances in female education and urban employment opportunities for women during the Republican period were followed during the Maoist era by dramatic educational advances and all-out efforts to bring women into the extra-domestic labor force. The Maoist programs to foster gender equality were particularly successful in the cities, and their legacy has not been appreciably undone by the more gender-differentiating policies of the Reform era. Today, the gender balance in cities is much less skewed than it was in the 1890s. The mean sex ratio of high-order cities as of 1990 varies from 103 in Manchuria and 106 in the Lower Yangzi to 112 and 113 in the Upper Yangzi and Yungui, respectively. As these extremes suggest, the sex ratio of cities is inversely related to the regional level of urbanization–relatively balanced in highly urbanized macroregions, relatively male-heavy in regions with low levels of urbanization. In addition, the sex ratio of city populations tends to increase as one moves down the urban hierarchy. The progression happens to be perfectly regular in the Northwest China macroregion, as shown in Table 2, but a similar albeit less monotonic trend obtains everywhere. In sum, the proportion of females in urban populations today is highest in the metropolitan cities of the most urbanized macroregions, with the proportion of females declining with regional urbanization and down the urban hierarchy.

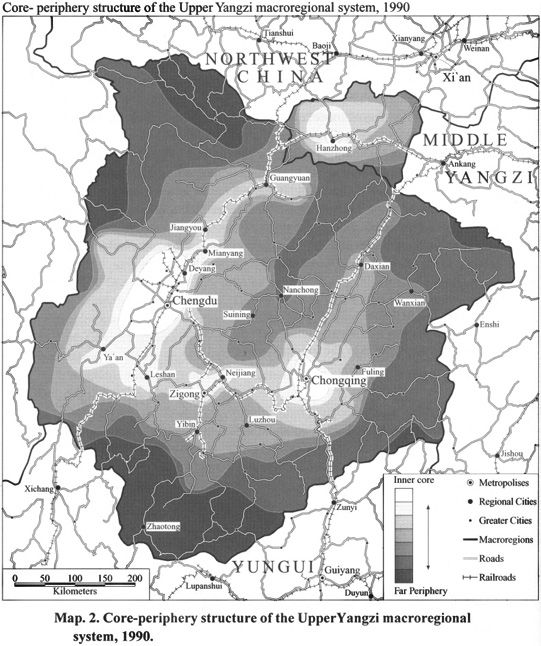

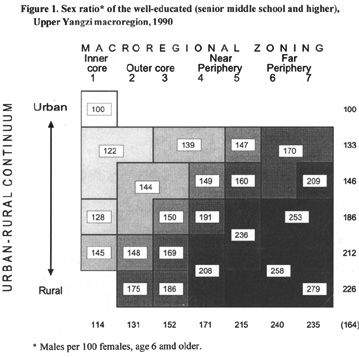

That gender equality is more closely approximated in cities than in the countryside is apparent across a wide range of variables as of 1990. For instance, in the Upper Yangzi (my main case in point in the remainder of this paper), 74.5 percent of urban women over age 15 have been educated to the junior middle-school level, as against only 24.6 percent of rural women. Dichotomous contrasts of this kind, however, miss out on significant differentiation within the urban hierarchy. In fact, women's educational attainment and the opportunities for female employment both vary by level in the urban hierarchy. The closest approach to parity with men is seen in metropolises, with female disadvantage increasing steadily down the urban hierarchy and with distance away from the regional metropolis. Let me illustrate this point with data for the Upper Yangzi macroregion in 1990. Figure 1 displays the sex ratio by position in the internal structure of the macroregion of those educated to the level of senior middle school or higher. In this chart, counties are arrayed in rows according to a fancy urbanization index and in columns according to their zone in the core-periphery structure of the macroregion. 5 In comprehending the latter, it will help to refer to Map 2, which delineates the seven zones of the Upper Yangzi's core-periphery structure. The overall argument, borne out by the data in every case, is that the macroregional economy is internally differentiated such that the lowland areas near the metropolis are most "advanced" or "developed" and "modern," with a steady gradation through regional space to the mountainous and rural far periphery, where villages are relatively backward and underdeveloped and distinctly less modern in their sociocultural attributes. As noted earlier, the Upper-Yangzi boasts two metropolises, Chengdu and Chongqing, and it will be noted that each is surrounded by an inner core zone. Zones of the core-periphery system appear as concentric circles around the metropolises. At the level of the outer core (zone 3), the two inner cores are joined to form a horseshoe-shaped regional core. The finger of the periphery (zone 6) jutting from the northern rim southwestward toward the geographic center is roughly equidistant from the two metropolises, at the rim of their respective maximal hinterlands. The most peripheral areas (zone 7) are remote from either metropolis at the rim of the macroregional economy. One way to think of the core-periphery structure, then, is in terms of effective distance from the metropolis, metropolitan influence being greatest in the inner core and weakest in the far periphery.

Turning back to Figure 1, it is apparent that gender differentials in educational attainment are strongly shaped by position in relation to the urban hierarchy. In rural counties at the far periphery of the macroregion (the lower-right cell), that is, in counties most remote from urban influence, whether from the metropolis or from lower-order cities, the sex ratio of the well educated is sharply skewed: for every 100 women with a senior middle-school education there are 279 men. As one moves diagonally across the chart toward the upper left, the female disadvantage grows steadily smaller, with parity achieved only in the upper-left cell, in the two metropolitan cities. The units containing regional cities, (urban centers at the level just below metropolises), are positioned in the second row of the chart, where it can be seen that the female disadvantage increases with distance from the metropolises, the sex ratio of those with senior middle-school education increasing from 122 in the inner core to 170 in the far periphery.

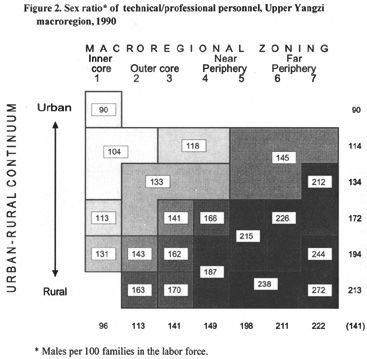

Figure 2 displays in the same matrix the sex ratio of technical and professional personnel (whether in government agencies, state-owned industry, collective enterprises, or the private sector). The general order of magnitude and the patterning of sex ratios within this high-status occupational category closely parallel those for high educational attainment. Sex ratios for other occupations not shown here confirm that gender discrimination within the labor force is at a minimum in metropolitan cities, increasing steadily down the urban hierarchy and out from urban centers into their rural peripheries.

I have not yet analyzed the data on family structure available in the 1990 census returns, so I limit myself here to some very general remarks on family change. Urban youth today have a much greater say in their choice of spouse than had been the case in the 1890s, and the age at marriage is considerably later for both sexes (Whyte 1993). (I am able to show from 1990 census data that, on average, age at marriage is later in cities than in the countryside and that mean age at marriage declines as one descends the urban hierarchy.) The sharp class differentials in family structure that obtained in the 1890s (as between the literati and tradesmen) have largely disappeared. The closest approximation to the traditional joint family system in metropolitan cities today is found among officials and high-level Party cadres (Unger 1993). However, the proportion of stem families is probably no smaller today than a century ago. For most of the big-city population, housing is so restricted that even if desired, it is usually unfeasible for more than one married son to share an apartment with his parents. A not uncommon co-residential sequence amounts to what might be called a hiving-off stem family system. A daughter-in-law is brought in for the eldest son, with the couple occupying a loft or a second bedroom if there is one. When the second son is married, the older brother's conjugal unit hives off to establish a separate household. Ideally the younger or youngest son and his wife remain in the stem family arrangement, caring for the senior couple as they age. Recent social surveys suggest that separate residence of a conjugal family need not imply independence (Davis 1993). A married son may regularly drop off his children at his parents' apartment for care during the working day, and his wife might deliver cooked dishes. Cash and gifts may flow either way according to income and need. A century ago, urban sojourners typically returned to their native places on retirement, while the elderly in urban literati families relied on their married sons. Today, the urban elderly are for the most part pensioned and hence less reliant on married sons for support in old age. Nonetheless, retirement homes are rare, and the great majority of the dependent elderly live with a married child (Ikels 1993). Yet, urban households on average are much smaller today than in the 1890s. The mean size of households in metropolises throughout China ranged (in 1990) from 3.3 in Shanghai and Tianjin to 3.9 in Taiyuan and Nanchang. In all regional systems, mean household size increases as one descends the urban hierarchy; in general, lower-order cities and towns are characterized by housing markets that are less tight, offspring sets that are somewhat larger, and family structures that are more complex. The data shown in Table 2 for Northwest China are typical.

Having described a few of the main social characteristics of China's urban hierarchy, I can now compare how Hong Kong fits into this system of cities. In matters of family, gender, and education, Hong Kong is a bit distinctive, but in most respects it falls within the range exhibited by mainland metropolises. In Hong Kong, it is among the high-echelon business elite (rather than high-level cadres) that we find the closest approximation of the traditional joint family system, and, since a significantly smaller proportion of the elderly are pensioned than in mainland cities, we also observe a somewhat higher incidence of intact stem families. Nonetheless, in terms of averages, household size in Hong Kong (3.4) falls near the low end of the range for Chinese metropolises and contrasts with Guangzhou (mean household size 3.9) and other cities in Lingnan, where urban as well as rural households are on average larger and more complex than in any other Chinese macroregion. With respect to educational attainment, too, it is instructive to compare Hong Kong with its twin metropolis Guangzhou 6 Of the population age 15 and older, 17.9 percent have received some higher (post-secondary) education in Hong Kong, as against 13.1 percent in Guangzhou; at the same time, illiteracy rates are also higher in Hong Kong: 12.9 as against 6.9 percent. This is precisely the contrast one might expect between the two systems: greater investment in higher education and sharper class differentials in capitalist Hong Kong vs. a higher floor and lower ceiling in "socialist" Guangzhou. A more surprising finding, given the Maoist emphasis on gender equality in education, is that Hong Kong's educational system is less sexist than Guangzhou's: females constitute 79 percent of all illiterates in Guangzhou but "only" 72 percent in Hong Kong; more significantly, among those with any higher education the ratio of males to females is 2.02 in Guangzhou as against only 1.28 in Hong Kong.

Let me turn, finally, to the demography of urban populations. In the case of Chinese cities, the century in question encompassed the entire demographic transition from very high mortality and moderately high marital fertility in the 1890s to low mortality and below-replacement fertility in the 1990s. The demographic transition in China has been far more dramatic for the urban than for the rural population.

We may begin with mortality. As in all pre-modern agrarian societies, it was high, but the point to be stressed here is that it was generally higher in cities than in rural areas; specifically, that mortality was highest in inner-core metropolises, declining down the urban hierarchy and through the zones of the core-periphery structure to the far periphery. I offer three reasons for expecting mortality to be highest in large cities in the inner cores of regional systems and lowest in their rural far peripheries. The first is a direct function of occupant density. In densely populated cities, interpersonal contact was frequent and living conditions were crowded. Extensive contact guaranteed a higher level of exposure to airborne pathogens, while crowding facilitated the spread of water-and filth-borne pathogens. The second reason follows from the fact that regional systems took shape within drainage basins and, apart from Yungui, had lowland, riverine cores. The risk of infection from polluted water increased as one moved from uplands to the plain. The danger of water-borne disease was especially great in spring, when rivers tended to flood and drive surface water into wells. As noted earlier, with the exception of Kunming, the major Chinese metropolises were sited in the riverine lowlands of drainage basins. This factor interacts with occupance density in that sewage disposal was a particular problem in cities. The third reason follows from the fact that migration flows were generally from less to more urban settlements and from peripheral locales toward the core. More often than not, the migrants attracted to inner-core cities came carrying a fresh supply of new pathogens and had little resistance to those already present.

I have not documented in any detail the following hypothesis concerning the mortality transition, but I believe some version of this story will fit the Chinese case. The biomedical revolution provided the knowledge to eradicate or control most of the diseases that kept mortality high in premodern times. The practical techniques of preventive medicine (such as inoculation, pasteurization, sewage disposal, insect control, and measures to minimize food contamination and purify the water supply) together with the development of a modern system for health-care delivery made possible a dramatic lowering of mortality. But virtually every one of these medical innovations was introduced in metropolises, spreading only gradually to lower-order cities and surrounding rural areas. The development of a network of hospitals and clinics and of medical schools largely recapitulated the urban hierarchy, as did the distribution of modern doctors and modern pharmacies. Effective health-care delivery to villages was slow in coming, especially to those remote from cities and poorly served by the transport net. In short, we may posit with some confidence that benefits of the biomedical revolution diffused within a regional system down the urban hierarchy and, at each level, out from the urban center into the rural hinterland. The first localities to see a drop in mortality were inner-core cities, where mortality had been the highest; the last localities to benefit were remote villages in the far periphery, the healthiest parts of the realm in the 1890s. One can imagine a magic moment in the diffusion process, perhaps in the 1950s, when, with mortality in the urbanized inner core lowered to levels traditionally enjoyed in a far periphery as yet untouched by biomedicine, mortality levels would be uniform through the regional system. However, as the potential of biomedicine came to be more fully realized in the urbanized inner core at a time when it had barely penetrated the rural far periphery, the balance quickly shifted in favor of the former. At that juncture, although mortality in the far periphery might be no higher than in premodern times, in relative terms the patterning within the internal structure of the regional system had been reversed. The very localities that once enjoyed the highest life expectancies were now burdened with the lowest. And it was precisely in inner-core metropolises that the mortality transition was most dramatic, with life expectancy at birth increasing from around 30 years in the 1890s to over 70 in 1990.

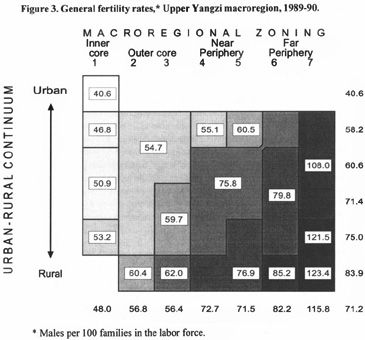

The fertility transition story is both less conjectural and more simply told. Available evidence suggests that at the end of the nineteenth century and, indeed, on through the Republican period, marital fertility was somewhat lower in cities than in the countryside. Be that as it may, it is clear that modern fertility control in marriage first appeared in China among the better educated strata in the major metropolises (Lavely and Freedman 1990). Fertility decline was already under way in the higher reaches of the urban hierarchy prior to the start, in 1970, of the wan-xi-shao program, which promoted delayed marriage, wider spacing between children, and fewer births overall. When the one-child policy was introduced in 1979, most families in inner-core metropolises were motivated to limit the number of offspring, and in any case enforcement of the policy was much stricter and more effective in tightly organized municipalities than in towns and a fortiori in rural villages. Figure 3 displays general fertility rates for the Upper Yangzi in the matrix already introduced. The particular fertility measure used is the number of births per 1,000 women age 15-44, and as you can see it varies sharply across the matrix, being lowest in Chengdu and Chongqing, the region's metropolises (in the upper-left cell), and increasing steadily down the urban hierarchy and through the zones from the inner core to the far periphery. A more detailed analysis of parity progression ratios shows that in the metropolises of Chengdu and Chongqing combined, the proportion of women with one child who go on to have a second fell below 10 percent in 1982 and has been below 5 percent since 1987. This level of fertility is lower than that recorded for cities anywhere in the world outside China.

Similar to the previous comparisons, Hong Kong's demographic trends are in line with those of other metropolitan regions in China. It is especially interesting in this regard that fertility levels in contemporary Hong Kong are no higher than in mainland cities where the one-child family policy has been strictly enforced. Indeed, the general fertility rate in Hong Kong is a bit lower than in Guangzhou: 43 vs. 48. 7

To summarize: It is precisely the cities in China that have seen the most dramatic changes during the past century–in the family system, in the occupational structure, in education, in the demographic regime, and in gender relations, which crosscuts all the others. In all these respects, the magnitude of the transformation during the past century has been greatest in the metropolitan cities at the apex of regional hierarchies, declining down through the urban hierarchy and with distance from the metropolis. These dimensions–level in the urban hierarchy and position in the macroregional core-periphery structure–are critical for analyzing differentiation among cities, in the 1990s as in the 1890s. And I have argued here that the very extent of social transformation experienced by particular cities is a function of the same spatial logic. The most significant continuity during the past century is to be seen in the continued salience of China's regional systems of cities. The cities themselves are virtually unrecognizable across the century, and their populations, too, have been fundamentally transformed. It is the spatially grounded hierarchical structure of urban systems that has endured.

Let me close with a coda on Hong Kong's changing role in Lingnan's urban system. During the first four decades of the twentieth century, Hong Kong experienced rapid population growth through in-migration from Lingnan and almost equally dramatic development of its entrepôt economy. On the eve of the Sino-Japanese War, Hong Kong's pretensions to metropolitan status had largely been realized, and it was more closely integrated into Lingnan's economy than ever before. Events of the next 15 years, however, fostered the industrialization of Hong Kong's economy and led to its eventual isolation from the mainland (M. Chan 1995; Endacott 1973; Liu 1997). Hong Kong's entrepôt trade was badly hurt by the Japanese occupation (1941-45), the subsequent civil war in China (1946-49), and the ban on trade with China imposed by the colonial government (at American instigation) after the outbreak of the Korean War in 1953. Hong Kong's industrialization benefited twice from the influx of Chinese businessmen fleeing Shanghai and Guangzhou, bringing their capital and technology with them: first in the late 1930s, when these mainland cities were conquered by the Japanese, and second a decade later when they were occupied by the People's Liberation Army. Its labor pool was also greatly augmented by the flood of refugees from the Delta during the period of 1948-56. By the late 1950s, Hong Kong's transformation from entrepôt port to industrial center was complete. Hong Kong manufactures, increasingly high-technology products after 1970, were exported not to China but to Southeast Asia and the West. Hong Kong's links with the mainland were greatly attenuated throughout the Maoist era of self-reliance, when Guangzhou was indisputably the sole metropolis of Lingnan's stagnant macroregional economy.

However, the onset of Reform in 1978 precipitated a dramatic restructuring, and Hong Kong's reintegration with the Lingnan economy has proceeded at astonishing speed. Hong Kong industrialists began moving their production north to the Delta in 1980, and today 80 percent of Hong Kong's manufacturing is done on the mainland, most of it in the core areas of Lingnan. Hong Kong also quickly regained its stature as entrepôt. As of 1988, the entrepôt trade surpassed that of locally made products in both volume and value, and by 1994 it accounted for over 80 percent of total exports (Liu 1997). Today, Hong Kong and Guangzhou are twin metropolises of Lingnan, their respective strengths largely complementary. If anything, because of its technological edge and international orientation, not to mention its superiority in shipping, banking, and insurance, Hong Kong is likely to prove the dominant metropolis. In contrast with a century ago, Hong Kong now provides regional-city-level urban functions for a hinterland that incorporates the very areas from which its population largely originated. And in even sharper contrast with a century ago, Hong Kong is today the cultural center of all Lingnan.

Notes

Note 1: Estimates of China's population during the second half of the nineteenth century are based on an official series of provincial statistics for 1850. Recent scholarship has shown that the official 1850 figures for many provinces systematically overstate the actual population (Skinner 1987). The total cited here for China Proper represents a province-by-province downward revision of the 394 million estimated for 1893 in my earlier study of regional urbanization (Skinner 1977a).Back.

Note 2: The figure for the 1890s given here differs from that in Skinner 1977a because of the inclusion of Manchuria. The count of central places in both years undoubtedly misses out on a number of towns in the 2,000-4,000 range.Back.

Note 3: The estimated urban population of 230 million is smaller than that given by other analysts on the basis of 1990 census data. My figure is based on the actual count of urban residents in each city and town (some 12,000 central places in all of China), whereas other China-wide estimates are based on the population of territorial units (municipalities and townships) that often include extensive rural areas. One of the more careful and conservative of the estimates based on data for administrative units (K. W. Chan 1994: 153) suggests an urban population of 313 million. Of the extensive "floating" population in the urbanized cores of China's macroregional economies, only a small proportion represent a net increase in the aggregate urban population (K. W. Chan 1994: 46), and of these many were counted by the census. Extending the estimate to include "floaters" missed by the census would probably add 5-8 million to the total urban population of China proper as of 1990, yielding an urbanization index of 20.2.Back.

Note 4: In fact, this cross-time comparison is biased by an expansion in the territorial extent of the Lower Yangzi macroregion during the intervening century. Since the incorporated areas on the northern and southern peripheries are relatively underurbanized, the percentage of urbanization in 1990 is lower than it would be if calculated for the smaller territory of the 1890s macroregion.Back.

Note 5: For a brief explication of the methodology, albeit applied to 1982 rather than 1990 data, see Skinner (1994).Back.

Note 6: The Hong Kong data in this paragraph, taken from Hong Kong 1991 Population Census Main Report, are for the entire colony, including the small rural population of the New Territories. To enhance comparability, the data presented for Guangzhou, taken from my computerized datafile for 1990, were applied to the municipality, which includes periurban villages, rather than to the central city per se.Back.

Note 7: The general fertility rate is the number of births in a given year divided by the number of women of childbearing age. This is usually taken to mean women 15-44, but the rate for Hong Kong as given in the 1991 census report was calculated for women 15-49. The figure given for Guangzhou is a recalculation with the same denominator.Back.

References

Beers, Burton F. 1978. China in Old Photographs, 1860-1910. New York: Scribner.

Boerschmann, Ernst. 1982. Old China in Historic Photographs. New York: Dover.

Chan Kam Wing. 1994. Cities with Invisible Walls: Reinterpreting Urbanization in Post-1949 China. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Chan, Ming K. 1995. "All in the Family: The Hong Kong-Guangdong Link in Historical Perspective." in The Hong Kong-Guangdong Link: Partnership in Flux, edited by Reginald Yin-Wang Kwok and Alvin Y. So, pp. 31-63. Armonk, N.Y.: M. E. Sharpe.

Davis, Deborah. 1993. "Urban Households: Supplicants to a Socialist State," in Chinese Families in the Post-Mao Era, edited by Deborah Davis and Stevan Harrell, pp. 50-76. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Elvin, Mark. 1974. "The Administration of Shanghai, 1905-1914," in The Chinese City between Two Worlds, edited by Mark Elvin and G. William Skinner, pp. 239-262. Stanford, Cali.: Stanford University Press.

Endacott, G. B. 1973. A History of Hong Kong Rev. ed. London: Oxford University Press.

Hong Kong Census Planning Section. 1993. Hong Kong 1991 Population Census: Main Report. Hong Kong: Census and Statistics Department.

Ikels, Charlotte. 1993. "Settling Accounts: The Intergenerational Contract in an Age of Reform," in Chinese Families in the Post-Mao Era, edited by Deborah Davis and Stevan Harrell, pp.307-333. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lavely, William, and Ronald Freedman. 1990. "The Origins of the Chinese Fertility Decline," Demography 27: 357-367.

Lee, Robert H. G. 1970. The Manchurian Frontier in Ch'ing History. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Liu Shuyong. 1997. "Hong Kong's Economic Development," China Today 46, no. 6: 30--33.

Rowe, William T. 1984. Hankow: Commerce and Society in a Chinese City, 1796-1889. Stanford, Cali.: Stanford University Press.

Schipper, Kristofer M. 1977. "Neighborhood Cult Associations in Traditional Tainan," in The City in Late Imperial China, edited by G. William Skinner, pp. 651-676. Stanford, Cali.: Stanford University Press.

Skinner, G. William. 1977a. "Regional Urbanization in Nineteenth-Century China," in The City in Late Imperial China, edited by G. W. Skinner, pp. 211-249. Stanford Cali.: Stanford University Press.

—.1977b. "Cities and the Hierarchy of Local Systems," in The City in Late Imperial China, edited by G. W. Skinner, pp. 275-364. Stanford, Cali.: Stanford University Press.

—.1977c. "Urban Social Structure in Ch'ing China," in The City in Late Imperial China, edited by G. W. Skinner, pp. 275-364. Stanford, Cali.: Stanford University Press.

—.1987. "Sichuan's Population in the Nineteenth Century: Lessons from Disaggregated Data." Late Imperial China 8: 1-79.

—.1994 "Differential Development in Lingnan," in The Economic Transformation of South China, edited by Thomas P. Lyons and Victor Nee, pp. 17-54. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell East Asia Program.

Thomson, John. [1873/4] 1982. China and Its People in Early Photographs. New York: Dover.

Unger, Jonathan. 1993. "Urban Families in the Eighties: An Analysis of Chinese Surveys," in Chinese Families in the Post-Mao Era, edited by Deborah Davis and Stevan Harrell, pp. 25-49. Berkeley, Cali.: University of California Press.

Whyte, Martin King. 1993. "Wedding Behavior and Family Strategies in Chengdu," in Chinese Families in Post-Mao China, edited by Deborah Davis and Stevan Harrell, pp. 189-216. Berkeley, Cali.: University of California Press.