|

|

|

|

Cosmopolitan Capitalists: Hong Kong and the Chinese Diaspora at the End of the 20th Century, by Gary G. Hamilton (ed.)

4: Between China and the World

Hong Kong's Economy before and after 1997

Barry Naughton

The People's Republic of China resumed sovereignty over Hong Kong on July 1, 1997, ending 150 years of colonial rule. The transition has multiple historical, cultural, and political implications that will resonate and unfold for a long time. However, for many, the single most striking and surprising aspect of the change is the contrast between the economies of China and of Hong Kong. Although China is taking over Hong Kong, in comparing the two economies, the advantage appears to be always with Hong Kong. Hong Kong's prosperous and successful capitalist market economy was recently ranked number one in the world on a major index of economic freedom (Heritage Foundation). Hong Kong continues to have a strong legal system, which, combined with active anti-corruption efforts, has kept corruption relatively low. And until the recent downturn in Asian economies, Hong Kong enjoyed rapid, sustained economic growth that gave it the highest per capita income–after adjustment for real purchasing power differences–of any economy in Asia. By contrast, China's economy, while rapidly growing, is still poor and inefficient. It is hobbled by residual elements of the mostly discarded socialist system, including a pervasive pattern of government involvement in the economy on all levels, which has inevitably led to serious corruption problems. To be sure, the leaders of China have pledged that Hong Kong's system will remain unchanged for 50 years. But such reassurances only make it more strikingly apparent that the losing system seems to be taking over the winning system. Skeptics ask whether the losers can be trusted to keep their hands off the accumulated gains of the winners. Optimists follow a different line of reasoning: Since the new rulers are dependent on their new subjects for the secrets of success, they can be trusted not to kill the goose that laid the golden egg. In this respect, the emphasis is inevitably on the benefits that Hong Kong can bring to China, and on the closely related question of whether China can enjoy those benefits without destroying the system that created them.

This sharp contrast between the economies of the People's Republic of China and Hong Kong is certainly real, and the interactions between these two distinct economic systems will shape the economic destiny of southern China for the foreseeable future. However, it is also possible to overemphasize and oversimplify the contrast between the two economies, and, as a result, to misunderstand the challenges, threats, and opportunities that Hong Kong faces in the coming years. The economies of Hong Kong and the People's Republic of China have been deeply intertwined for many years. Indeed, it is impossible to understand the recent development of either economy without reference to the other. The synergies generated between the two economies have been greatly beneficial to both, but perhaps especially so to Hong Kong, certainly on a per capita basis. The increasingly dense network of interactions between these two jurisdictions means that while the two maintain many separate characteristics, they have long since ceased to be two separate economies and in many respects form a single complexly interdependent unity. Inevitably, this means that the spectacular economic success of Hong Kong depends at least partially on its relations with China. A crucial issue for Hong Kong is thus whether it will be able to maintain its privileged position vis-à-vis China in the future. Future challenges will depend primarily on the changing balance of interests and incentives within this complicated relationship, rather than simply on the extent to which Chinese government policies impinge on the freewheeling Hong Kong economy. 1

In order to provide a glimpse into this complex economic relationship, this chapter looks at the Hong Kong-China economic relationship from a variety of different perspectives. First, I will discuss Hong Kong's role as the entrepôt and gateway to China, and examine the changing balance between trade and manufacturing in the Hong Kong economy. This section presents what might be thought of as the ordinary economics of the Hong Kong-China relationship. It examines the growth of trade and investment, the dramatic restructuring of the Hong Kong economy, and the enormous interdependence that already exists between Hong Kong and China. The second section probes one of the deeper strata in the relationship between Hong Kong and China, stressing the major flows of investment that link the two. While it is well known that Hong Kong is the largest "foreign" investor in China, it is less commonly stressed that China is also the largest "foreign" investor in Hong Kong. There is a substantial two-way flow between the two. An important feature of these two-way flows is the ability of Hong Kong actors to engage in what I call "property rights arbitrage." For a long time, Hong Kong agents have been in a peculiarly advantageous position to profit from the distortions and partial openings of China's economic reform. One result has been large inflows of capital from China to Hong Kong.

The third section takes off from the observations of the previous section. The existence of property rights arbitrage means that Hong Kong has been in the position to earn substantial locational rents from its relationship with China. That is, by virtue of its unique position, businesses and individuals in Hong Kong are able to earn above-normal returns on their skills and efforts, as well as on some of their assets. The overall level of locational rents is increased by some of the peculiar incentives that Beijing possesses vis-à-vis Hong Kong: since Hong Kong's retrocession is widely regarded as a bellwether of Beijing's ability to manage a complex, internationally dependent market economy, Beijing has an enormous incentive to stabilize and guarantee the prosperity of Hong Kong. Inevitably, the process of stabilization costs money, and some of that money flows into the pockets of Hong Kong people.

In the final section, I speculate on the implications of the preceding analysis for Hong Kong's role in the world economy. Hong Kong's future depends not simply on whether China can keep its hands off Hong Kong's prosperity but more importantly on the specific features of the relationship between China and Hong Kong. Hong Kong, I argue, is torn between a steadily deepening involvement with China and the need to increase its efficiency as a world city. To a certain extent, these trajectories conflict. The only way they can be reconciled is through further reform and social progress in China.

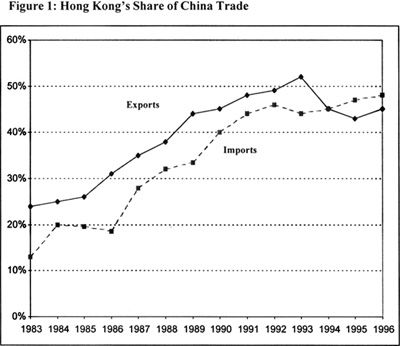

The Hong Kong Paradox

Yun-wing Sung has written extensively about what he calls the "Hong Kong paradox." The paradox consists of the following: Before China began economic reforms, a significant proportion of China's external trade–and especially of China's exports–was channeled through Hong Kong. One would have expected that liberalization in China would lead to a proliferation of opportunities and channels for export and import, and rapid growth of trade in all parts of China. Therefore, one would expect that although trade between Hong Kong and China would grow rapidly, Hong Kong's relative position in China's trade would decrease, simply because of the relatively faster rise of alternate trade opportunities. Instead, the opposite happened: between 1978 and 1993, the proportion of China's trade sent to or through Hong Kong increased steadily and dramatically from 11 percent to 48 percent. The share of Chinese exports going through Hong Kong increased from 21 percent to 52 percent (see figure 1). For Sung, this paradoxical result reflects, above all, the outstanding efficiency of the Hong Kong economy and the presence of economies of scale and scope in an urban center. In Sung's analysis, Hong Kong has attracted the bulk of China's trade to itself simply because it so efficient in carrying out the role of middleman (Yun-wing Sung 1991a, 1991b, 1997).

Sung's pathbreaking analysis provides the elements necessary to understand the Hong Kong-China relationship. We can build further on his analysis to point out that Hong Kong's growing role in China trade is due not only to Hong Kong's efficiency as a trader but also to the simple fact that much of "China trade" is in fact a geographic displacement of past "Hong Kong trade." That is, Hong Kong's success as the key China trader is, in fact, founded upon Hong Kong's past success as a manufacturer and upon the transfer of Hong Kong manufacturing capacity to China, especially to Guangdong province. This presents us with a complete historical cycle: Hong Kong first established its prosperity in the nineteenth century by serving as an entrepôt for the China trade and had little or no manufacturing capability. As this section will show, Hong Kong's evolution has essentially been from entrepôt to entrepôt in three generations.

Hong Kong did not develop significant manufacturing capabilities until after 1949. Indeed, Hong Kong indirectly owes its initial manufacturing base to the Chinese Communist Party, because the initial seeds of Hong Kong manufacturing were planted by emigrant industrialists from Shanghai immediately following the 1949 revolution (Wong Siu-lun 1988). Shanghai industrialists brought their familiarity with modern labor-intensive manufacturing, especially in the textile industry. These skills meshed nicely with Hong Kong's existing commercial networks, which were accustomed to transmitting the demands and caprices of world markets to local producers. New industries grew up alongside the transplanted Shanghai textile industry: plastic flowers and rattan furniture led gradually to electronics and precision machinery (Turner 1996). By the early 1980s, it was common to think of Hong Kong as predominantly a producer and exporter of labor-intensive manufactures, and the manufacturing labor force totaled almost a million workers.

During the mid-1980s, economic reforms in China opened up the China coastal region to foreign investment and trade just at the time when rising wages and costs and currency realignments were creating pressures to restructure for exporters in the successful East Asian newly industrializing countries (NICs), including Taiwan, Korea, and Singapore, as well as Hong Kong. Hong Kong businesses were extremely well placed to take advantage of this opportunity, and they responded with a flood of business into the People's Republic of China (PRC), especially into neighboring Guangdong province. Hong Kong investment poured into Guangdong, creating thousands of new foreign-invested enterprises, many of them exporters. Moreover, Hong Kong businesses pioneered new trade arrangements of "outward processing," by which they supplied raw materials and components to Chinese domestic enterprises (often township and village enterprises) for processing and re-export. Thus, there was a massive transfer of manufacturing capacity to the PRC, and especially to Guangdong province.

In 1985, Guangdong produced only 11 percent of China's exports (including most of the 1 percent of exports produced by foreign-invested firms). By 1994, Guangdong produced a staggering 44 percent of China's total exports. Foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) had grown to produce nearly 30 percent of China's exports, and Guangdong produced more than half of all of those exports. Perhaps even more impressive, Guangdong's domestic enterprises (state-owned firms, collectives, and, increasingly, private firms) had increased their share of Chinese domestic exports (i.e., those not produced by FIEs) to 39 percent (China General Administration of Customs). Thus, behind the growing role of Hong Kong in China's foreign trade is Guangdong's growing role in China's export production. A massive transfer and buildup of capacity has occurred in Guangdong. Since Hong Kong is the natural export outlet for Guangdong manufacturing capacity, it is not surprising that Hong Kong's importance in trade has increased along with Guangdong's growth in manufacturing. More fundamentally, Guangdong's development is itself the result of the restructuring and geographic expansion of Hong Kong's existing manufacturing networks (Naughton 1996).

In turn, that restructuring has fundamentally transformed the nature of the Hong Kong economy. Most obviously, the importance of manufacturing carried out within Hong Kong has declined dramatically. The manufacturing labor force has fallen by over 60 percent, from nearly a 1,000,000 to only 386,000 at the end of 1995, which represents a drop of from 45 percent to 16 percent of the workforce. Hong Kong itself is increasingly specialized in business services, providing finance, marketing, transport, and communications services to an industrial economy that sprawls throughout Guangdong, and increasingly throughout the entire China mainland.

During the years 1995-1997–the runup to Chinese resumption of sovereignty over Hong Kong–the growth of this industrial complex slowed substantially. Some slowdown was inevitable, simply because the restructuring process had been so thorough. There are simply not that many labor-intensive producers left in Hong Kong–most such activity has already been relocated to neighboring Guangdong province. But other factors are at work as well. Rapid growth has pushed up wages and other costs inside China, and especially in Guangdong, reducing export competitiveness. Nevertheless, additional foreign investment, drawn by the lure of the vast China market, continues to pour in, and the inflow of capital has tended to keep the Chinese currency appreciating in real terms, further squeezing exporters (Naughton 1996). In Guangdong, economic success has led to increasing congestion and rising costs. Guangdong's share of Chinese exports declined after 1994, reflecting reductions in Guangdong's share both of domestic firm exports (from 39 percent to 33 percent in 1996) and of FIE exports (from 57 percent to 49.9 percent) in two years.

Thus, the economies of Hong Kong and (at least) Guangdong are already highly integrated. Integrating these two disparate economic systems is not the challenge facing Hong Kong post-1997. Rather, the challenge is to improve the productivity and competitiveness of an existing export economy. The export economy is centered on Hong Kong but sprawls across the border into Guangdong. The export complex has lost the benefits of extremely low labor costs that provided the basis for the first period of very rapid growth. It now needs to find a basis for enhanced competitiveness by improving efficiency and technological capacity.

Property Rights Arbitrage

At the same time that the restructuring of Hong Kong manufacturing has taken place, the opening of China has created another type of opportunity for Hong Kong. This is the opportunity to engage in what I call "property rights arbitrage." In this business, Hong Kong residents profit from the existence in Hong Kong of a secure and transparent system of property rights, in close proximity to the vague and uncertain property rights regime in China. Hong Kong has benefited from the wholesale transplantation of the British property rights regime and the full panoply of supporting legal and commercial institutions, which evolved in Britain over hundreds of years. An effective and generally fair judiciary, with clear enforcement powers, was supplemented in 1974 by the creation of the powerful Independent Commission Against Corruption (Chan 1997). As a result, commercial transactions in Hong Kong take place in a legal regime that is as clear and transparent as any developed market economy. By contrast, despite the progress that has been made in China during nearly 20 years of economic reform, property rights there remain vague, difficult or impossible to enforce, and always ultimately uncertain. Distribution of ownership and control rights is rarely precise, and interested parties only occasionally have recourse to third-party adjudication in disputes about control rights. Even when courts can be brought in to make civil judgments (as in contract disputes), they are often unable to enforce their judgments (Clarke 1996), which results in a persistent demand within China for secure property rights. Hong Kong, by virtue of its proximity to China, its cultural similarities, and its excellent property rights regime is in a position to satisfy this demand.

PRC residents come to Hong Kong in a steady stream, looking for opportunities to transform assets over which they have uncertain claim into secure and liquid assets. In return, these PRC residents are prepared to provide "inside information," which they possess in abundance, to those who can assist them. The basic act of arbitrage is the exchange of inside information for the opportunity to transform existing control rights into secure ownership under Hong Kong's legal system. Inside information should be understood here as knowledge about economic opportunities–both socially productive and socially unproductive–which those residents would exploit openly if they had access to secure property rights over the return thereby generated. PRC residents may hesitate to exploit these opportunities in the absence of secure claims over the resulting return. However, they will be happy to share those opportunities with "outsiders" who can offer them a secure claim to a portion of the resulting returns. In the current Chinese context, those outsiders are often from Hong Kong.

There is a broad spectrum of activities that fit into this general description. At one extreme, Hong Kong serves as a safe haven for assets plundered from the public. Exploiting political position and family ties, individuals in the PRC move essentially stolen capital into Hong Kong, where nobody asks questions. At the other end of the spectrum, public and privately owned businesses in China move assets to Hong Kong in order to increase their operational autonomy, learn about new property rights procedures, and access information about the world market. In the latter case, formal ownership doesn't change, but the way that ownership is exercised does. In this situation, even publicly owned corporations can benefit from the Hong Kong property rights regime, since it provides a set of procedures and examples for specifying control rights and thereby improving managerial autonomy and incentives.

It is important to maintain the right balance between cynicism and enthusiasm in examining the process of property rights arbitrage. This process includes both laundering (money) and learning (new commercial institutions), as well as many other activities in between. For example, even state-owned firms in China maneuver to gain greater autonomy and more secure managerial control over their own assets. When they establish Hong Kong subsidiaries, those subsidiaries can invest back in China with the status of "foreign investors." Ventures entered into in China by these bogus foreigners (jia yangguizi) qualify for tax breaks and expanded autonomy. This round-tripping of investment is sometimes referred to with a snicker, as if the economic transactions being reported were somehow phony or inflated. In fact, such transactions are an important part of the success of China's economic reforms. Public enterprises maneuver for greater autonomy, and in the process establish new institutional forms–and new forms of accountability–that contribute to the transition to a new property rights regime within China.

Indeed, the establishment of a stronger and more clearly specified property rights regime is a necessary part of the transition to an open market economy. Every economy making the transition from socialism faces difficult decisions about the extent to which state-appointed managers may be allowed to transform their effective political control over nominally public assets into private ownership. In the long run, the transition to a market economy clearly and inevitably implies the conversion of most formerly public assets into private property. While it would be nice to think that this process could be entirely fair, it is unlikely that it ever will be. Some managers will be able to convert a portion of the value of assets they control into their own private property. Moreover, even in a perfect world, it would probably not be desirable to reduce to zero the incidence of such conversion of public assets to private ownership. To do so would simply do too much to inhibit the development of productive potential by those in a position to identify and exploit it. Thus, in China, as in other transitional economies, there will always be politically powerful and influential individuals who are able to convert their privileged positions into economically valuable assets. What is distinctive about China is that Hong Kong is so clearly the superior venue in which to carry out this transformation. 2

We can gain important insight into the process of property rights arbitrage by examining Chinese firms in Hong Kong. By early 1997, there were about 3,700 Chinese enterprises in China, active in all sectors and pursuing a variety of objectives and commercial strategies (Huchet 1997; also Wong 1993). The mainland firms in Hong Kong that have attracted the most attention lately are the so-called red chips. The term refers to 62 firms with a predominant PRC ownership stake, which are now based in Hong Kong and are listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange. During 1996, the red chips appreciated by an average of 70 percent, significantly outperforming the booming Hong Kong market. By the spring of 1997, the red chips accounted for more than 7 percent of Hong Kong's stock market capitalization and were again outperforming the market in the runup to July 1. Of course, listing on the Hong Kong exchange is a way for these firms to attract financing, and indeed, over $1.4 billion was raised in 1996-97. But this capital is attracted with the expectation of access to mainland China properties. Indeed, according to one calculation, the total valuation of the red chips, at $32 billion, reflects an "excess" valuation of $11 billion relative to the market's average price-earnings ratio. This reflects both the implicit valuation placed by the market on the red chips' politically influential connections and the expectation that mainland parents will transfer significant assets to their subsidiaries. "Large goodwill premiums may be justified if an influential Chinese parent is likely to inject underpriced assets in exchange for over-priced shares in its listed subsidiary, as happened with CITIC Pacific." ("Red chips" 1997; Ridding 1997). Alternately stated, red chips are favored by the Hong Kong stock market because they are viewed as a way for the average investor to participate in the ongoing process of property rights arbitrage.

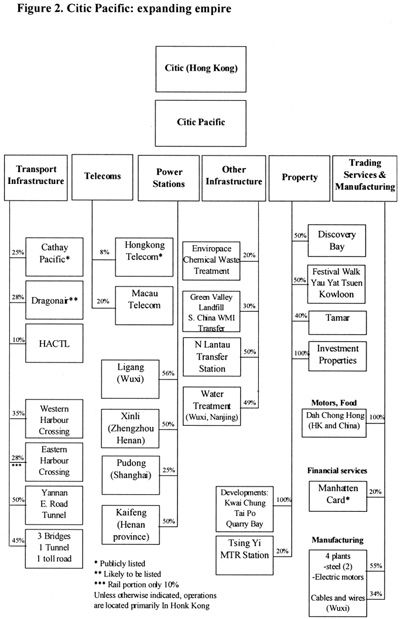

CITIC Pacific is by far the largest of the red chips, with a stock market capitalization equivalent to over US$10 billion in May 1997. Its holdings are extensive (see figure 2), and CITIC Pacific has gradually expanded its investments to give it a large stake in the regulated monopolies of the Hong Kong economy. In early 1997, CITIC Pacific had substantial stakes in both of Hong Kong's airlines (Cathay Pacific and Dragonair), Hongkong Telecom, and Hong Kong Light and Power. 3 These deals–all joint ventures with existing Hong Kong companies–provide interesting benefits to both sides. CITIC Pacific can claim, with some justification, to be investing in infrastructure in Hong Kong and the mainland, as Chinese policy deems preferable. CITIC Pacific's partners hope to gain an influential partner in Beijing, so they have a clear pipeline to exert influence. At the same time, CITIC Pacific often appeared to get "sweetheart" deals in its purchase of stakes for precisely this reason. 4

A second aspect of Hong Kong business can be loosely grouped under the rubric of property rights arbitrage. Hong Kong has developed an enormous business providing information about China to the world business community. Just as China's property rights regime is opaque, so information about commercial opportunities in China is sketchy and difficult to interpret. Hong Kong firms and individuals serve as middlemen, introducing foreign companies to opportunities and partners in China. Some of this is pure consulting work, translating terms and legal concepts into Western languages. But much of it is far more extensive deal making. Hong Kong firms serve as investment bankers, matching up foreign businesses and Chinese clients. Some of this can be quite lucrative.

The operations of the U.S. transnational corporation Avon Cosmetics is an example of this type of activity. Avon tried without success for several years to get into China. Ultimately, the company went through a Hong Kong banker, David Li of the Bank of East Asia, who was able to structure a deal with a small Guangzhou cosmetics factory and obtain the necessary approvals. In return, Li and a Hong Kong associate received 5 percent of the value of the resulting joint venture, which is now a substantial business (White 1991; Laidler 1994). Clearly, Li provided real information and assistance of substantial value to Avon. More crucially, he was also able to provide something useful to the relevant decisionmakers in China. After all, they could simply have accepted Avon's earlier overtures, but something was lacking, presumably the opportunity to attract all the necessary decisionmakers to a package that offered something for each of them. Li was able to succeed not only because he could determine who all the relevant decisionmakers were, but also because he could structure a deal that had something for all of them. Undoubtedly, he was assisted in this process by the abundant, secure opportunities in Hong Kong, to which he could make explicit or implicit promises of access.

Most of the property rights arbitrage in which Hong Kong has engaged has probably resulted in increased productive activity and improved living conditions for the people of Guangdong, Beijing, and Hong Kong. The gains made from opening up China and combining available low-cost labor with world markets and capital were simply so enormous that even if individuals skimmed off part of the benefit, there was plenty left for the public good. Hong Kong has played a significant role in this process. It is not quite enough to say that Hong Kong benefited from the rule of law and secure property rights; it did so benefit, but it benefited even more from the fortuitous combination of protected property rights in Hong Kong and insecure property rights inside a China in transition.

A final type of transaction that might perhaps be placed under the general rubric of property rights arbitrage is smuggling. Granted that smuggling is different in kind from the activities previously discussed, it does bear some important similarities. Goods are brought into Hong Kong legally, efficiently, and cheaply and required only one quick and relatively inexpensive step to be smuggled into China. Smuggling is lucrative precisely because legal imports to China are limited by high tariffs and a tangle of difficult-to-navigate administrative restrictions. Again, Hong Kong earns locational rents from its position as the superior jumping-off station for smuggling into China. Huge contraband traffic flows are known to exist in cigarettes (Smith 1996), fruit (Iritani 1997), and consumer electronics (Huang 1993). In all these instances, Hong Kong agents play a pivotal role and earn substantial revenues.

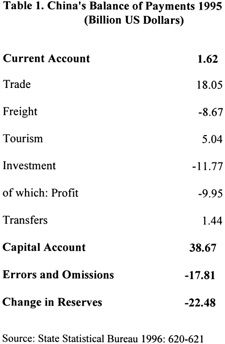

It is appropriate to end this section by reviewing the overall magnitude of the processes discussed above. Some idea of the relevant magnitudes can be achieved from examining China's balance of payments (Table 1). In 1995, China's current account was approximately in balance. A trade surplus of $18 billion was enough to pay for freight charges of almost $9 billion and profit remittances of $10 billion. Hong Kong, as a service provider, was a major earner of freight charges and a major recipient of profit remittances. Capital poured into China, almost $39 billion. But despite the balanced current account, China's foreign exchange reserves increased only $22.5 billion. Errors and omissions added up to a staggering $17.8 billion net outflow (errors and omissions have been approximately $10 billion or more since 1993). Errors and omissions were equal to about 12 percent of China's total exports and equivalent to the total export surplus. Errors and omissions basically reflect three factors: (1) smuggling into China, (2) flight of capital out of China, and (3) services purchased outside of China that do not get recorded by the formal statistical system. A plausible guess might be that the above list reflects the relative ranking of factors as well. For our purposes, what is important is that in each of these flows, Hong Kong agents play a crucial and lucrative role. 5

Hong Kong's entanglement with the Chinese economy permits us to trace other interactions as well. One important way in which capital is moved across borders covertly is through over-invoicing of imports and under-invoicing of exports. There is no simple way to detect under-invoicing but there are some interesting numbers that allow us to estimate the joint impact of under-invoicing and the real economic advantages that Hong Kong possesses. In 1995, Hong Kong imported US$67.2 billion of commodities from China and re-exported $82.3 billion of Chinese commodities (Census and Statistics Department 1996: 80). This is not impossible. Hong Kong shippers and marketers add value to commodities brought in from China. However, keeping in mind that about 8 percent of Chinese imports are retained in Hong Kong, these numbers, taken at face value, would imply that Hong Kong re-exports added, on average, 33 percent to the value of commodities from China. This is a lot of value to add, and the relationship does not hold for any other country's re-exports through Hong Kong.

Consider a related set of numbers. In the same year, exporters inside China imported US$58.4 billion worth of duty-free components and raw materials for export production. Most of these exporters were foreign-invested firms; most of the foreign investment comes from Hong Kong. These producers then exported commodities made with duty-free imports to the value of $73.7 billion (not all of this through Hong Kong). That is, the value of their exports was 26 percent greater than the value of their imports (General Administration of Customs 1995). These data imply that for goods "manufactured in China" and re-exported through Hong Kong, a greater share of the value is retained in Hong Kong than is retained in China. 6 While we cannot say anything definitive about who ought to be earning the net revenues from exporting, we can say that the agents who control the transactions choose to have the majority of those net revenues accrue in Hong Kong, even though the bulk of the manufacturing activity, at least, is performed inside China. 7 Moreover, we can begin to understand another piece of the "Hong Kong paradox." Hong Kong has increased its share of China's trade despite reform in part because traders prefer to divert transactions to Hong Kong in order to take advantage of Hong Kong's more accommodating property rights regime.

The Emerging Partnership Between Hong Kong And Beijing

The previous section discussed the impact of property rights arbitrage, an activity that reflects the interests of individuals and individual businesses or organizations. In addition, though, economic exchanges between China and Hong Kong are influenced by the interests of the Beijing government through officials acting in an official capacity.

Politically, the return of Hong Kong is an event of great importance. If it is bungled, it will reflect extremely poorly on the Beijing leaders who are responsible. No individual Beijing leader is likely to survive politically if he appears to have mishandled Hong Kong's prosperity. Moreover, because the PRC is a huge investor in Hong Kong through thousands of legitimate and illegitimate, public and private channels, and because Hong Kong is so important to China's export economy, there are substantial reasons to try to guarantee the economic functioning of Hong Kong.

As a result of these intersecting political, economic, and personal factors, the PRC is far more likely to try to prop up the Hong Kong economy in case of adversity than it is to try to extract resources from it. In that respect, the post-1997 reality will be a continuation of the pre-1997 reality. The Beijing government will step in to insulate the Hong Kong economy from some of the fluctuations occasionally induced by its free-market economy. Indeed, Beijing has already earmarked a potential "rescue fund" to shore up the Hong Kong stock exchange. This follows earlier Chinese intervention in October 1987 and June 1989 to protect the Hong Kong market in the face of external shocks, of U.S. and Chinese origin, respectively (Lucas 1996). In the sphere of currency intervention, the Asian business crisis revealed China's resolve to hold to its agreement to support the Hong Kong dollar, even while promising that Hong Kong funds will not be used to rescue the PRC in case of fluctuations there (Sheng 1997). According to one insider account, during the first half of 1997–the runup to the July 1 retrocession–Beijing spent the equivalent in Hong Kong dollars of US$12 billion in order to support the property and stock markets in Hong Kong (Luo Bing 1997).

For the Chinese government, such investments have a dual motivation. The first is simply to stabilize a potentially unstable market, in a situation in which instability would have adverse consequences for Chinese policy. The second motivation is to secure what the Chinese government sees as "strategic" influence over the Hong Kong economy. Chinese leaders unquestionably see the Hong Kong economy as dominated by U.S. and British corporations, including long-standing Hong Kong corporations that are descendants of British hongs. In this respect, the Chinese government engineered a stunning conversion of control over Hong Kong's strategic industries in little more than a year. Beginning with the purchase in April 1996 of a stake in Cathay Pacific Airlines, Hong Kong's flag carrier, and ending with the purchase in June 1997 of 5.5 percent of Hongkong Telecom by China Telecom, close affiliates of the Beijing government gained a minority interest in all the main utilities and communications firms in Hong Kong.

The expansion of Beijing interests in Hong Kong inevitably implies a flow of resources into Hong Kong. Initially, this may not be evident, because Beijing has been able to acquire many of these assets at bargain prices, because China is and will continue to be an enormous opportunity for businesses in Hong Kong. Thus, the owners of each of Hong Kong's strategic industries were willing to pass on a minority stake at bargain prices, perceiving this transaction as a way to open the door to further business on the Chinese mainland. Currently, a wave of restructuring is taking place in Hong Kong, as businesses there try to position themselves to benefit from future opportunities in the new policy environment. Many Hong Kong corporations, most notably Li Kashing's Cheung Kong Holdings, are going through restructuring processes designed to position them closer to channels of influence leading to Beijing and thus able to take advantage of new opportunities decided increasingly by the government in Beijing. This is generally not a defensive restructuring, but rather an aggressive effort to position companies to take advantage of new opportunities. Private interests seek to accommodate Chinese government interests and to profit thereby. Profit may be particularly easy to attain because the Beijing government also seeks to woo Hong Kong capitalists to support the new regime. In this respect, Beijing seeks to replicate the traditional British power structure and ensure a policy in which business interests are the primary support of the post-1997 regime (Beja 1997).

The Future?

What, then, of Hong Kong's future? I hope the preceding pages have convinced the reader that Hong Kong's economy is already engaged in a complex, multifaceted collaboration with businesses and government in the PRC. As a result, we cannot reasonably reduce the question of Hong Kong's economic future to the question of whether China will be able to leave Hong Kong's economic system alone to flourish. An alternative perspective would be to see Hong Kong as poised between two contrasting economic futures: Hong Kong-International and Hong Kong-China (Business and Professionals Federation of Hong Kong, 1993). Hong Kong has been remarkably successful as an international city, building first an export base and subsequently an international service corporation of exemplary efficiency. Particularly since the mid-1980s, the success of Hong Kong-International has been reinforced by the lucrative and successful business of Hong Kong-China, as Hong Kong has reaped the locational rents provided by its unique access to the emerging Chinese market and production base.

As of 1997, the two alternative visions of Hong Kong-International and Hong Kong-China are beginning to show signs of conflict. One source of conflict is purely economic. As described above, rising costs are eroding the competitiveness of the Hong Kong-Guangdong export complex, even as further market openings within China attract more foreign (and Hong Kong) investment to China. As a result, the appeal of business in China is increasingly drawing Hong Kong businesses, and especially the biggest Hong Kong businesses, into tight collaboration with the PRC. The danger of an excessive orientation toward China exists, not because of governmental controls but because of the very lucrative opportunities that continue to be found there.

Moreover, if economic reforms in China stall, Hong Kong agents will continue to engage in property rights arbitrage, but ultimately this will hurt them. Resources will continue to flow into Hong Kong so long as the PRC cannot provide secure property rights. However, in order to protect mainland businesses, Hong Kong companies would be drawn more and more deeply into corrupt arrangements in China, and further and further away from the alternative future envisaged in "Hong Kong-International." Moreover, in this type of scenario, as Huchet (1997) points out, even as Hong Kong retains its overall prosperity, Hong Kong companies will have less of a comparative advantage over Chinese companies in Hong Kong. Chinese enterprises in Hong Kong are better prepared, Huchet argues, to process Chinese economic interests in Hong Kong. The lure of real opportunity combined with special privileges may draw Hong Kong into an intensified collaboration with China that might cause Hong Kong to become less oriented toward providing efficient commercial and intermediary services to the East Asian region as a whole. Hong Kong is still small: its labor force and land area are tiny, and it probably cannot be all things to all people. If its political and economic leaders pursue the vision of a Hong Kong that predominantly serves the Chinese economy, this will almost certainly mean a relative diminution in Hong Kong's international role. This does not necessarily mean a less prosperous, or an unhappy, Hong Kong. But it might mean one that plays a less distinctive role in the world economy than Hong Kong does today.

One path through which this might occur is an interventionist attempt to build Hong Kong's technological capability in order to infuse the Hong Kong-centered manufacturing network with an additional competitive advantage. Moreover, pressures to do so are inevitable, given the rising costs being experienced in the Hong Kong-Guangdong production complex and the apparent decline in the rapid growth of labor-intensive manufactured exports. Recently, two major studies, commissioned by important Hong Kong agencies, have recommended related policies (Berger and Lester 1997; Enright 1997). Such proposals for an activist government policy to foster technological upgrading are said to regarded favorably by the new chief executive, C. H. Tung ("Riding the Next Industrial Wave," 1997). Government support for such an industrial policy, combined with concessionary access to opportunities on the mainland, could prove an irresistible lure for Hong Kong businesses.

On balance, this scenario would be somewhat negative for Hong Kong's development, and indirectly for that of China. China would be better served by a more comprehensive opening up, rather than a type of "hothouse development" with Hong Kong playing a catalytic, but controlled, role. Hong Kong's past movement from entrepôt to manufacturing power to entrepôt shows that the past does not determine the future. With the benefit of good human skills and physical infrastructure, Hong Kong, like any successful economy, should be able to remake itself over and over again, adapting to the changing mix of opportunities and challenges. Moreover, Hong Kong residents have dispersed around the globe, constituting an international network of potentially huge value to Hong Kong's future development.

In an alternative scenario, further reforms in China would make Hong Kong's position less special. Hong Kong would enjoy fewer locational rents, and there would be a smaller influx of flight capital and strategic investments. Hong Kong's property market, still expensive despite easing off during the Asian business crisis, might continue to lose more of its value because it would not be necessary to concentrate so many activities in Hong Kong's tiny land space. But in compensation, Hong Kong's prosperity would ultimately be less precarious than in the first scenario. Hong Kong companies and individuals would be able to bring their skills into play throughout China and the world. Rather than managing the Hong Kong-Guangdong export complex, Hong Kong people would serve as catalysts for a broad-based process of economic growth throughout southern China. In a dynamic growth process of this kind, the conflict between Hong Kong--China and Hong Kong-International would be less fundamental, and Hong Kong would be able to mediate a productive development synthesizing the needs of both.

Notes

Note 1: For example, the tendency to see the Chinese and Hong Kong economies as fundamentally separate recently led the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, Newt Gingrich, to propose using China's most favored nation (MFN) trading status as a reward for good Chinese behavior toward Hong Kong. Gingrich proposed a six-month conditional MFN status for China, while its behavior toward Hong Kong was closely monitored. The problem with using MFN status as a reward or punishment for China's conduct toward Hong Kong is that it fails to recognize that the economies are so intertwined that cancellation of the MFN designation for China would be even more devastating for Hong Kong. Gingrich's proposed sanction provoked the polite, but essentially caustic, reminder from Chris Patton that "for the people of Hong Kong there is no comfort in the proposition that if China reduces their freedoms, the United States will take away their jobs." Paul Blustein and John E. Yang, "Hong Kong Leaders Reject GOP Plan," Washington Post, May 9, 1997, p. 1.Back.

Note 2: In any case, the weak property rights and unfair distribution of control over nominally public assets that create this profitable arbitrage are, after all, characteristics of the PRC legal regime, not that of Hong Kong. There is no point in blaming Hong Kong for it.Back.

Note 3: The stake in Hongkong Telecom was sold to another red chip, China Everbright in May 1997. China Everbright might plausibly be considered to have even closer ties to the current Beijing leadership than CITIC Pacific. Since Cable & Wireless, the parent of Hongkong Telecom, subsequently sold an additional 5.5 percent stake to China Telecom, a corporation wholly owned by the Chinese Ministry of Post and Telecommunications, it is reasonable to interpret this subsequent reshuffling of assets as bringing Hongkong Telecom more directly into the sphere of Chinese government interest.Back.

Note 4: Ironically, the head of CITIC Pacific, Larry Yung, is often labeled a "princeling" who traded on the influence of his family, since his father Rong Yiren, besides being the founder of CITIC, the Beijing parent of CITIC Pacific, was also a vice president of China. However, this criticism is misguided. Rong Yiren was first and foremost a Shanghai capitalist who chose to stay in Shanghai while most of the rest of his family relocated to Hong Kong (see Wong Siu-lun 1988). For this service he was–after the tribulations of the Cultural Revolution–rewarded with money and influence. But this did not thereby bring his family into the inner circle of Communist Party leaders.Back.

Note 5: See Gunter (1996) for a heroic attempt to untangle some of the factors relating to capital flight from the PRC.Back.

Note 6: The fit between these two sets of numbers is not perfect. The Chinese numbers refer to transactions that are known in Hong Kong as "outward processing." Outward processing accounted for an estimated 82 percent of Hong Kong's re-exports of Chinese origin in 1995. Thus, while no precise comparison between the numbers is possible (or attempted here), they refer to broad categories of goods that generally overlap.Back.

Note 7: There is no point in going further to disentangle this data, which reflect a combination of factors. First, because Hong Kong specializes in higher-skilled stages of the value-added chain, it earns much higher returns on its productive inputs and claims a surprisingly large share of total value-added. By contrast, China contributes predominantly unskilled labor, with little earning power. In either case, though, agents based in both China and Hong Kong choose to transfer revenues from China to Hong Kong by understating the value of the commodities shipped from China to Hong Kong (i.e., by "under-invoicing") to take advantage of a favorable taxation and property rights regime. Again, Hong Kong benefits due both to its superior efficiency and its status as a property haven. The figure for value-added within China is also lower because some duty-free imports are diverted to the domestic market and are never used in export production at all. This does not directly affect Hong Kong interests, except to the extent that Hong Kong businesses specialize in such activities. In fact, there is substantial evidence of such activity by specialized Hong Kong businesses, which are called channel providers.Back.

References

Beja, Jean Philippe. 1997. "Hong Kong Two Months before the Handover: One Territory, Two Systems?" China News Analysis 1583, April 15.

Berger, Suzanne, and Richard K. Lester, eds. 1997. Made by Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Business & Professionals Federation of Hong Kong. 1993. Hong Kong 21: A Ten-Year Vision and Agenda for Hong Kong's Economy. Hong Kong: Business & Professionals Federation of Hong Kong.

Census and Statistics Department, Government of Hong Kong. 1996. Annual Review of Hong Kong External Trade 1995. Hong Kong: Census and Statistics Department.

Chan Kin-man. 1997. "Combating Corruption and the ICAC," in The Other Hong Kong Report 1997, edited by Joseph Y.S. Cheng, pp. 101-121. Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong Press.

Clarke, Donald C. 19??."Power and Politics in the Chinese Court System: The Enforcement of Civil Judgments," Columbia Journal of Asian Law 10, no. 1: 1-92.

Enright, Michael J. 1997. Hong Kong Advantage. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

General Administration of Customs. 1995. China Customs Statistics.

Gunter, Frank R. 1996. "Capital Flight from the People's Republic of China," China Economic Review 7, no. 1 (Spring): 77-96.

Heritage Foundation. Report on economic freedom, as reported by Hong Kong Trade and Development Council website at http://www.tdc.org.hk/hktstat/97index.htm.

Huang Weiding. 1992. Zhongguo de Yinxing Jingji (China's Hidden Economy). Beijing: Zhongguo Shangye.

Huchet, Jean-Francois. 1997. "Les entreprises chinoises à Hong Kong: Des partenaires ambigus dans l'avenir du Territoire." Perspectives Chinoises 41 (May/June): 54-66.

Iritani, Evelyn. 1997. "U.S. Orange Trade with China Sour and Sweet," Los Angeles Times, August 12, pp. A1, A6.

Laidler, Nathalie. 1994. "Mary Kay Cosmetics: Asian Market Entry." Harvard Business School Case Study, 9-594-023.

Lucas, Louise. 1996. "Beijing plans fund to shore up Hong Kong market," Financial Times, October 30, p. 6.

Luo Bing. 1997. "Hong Kong: Beijing supports the market with billions," Zhengming 236 (June), translated by Jacques Seurre in Perspectives Chinoises 41, (May/June): 52-53.

Naughton, Barry. 1996. "China's Emergence and Future as a Trading Nation," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2: 273-344.

Pritchard, Simon. 1997. "Way forward is with feet firmly on the floor," South China Morning Post, 1 July, p. B18.

"Red chips" 1997. "The Lex Column," Financial Times, March 27, p. 16.

Ridding, John. 1997. "Red Chips and Dark Horses," Financial Times, February 24, p. 15.

"Riding the Next Industrial Wave," 1997. The Industrialist (February): 11-17.

Sheng, Andrew. 1997. "Hong Kong Will Remain a Free Market after 1997," Transition 8, no. 2 (April): 1-3.

Smith, Craig. 1996. "Smugglers Stoke B.A.T's Cigarette Sales in China: Company Condemns Illicit Trade, but Churns Out Smokes to Supply It," The Wall Street Journal, December 18, p. A16.

Sung Yun-wing. 1991a. "Hong Kong's Economic Value to China," in The Other Hong Kong Report 1991, edited by Sung Yun-wing and Lee Ming-kwan, pp. 477-504. Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong Press.

—. 1991b. The China-Hong Kong Connection: The Key to China's Open Door. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

—. 1997. "Hong Kong and the Economic Integration of the China Circle," in The China Circle: Economics and Technology in the PRC, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, edited by Barry Naughton, pp. 41-80. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institute.

Turner, Matthew. 1996. "Hong Kong Design and the Roots of Sino-American Trade Disputes," Annals of the American Academy 547 (September): 37-53.

White, George. 1991. "Hong Kong Bankers Help Open Doors to China," Los Angeles Times, July 1.

Wong, John. 1992. "PRC Business in Hong Kong: A Prelude to Economic Take-Over?" Institute of East Asian Philosophies Internal Study Paper No. 4 (March), National University of Singapore.

Wong Siu-lun. 1988. Emigrant Entrepreneurs: Shanghai Industrialists in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.