|

|

|

|

Cosmopolitan Capitalists: Hong Kong and the Chinese Diaspora at the End of the 20th Century, by Gary G. Hamilton (ed.)

8: Hong Kong Immigration and the Question of Democracy: Contemporary Struggles over Urban Politics in Vancouver, B.C.

Katharyne Mitchell

In the last two decades, migration levels between Asia and western Canada have risen markedly. One of the most pronounced migration streams has run between the former colony of Hong Kong and the city of Vancouver, British Columbia. The contemporary movement of people between these regions is profoundly different from earlier waves, as it is characterized by large numbers of extremely wealthy migrants. Unlike earlier periods of migration, the current group has left the greater China region not to seek better business opportunities or to escape poverty and persecution but to secure citizenship abroad and to diversify financial portfolios. Leaving Hong Kong in advance of the handover to China in 1997, many of the wealthy migrants moved to Canada primarily as a safeguard against the potential negative ramifications that might result from the political change.

The different character of this migrant group has led to vastly different types of interactions with the pre-existing communities in Vancouver. The new migrants' status as successful businesspeople or professionals has given them an economic and cultural power that was not the case with earlier Chinese migrants. As Wickberg and Wong have shown in other chapters in this volume, prior waves of migrants from the southern China region were primarily poor rural laborers brought in to build railroads and work in labor intensive jobs that no other group of people could do so well and so cheaply. By contrast, the contemporary business and professional migrants have arrived in Canada with a high degree of economic clout, cultural savvy, and "network" capital.

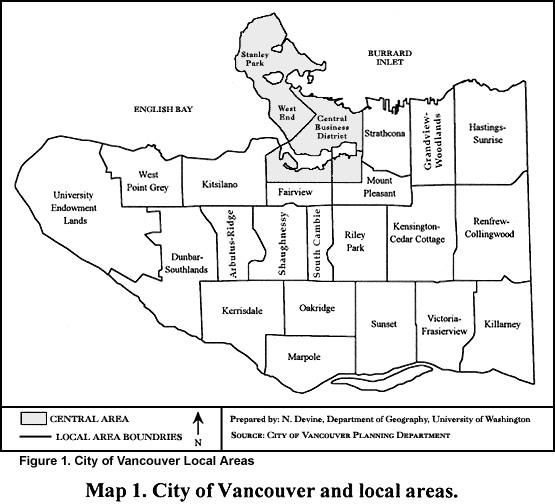

In this paper I discuss the arrival of these new migrants and examine their impact on the democratic values and political institutions of two established communities in Vancouver. The first community, Shaughnessy Heights, is composed of residents of primarily Anglo heritage. The second community, centered in the city's Chinatown, is composed primarily of ethnic Chinese residents. The discussion will concentrate particularly on an analysis of how these new immigrants are able to successfully occupy a western political sphere (in Shaughnessy Heights) yet, seemingly paradoxically, have trouble dominating established Chinese spheres (in Chinatown).

In order to show this, I will narrow my focus by looking at two separate incidents: the first, a series of public hearings on a downzoning amendment in Shaughnessy Heights in 1992; and the second, a vote for the election of new board members to a prominent cultural and political institution in the Chinese community called the Chinese Cultural Center, in 1993. These two moments in the city's recent political history can serve as condensation points for an examination of the differing cultural constructions of and challenges to the concept of democracy that have occurred in the two communities of Vancouver in the last decade.

Democracy, in the sense employed here, is more than just the right to vote and be represented by a government. In both the Shaughnessy Heights and the Chinatown cases, democracy is perceived as a process in which decisions can be made by members of the community as to the best future direction of that community. This type of popular democracy stems from liberal democratic traditions emphasizing the rights of citizens to freely pursue rational debates in a public forum. The public forum, also known as the public sphere, is a space for critical discourse that ideally is open to all citizens concerned with questions of general interest to the public.

In both the case studies discussed in this paper, it is this democratic understanding of a public sphere that is challenged by the new immigrants. In the case of Shaughnessy Heights, the Hong Kong immigrants claimed that they had been shut out of the democratic decision-making process regarding land use in the community, and they demanded and won the right to have a voice in a contemporary downzoning amendment decision. In this way, they succeeded in challenging some of racial and class distinctions that have historically operated to exclude certain citizens from participating on an equal basis in a public forum. They eventually prevented the amendment from passing. In the case of the Chinatown election, by contrast, the recent Hong Kong immigrants were unable to change a democratic system that excluded participation on the basis of particularistic community ties and relationships (a form of insider "nepotism"). Despite the call for more open democratic procedures and equal, rational debate, the immigrants were voted down, and the system of representation remains much as it was prior to the election.

In the following sections, I will briefly document the major movements of people and capital from Hong Kong to Vancouver in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and show some of the ramifications of this movement for the urban environment. Following that, I discuss the ways in which this particular migration wave has affected the political procedures and outcomes of the Shaughnessy Heights downzoning amendment and the Chinese Cultural Center election in the early 1990s. I then draw together these case studies with a more general analysis of the impact of recent Hong Kong immigration on democratic procedures in Vancouver within the two different communities.

Migration And Urban Transformation

Immigration

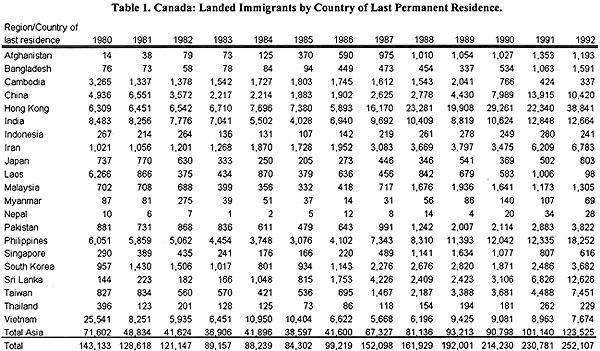

Many scholars have documented the major influx of Hong Kong immigrants into Canada in the last ten years. Immigration statistics show a major leap in immigration in the years following the introduction of a new (business) category of immigration in 1986, and again after the Tiananmen massacre in 1989 (see Table 1). Vancouver, in particular, has been a favorite landing point for Hong Kong immigrants, many of whom are drawn to the city because of the shorter geographical distance to Hong Kong, historical and family ties, and a highly touted quality of life.

An important new component of the immigration program in Canada is a category entitled "business immigration." This category allows investors to skip the processing queue for landed immigrant visas if, among other qualifications, they have a personal net worth of at least C$500,000. Those arriving within the "entrepreneur" category must promise to invest a minimum amount of capital in a Canadian business over a three-year period. For British Columbia, which is known as a "have" province, this amount is C$350,000. Hong Kong has consistently led in this immigration category since it was established in 1986, and Vancouver has once again been a primary recipient of both these business immigrants and their capital funds.

Capital Flows

The exact amounts of capital flows between Hong Kong and Vancouver are not documented by statistical agencies in either city. The business immigrant statistics, however, provide one approximate measure. According to Employment and Immigration Canada, the amount of estimated funds brought to British Columbia in 1988 (most of the funds brought into the province wind up in Vancouver) was nearly 1.5 billion Canadian dollars. Figures from 1989 show an approximate capital flow of C$3.5 billion from Hong Kong to Canada, of which C$2.21 billion, or 63 percent was transferred by the business migration component (Nash 1992; Macdonald 1990).

I consider these figures conservative. Most applicants under-declare their actual resources by a significant margin for income tax purposes. I interviewed bankers and immigration consultants in Hong Kong in 1991 who put the overall amount of funds being transferred from Hong Kong to Canada annually as high as 5 to 6 billion dollars in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Of that amount, nearly one-third would be destined for British Columbia.

Impact On Urban Environment

Many bank officials I interviewed in Hong Kong estimated that most of the funds transferred from Hong Kong to Canada in the late 1980s were invested in property. Despite government attempts to channel capital into productive sectors, the majority of business immigrant funds went into property investment, particularly in the early years of the program. The Financial Post, for example, estimated that in 1990, foreign investment in privately held real estate in Canada nearly tripled from the 1985 figure of US$1.2 billion. If bank financing is included in that figure, the total during 1990 would exceed US$13 billion (Fung 1991).

There have been several repercussions from this capital influx for the built environment. They include a rapid rise in house prices and apartment rates, numerous demolitions of older houses and apartment buildings, and the construction of quite large, boxy houses (termed "monster houses" by the media and local residents) in older neighborhoods (Mitchell 1993, 1997). Many of these houses (some studies show up to 80 percent) were purchased by Hong Kong Chinese buyers, so changes in the neighborhoods often became associated with the influx of people and capital from Hong Kong. These changes have occurred citywide but have been protested most vociferously in westside communities such as Shaughnessy Heights (see Map 1). Residents of this neighborhood have the highest average family income in Vancouver, and census tracks show that the area was almost composed exclusively of white residents of British heritage through the late 1970s.

Exclusive Zoning In Shaughnessy Heights

In the context of massive urban transformations throughout Vancouver in the 1980s, a number of westside community groups arose to resist these changes. The specific emphasis of a majority of these groups was the protection of trees and older houses, but it was part of a much broader struggle to retain the older "character" of the communities, a character predicated on the history, architecture, and values of a British tradition. Historically, Shaughnessy Heights was the most exclusive neighborhood in the city, with numerous specially designed zoning measures and protective covenants that effectively limited residence in the neighborhood to upper-income white families (Mitchell 1994; Ley 1995; Duncan and Duncan 1988). In 1992, there was a major attempt to provide even more protection for this area through further restrictive zoning for the neighborhoods of 2nd and 3rd Shaughnessy. This 1992 amendment would have limited the allowable floor space ratio (FSR) for developers and placed numerous other restrictions on any redevelopment in the area. Before the City Council voted on this amendment, however, the Shaughnessy Heights Property Owners Association (SHPOA) sent out a survey soliciting neighborhood opinion on the amendment and called for a series of public hearings to discuss it.

The Public Hearings Of 1992

I now turn to the most openly confrontational events between the older, Anglo-Canadian residents of Shaughnessy Heights and the more recent Hong Kong Chinese residents in the neighborhood. In six long and agonizing public hearings on the topic of downzoning in South Shaughnessy in 1992, the polarization of these two groups immediately became apparent. In the public hearings, a majority of Shaughnessy Heights Property Owners' Association (SHPOA) members advocated restrictions on future redevelopment in the area. A group composed almost entirely of recent Chinese immigrants from Hong Kong quickly formed an ad hoc committee in opposition to these proposed development restrictions. This ad hoc committee campaigned strenuously against the downzoning. Aided by a number of developers, most prominently Barry Hersh, a house-builder and president of the West Side Builders Association, the campaign used allegations of racism to discredit the SHPOA and its followers. They claimed that the downzoning amendment was actually a veiled effort to keep Chinese buyers from being interested in moving into the neighborhood.

After the first meeting in September, leaflets were sent to Chinese homeowners in the area, urging them to ask Chinese friends from the lower mainland to attend the rest of the hearings in a show of public alliance. These leaflets were written in Chinese, whereas the original survey questionnaire on the topic of downzoning had been written in English only. At the public hearings, Chinese speakers complained that the survey distributed by the Vancouver Planning Department had not been translated into Chinese, reducing the information that they needed to make informed decisions about the proposed change. (By contrast, a neighborhood garbage memorandum had been translated into six languages.) Some of these speakers spoke Cantonese at the hearing and used an interpreter. At several points, they were heckled by Anglo-Canadian members of the audience for not speaking English. The widespread publicity of this racial polarization (The hearings were televised and reported globally) and the manipulation of the definitions of racism by both the Chinese residents and developers indicated new stakes in the battle over urban design and control of the Shaughnessy streetscape. Public hearings are generally presented as models of democratic debate and spaces of rational decision making. But historically most land use decisions have rarely been reached in this way. In Shaughnessy's past, for example, debates over appropriate land use generally led to restrictions based on class and race. The six hearings in 1992 represented the first time that a radically different interpretation of justice and the community good for a westside area was successfully promulgated by a group not composed primarily of Anglo-Canadian residents.

For the first time in the city's history, large numbers of wealthy capitalists who were perceived as "non-white" moved to westside neighborhoods that were formerly protected by virtue of their high prices and exclusive zoning covenants. This outside group was able to form alliances with local capitalists for a pro-growth agenda that threatened the carefully established symbolic value of westside neighborhoods. By raising the specter of racism, which could easily be buttressed by the historical evidence of racism in prior zoning measures, the Hong Kong Chinese and westside builders effectively controlled the public hearings and defeated the SHPOA-designed effort to restrict further development in the neighborhood.

In defense of their position against downzoning, many Chinese speakers extolled the virtues of a perceived Chinese way of life. Rather than contesting cultural differences, however, Chinese homeowners in Shaughnessy used them to their advantage, lecturing enthusiastically about family, respect for the elderly, communal closeness, education, and hard work–and contrasting these values with their representations of lazy, unfamilial, and undemocratic white Canadians. Similarly, they appropriated the meanings of racism and nationalism to their advantage, decrying English only survey forms as inherently un-Canadian, and neighborhood rezoning proposals as manifestly racist.

The understanding of what constituted the community good became a major source of conflict. Definitions of what it meant to be "Canadian" or to "live in Shaughnessy" were opened up for interrogation and negotiation. Rather than simply contesting the Anglo definitions of "Chineseness" and appropriate places for Chinese to live, however, the financial power and cultural savvy of the new group gave them the power to completely invert this process of racial and spatial definition and allowed them to represent dominant Chinese definitions of "Angloness."

The new Chinese homeowners in Shaughnessy were able to ally themselves with developers, realtors, and politicians eager to combine capital in new, increasingly international, business ventures. This slight shifting of the economic and political power ballast in the neighborhood allowed public voicing and material representation of Anglo values and norms from the outsider's perspective. Through this process of contestation and inversion, the formerly undemocratic public forums on land use were exposed as traditional spaces of hegemonic production for an elite (white) group and were successfully transformed by the new immigrants.

To give final weight to this inversion, many of the Chinese residents voiced their concerns in Cantonese and deliberately employed the language of popular democracy in defense of their individual and economic rights. They further spoke of these rights as integral to the Canadian liberal and secular welfare state. In the hearings, much to the dismay of their Anglo-Canadian listeners, Chinese-Canadian speakers invoked notions of freedom, family, individual rights, property rights, and democracy itself in defense of their position. One Chinese-Canadian speaker (using an interpreter) said:

"I live in Shaughnessy and we built a house very much to my liking. The new zoning would not allow enough space for me.... I strongly oppose this new proposal. Why do I have to be inconvenienced by so many regulations? This infringes my freedom. Canada is a democratic country and democracy should be returned to the people." 1

The threat to established norms heralded by this position became clear in an interview with a SHPOA member. She said to me:

"I can't describe to you how it feels to be lectured to about Canadian democracy by people who have to use an interpreter.... Lectured about laziness, how we don't need big houses because we don't take care of our parents like the Chinese do.... I cannot understand how anybody could go to another country and insist they can build against the wishes of an old established neighborhood. The effrontery and the insolence take my breath away." 2

Historic zoning patterns and landscape struggles in Shaughnessy Heights give some indication of how the construction of community spaces has been implicated in the reproduction of a dominant Anglo elite in Vancouver. The contemporary conflict over downzoning also demonstrates how the recent Chinese residents in the community were able to contest and even dominate this urban political sphere in the early 1990s by using alternative concepts of appropriate behavior and justice and by employing the language of individual rights and popular democracy.

The Political Spaces Of The Chinese Cultural Center

My second case study focuses on the impact of recent immigrants from Hong Kong on the political struggle over an important institution within the Chinese community. In this struggle, the question of democracy is raised once again, as many of the new migrants challenge the institutional procedures used in electing new members to the executive board. In this case, the new immigrants again draw from their high economic status and cultural savvy as professionals and businesspeople to attempt to open a supposedly democratic process to more participants. Rather than an exclusivity based on class and race, as in the case of the primarily white neighborhood of Shaughnessy Heights, the Chinese Cultural Center reputedly excluded people on the basis of personal affiliations and other "ascribed" characteristics. In other words, rather than a "modern" democratic system based on principles of equality and achievement, the political system prevailing in the Chinese community was traditionalist in its operation, with authority resting on connection, consensus, and seniority.

In an effort to render the process more democratic and more professional, and thus open up the community to wider participation in a "neutral" public sphere, several recent migrants from Hong Kong and Taiwan ran for office on a platform of political renewal. In their platform, this group professed interest in the democratic reform of a system that they characterized as outmoded, exclusionary, and out of touch with modern organizational principles. Despite their high education and professional status, however, their effort failed. In the following section, I examine this failed effort to revolutionize democratic procedure and the political sphere in Chinatown, then conclude with an analysis comparing the differing community outcomes.

The Democratic Beginnings Of The Chinese Cultural Center

In order to understand how important the Chinese Cultural Center's 1993 election was to the board of directors, it is necessary to know something about the establishment of this institution and its early history. The Chinese Cultural Center (CCC) was established in the early 1970s as an organization that would introduce not just a new cultural forum but also new ways of managing and thinking about community institutions. It arrived on the Chinatown scene as a new political force in direct competition with the older Chinese Benevolent Association (CBA)–an association perceived as stagnant and undemocratic by many younger members of the community.

After it had garnered the support of several prominent professionals and 53 organizations in Chinatown, the early fund-raising efforts by the CCC were extremely successful. This early success, the ambitious plans for a large and central community space, and the democratic leadership style espoused by the founders of the new organization threatened the dominance and traditional authority of the CBA in the political and social affairs of the community. In response to this threat, a smear campaign against the CCC was launched in the Chinese press, in which the CCC was labeled an organization "belonging to the Communist Party." 3

The rancorous debate between the CBA and the CCC spread through the community and began to hinge on the question of democratic representation. Several articles in the Chinese Times, the main Chinatown newspaper through the 1970s, questioned the process by which representatives were elected to the CBA. In these articles, democracy was described as an open, public process, one that was being subverted by a more traditionalist method of governing within the CBA. 4 In the 1970s, the early ideas and values surrounding the Chinese Cultural Center were thus formulated within the context of demands for greater political involvement and a transformation of old-style politics within the community.

The 1993 Elections

In 1993 another major challenge was posed to the established leadership in Chinatown, but this time it was the directors of the Chinese Cultural Center who were attacked for their entrenched and non democratic positions. Despite the Center's early support of the promotion of a more open and democratic process in association elections, by the late 1980s its own board was criticized for perceived insularity and traditionalism. Jane Chan, a lawyer who served on the board during this time period, characterized the CCC board as "not democratic," with "power held by a few." 5 Because of her desire to change these things, Chan, along with 24 other young professionals, campaigned for election to the board of directors in 1993. The group ran under the banner of the Chinese Cultural Center Renewal Committee.

The Renewal Committee, which claimed to be more open and responsive to recent changes in Chinatown (including problems associated with the major influx of people from Hong Kong and Taiwan), was composed entirely of professionals, eight of whom were recent Hong Kong and Taiwanese immigrants who had been in Canada less than 10 years. The Committee challenged the sitting directors of the CCC on two main points: first, the lack of an open, democratic, and professional organizational process (manifested most obviously in an attempt to amend the Center's constitution in 1992); and second, the Center's ongoing political allegiance with the People's Republic of China.

According to Jennifer Lim, a member of the board in 1996, the attempt to render the constitution less democratic was part of a general organizational mode in the CCC in the late 1980s and early 1990s, which was "very inward looking." She believed that "despite the increase in immigrants and new needs" of the community, most of the board was still controlled by elderly individuals who were "locked in" to older cultural values. Lim claimed that the new immigrants were more liberal and open-minded, and wanted to hire professional people and run the association more systematically, less on the basis of favoritism and ascribed relationships. 6 Nelson Tsui, a lawyer and member of the Renewal Committee, said in an interview, "We want the board to be directly accountable; we want the process to be open." He claimed that the politics in older Chinese-Canadian institutions had been based on the traditional Chinese model of respect for authority. But younger immigrants, living in democratic Canada, want "to see that context applied, rather than 5,000 years of Chinese history, which is not democracy." 7

In turn, the Renewal Committee's public allegations of undemocratic procedures and shady financial dealings angered the CCC board, which labeled the new group "elitist social activists" and portrayed them as young, urban, wealthy professionals who were new to Canada, yet wanted to take over from the old pioneers who had built Chinatown. The board and its supporters formed a group called the Committee to Maintain the Community's Participation in the Cultural Center (Maintain). This group began a strong counterattack in which they depicted themselves as more traditional and respectful of history and authority; they claimed to be composed primarily of the older family and regional associations, the Chinatown merchants, and a working class core. In an article defending the CCC board, Executive Director Fred Mah upheld the leadership of the association and spoke against its increased politicization. He represented the CCC board as "moderate" and the Center's positions as "apolitical." 8

Despite the CCC's early origins as a new, invigorating force in Chinatown, however, by the late 1980s it had become entrenched in old-style, traditional politics of authority and consensus. This emphasis culminated in 1992 in the attempt to limit the types of members who could be elected to positions of power on the Board of Directors. It was also evident in the strong desire to seem neutral and "apolitical" in the context of overseas politics. As many Renewal candidates pointed out, however, the decision to attend the PRC banquet in 1989 and not to erect a pro-democracy statue or plaque in the garden were themselves political statements. These kinds of statements were also contested by the Renewal group, which claimed that the Center's politics were not focused on local issues but on the maintenance of strong connections with China.

As with the earlier interrogation of the CBA leadership and its relations with the KMT, the board's economic connections with China were raised and its financial dealings questioned. In both these cases, the money links between regions and individuals and the connection of these links to the construction of a politics of home were brought to the fore by a group claiming some degree of "outsider" status. Their "outsider" status allowed members of the Renewal group to challenge the CCC's old-style politics and connections with China, but it eventually led to their defeat at the polls. Despite a fairly broad representation, Renewal candidates were positioned in campaign flyers, several CCC reports, and editorials as brash and wealthy new arrivals from Hong Kong. And although immigrants from Hong Kong represented a wide spectrum–including refugees, family class migrants, and the working class–the general view of Hong Kong immigrants as arrogant and wealthy was fueled by the influx of business migrants in the late 1980s. This undercurrent of negative feeling about new, "rootless" immigrants who only lived part-time in Vancouver and didn't respect the history of Chinatown or its working-class core was effectively manipulated by the Maintain group. At the prospect of a yuppie "takeover," the old guard of Chinatown closed ranks, upheld a more traditionalist vision of organizational authority, and moved away from the open and self-proclaimed "unselfish and democratic procedures" advocated by members of the Renewal Committee.

Thus, in the 1990s, a group with a large composition of recent Hong Kong and Taiwanese immigrants catalyzed a discussion about democracy and representation similar to the earlier debates of the 1970s, but in this case, the effort to "renew" Chinatown politics failed. The Renewal Committee voiced opposition to the non-democratic and violent authoritarianism of China. They also criticized members of the CCC board for continuing open relations with China in the context of this violence and questioned both the undemocratic political connections and the undemocratic political process they felt was characteristic of the association's leadership. In the context of their arrival in Vancouver, however, many long-term Chinatown residents perceived the challenge as a threat to the very character and history of the community's institutions. The influence of the wealthy business migrants was so great that the general perception of Hong Kong immigrants was largely tied to this group. And because this group represented economic power and urban change on an unprecedented scale, the fear of takeover within the community was correspondingly large.

Concluding Remarks

The Hong Kong emigration to Vancouver in the 1980s and early 1990s was one of many migration streams between Hong Kong and numerous sites around the world. In terms of the movement of a monied class of people, the scale of this migration is unprecedented. Many scholars have examined the economic ramifications as well as the physical and cultural changes that have resulted from the rapid influx of dominant-class fractions into specific areas. But few have begun to analyze the enormous implications for local political systems and outcomes.

One of the most important conclusions that can be drawn from my research to date is the finding that this qualitatively different type of migration does not only affect urban land decisions or the outcomes of political elections. Because of its enormous economic power, coupled with a cosmopolitan and strategic awareness of cultural and political differences worldwide, this migrant group has also been able to impact the democratic process itself in certain instances. Thus, in one neighborhood in Vancouver, the process by which land use decisions had historically been made, a process that was legitimized by reference to equal participation within the public sphere, was forever tarnished, then transformed, by allegations of racism from a group of recent Hong Kong immigrants. This group used the tools of democracy to demand a re-negotiation of the workings of democracy–something quite unusual if not unprecedented for such recent urban arrivals.

However, whereas money, power, network capital, and "outsider" status worked to the advantage of recent Hong Kong immigrants in the struggle over downzoning in Shaughnessy Heights, it appears to have worked to their disadvantage in the political election of the CCC board of directors. Here a key institution within the Chinese community, which had been established originally with specific reference to more open and representative democratic procedures in the 1970s, did not "renew" those democratic commitments in the 1990s. In this case, the perception of longtime Chinatown residents that recent Hong Kong immigrants were arrogant entrepreneurs uninterested in the historical memories and spiritual core of Chinatown was an important factor in the defeat of the Renewal Committee's campaign agenda.

But in juxtaposing these two case studies, let me offer an important caveat to the first conclusion. Although I believe it can be clearly demonstrated that transmigration flows from Hong Kong have had a major impact on urban politics in Vancouver, this impact has taken quite different forms within different communities. The fear of a loss of community "character" as well as the loss of control by an old, established group was expressed in both Shaughnessy Heights and Chinatown, but with differing outcomes. In the first case, a re-negotiation of democratic procedures was forced, partly as a result of a challenge that relied on references to the traditional ideals of a state founded on the principles of liberalism. In the face of evidence that these principles had not been upheld historically in the area of urban land designation, the contemporary challenge prevailed. In the latter case, there could be no reliance on an overarching principle of liberal democracy within the traditional Chinese community, nor could allegations of racism buttress the argument for reform. Despite the economic power of the new arrivals, they were unable to dislodge the old guard at the CCC, nor initiate a reworking of the ideas and institutions of democracy.

Social relations are always reworked in the context of spatial relations and vice versa. Thus, although the contemporary changes that have occurred in Vancouver in the context of major economic and demographic upheaval may be broad, they will also always exhibit specific community outcomes that reflect the histories and memories of specific places and institutions.

Notes

Note 1: This testimony at the public hearing of October 5, 1992, is cited in Ley (1995).Back.

Note 2: Author's interview, November 1992. Owing to the ongoing sensitivity of this case I have used pseudonyms to protect the identities of those I interviewed.Back.

Note 3: See, for example, the article in Sing Tao Zhi Bao (Sing Tao Daily), May 26, 1977.Back.

Note 4: See, for example, the editorial in Da Han Gong Bao (Chinese Times), May 24, 1973.Back.

Note 5: Author's interview, July 1996.Back.

Note 6: Author's interview, July 1996.Back.

Note 7: Quoted in Alison Appelbe, "Elders Maintain Hold on Chinese Centre," Vancouver Courier, May 5, 1993, p.10.Back.

Note 8: Fred Mah, Chinese Cultural Centre Bulletin, March 30, p. 2.Back.

References

Duncan, Jim. 1994. "Shaughnessy Heights: The Protection of Privilege," in Neighborhood Organization and the Welfare State, edited by Shlomo Hasson and David Ley, pp. 58–82. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Fung, V. 1991. "Hong Kong Investment Funds Pour into Canada," Financial Post, June 17, p. 18.

Ley, David. 1995. "Between Europe and Asia: the Case of the Missing Sequoias," Ecumene 2: 185–210.

Macdonald, P. 1990. "Canada to Trim Numbers of Independent Class Visas," Hong Kong Standard, January 26.

Mitchell, Katharyne. 1993. "Multiculturalism, or the United Colors of Capitalism?" Antipode 25 no. 4:263—294.

—. 1994. "Zoning Controversies in Shaughnessy Heights," Canada and Hong Kong Update 11(Winter): 11.

—. 1997. "Fast Capital, Modernity, Race and the Monster House," Forthcoming in Burning Down the House: Recycling Domesticity, edited by Rosemary George. New York: Harper Collins.

Nash, Alan. 1992. "The Emigration of Business People and Professionals from Hong Kong," Canada and Hong Kong Update (Winter): 2–4.